Dodging Damages

How Corporate Lawyers Are Corrupting Civil Litigation

Elyssa Alfieri

November 6, 2023

How much does it cost to obstruct justice? For Facebook and its lawyers at Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher, it was $925,000. That is the amount that U.S. District Judge Vince Chhabria of San Francisco ordered Meta Platforms Inc., Facebook’s parent company, and Gibson Dunn to pay plaintiff’s lawyers for their bad-faith litigation misconduct in a class action suit. The class action suit accused Meta of harvesting and misusing user’s personal data without their knowledge or consent. Judge Chhabria described the amount as “loose change” for a company like Meta, whose annual earnings surpassed $115 billion in 2022, and even for a law firm like Gibson Dunn that grosses $2 billion annually. It’s obvious that these monetary sanctions are insignificant to Meta and Gibson Dunn, so what will prevent them from obstructing justice again? What’s at risk?

Civil litigation is an important legal tool to hold powerful corporations accountable for their wrongdoings. When an individual sues a corporation for violating their rights they do so as a plaintiff in a civil lawsuit. To avoid paying damages, corporations and big corporate defense firms engage in deliberate misconduct that makes civil litigation unfairly difficult and expensive for their opponents. The failure to address such misconduct jeopardizes plaintiffs’ ability to secure justice.

Source: Chesnot/ Getty Images

What is Civil Litigation?

Civil litigation allows a person or groups of people (the plaintiffs) to sue another person or entity, such as a corporation, (the defendant) over a harm or wrongdoing. Unlike the criminal legal system that handles potential violations of criminal law, the civil system deals with the private rights of individuals. Civil litigation encompasses numerous types of disputes including employment rights, personal injury, and class action lawsuits. Civil cases typically compensate the wronged party by awarding damages at the close of trial. However, civil trials can be expensive and time-consuming, so it is not uncommon for parties to reach a settlement instead. While settlements offer plaintiffs some compensation, it is often considerably less than what the court would have awarded.

But what is litigation misconduct? It refers to instances where the rules of litigation are manipulated or violated in a bad-faith effort to delay, harass, or achieve an unfair advantage. While misconduct may occur at any stage of litigation, it often occurs during discovery. Discovery is the formal pre-trial process where opposing parties exchange information about the witnesses and evidence they will present at trial. To appreciate the impact of misconduct, consider how our litigation system depends on the good-faith willingness of litigants and lawyers to comply with its rules. Lawyers have an ethical duty, as officers of the court, to disclose the facts necessary for the court to make an informed decision. However, one side’s refusal to faithfully comply with discovery procedures, by withholding or altering evidence, throws the whole system into flux.

Judge Charles Renfrew summarized the issue in 1978:

“My experience in civil litigation has convinced me that abuse of the judicial process, while difficult to detect and prove, is widespread. It occurs most often in discovery matters. Unjustified demands for discovery and refusals to provide discovery drag out litigation and drive up its costs. Fabrication and suppression of material facts is a regrettably common occurrence, although lawyers and judges are often reluctant to admit it. These abuses affect actual litigants and deter potential parties from resorting to the judicial process.”

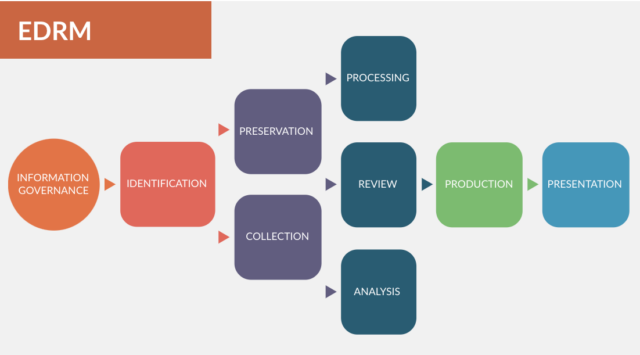

It is likely that discovery misconduct has only gotten worse since 1978, since virtually all discovery is now electronic. Electronic discovery, commonly referred to as e-discovery, is the process of identifying, collecting, and producing electronically stored information such as emails, documents, texts, and voicemails. The intricacies associated with e-discovery provide a ripe opportunity for corporate defense attorneys to disguise their bad-faith actions as confusion or incompetence.

The Electronic Discovery Reference Model. Source: Exterro

Joel Fleming is a litigator and a partner at Block & Leviton LLP, a plaintiff-side law firm that represents investors against large corporations. Like many plaintiff-side attorneys, Fleming often faces delays in the discovery process. “We give [defense counsel] a list of people whose inboxes we want searched and keywords that we want used on those inboxes.” He explained. “They’ll say ‘oh that’s crazy we could never do that.’ To substantiate that, they need to give us the reports showing how many documents they actually have to review. That inevitably takes a long period of time… four, five, six months from issuing the requests to getting them in the door.” There are reasons to doubt the defense-counsel’s claims that they are incapable of promptly meeting these discovery requests. Instead, “it is a matter of abusing civility norms and dragging out and delaying” Fleming said. “Computers can process things pretty quickly, and if you look at sort of the rare instances where there is expedited litigation between large corporate parties represented by big law firms on both sides it turns out they can move really quickly,” He explained, citing the litigation between Twitter and Elon Musk that, in his words, produced large quantities of documents in a period of four to six weeks.

“it is a matter of abusing civility norms and dragging out and delaying”

There is a strong incentive for the defense to delay litigation because it often results in a higher cost of litigation. Higher costs place a larger burden on the plaintiff side because “on the defense side, your client is paying. On the plaintiff side, that’s not happening. Sometimes you’re not getting paid at all, sometimes for years. And that does, unfortunately, put people in a position where they must settle cases and move towards settlement, maybe prematurely,” David Seligman, who has been litigating a class action lawsuit on behalf of current and former Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) detainees, told the [f]law.

Not only are attorneys aware that misconduct causes delays, but they also know that collaboration can prevent it. The Federal Judicial Center and the American Bar Association (ABA) Section of litigation published a study in 2009 that showed 95 percent of respondents were in agreement that collaboration and professionalism by adverse counsel can reduce client costs. Approximately the same percentage of respondents in the Federal Judicial Center survey agreed that “attorneys can cooperate in discovery while still being zealous advocates for their clients.”

“Every single thing you do as a defense lawyer is intended to drag the litigation out.”

Unfortunately, many defense-side attorneys are not interested in cooperation. Tom Sobol is a plaintiff-side litigator who spent the first 17 years of his career working in a large corporate defense firm. He told the [f]law that “Every single thing you do as a defense lawyer is intended to drag the litigation out. Everything you do. If somebody says, ‘Can you get back to me tomorrow?’ You get back to them next week. If somebody says, ‘Can you be available on this day?’ You can’t be. If a court sets a hearing, you’re not available. Ever. If there’s an opportunity to seek to take an interlocutory appeal, you seek to take the interlocutory appeal.” Some of the big corporate defense firms even gave their attorneys incentive awards if their case was delayed for a certain period of time, Sobol said in an interview with the [f]law.

Placing Facebook and Gibson Dunn’s Misconduct in Context

Judge Chhabria described Facebook and Gibson Dunn’s misconduct as “an example of a wealthy client (Facebook) and its high-powered law firm (Gibson Dunn) using delay, misdirection and frivolous arguments to make litigation unfairly difficult and expensive for their opponents.” He further wrote that, while this type of misconduct is common, many large corporations aim to drive down a case’s settlement value, Facebook and Gibson Dunn’s misconduct was “unusually egregious and persistent.”

A few of the plaintiff-side attorneys I spoke with did not share the view that this misconduct was unusual. John Roddy, a plaintiff-side attorney and partner at Bailey Glass, told me that “the misconduct described [in the order] … is not extraordinary in any respect. The fact that they got called out for it is what’s extraordinary, that kind of hiding the ball.” Roddy has litigated cases over the last two decades that have returned more than $1 billion to consumers harmed by marketplace misconduct. He told me that not only is this kind of misconduct “pretty much the norm” but that he believes it has gotten worse over the last decade.

Framing their actions as those a zealous advocate would employ and accusing the plaintiffs of their own wrong-doing implies that Gibson Dunn, like other large law firms, is comfortable breaking the rules for their clients.

Throughout the case Gibson Dunn attorneys insisted that they were acting as zealous advocates, even when directly violating court rules. One example was when Facebook’s lawyers deliberately prevented the plaintiffs from obtaining information during depositions by instructing witnesses not to answer questions that were within the scope of the deposition notice. Another was Facebook and Gibson Dunn’s refusal to produce non-lawyer communications that were not privileged and evidence that directly related to the central allegation of the case. Facebook and Gibson Dunn went as far as accusing the plaintiffs’ lawyers of delaying the case, which the court described as an attempt to “gaslight their opponents, not to mention the Court.” Framing their actions as those a zealous advocate would employ and accusing the plaintiffs of their own wrong-doing implies that Gibson Dunn, like other large law firms, is comfortable breaking the rules for their clients.

How Judges Can Address Misconduct

Federal district courts have the power to sanction litigation misconduct, like the bad-faith efforts to delay described by Tom Sobol. Sanctions refer to a judge ordering a penalty due to a lawyer’s behavior.

The Federal Rules of Civil Procedure (FRCP) govern civil proceedings in U.S. federal courts and authorizes the court to impose sanctions when certain judicial rules are violated. Federal courts also possess broad “inherent powers” to award sanctions. In Chambers v. NASCO Inc., the Supreme Court held that the court possesses an “inherent power to sanction a party’s bad-faith conduct” and that a court may exercise this power by requiring the sanctioned party to pay the opposing party’s attorney’s fees. Notwithstanding this capability, there is a general expectation among federal judges that attorneys should resolve disputes among themselves, especially pre-trial disputes like discovery.

Judge Virginia Kendall, a U.S. District Judge for the Northern District of Illinois, wrote that judges in her district had “a distaste for imposing sanctions” with one judge going as far as describing himself as “sanction allergic.” Judge Kendall described a perception among judges that “a monetary sanction is imposed only for the most egregious violations,” which implies that judges are willing to accept a certain level of misconduct. This mentality was demonstrated in Judge Chhabria’s order when the court opted to only sanction Facebook and Gibson Dunn “for the worst of their consistently bad behavior.”

Judge Kendall described a perception among judges that “a monetary sanction is imposed only for the most egregious violations,” which implies that judges are willing to accept a certain level of misconduct.

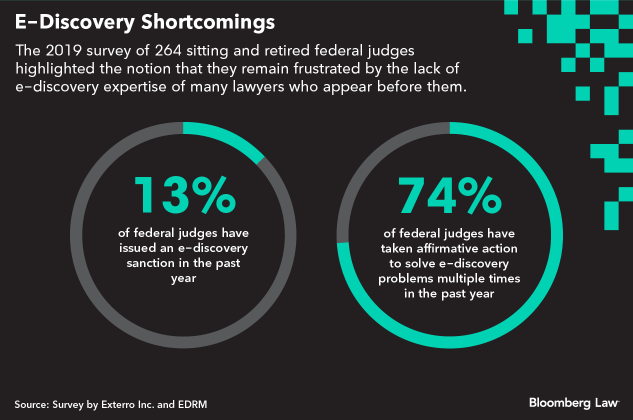

A 2019 study by Exterro and EDRM/Duke Law surveyed 260 sitting and retired federal judges. The study found that over the past year, three quarters of judges issued warnings or scheduled additional conferences to solve e-discovery problems, which suggests a significant amount of misconduct is taking place. Yet only 13% of judges had issued an e-discovery sanction. This is consistent with that idea that “most judges typically don’t see it as their role” to mediate e-discovery disputes, as U.S. Magistrate Judge Elizabeth Laporte said to Bloomberg Law. This view may lead judges to neglect to use their powers to sanction.

Source: Bloomberg Law

Requesting Court Sanctions

The expectation that attorneys should resolve disputes among themselves, coupled with judges’ general distaste for imposing sanctions, often means that plaintiff-side attorneys must pick and choose which issues of misconduct to bring before the court.

Lindsay Nako is the director of litigation and training at the Impact Fund, an innovative legal nonprofit that represents individuals and classes in strategic civil rights litigation. She has represented individuals and classes of people who have experienced workplace discrimination, denial of public benefits, and other civil rights violations. In describing the expectations that federal judges have for attorneys, Nako explained, “the court does not want to see us running in to have them referee every single dispute.” She described making meaningful attempts to meet and confer with opposing counsel outside of court. Nako, like many plaintiff-side attorneys, attempts to exhaust all options before turning to the judge. “It’s really my job in meet and confers to do as much as I can outside of the court,” she told me. “If I go to the judge right now, will they understand that I’ve run out of options, or will they feel like I’m coming to them with unnecessary work?”

Beyond just limiting how many issues of misconduct to bring to the court, plaintiff-side attorneys also must consider whether a judge is receptive to sanctions at all. There is a “practical reality of certain judges just being much less receptive to those sorts of considerations,” an attorney said, referring to requests for sanctions.

This consideration is exemplified by a case Joel Fleming was involved in where during discovery a prominent defense-side firm altered evidence by deleting damning words from documents. Rule 37 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure enumerates sanctions the court is authorized to impose when a party fails to preserve electronically saved information. The potential sanctions, such as presuming the lost information was unfavorable or entering a default judgment, are serious penalties that correlate to the offensiveness of the misconduct. However, the judge presiding the case had a reputation for disfavoring sanction requests and Fleming was forced to make the strategic decision not to seek sanctions. “We would have acted differently if we were in front of a different judge,” he explained. “But we didn’t think that was in the best interest of our client for this particular case.”

![scales - Logo for The [F]law](https://theflaw.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/flaw_scale_divider.png)

Judges are hesitant to impose sanctions, but in the rare cases they do, how effective are they? Monetary sanctions, at least at the rates they are currently imposed, seem unlikely to deter large corporate clients and their attorneys. Barring the immense wealth of both Facebook and Gibson Dunn, a $925,000 sanction is minor. It is a small proportion of the ultimate $725 million settlement.

There is no way to know for sure if the misconduct lowered the settlement value, but there is good reason to believe it did. An inability to access evidence may have convinced the plaintiff that they had a weaker case than they did, or the continual delays may have made the cost of litigation too expensive to continue. Facebook and Gibson Dunn’s misconduct would have only needed to lower the total settlement value ($725 million) by more than $925,000, which is less than .14 percent of it, to have come out in a better position than if they had not engaged in the misconduct. For a class action suit of this size, the odds that the value was diminished by more than .14 percent seems probable.

If wealthy companies and law firms are still in a relatively better position because of their misconduct, then monetary sanctions are not a sufficient deterrent. Joel Fleming agreed, saying that “I don’t think monetary sanctions, at least in these big cases with big law firms and companies with 11 figure market caps, are all that effective.” John Roddy echoed a similar sentiment saying that “the sad reality of our system is that the people who have the most money and resources most of the time prevail.”

“the sad reality of our system is that the people who have the most money and resources most of the time prevail.”

In this case, Judge Chhabria’s order is being viewed by many as an attempt at making an example of Facebook and Gibson Dunn, and in turn drawing attention to the larger systemic problem of corporate litigation tactics. Negative public attention could serve as a deterrent effect. Before the sanctions were imposed, Gibson Dunn partner Rosemarie Ring said her team was “mortified” by statements alleging misconduct. Additionally, some plaintiff-side attorneys expressed skepticism that public attention would truly deter future misconduct because wealthy clients, as one lawyer said, would “look at what happened at Facebook and say ‘yeah, that’s exactly the kind of lawyer I want. That’s someone who would go take a bullet for me.’” Gibson Dunn attorney Orin Snyder, who was lead counsel on the case before Rosemarie Ring, has made a reputation for himself through utilizing aggressive legal tactics. Snyder told Law360.com, referencing his past work on behalf of Cablevision System Corp., that he had “a take-no-prisoners” approach to the litigation and that it was “a scorched-earth litigation from the moment I took over the case.” Someone who has portrayed himself as a “hired gun” would likely use such sanctions as evidence of how far he is willing to go for future clients.

There are other penalties outside of monetary sanctions that judges can impose. A few other examples are evidentiary sanctions, referring an attorney to the American Bar Association, individually sanctioning an attorney (as opposed to the law-firm and/or client) and what is referred to as “death penalty sanctions.”

Death penalty sanctions, which occur when the court enters a default judgment against the sanctioned party, are typically only utilized in the most egregious forms of misconduct. On the other hand, evidentiary sanctions, which limit the evidence or testimony that may be introduced by the sanctioned party or limits that party’s ability to object to the opposing party’s evidence, are more commonly used because they are not case-ending and therefore are appropriate to address various levels of misconduct. If monetary sanctions are insufficient to deter wrongdoing, then perhaps courts should turn to evidentiary sanctions that could ultimately change the outcome of a case. It seems likely that defense-side attorneys would be hesitant to engage in misconduct if it meant losing a case for their clients. However, the exact solution is unclear and may be a combination of different approaches.

The Costs of Misconduct

Misconduct is not without harm. By pushing the outer limits of the discovery process with the goal of forcing plaintiffs’ lawyers to accept a discounted settlement offer, corporate defense attorneys are assisting corporations in avoiding just compensation to their victims.

Most misconduct causes delays that impact the desire of members of the class to continue litigation. “In many cases people really need to get a resolution… they’re trying to do the right thing but their families or their friends are saying, why are you still doing this? It’s five years later.” John Roddy explained. “So yeah, we’ll certainly settle cases for less than we should have if the playing field were level.”

“In many cases people really need to get a resolution… they’re trying to do the right thing but their families or their friends are saying, why are you still doing this? It’s five years later.”

A failure to receive a just and speedy settlement also impacts the public’s faith in the legal system, which could impact claimants’ willingness to engage in civil litigation in the first place. As Judge Charles Renfrew wrote, “these abuses affect actual litigants and deter potential parties from resorting to the judicial process.”

If the public loses faith in the judicial process, there will be cases of corporate abuse that are never brought to light. Many consumers and workers who have been harmed by wealthy companies often deal with stark information asymmetries. Without the judicial process, in particular discovery, these victims will be unable to access the evidence necessary to prove their claims.

Judges are empowered with the ability to sanction misconduct for a reason, and cases like Facebook’s recent class action lawsuit illustrates not only why they should exercise that power, but how they should better utilize it. If the victims of corporate abuse are brave enough to litigate against powerful actors, then the legal system should at least guarantee them a fair fight.