Harvard’s dormitories captured by Somesh Kesarla Suresh.

This discussion on citizens and leadership belies the actual mission of Harvard which is to maintain the most potent brand in higher education. Alongside this goal, the University shepherds the largest endowment in the world at $53.2 billion. If Harvard were a nation, its endowment would put it as the 82nd richest nation on the planet, out of 190. Harvard would sit just below the gambling capital of the world, Macao, and Uzbekistan. Where Uzbekistan’s GDP grew 5.3% last year, Harvard’s investments returned a staggering 33.6% in the 2021 fiscal year.

Harvard made brilliant bets during COVID-19 and managed to save hundreds of millions in operating budget by becoming the most expensive online school in the world. While the rest of the world was struggling to recuperate in 2021, Harvard made $11 billion. With this monstrous windfall, the University did not ensure that its staff was paid or lower tuition. Instead, it attempted to fire all contract employees during the onset of the pandemic in 2020 and, during its 33.6% endowment increase year of 2021, it attempted to slash 20% of its dining employees. Citing the “continued financial pressure” of the pandemic, even though all students were back on campus and Harvard’s revenue was exploding, it also decreased the available hours of its staff by 8%.

If Harvard were a nation, its endowment would put it as the 82nd richest nation on the planet

That covers how Harvard treated its staff during 2021, but the students must have been given concessions on tuition. Students were sent away from campus in the spring of 2020 and were not allowed to return until the fall of 2021. Abraham Barkhordar, a Harvard Law student, sued the University in a class action suit claiming that Harvard’s charging full tuition for remote learning was a breach of contract. U.S. District Judge Indira Talwani dismissed the students’ claim because “they had failed to show that Harvard had contractually promised they would receive in-person instruction and access to on-campus facilities during the spring 2020 semester.”

This reasoning feels sound. If I were to buy a ticket to see U2 at Fenway Park, I would be jazzed. If Bono were to get the sniffles and the Edge were to jam a finger, they may cancel the concert and refund my ticket. Unfortunately, U2 were unable to comment on this piece, but I will vouch for them. What U2 would never do is send a Zoom link to everyone and say that we can all listen along to their remastered Greatest Hits Album. Bono may have more live charisma than the average Harvard professor, but there does feel like there is a difference between watching the man run his fingers through his sweaty mullet while belting out the lyrics to “Bad” in a stadium full of 72,000 people and logging into a Zoom meeting.

A university endowment is a collection of assets accrued from donations. The collection that comprises the Harvard endowment is as opaque as it is megalithic. The Harvard Management Company (HMC) is the nonprofit which manages the endowment. It is a subsidiary of the Harvard University Corporation. HMC has the singular mission “of producing strong investment results to support the educational and research goals of the University.”

This mission is a profit-driven goal. There is no consideration of ethical investing or people-focused impact. Instead, “HMC has a singular mission of producing strong investment results.” HMC further breaks down its mission into two goals: disbursing to fund the operating budget of the university and maintaining the “long-term value of endowment assets after accounting for inflation.” Each year, the endowment pays out 5% of its market value to help fund the University’s budget. In 2021 for instance, the budget was $5 billion, of which the endowment’s disbursement covered roughly one-third. The Harvard Corporation approves the final distribution amount among the schools.

HMC has the singular mission “of producing strong investment results to support the educational and research goals of the University.”

I emailed Dean Manning, the head of Harvard Law School, asking to interview him about the endowment. An assistant, a member of the platoon of administrative assistants who monitor his email account, responded to me with a link to a “terrific resource for better understanding the Endowment” that Dean Manning “asked [her] to share.” The link was to the generic endowment page. I had, of course, already read through the page, but her sending the link to me is, besides an obvious dismissal, a clear effort for University representatives to remain on the same page. They must toe the party line. Since each Harvard staffer has pushed me to the page, I will analyze the messaging on the website.

“The endowment includes thousands of philanthropic gifts, many of which were given to support specific aspects of Harvard’s teaching and research work.” Already, whoever wrote the page presents the common refrain that the University’s hands are tied when it comes to disbursing from the endowment. The dead-hand control of ancestral philanthropists apparently still regulates how the funds may be used. This chorus appears again on the finance website of the University. “[M]any donors also designate a specific purpose for which their fund can be spent. For Harvard, over 80 percent of endowed funds are subject to these restrictions. Contributions may be given in support of a specific School, program, or activity, and can only be used for those purposes.” This statement appears underneath the header “Why can’t Harvard use more of its endowment in order to cover additional expenses or reduce tuition costs?”

Already defensive, much of the University’s messaging regarding the endowment is mired with reactionary language. The response to “why not lower tuition” feels like a tired parent telling their child that money does not grow on trees. The University’s officers are weary of students, faced with monstrous tuition fees and familial pressure to accept a position at a prestigious Ivy League, asking why the $52 billion in the endowment cannot help. These students are laboring under a “common misconception that endowments, including Harvard’s, can be accessed like bank accounts, used for anything at any time as long as funds are available.”

These students are laboring under a “common misconception that endowments, including Harvard’s, can be accessed like bank accounts . . . .”

The University messaging alternates between flattering its students and putting them down. On the one hand, Harvard students are ripe with “talent, curiosity, and intelligence.” These students have “integrity, maturity, the strength of character, and concern for others.” Those very same students cannot understand the financial complexities of the endowment and labor under a “common misconception.”

The finance page of the endowment, just like the general page that Dean Manning’s assistant so magnanimously sent to me at his direction, is full of appeals to the agency. HMC cannot manage the funds as they wish because donors have attached rules to their gifts. Neither the rules nor the investments are disclosed. The money that has been pooling in the endowment and which grew over 33% last year cannot be used. These donors who designate specific uses for their funds apparently control the way in which their gifts are spent. The Association of American Universities (AAU) agrees with Harvard’s position. “Colleges and universities are legally required to uphold donor intent when managing and spending endowment income.”

According to the AAU, charitable gifts are the lifeblood of nonprofit colleges and universities. In the same breath that AAU defines charitable gifts, it argues that charitable giving should be tax deductible. It also argues that the profits from such charitable giving, through endowments, should not be taxed. After making its case for tax exemption, an already odd and seedy approach to defining endowments, AAU, just like Harvard, says that universities are “legally required to uphold donor intent when managing and spending endowment income.” These donors, many of whom are dead, thus have massive influence over university budgets and overall priorities.

Harvard is a private, nonprofit university. The AAU has staunchly opposed taxes on private university endowments arguing that such a tax would reduce “support for student aid, academic programs and research, and redirects funds to the government.” Harvard uses similar language to justify the endowment system. “Our endowment supports many aspects of our work, from student financial aid to neighborhood programs, from museum and library preservation to campus activities, from faculty and fellow positions to scientific advancement.” The messaging about research and financial aid, meant to reassure the reader, is prevalent throughout universities with endowments.

At Yale, for instance, each Dean blurbs about the endowment. They tout it saying it “sustains exciting research across the Graduate School.” Yale’s Provost, Scott Strobel. “The endowment helps Yale’s people—dynamic teachers, world-class scholars, pioneering researchers.” Dean of Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, Lynn Cooley. “Income from the Endowment covers a significant portion of each student’s education, supports faculty research…” Dean of the School of Management, Kerwin Charles. “Endowment support is essential for developing cutting-edge conservation research.” Director of the University Art Gallery, Stephanie Wiles. “[O]ur endowed funds enable the Library to pursue its mission of fostering research.” University Librarian, Barbara Rockenbach. Beyond research, “[t]he Endowment also makes this education accessible to all students, regardless of their financial means; over half of them receive financial aid without requiring debt.” Stanford University plays the same tune. “The payout supports nearly every part of the university, including faculty salaries, research, student services, libraries, athletics, and student financial aid.”

Schools cite the same two justifications for the existence of endowments: research and student financial aid. If you believe that universities should not behave like “a hedge fund with a library,” as Connor Chung of the Fossil Fuel Divest Harvard organization calls it, then you must hate scientific progress and poor students. Universities are the sources of some of the greatest scientific discoveries. Thank you, University of Toronto, for discovering the first black hole. Thank you, University of Cambridge, for founding computer science. And yes, the target of this piece, thank you, Harvard, for the discovery of the smallpox vaccine. With no detraction intended to research, I question the intent of the donors who so strictly fund such research. In one breath, the rhetoric about endowments is one of helplessness. The universities cannot disperse their funds to solve immediate problems because they must adhere to the stipulations of the donors who first gave money. In the next breath, these same universities praise such donations for their funding of a variety of research work. Do donors control what kinds of research are conducted?

Schools cite the same two justifications for the existence of endowments: research and student financial aid.

Donors have power. Through charitable giving, donors undermine public spending and democracy. On tax returns in the U.S., people can announce charitable donations as a deduction from their income. This charitable giving deduction incentivizes wealthy, high-income individuals to donate to charities. The effect of this policy is to provide greater tax control to the wealthy. The policy assumes that the government may not know how to best spend the high-income person’s taxes. It provides such people with the opportunity to direct how the public benefits from their taxed income. This system may make taxes feel more palatable to the wealthy who can direct their taxes to organizations about which they care. That said, the direction that the individual decides to take cannot align with the interests of the public. Assuming representative governance and no corruption, perhaps an impossible premise, elected officials are the people’s will. Their decisions on how the government’s money should be spent are then the people’s decisions on how public money should be used. The charitable giving exemption subverts the people’s will.

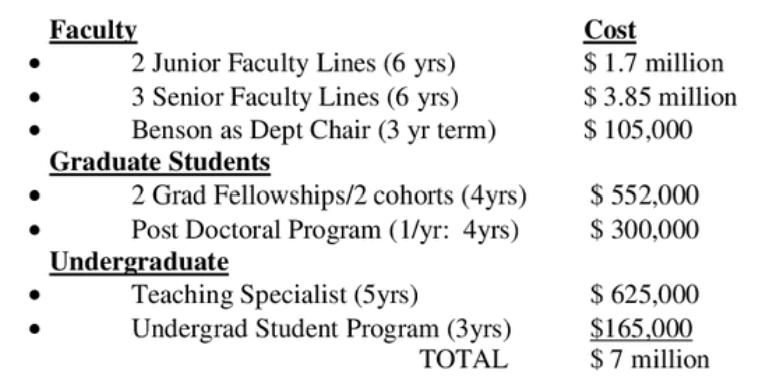

Within the context of higher education, donors may gift part of their taxes to universities. These gifts form endowments. There are several kinds of gifts. Among them, restricted and permanent endowments are democratically problematic. Restricted endowments cannot fund general use and must be spent on specific activities. Permanent endowments “prohibit the use of the original gift corpus; only the income generated from the investment may be spent.” Through restricted and permanent endowments, wealthy donors may influence the kind of activities with which the university may engage. This influence on a university’s research and hiring contradicts the conception of education as a public good. Most universities are non-profits and are taxed as such. The U.S. exempts institutions like Harvard from the taxes they would levy against a for-profit corporation. Exempting universities allows them to use what would have been the public’s money for their own purposes.

The charitable giving exemption subverts the people’s will.

The university, within the tax scheme, is thus a public good. A public good is nonexcludable and nonrivalrous. Nonexcludable means that it cannot have any financial barrier to enjoying the good. The university cannot charge for its services. Nonrivalrous means that no matter how many people enjoy the good, each individual’s enjoyment is unaffected. National defense, lighthouses, radio stations, asteroid deflection programs, YouTube, and more are all nonrivalrous. Everyone can enjoy not being hit by asteroids. Each person can enjoy this privilege without detracting from the enjoyment of someone else.

Public goods include asteroid deflection programs. Photo by Diego PH.

Quite obviously, Harvard and its ilk are not public goods. They charge tuition which makes them excludable. If you cannot afford such tuition, you are excluded from the university. Ultimately, all in-person education is also rivalrous at scale. Ten people in a seminar course would have a different experience if one thousand people tried to take that same course. Ignoring the extremes of scaling education, universities could and should strive to be non-excludable financially. As alien as it may seem to a U.S. audience, charging tuition is optional. Germany, Norway, France, Iceland, Sweden, the Czech Republic, Luxemburg, Mexico, Brazil, and a slew of other nations offer free higher education to their citizens.

![[F]law School Episode 1:](https://theflaw.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/Class_FB-1-640x427.jpeg)