Project Rapid Runway: Unraveling the Insidious Threads of Fast Fashion

The fast-fashion industry’s destructive and rapid capture of consumers

Rosie Kaur

December 5, 2023

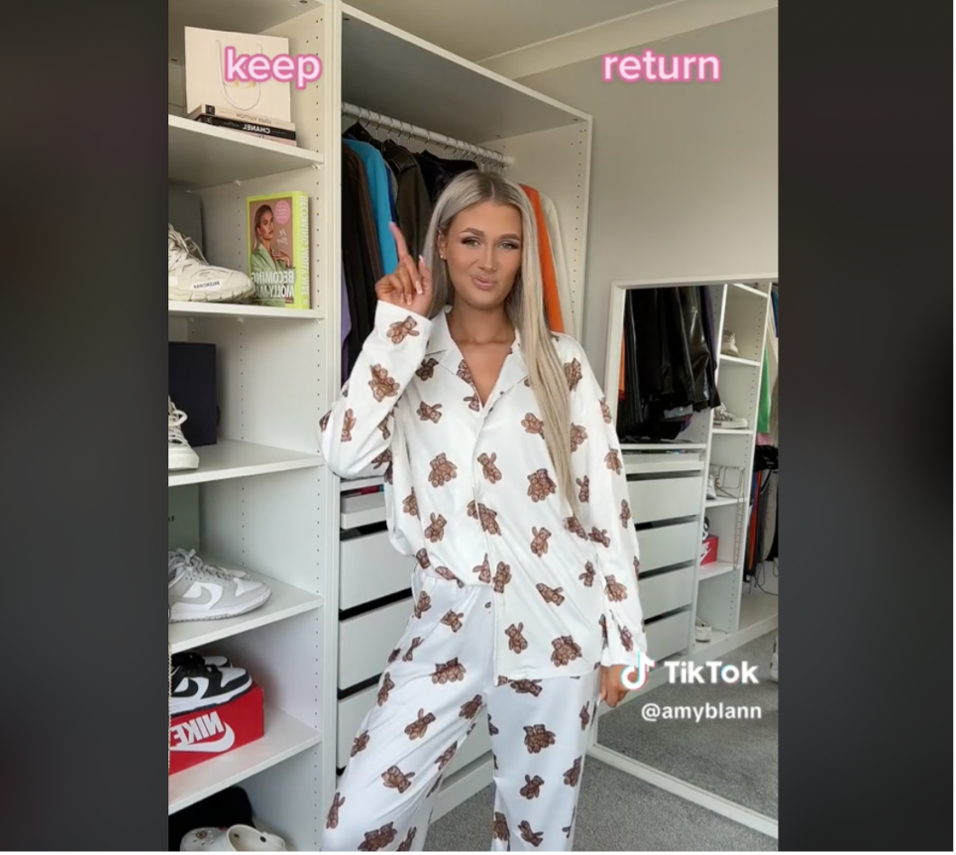

Lifestyle blogger Amy Blann, who promotes fashion and lifestyle tips, uploaded a reel on TikTok that showed several different outfits in a quick music clip that people could wear from Shein (“she-in”), a e-retailer from China.

Each product was accompanied by a price, which ranged from $5 to $10 per clothing piece. She captioned her reel: “keep or return” and brought her followers in by asking them to comment on their favorite outfit below. As a lifestyle influencer, she made the clothes look very appealing and proved to her audience that Shein is a brand to be trusted. She tagged Shein and made a quick and easy link for the outfits for followers to purchase. With 50,000 followers, she has quite the reach.

[Photo screenshotted from @amyblann’s Tik Tok account.]

The model of using social media influencers to market outfits has been incredibly successful for fast-fashion companies looking to sell a diverse array of clothing. In fact, Shein’s social media strategy has been so successful that it was among the most popular fashion brands in 2022. It was even given an award for using the most “efficient marketing tactics to boost brand awareness and loyalty”. According to the Times, Shein outdid Nike and Adidas as the most-Googled clothing brand.

Shein was founded in 2008 by Chris Xu, a U.S.-born entrepreneur and search engine optimization specialist. Shein went from being a low-cost Chinese clothing line to a global online-only fashion brand in only a matter of years. It went from making $10 billion in sales in 2020 to $100 billion in 2022.

Shein added between “2,000 and 10,000 individual [clothing] styles to its app each day between July and December of 2021.”

Similar to many other new online fast-fashion brands, Shein’s business model resembles that of Amazon – it is an online marketplace reaching over 150 countries and regions worldwide, relying on its 6,000 clothing factories in China and management software that collects real-time data on which items are selling in order to boost popular items. In fact, news articles such as the Guardian say Shein is even beating Amazon at its own game; according to an investigation by Rest of World, Shein added between “2,000 and 10,000 individual [clothing] styles to its app each day between July and December of 2021.”

Shein is so successful because it sells a large variety of cheap and “in-style” clothing that is delivered quickly. The company has built a narrative around what it means to be part of the fast-fashion industry – moving forward with the times, constantly challenging the status quo of fashion, and giving people affordable clothing. However, Shein and other fast-fashion brands propel the narrative that fast-fashion is a value add to society, all the while shoving the significant environmental and social damage that fast-fashion causes under the rug.

The Rise of Fast Fashion

Fast fashion is defined as inexpensive clothing produced rapidly by mass-market retailers in response to the latest trends. Through fast fashion, consumers are encouraged to purchase the newest styles on the market while they are “still hot,” and then discard of them after a few wears when they are no longer in style. The fast-fashion industry encourages a toxic system of overproduction and overconsumption, making the fashion industry one of the world’s largest polluters.

Some traditionally big players in the fast fashion industry include Zara and H&M, which started off as smaller shops in Europe around the 1950s. H&M is known to be the oldest fast-fashion giant, opening in 1947 and expanding to the states in 2000. Zara followed when it opened its first store in Northern Spain in 1975. The term ‘fast fashion’ first gained prominence when Zara arrived in New York in the early 1990s.. It was coined by the New York Times to describe Zara’s mission to take only 15 days for a garment to go from the design stage to being sold in stores.

Other traditionally big players include Uniqlo, Gap, TopShop, and Forever 21. With the growth of the digital age, a new form of fast fashion has come to being: ULTRA fast fashion, which take on similar business models to Shein. Apart from Shein, online stores such as Zaful, Boohoo, and Fashion Nova represent the new ultra-fast fashion brands. These online brands grew significantly during the 2020 pandemic lockdown and are particularly successful at using social media tactics and data analytics to increase their online sales.

With shirts on Shein being sold for $5-$10, and a recent Shein feature of 21,000 clothes under the “New in” section of the website, brands tempt consumers through cheap garments and a wide variety of new products. The efforts of fast-fashion brands certainly have been successful. According to a study conducted by McKinsey, the average person in the US buys 60% more clothing today than in 2000.

Social media capitalism, along with the profits that influencers and social media companies gain from promoting fast fashion, have fueled a market for even faster fashion than ever before. According to Casandra Ferrante (@fitforlaw), a law student and Instagram fitness and wellness influencer with 98,000 Instagram followers, there is significant pressure within the influencer community to produce a large volume of clothing content through brand partnerships. While this is how some people make a living, constantly producing content of clothing that entices people is also how influencers stay relevant and continue to get more traction and followers. This accelerated purchase cycle leads to fast, mass purchases and a glorification of overconsumption.

“There has been a shift…Instagram has become a platform for user generative content. That is how they are selling now. People aren’t watching television anymore. People are not going shopping anymore. Social media is used so often that it is easier to promote products through other people because that’s what people are watching. I don’t say ‘oh my god I want this dress because I was it on TV anymore.’ No, I saw somebody wearing this dress, so now I want to buy the dress. It’s like the Mean Girls line: I saw [this influencer] buying that, so now I am buying that,” says Cas.

“Ads are a thing, but I think 95% of advertisements now are through other people. I just have to post a video of me working out or studying for finals, and somebody will hit me up immediately after to ask me where I got my work out pants or my water bottle from.”

Photo taken captured by Aleska Servian, and found on @emerychijukan and @pheebstfashion Tik Tok accounts.

Ilaf Esuf, a 28-year-old fashion fanatic, noticed the desire among her community to purchase mass amounts of clothing increased significantly during the pandemic. An avid thrift shopper, she recalls feeling frustrated that she could no longer buy or trade clothes in stores during the pandemic. Shein used its data powers to figure this out immediately, and introduced itself to Ilaf via social media ads as a brand where you can try clothes on and return them without having to physically go to a store. She continued purchasing from Shein thereafter because the price points were so affordable, but eventually stopped and started thrifting again once she learned of how exploitative it is.

“It feels like [fast-fashion shopping] became easier because a lot of people had to shift to online sales and have deals that go along with that. People like me who didn’t previously shop online may be more comfortable with the concept now if they’ve had to do that during the pandemic.”

Although Ilaf stopped buying fast-fashion items, many people continued even after stores reopened. Fast-fashion clothing purchases increased by 46.3% during the first coronavirus lockdown. This staggering increase was driven by the tech industry, which sought to make a profit off individuals who were not able to leave their homes.

The harm caused by fast fashion

Fast fashion is harmful to the environment, workers, and consumers. The industry as a whole produces 92 million tonnes of textile waste annually and releases 10% of carbon emissions. It abuses, underpays, and endangers garment workers. Fast fashion manipulates consumers into excessive spending.

The demanding environment of the fast-fashion industry results in the wasteful use of natural resources, and the harmful use of chemicals that destroy the environment. Fast fashion textiles typically come from cotton, synthetic fibers and water. Cotton “is the most pesticide-dependent crop in the world, using 25% of the world’s insecticides.” Additionally, the textile mill industry in America alone produces 135 billion gallons of discharge water a year.

To make matters worse, fast fashion’s use of synthetic fiber, which requires the use of hazardous chemicals to prepare fabric, is particularly harmful. The chemical mixture with the water results in polluted groundwater, which causes significant health risks. The use of harmful chemicals also results in the exacerbation of issues such as biodiversity and soil quality.

In addition to the environmental cost, fast fashion exacts a human cost. Garment workers suffer through dangerous working conditions, low wages, and long hours. The consumption of fast fashion clothing in the United States and European countries disproportionately impacts workers in low and middle-income countries (LMICs), where garments are primarily manufactured. LMICs produce 90% of the world’s clothing, but occupational health and safety standards are not enforced there due to a poor political infrastructure and lack of enforcement mechanisms. As such, the reported health outcomes in LMICs include “debilitating and life-threatening conditions such as lung disease and cancer, damage to endocrine function, adverse reproductive and fetal outcomes, accidental injuries, overuse injuries and death.”

Furthermore, fast fashion has negative impacts on consumer mental health. Studies show that fast fashion triggers mental health conditions such as: psychological stress related to impulse buying and panic buying, feelings of insecurity, inadequacy, shame, guilt and anxiety in consumers, eating disorders, impulse disorders, shopping addiction, antisocial tendencies like theft and extreme debt in order to afford so many products, pathological hoarding, and climate anxiety.

As such, the reported health outcomes in LMICs include “debilitating and life-threatening conditions such as lung disease and cancer, damage to endocrine function, adverse reproductive and fetal outcomes, accidental injuries, overuse injuries and death.”

Fast fashion creates a culture where consumers constantly believe what they recently purchased is not good enough, and that they must shop more to keep up with the trends. With the proliferation of fast fashion through social media, consumers are never able to stop thinking about the next best thing to buy. Individuals simply need to open their Instagram, see an influencer posting new and trendy clothing and showing where they can purchase it, or see an ad for a $10 summer dress, to feel pressured into making a purchase.

Fitness influencer Ferrante notes that she personally has faced mental health challenges because of fast fashion, as both an influencer and a consumer. She calls the whole fast-fashion industry combined with social media to be “anxiety inducing.”

“I am very open about this too. Whether you are consuming or whether you are on the influencer side…it ruins people’s mental health. I do not think I have ever had such bad self-esteem or mental health until I worked in the influencing world. As an influencer, I do feel the pressure of always having to post, always having to try and get recognized, always having to try and be wearing and up to the trends.”

“I think there is pressure on both sides. There is pressure to be wearing and posting the most popular things, and then there is pressure to buy the most popular things. I can only imagine what it is like to be a lifestyle influencer and have a broader net, because just being in the fitness space is anxiety inducing.”

As an influencer, I do feel the pressure of always having to post, always having to try and get recognized, always having to try and be wearing and up to the trends.

Cas says that she is very transparent and candid with her followers about what she is buying and why she is buying it. However, most influencers are unfortunately not as intentional as she is. According to Cas, the harmful impact of fast fashion is typically not a conversation amongst influencers. Rather, influencers are always in such a rush trying to promote the next big thing that they do not even have the chance to think further about any of the harms of fast-fashion.

“[Conversations about the implications of fast-fashion] are never had. It is no questions asked. They are just like this person is buying it, let me buy it. I do not think there is any space because of how fast you have to act to get and post some of [these clothes], and how fast the items get to you.”

Influencers not only have to undergo the same challenges of feeling like they need to constantly be up to date on the latest trends, but they also feel the work pressure of a fast-paced environment. For example, Cas pointed to a time when she went “two weeks without posting because I needed a break from it,” and the “brand got upset.” “I was transparent that I am not going to post just to post, but a lot of people will not do that and will just post anyway.”

In order to continue making profit off of mass sales, fast-fashion brands expect their social media influencers to constantly pump out content for consumers to want to purchase. Without the work of influencers, their method of pressure through social media is not as successful.

Social media, however, is not the only way fast fashion reaches the mental health of individuals. Kirin Gupta, age 29, deleted her social media accounts years ago, yet the fast fashion industry has still managed to find her. She noted that Shein ads still self-populate when she is using Google, and multiple friends have suggested Shein as a resource for “easy event shopping” for events such as birthdays, bachelorette parties and weddings.

While she does not watch influencers on social media every day, she does experience what it means to be influenced in real life, which impacts her mental health all the same. According to Kirin Gupta, “fast fashion feeds another specific access of our capitalist desire to accumulate.” She says she watches those who she considers fashionable to accumulate “a solid amount of clothes at what seem to be very low prices, and often,” which increases her desire to make more purchases and bolsters the impression that “clothes are more disposable.”

“fast fashion feeds another specific access of our capitalist desire to accumulate.”

Mili Adhikari, a budding Instagram lifestyle and fashion influencer in her 20s, expresses similar concerns. “In the society we live in now, there is a lot of pressure to not re-wear clothes, which is supported by fast fashion. There is this idea of ‘why would I buy just one piece of clothing that I have to wear at different events, when I can buy five different fast-fashion items and wear something different to each event I am going to’. I think it makes people feel good be able to buy more clothes, because fast fashion usually mimics these high luxury brands, which makes people feel like they are in fashion…”