Much of this industrial activity is clustered around (and flows through) the Port of Corpus Christi. Opened in 1926, the Port initially served as a cotton export hub shipping agricultural products out of the naturally shallow Corpus Christi Bay. Following a dredging project in the 1960’s to allow access to larger vessels, most of the Port’s traffic centered around tankers bringing in crude oil to the nearby refineries located along the Inner Harbor. The Port was humming along—perhaps short of the dream of Elihu Ropes, an East Coast land speculator who had boasted that his 1890 proposal of a deep water port in Corpus Christi would turn the city into the “Chicago of the Southwest,” but respectable nonetheless.

The outlook for the Port of Corpus Christi would change drastically in the waning days of 2015. Decades prior, Congress had banned exports of crude oil in 1975 due to concerns emerging from the OPEC oil embargo. In December of 2015, the Republican-controlled House and Senate repealed this ban, turning forty years of American fossil fuel policy on its head.

The timing coincided with the shale oil boom, which played a key role in kick-starting a massive corporate lobbying campaign to build support for lifting the ban. Even House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi hailed the policy at the time as a “victory”, citing key environmental goals Democratic legislators voting in favor of the deal had secured.

All those broken records have led the Port of Corpus Christi to stand alone as the largest port for oil exports in the United States.

Regardless of whatever the movement to combat climate change may or may not have won from this deal, there were other clear winners. Among them was the Port of Corpus Christi, which set its sights on becoming the “Energy Port of the Americas” and has largely lived up to that moniker. The Port set new export records for crude oil every year for six years since the December 2015 decision to lift the ban, and is set to do the same in 2023. All those broken records have led the Port of Corpus Christi to stand alone as the largest port for oil exports in the United States.

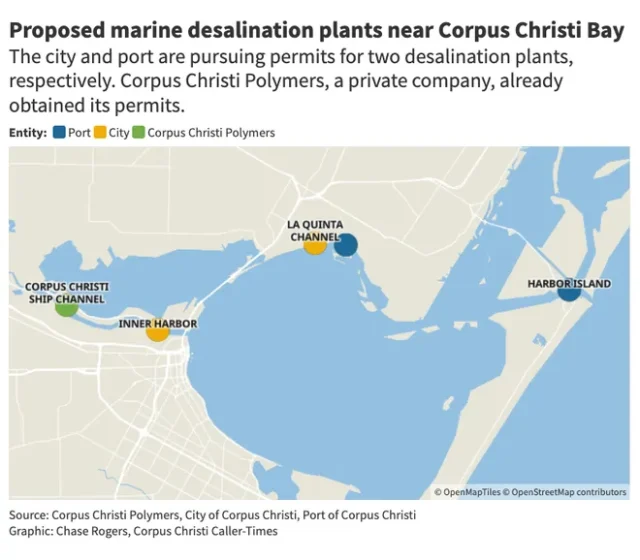

This growth would come with a cost. Many of the booming industries around the Port were deeply water-intensive, and needed reliable sources of freshwater. As a result, at the same time that the local water boil notices were drawing the attention of Coastal Bend residents, industry was setting its sights on water access as well.

By November of 2016, the repeated water boils of the past twelve months had put water security front-of-mind for understandably frustrated Corpus residents. The city manager’s resignation had come in the wake of the third water boil, five months before voters would decide whether to send incumbent Mayor Nelda Martinez back for a third two-year term. Martinez was a nine-year veteran of city politics who had previously served as an at-large city councilmember prior to her election as mayor in 2012. Despite winning reelection by more than 20 percentage points in 2014, by 2016 she had become, in the eyes of many voters, the face of bureaucratic ineptitude.

Clearly the system was broken, the establishment unable or unwilling to make the investments needed to provide basic civic services. In response, voters ousted Martinez in favor of “political outsider” Dan McQueen. McQueen’s election would not bring immediate water peace, however. As though to underscore the severity of the underlying problem, the Mayor McQueen era began with the water ban the day after he was sworn in.

This water issue was the most serious yet, caused by industrial contamination. While McQueen could hardly be blamed for a water ban so early in his tenure, his bid to shake up the halls of power would ultimately fall short for other reasons. Just thirty-seven days into his term—thirty-seven days marred by charges of falsified degrees, unpaid taxes, nepotism, and bizarre online rants—McQueen announced his resignation as Mayor of Corpus Christi via Facebook. A special election that May would bring in new Mayor Joe McComb, a political veteran and businessman. Yet despite the political theater of McQueen’s lightning-quick mayoral term, concerns over water remained at the forefront in Corpus Christi.

It was in this environment that the campaign to invest in water generation via seawater desalination first gained local prominence. Despite the fact that the water boils had been the result of failing infrastructure and industrial accidents, the conversation turned quickly to water availability. This topic change was no accident; time would show that it was largely a corporate bait-and-switch to secure water for industry.

From the Texas Tribune & Shalonn Simmons

Today, Corpus’ municipal water comes from four sources: nearby Lake Corpus Christi, the Choke Canyon reservoir system, the Colorado River, and Lake Texana, the latter two of which send their water south to Corpus via the Mary Rhodes pipeline. These four sources are then redirected by Corpus Christi Water (CCW) to nearly half a million citizens across seven counties.

Of course, not all of CCW’s water goes to individual use. In 2017, residential customers represented 36 percent of the raw water demand. But recent years, with the explosion of industrial investment following the repeal of the crude oil export ban, have seen industrial water needs soar as well. Some estimates place the current industry demand in the range of 60 to 80 percent of the total water supply, with the increase largely driven by a handful of massive new industrial projects.

As a result of these commitments, Corpus would use up the final thirteen years of its 50-year water supply plan virtually overnight. Over a decade’s worth of water, siphoned off by industry.

In many cases, these new projects were enticed to locate in the Coastal Bend via promises that the City of Corpus Christi would meet their water needs. Under Mayor McComb in 2018, the City promised six million gallons a day to Steel Dynamics, a steel plant. The year prior, they had assured ExxonMobil they would have ample water—twenty-five million gallons per day, at peak production—to build a plastics-producing facility. As a result of these commitments, Corpus would use up the final thirteen years of its 50-year water supply plan virtually overnight. Over a decade’s worth of water, siphoned off by industry.

Meanwhile, the City of Corpus Christi had been under prolonged drought advisories in 2015 before loosening the drought contingency plan in 2017. At the time, Mayor McComb stated that the old standards gave the impression that the city was water-poor. He pointed to the construction of the Exxon plant as evidence that this was a false belief.

“You can never have too much water, but we have enough now to attract development and keep our lawns and parks green,” McComb said.

Despite the looser drought standards, Corpus Christi has been under Stage 1 drought restrictions since June of 2022, and anticipates Stage 2 restrictions becoming necessary in December of 2023.

Residents found violating Stage 1 water use restrictions can face up to $500 in fines per day. During these restrictions, current Mayor Paulette Guajardo spoke publicly and urged her constituents to conserve water, stating that residents should “feel guilty” while brushing their teeth. While water conservation is certainly an important goal, citizens could be forgiven for feeling the advice rings hollow when industry up the road has a virtual free pass to use millions of gallons a day.

Despite Mayor McComb’s claims the city had enough water, the implicit belief by city officials was that their massive water promises required investments in water desalination as a new regional source of freshwater. McComb was an early advocate for desalination investments. Mayor Guajardo has continued to champion the cause. But as concerns and delays with desal mount, residents are understandably worried what might happen if these promises conflict with household water needs. Whose interests would the City prioritize: industry’s or citizens’?

For the Greater Good is a community group which formed in the wake of the water boil notices, determined to organize and force the city to address these issues which were disproportionately affecting the most vulnerable members of the community. Dr. Isabel Araiza, a professor at Del Mar College, was a co-founder of the group, which began by learning about city water infrastructure at the local library. There, they formed a small grassroots group studying the history of the region. The takeaway?

“Centering industry has always been a part of our city’s history, at least since the early 1900’s. Before that, it was ranching driving the city. But people’s needs have never been centered, it’s been industry that drives priorities and decisions,” says Dr. Araiza. Learning eventually morphed into action, and the group began attending city hall meetings to speak out and offer public comment.

“Centering industry has always been a part of our city’s history, at least since the early 1900’s. Before that, it was ranching driving the city. But people’s needs have never been centered, it’s been industry that drives priorities and decisions.”

The problem of Corpus’ municipal water supply was not only drawing attention locally. After the third water boil, in 2016, Dr. Araiza and For the Greater Good members attended a meeting hosted by “H2O Texas” at a downtown convention center. But during the talk, it became clear quickly that this group had not come to help out of the goodness of their heart. They were there to push desalination.

“They were saying we need a drought resistant water supply,” Dr. Araiza recalls. “But I remember looking at the graph they were showing and thinking, ‘Gosh, that population projection is actually pretty flat’”

Desalination (or “desal”) is the process by which water too high in salinity for human uses can be made potable. On average, seawater contains roughly seventy times the level of dissolved salts for water to be considered potable. Modern desal plants use a process called reverse osmosis to produce freshwater; while more efficient than the old “flash-distillation” method, reverse osmosis is still incredibly energy-intensive.

All those removed salts have to go somewhere: desal produces briny effluent as a waste product. A typical 42-to-58 freshwater-to-brine ratio means that effluent is actually the primary product by volume of reverse osmosis desalination. Generally, that wastewater is dumped back into the body of water it was drawn from.

Over time, the discharge of high-salinity effluent raises the surrounding water’s salinity. As the salinity increases, successive attempts to desalinate water from the intake body get progressively more difficult as the body of water approaches “peak salt.”

Today, desal provides much of the water needed for the arid nations of the Arabian Gulf. The prevalence of the practice had led the shallow, slow moving body of water to be about twenty-five percent saltier than normal seawater. As a result, the Arabian Gulf is one of the most adversely affected marine environments in the world, with discharge from desal contributing to the formation of massive dead zones and the loss of up to seventy percent of the Gulf’s coral reefs. Opponents to desal in the Coastal Bend worry that the technology will bring similar ecological ruin to their waters.

![[F]law School Episode 10: Mass Incarceration, Inc.](https://theflaw.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/RICHARDS_PHOTO_Protest2-640x427.png)