Repo Rise: Debt Collectors and Car Seizures

Corporate debt collectors are padding their pockets post-pandemic and leaving vulnerable consumers without their cars.

Brandon Lewis

August 13, 2023

In late July of 2022 in Brockton, MA, about 25 miles outside of Boston, MA, Kalonji Williams woke up in the middle of the night to the sound of two cars outside of his home. He immediately recognized the flashing lights of the tow truck. The second car was that of a Brockton Sheriff. And out of the third car emerged two men who appeared dressed as police officers. Initially, the man thought something had happened in a house nearby, but grew concerned when the tow truck reversed into his driveway toward his car. Mr. Williams bolted outside to confront the men. He quickly learned that the two uniformed men were not in fact police officers, but were instead constables- independent operators authorized by cities and towns to serve court papers and execute court orders- hired by a corporate debt collector to seize his vehicle. The constables informed Mr. Williams that a previous judgment against him for an old debt gave them the authority to seize his car as partial payment towards that old debt.

Weeks before, Mr. Williams received mail from a company he had never heard of and had never done business with demanding he pay upwards of $14,000 for an old debt from 2007. The only problem: Mr. Williams never acquired the debt and was unaware that a court had ordered him to pay. Mr. Williams informed both the Sheriff and the constables that there had to be a mistake and questioned their ability to seize his car. Ignoring his claims, the constable and the sheriff instructed the tow truck driver to proceed and within minutes the car was gone. As he stood in his empty driveway on that hot summer night, the shellshocked Mr. Williams wondered how and if he would get his car back, and worried about how difficult things would be in the coming days. Unfortunately for Kalonji, losing his car spawned a series of emotional and financial challenges that persisted for months. Talking through tears recently Mr. Williams shared, “Now I have this constant anxiety that I’ve never had before. And now I always fear that something else is going to go wrong. I fear that someone can just show up and take something that I’ve worked for and I have a right to.”

Today, soaring consumer debt puts more Americans at risk of car seizures, while credit card companies, auto dealers, debt buyers, lawyers, and the armed officials hired to execute the seizures make millions in the process.

As Americans rebuilt their lives in the wake of the pandemic, thousands have struggled to keep up with credit card and other payments. As a result, many have had their cars seized – often in the middle of the night with no warning. Today, soaring consumer debt puts more Americans at risk of car seizures, while credit card companies, auto dealers, debt buyers, lawyers, and the armed officials hired to execute the seizures make millions in the process. This piece explores how profit drives each of the those actors to do all they can to punish and leech off consumers; it will explain how state and federal debt collection laws fail to sufficiently protect the most vulnerable consumers from predatory debt collection practices including car seizure; and it will offer a critique of a debt collection system that values corporate profit at any cost; and finally it will briefly explore some of the interventions considered by policy makers at the state and federal level.

What’s the scale of the consumer debt market?

To put the scale of problem into context, consider some of these figures. First, consumer debt is at an all time high. The Federal Reserve Bank of New York reported in August of 2022, that consumer debt saw its largest increase since 2016 this year. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau reported in its 2022 annual report that credit card balances, auto loan balances, retail cards and non-housing debt grew to a new high of $4.33 trillion in the last quarter of 2021. Most of that debt was primarily driven by a $90 billion increase in credit card debt and a $80 billion increase in auto loan debt.

Narrowing in on credit card debt specifically, about 1 in 3 (more than 70 million) consumers have debt that is in collections. But what does collections have to do with car seizure?

I imagine most readers are familiar with the business model for credit card companies—lenders allow consumers to borrow money and repay them back over time—usually at a steep interest rate. That interest in some cases is the primary income stream for lenders. In 2016, American Express raked in $1.4 billion in interest income in one quarter. But when consumers stop payments, credit card companies can choose to 1) apply social and legal pressure to force the consumer to resume payments or 2) sell the remaining debt to another lender willing to apply pressure to consumers to resume payments (collections). Today, most credit card companies will sell delinquent debts to debt buyers for pennies on the dollar. For example, in recent years, Encore, the largest debt buyer in the country has purchased 2 to 3 million U.S. accounts per year and paid 8.6 cents on the dollar for each account. For a typical debt of $3,142, Encore paid $271.

To recoup on their investment, debt buyers like Encore must pursue debtors aggressively. A report into Encore in 2020 found that Encore was collecting tens of millions of dollars each year from debts it bought in 2009 or earlier. Selling and buying consumer debts is a profitable business model that encourages lenders and buyers to exert maximum pressure on consumers who have stopped making payments. Several decades ago, this practice was relatively uncommon. Today, debt buyers account for one-third of the total revenue in the debt collection industry ($4.22 billion).

In summary, Americans have enormous amounts of non-mortgage debt, and millions of Americans have fallen behind or stopped making payments on those debts. As a result, credit card companies and debt buyers have worked together to build a business/legal regime whose primary goal is to siphon as much money out of consumers as they can.

Outmatched and Unrepresented

As discussed above, debt collectors have a significant financial incentive to pursue consumers aggressively. Most often, that aggressive behavior begins in the courts where the rules advantage creditors and disadvantage consumers. One of the fundamental assumptions in the American court system is that courts are managed by neutral judges who hear arguments from lawyers and advocates on both sides of a dispute—an assumption that no longer fits the nature of litigation in debt collection.

30 years ago, it was common to see lawyers representing clients on both sides of a dispute. In a 2022 essay for Harvard Law Review, Daniel Wilf-Townsend noted that in the early 90s, 95% of lawsuits had lawyers representing both sides of a dispute, “[b]ut by 2013, that number had dropped to 45%.” Things are worse in debt collection suits. Between 2019 and 2020, less than 10 percent of defendants in debt collections were represented by an attorney. In the span of one generation our system of civil litigation became one in which most litigants were unrepresented. And it has caused disastrous outcomes for millions of consumers- particularly those facing debt collection.

“All [debt collectors] have attorneys, and attorneys are the primary drivers of debt collection.”, said Alexa Rosenbloom, a consumer protection attorney with decades of experience. At Harvard Law School, Attorney Rosenbloom works at the Harvard Legal Services Center in the Consumer Protection Clinic where she represents individual clients and supervises students interested in public interest work. Harvard Legal Services is one of few free legal services in Massachusetts that provides legal representation to consumers in debt collection cases.

Between 2019 and 2020, less than 10 percent of defendants in debt collections were represented by an attorney.

Attorney Rosenbloom has defended countless consumers facing debt collection and knows the perils of attempting to navigate our legal system without legal representation. Most consumers don’t have representation and most consumers don’t show up for their court date – typically because they haven’t been informed about it. Wilf-Townsend noted in his essay for the Harvard Law Review that one study found that 71% of consumers who had been sued by a debt buyer never received notice about the legal proceedings against them.

When defendants are absent, a fact debt-collectors and their attorney’s count on, they are typically issued default-judgments. Judges issue default judgments to plaintiffs typically when the defendant fails to respond or fails to appear in court. Estimates from the Federal Trade Commission in 2010 speculated that between 60% and 95% of debt collection lawsuits result in a default judgment against the plaintiff. Attorney Rosenbloom verified these findings based on her own experience saying, “[Plaintiff’s attorneys] get a lot through default judgments. It’s almost like a mill-like process where they can process hundreds of cases in a short amount of time and get enormous default judgments.”

It’s worth noting that most consumers are hauled into court on debt collections for relatively small amounts of money, but money that they nonetheless cannot afford to pay. A survey from the Federal Trade Commission found that “of 90 million consumer accounts purchased by debt buyers, for instance, indicated an average face value of around $1600.”

Once a consumer has a default judgment entered against them, the debt begins to accrue interest. In Massachusetts, a state broadly considered friendly to consumers, the interest rate for judgments is 12%. 12% interest is significant and can cause a default judgment to balloon into a debt consumers can never hope to pay.

All of these factors came to play in Mr. Williams case. He was never given notice of the original law suit against him for a credit card debt he never accrued. Because he didn’t have notice, he didn’t show up to court in 2008 and a default judgment was entered against him for the debt which at the time was less than $2,400. All of this happened without Mr. Williams knowledge in a courtroom where only the debt buyer had representation. That initial judgment sat and collected interest for 14 years while the debt bounced between different debt buyers. By the time the tow truck pulled into Mr. Williams yard in July of 2022, the default judgment had collected almost $12,000 in interest ballooning to more than $14,000. Mr. Williams serves as just one example of how a court system that has become routinized and co-opted by corporate plaintiffs’ results in life altering damage for consumers.

Attorney Rosenbloom reflected on how consumers get steam rolled in consumer debt cases and the ripple effects it can have on their lives—particularly once their cars are seized in connection with a debt. “People are incredibly reliant on their cars, so [debt collectors] see it as a very powerful coercive lever.”, she recalled. She talked briefly about a new client whose car had been seized and the impact of that seizure on her relationship with her young daughter. “Her daughter had to walk to school long-distance in the cold for multiple days… imagine the shame of having to explain to a young child what’s happening.” she said of her client.

Exploiting the Pandemic for Profit

Debt collectors were aggressive in their debt collection practices prior to the pandemic. State laws allowed debt collectors to seize family homes and cars, garnish wages, or empty a bank account. Kari’s Fiotti’s medical debt was put in collections in 2013 following a fall which broke her wrist. When she failed to show up in court after being sued by a debt buyer, the debt buyer seized her bank account because she didn’t have enough funds to cover the debt. Kari was forced to overdraft her account to cover her groceries and eventually had to hire a lawyer to help her negotiate with the debt buyer. Kevin Evans had his wages garnished by his lender Capital One also in 2013. Twice each month, Capitol One would take 25% of his paycheck. At the time, NPR and ProPublica found that one in ten working Americans between ages 35 and 44 were getting their wages garnished.

In Massachusetts, constables were known to charge debtors as much as $900 during a car seizure for their role in assisting and accompanying the tow truck.

Car seizures were also a part of the pre-pandemic landscape. In Massachusetts, constables were known to charge debtors as much as $900 during a car seizure for their role in assisting and accompanying the tow truck. When debtors could not raise the funds to cover the fees and the outstanding debt, their cars were typically sold at auction. In Massachusetts, constables received a portion of the proceeds from these car sales giving constables a perverse incentive to quickly seize cars and charge debtors high fees. However, profits were ultimately bounded by the demand for used cars. Used cars just weren’t that profitable before the pandemic. But changes in the global supply chain and consumer demand led to a surge in used car prices.

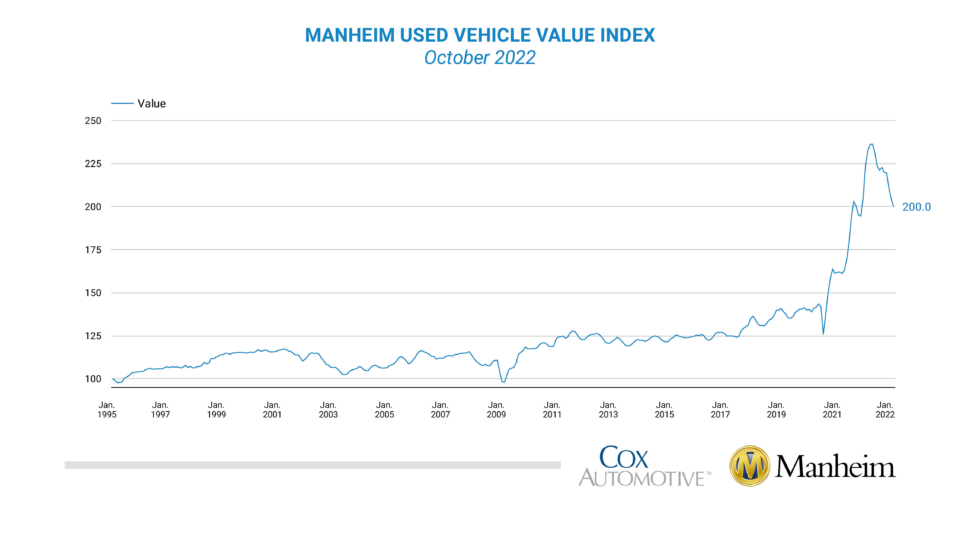

Chart of used car values from 1995- 2022 from Manheim

In late 2021, as seen in Figure A, some used car prices surged by almost 50% when compared to their value in 2020. Debt buyers observing the used car market quickly noticed that they could exploit this opportunity. If used car prices were up and consumer debt was up, debt buyers could leverage valuable cars to pad their pockets. And that’s what they did. Barron’s reported an 11% increase in car repossessions for borrowers with lower credit scores and a nearly 4% increase in car repossession for borrowers with higher credit scores.

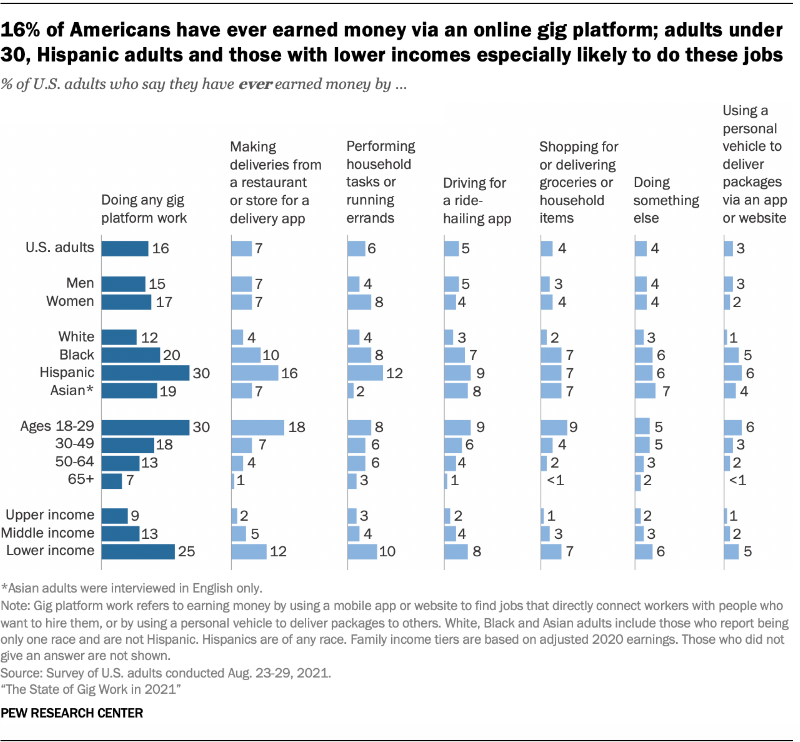

For most workers, especially those in cities without reliable, accessible public transportation, a car is essential for daily life. First, consumers need cars to get to work – particularly low wage or hourly employees who don’t have the luxury of a job that allows them to work from home. Dependence on cars increased for some workers who lived in cities or states that curtailed public transit during the height of the pandemic. Workers in D.C. saw 15 rail stations close in March of 2020 that did not open until later that summer. Without a car, many consumers – including front line workers – could be put on a path that leads to job loss, a cascade of unpaid utility bills, deferred medical care, unpaid rent, and eviction or foreclosure. And increasingly in the gig economy, workers don’t need cars just to get to work, they need cars to do their work. A 2021 Pew Research report found that 16% of Americans had worked or are working in the gig economy. Figure B below from that report shows that many of those gig workers rely on their cars for work. Gig workers pick up people’s food, or make their living driving Uber or Lyft. Cars are fundamental to many consumers livelihoods.’

Graph from Pew Research Center on percentage of American workers making money in gig economy

Allowing a creditor to seize a car can have wide ramifications, hurting the consumer and fraying the consumer’s relationships with employers, friends, family, utility providers, or other creditors.

Mr. Williams explains how the loss of his car led to a downward spiral. Immediately, he was riddled with anxiety and worry. He struggled to sleep. He emptied his savings account and offered it as a down payment on the debt. The creditor accepted the payment, but forced the Mr. Williams to commit to future payments of nearly $200 per month. During the days he was without a car he sank further into debt to cover the cost of a rental car. He fell behind on his utility bills and his mortgage and had to ask a family member to help him. He missed almost four days of work, compounding the stress caused by the car seizure.

Allowing a creditor to seize a car can have wide ramifications, hurting the consumer and fraying the consumer’s relationships with employers, friends, family, utility providers, or other creditors.

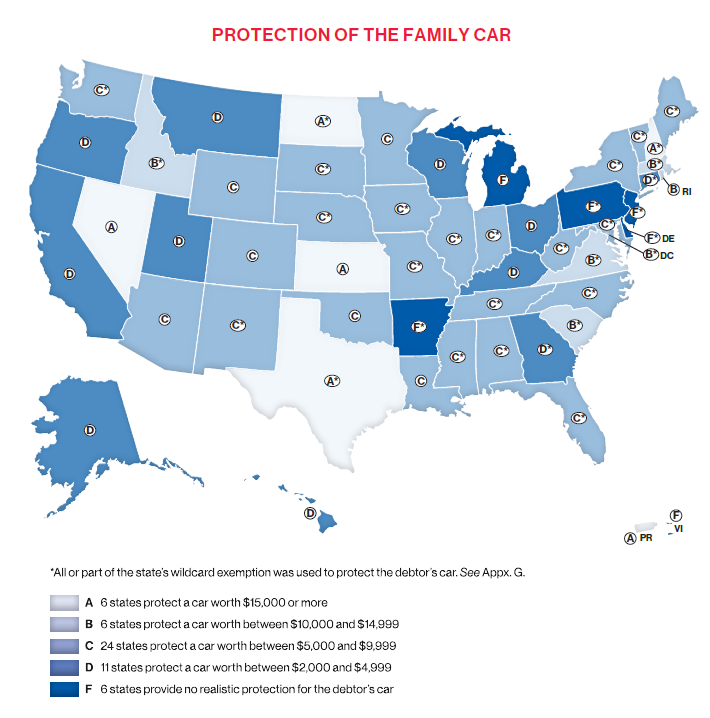

Though used car prices have cooled, the average retail price for a used vehicle in most states sits well above $20,000. As depicted in Figure C below, no state provides protection from debt collectors for family cars worth more than $15,000 which means that consumers with debt in every state are vulnerable to car seizures.

Map from the National Consumer Law Center on how states do or don’t protect family car from debt collection seizure.

In February 2020, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, the federal regulator charged with monitoring the debt collection industry, issued a warning to debt collectors. The CFPB’s guidance outlined steps the agency would take to protect consumers from illegal car repossession. The CFPB has warned that it will closely review repossession practices by loan servicers who might be eager to cash in on the used car bubble.

Beyond monitoring, the issues explored here suggest elucidate fundamental structural problems with our current approach to resolving debt collection. A few corporate actors now dominate and clog state court systems with routine, low-dollar debt collection cases where defendants are often absent and unrepresented. In his work, Wilf-Townsend found that in 2019, just ten companies were responsible for nearly a fifth of all civil filings in 19 different jurisdictions. Ten corporations responsible for nearly one in five state civil cases – typically debt collection – should be a cause for alarm in state courts, state legislators and with federal regulators. These corporate actors have a record of fraud and abuse against consumers – many never even inform consumers of the ongoing litigation against them- but are still allowed to participate in our court system, acquire judgments, and seize cars and other personal property to collect on those debts.

Courts and regulators have done little to curb bad practices by corporate actors, and consumers suffer as a result. Corporate debt collectors and their lawyers control almost every aspect of the debt collection process, and courts personnel do little to challenge their evidence, procedures, or practices. Armed with court judgments, corporate debt collectors are given almost unchecked authority to enforce their judgments through wage garnishment, property liens, emptying bank accounts, and property seizure—extracting wealth from vulnerable communities for the sake of corporate profits.

Some state leaders have begun to speak out more forcefully against abusive debt collection practices like debt seizures and worked with advocates to pass laws and regulations protecting consumers. New York’s Consumer Credit Fairness Act of 2021 officially went into effect in May of 2022. The act is intended to have an impact on debt collection lawsuits filed by creditors or debt collectors. The act shortens the statute of limitations giving debt collectors less time to bring their suits, and the act imposes more stringent notice requirements in an effort to make sure more defendants are aware of the legal proceedings against them. Newly elected Massachusetts Governor Maura Healy secured a $12 Million settlement against the country’s largest debt collector Encore in 2022 in her capacity as Attorney General. And in 2021, Connecticut Governor Ned Lamont signed a bill into law which raised the value of cars that are exempt from debt collectors.

These efforts, though important improvements, fail to address the structural forces that keep consumers and their cars at risk. Corporate debt collectors will continue maintain access to expensive legal representation. Consumers will likely remain unrepresented and unaware of the complicated legal proceedings in debt collection suits. Now is the time for our political leaders to take bold action and reimagine how our system could be reshaped to better protect consumers and their property.