When I was investigating payday loan complaints as an investigator at Montana’s Office of Consumer Protection, I quickly discovered a curious phenomenon: many of these payday lenders were associated with Native American tribes. A familiar pattern began to emerge.

Montanans would complain to the Office of Consumer Protection when they sensed something was off with their short-term loan. As former Montana Consumer Protection Investigator Marcus Meyer explains, “They had made the payments and paid back what the original loan was for and then some, and just were not seeing any sort of light at the end of the tunnel as far as getting it paid off.”

Even though they had been faithful with payments, the principal on the loan never seemed to shrink. This was because borrowers often believe their payments are going towards their principal, when in fact they are covering loan renewal or interest charges.

It’s easy to become confused about where your bi-weekly payments are going. That’s why one of the goals of the Montana Consumer Protection Office is to help consumers get information about their loan and where their payments are being distributed. “We would essentially try to work with the payday loan company to write off the remaining balance of the loan,” Marcus said.

Adding to consumers’ confusion about their payday loan was the fact that most believed they’d discovered these arrangements to be illegal. Montana has a law capping interest rates at 36%, which was approved via ballot measure at the height of the late 2000s payday lending crisis. Consumers who found out about this statute assumed that the payday lending company they used had broken the law by selling them a loan product with interest rates far beyond 36%.

Unfortunately, that doesn’t mean Montana can always enforce their law to stop payday lending, especially when the loan transaction was conducted over the internet. Most often, when Marcus sent a consumer complaint to a payday lending company, he would get a letter back – not from the lender, but from a tribe.

The body of the letter would be a legal disclosure, explaining in pleasant but firm language that he was not dealing with a regular lender, but a sovereign nation. An example is available on the website for Montana’s own Plain Green, LLC, which has in the fine print of their website footer a similar disclosure:

Plain Green, LLC, is a wholly owned company of the Chippewa Cree Tribe of Rocky Boy’s Reservation, Montana; A Native American Tribe federally recognized by the government of the United States of America, and we operate within the boundaries of the reservation. By entering into an agreement with Plain Green, you are availing yourself upon the jurisdiction of the Tribe and fully understand and consent that any agreement entered into is governed by all applicable federal law and the laws and lending codes enacted by the Tribe’s Federally recognized sovereign government.

The point of this disclosure is to highlight that there are separate laws governing the Chippewa Cree Tribe and American states. The federal government recognizes the Chippewa Cree Tribe and 573 other tribes as sovereign, self-governing nations. And Plain Green is right that state regulators have very little power to compel other sovereign nations to follow their domestic laws.

In my experience processing Montana’s consumer complaints, these rigorous legal disclosures would often be followed by a brief note, stating that even though the company had every right to pursue the consumer for the full amount of their outstanding obligation, they were writing off the balance of their account. Investigators recorded the write-offs as “good faith adjustments,” notified the relieved consumers, and closed the files.

It was a tenuous quid pro quo, but the Consumer Protection Office was happy to save Montanans some money and credit consequences, while the company was happy to avoid further attention. Witnessing this strange pattern between the Consumer Protection Office, payday lenders, and Native American tribes made me curious. How did tribes get wrapped up in the schemes of high-interest lenders?

The story of corporate-tribal collaboration on payday lending begins in the 2000s. Even before their agreements with tribes, payday lenders had become visibly profitable and publicly despised over their exploitation of the working poor and connections to bankruptcy.

The 1990s had been a period of mass deregulation, with the Supreme Court’s decision in Marquette vs. First of Omaha triggering a nationwide rollback of state usury caps. As states removed these lending caps, they created the environment for high-interest lenders to thrive.

By 2008, payday lending storefronts nationwide outnumbered McDonald’s and Starbucks storefronts combined. Scholars, politicians, and community leaders began to take notice and raise awareness about the harms of payday lending.

Lenders then spent millions lobbying Congress to protect the then $42-billion-per-year industry, ultimately staving off sweeping federal intervention. However, states again began passing highly popular lending caps to rein in exorbitant rates at the local level.

These new state lending laws were a big problem for payday lenders, whose business models would fail if they reduced their interest rates to compliance levels. High-interest lenders instead started looking for ways to avoid the new laws altogether, with the help of the quickly growing internet. Soon, these corporations saw potential in the sovereign immunity of Native American tribes to shield them from state lending laws.

Sovereign immunity is the freedom from lawsuits which Native American tribes enjoy by virtue of their status as domestic dependent nations. Unless the tribe waives their immunity, or Congress takes that immunity away, tribes cannot be sued by States or individuals.

The sovereign immunity doctrine is one of the few surviving pro-tribe tenets of federal American Indian law, and it has been zealously guarded by courts and Congress at crucial points in its development. The doctrine is essential to tribes because without it, tribal governments could not control which laws applied on reservations – an essential part of national self-determination.

Payday lenders saw tribal sovereign immunity as a shield behind which they could hide.

Payday lenders saw tribal sovereign immunity as a shield behind which they could hide. If they could strike a deal with tribes to bring their payday lending business under the authority of the tribe, tribal sovereign immunity could protect their business’s actions from being subject to state laws. If a borrower were to complain that they were violating a state’s lending laws, the lenders could say, “You actually can’t touch us because we’re an arm of this tribe, which has sovereign immunity.”

With the combination of tribal sovereignty and the internet, lenders could find customers in states where their rates were illegal, but then claim immunity from many of that state’s regulations. In return for tribes’ sovereignty, lenders promised to share their revenues, employ tribal members, and boost economic growth for reservations.

By the mid-2000s, dozens of tribes had signed these “rent-a-tribe” agreements with payday lenders. Profits for payday lenders continued to soar, with the white CEOs of tribally affiliated lending companies leading lavish, ostentatious lifestyles in the public eye. Ideally, the tribal lending model’s success should have employed tribal citizens, boosted economic development, and stimulated the tribes’ economies through the distribution of new revenue to tribal members. However, the reality for tribes was very different.

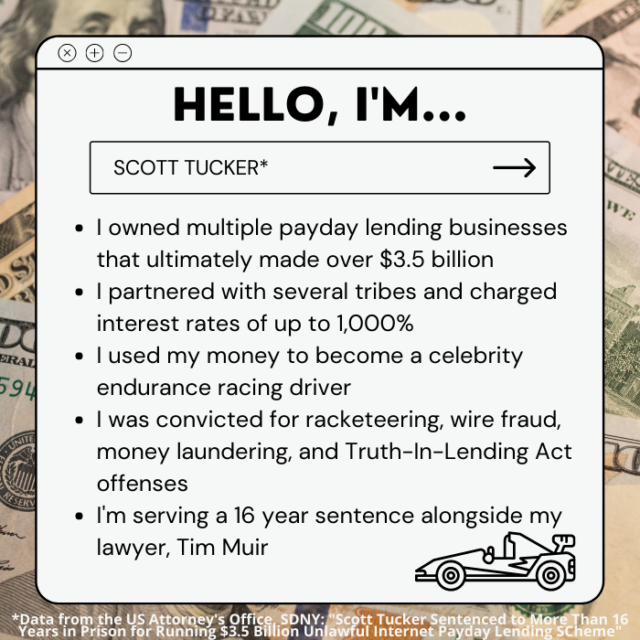

These arrangements maximized financial and legal risk for the tribes while minimizing their ownership and management of the often lucrative lending operation. Despite promises of employment, the lending corporations would go on to hire minimal tribal staff. Call centers for the payday lending operations weren’t housed on reservations – even though call center employees report that they were trained to answer questions about their location as though they were on the reservation of their tribal partner. Tribes on average received only 1-2% of payday lending revenues made possible by the exploitation of their sovereign immunity. For example, former payday lending giant Ameriloan paid their partner, the Miami tribe of Oklahoma, only one percent of their revenues while simultaneously bankrolling the auto-racing team of their CEO Scott Tucker.

Tribes were grifted by payday lending corporations in a very similar way to consumers. In their negotiations with both desperate consumers and struggling tribes, corporations held a position of power and influence through the promise of much-needed cash.

In their negotiations with both desperate consumers and struggling tribes, corporations held a position of power and influence through the promise of much-needed cash.

Many reservations urgently need economic opportunity, particularly those who do not benefit from proximity to urban centers or abundant natural resources. As University of Connecticut School of Law professor and American Indian Law specialist Bethany Berger remarks, “Poverty is super high on reservations, unemployment is super high, and tribes have been cut off from a lot of the things that they could use to rebuild their economies.”

Extremely high unemployment, ranging from 20 to 80 percent on Indian reservations in the US, undermines the functionality of tribal economies and makes it more difficult for tribal members to make money, spend money, house themselves, and pay for education.

Sources: Northwestern University, “What Drives Native American Poverty?” February 2020; Penn Program on Regulation, “Establishing Economies on Indian Reservations,” April 2021.

While it may be tempting to turn up a nose at tribes who decided to facilitate payday loans, it’s helpful to remember that Professor Berger’s reflection on economic development doesn’t only apply to tribes. Many poorer nations engage in similar behavior when economic situations are dire.

The Cayman Islands, The Republic of Seychelles, and Panama are hubs for offshore banking meant to help the wealthy evade their tax responsibilities. The Bahamas, Cameroon, and Sierra Leone offer flags of convenience to ocean vessels, providing legitimacy and regulatory shelter to many illegal fishing and smuggling vessels. Haiti, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Mauritania are known to be the best places to launder money. Around the world, we see that struggling nations can become shelters for undesirable corporations and activities when there is the promise of much-needed cash. Corporations can then seize upon these less-regulated environments to house their exploitative schemes.

Eventually, the tribal-corporate lending partnership began drawing negative attention. The Department of Justice started investigating online payday lenders in 2013, around the same time that the New York State Department sent cease-and-desist letters to 11 tribally owned online lenders. State Banking Departments began fining lenders for making loans that violated their state laws. Then, penalties moved from the civil to the criminal. In 2016, Scott Tucker and his attorney Timothy Muir were convicted on federal racketeering charges related to Ameriloan and its ownership arrangements with the Miami, Modoc, and Santee Sioux tribes. Tucker and Muir were ultimately sentenced to over 16 years in prison time.

Source: United States Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of New York: “Scott Tucker Sentenced To More Than 16 Years In Prison For Running $3.5 Billion Unlawful Internet Payday Lending Enterprise”

As heightened regulatory scrutiny seemed to foreclose the future of tribal lending, some corporations moved to maximize profit and externalize the costs of potential business failure. At least one company, American Web Loan, looked for a final favor from their partner tribe. The company’s owner, Mark Curry, convinced the Otoe-Missouria tribe to purchase American Web Loan for $200 million. The Otoe-Missouria couldn’t afford to purchase the business, but Curry financed the sale himself, charging 10% interest on $95 million of the purchase and getting the rest through a five-year non-terminable consulting deal. After approving the deal, the Otoe-Missouria tribe had to pay $4 million to Curry per month for five years. As a result of the arrangement, American Web Loan truly did belong to the tribe, but so did a host of extreme financial obligations to the CEO they had helped make rich.

Payday lending isn’t the only area where corporations have sought to exploit tribal sovereign immunity. The Supreme Court recently denied certiorari to the Saint Regis Mohawk Tribe and Allergan after lower courts ruled that tribal sovereign immunity couldn’t shield Allergan’s patents from the Patent Trial and Appeal Board’s review. Allergan had been looking for a way to protect its patent for the popular dry eye drug Restasis, after other drug companies sought the right to sell generic versions. Allergan transferred their patents for Restasis to the Saint Regis Mohawk Tribe in a naked bid to hide them from the patent court. In return, the tribe would charge regular payments to license the patents back to Allergan, who could continue producing their drug.

When corporate actors use tribal sovereign immunity to do unsavory things like evade consumer protection laws or block affordable medication from entering the market, they risk provoking legislators to react by challenging the doctrine itself.

Ultimately, the Allergan tribal immunity scheme failed. Although both Allergan and the Saint Regis Mohawk Tribe tried to defend their patent arrangement, it was rejected by the patent appeals board. They went on to lose in the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit as well. When the tribe defended their agreement with Allergan, they cited the importance of economic opportunity for the tribe, asking critics to consider the community’s “chronically unmet needs.”

These calamitous corporate partnerships can have backlash effects for tribes and for the fidelity of tribal sovereign immunity law. When corporate actors use tribal sovereign immunity to do unsavory things like evade consumer protection laws or block affordable medication from entering the market, they risk provoking legislators to react by challenging the doctrine itself.

Even though tribes are considered sovereign nations, their complicated colonial history with the US has, in a way, watered down their sovereignty. Tribes are not treated as truly independent nations, like France or Spain, but as “domestic dependent nations” whose status is subject to the whims of Congress.

Congress has an ability called “plenary power” over these tribal nations, which means it has absolute authority to make any decision about tribes that it likes. This means that Congress also has the power to curtail or even eliminate tribal sovereign immunity. “Congress has plenary power to do whatever the heck it wants with respect to tribal sovereignty and sovereign immunity,” Professor Berger states. “And there have been multiple bills trying to limit tribal sovereign immunity … because of this payday lending situation as well.”

Rather than crafting laws to punish corporations for their greed and exploitation, members of Congress have targeted tribes as the “bad guys” in several of these sovereign immunity schemes. When the tribal lending crisis was center stage, Oregon Senator Jeff Merkley introduced a measure that would require tribes to use the laws of the lender’s state rather than the borrower to govern their loan.

After the Allergan tribal immunity deal, Senator Tom Cotton of Arkansas introduced a bill called the Preserving Access to Cost Effective Drugs (PACED) Act. The core of the Act is reaffirming the Patent and Trade Office’s ability to “review patents regardless of sovereign immunity claims made as part of sham transactions.” Bills like these seem benign because they purport to protect people from corporate exploitation, but because the fixes are aimed at tribes and not corporations, they threaten to slowly chip away at the doctrine of tribal sovereign immunity.

Tribal sovereignty is really about the tribe’s right to govern their own people, preserve their indigenous culture and language, and live according to their own laws and customs.

Congress isn’t the only threat to the tribal sovereign immunity doctrine. When legislators and the public rethink tribal sovereign immunity, it’s always possible that the Supreme Court will do so as well. The Second Circuit recently held in Gingras v. Think Finance that injunctive suits (lawsuits that seek relief in the form of prohibiting or mandating an action rather than handing over a sum of money) against tribal affiliates can be permitted in some circumstances. If this interpretation of Supreme Court precedent is adopted by other circuits, injunctive suits against tribes could proliferate, spelling a serious change in how the tribal sovereign immunity doctrine has been applied historically.

Immunity from suit – and the sovereignty that it protects – is crucial for tribal self-determination. Tribal sovereignty is really about the tribe’s right to govern their own people, preserve their indigenous culture and language, and live according to their own laws and customs. It is especially important because each of the hundreds of recognized tribes in the United States has its own unique customs, history, and circumstances. The reduction of tribal sovereignty in favor of a uniform federal American Indian policy would be a huge loss, since it could never reflect the diverse needs and desires of so many different people groups.

Native American people also prioritize their own sovereignty when they mobilize publicly. In his book on Indigenous environmental resistance to mining projects, University of Delaware professor Saleem Ali writes that “Ultimately, tribes decide whether to go ahead with a mining project or to resist it on environmental grounds based on which of these two options is a greater threat to their sense of sovereignty.”

While corporations have profited greatly off “rent-a-tribe” schemes, tribes have received marginal benefit and suffered heightened public scrutiny around the use of their sovereign immunity. Despite the clear exploitation of tribes by corporations seeking regulatory shelters, conversations around economic development on reservations often place blame on Native American communities for not doing more to “attract private development.” When asked, Native American people provide very different reasons for persistent reservation poverty, including:

- A lack of access to financial capital

- Lack of education, skills, and technical experience, and the means to develop it

- Reservations lack control over their own natural resources

- Reservations are disadvantaged by distance from markets and high costs of transportation

- Tribes can’t compete with non-Indian communities to bring investment to their communities

- Federal, state and local politicians are inept, corrupt, or uninterested

One suggestion for boosting development on reservations is to increase the number of Indian-owned businesses.

Financial and educational support for Native American entrepreneurs should be at the forefront of the Biden Administration’s agenda. The Administration’s budget for fiscal year 2023 includes $4.5 billion for Indian Affairs programs, a $1 billion increase over 2022. However, rather than economic development and opportunity, the priority of Biden’s budget is public safety. The budget includes $562.1 million for policing, detention, and Tribal courts. The amount allocated to Community and Economic Development is only $72.3 million.

Tribal sovereign immunity is essential to tribes because it is powerful. Its power is what attracts wealthy corporations who are eager to expand shareholder profits by limiting the amount of regulation to which they are subject. Unfortunately, tribes have been placed in too vulnerable a position to be expected to understand, avoid, and repel such offers from crafty corporations.

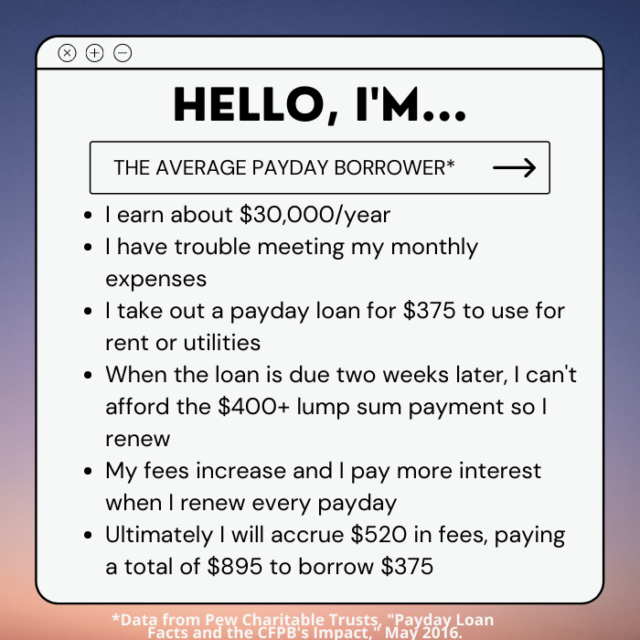

Similarly, consumers caught in the paycheck-to-paycheck cycle – often by their corporate employer – are also disadvantaged when deciding whether to take out a payday loan. Their urgency enhances the bargaining power of corporations, who can charge exorbitant rates and fees to a virtually captive audience. For both tribes and low-wealth consumers, corporations abuse vulnerable actors’ financial desperation, conning them into accepting long-term detriments in exchange for badly needed short-term rewards.

Though the number of tribal lenders has dwindled, it appears that tribal payday lending will persist. Several circuits have developed “arm of the tribe” tests for determining whether for-profit commercial entities are legitimately controlled by the tribe and can therefore use tribal sovereign immunity.

The Supreme Court has not yet ruled on a definitive test, so these standards are currently circuit-specific. In Breakthrough Management Group, Inc. v. Chukchansi Gold Casino & Resort, the Fourth Circuit solidified their own test, which mandates their courts consider the method of the lending entity’s creation, their purpose, their structure, ownership and management, the tribe’s intent to share its immunity, the financial relationship between the tribes and other entities, and the policies underlying tribal sovereign immunity.

In a significant win for tribal lending, the Otoe-Missouria tribe recently passed the Fourth Circuit’s test and legitimized the lending operations of their two lending companies, Great Plains and Clear Creek Lending. Following the same test, a Florida court threw out a case against the Tunica-Biloxi tribe last month, granting their payday lender partner Mobiloans sovereign immunity despite data showing they had paid only 2% of revenues to the tribe in 2018.

The judge in the Tunica-Biloxi case mentions wanting to protect sovereign immunity for Mobiloans because a loss for the corporation would hurt the struggling tribe’s ability to support its needs. Similarly, the sudden elimination of payday lending altogether, without providing another option for consumers in need of short-term credit options, may also devastate great swaths of the working poor. Until we address the root causes of poverty and get reservations the support they deserve, corporations are likely to continue to prey on low-wealth people, both Native and non-Native.