Nestlé: Pure Life or Impure Lies?

Examining the Swiss company’s unethical practices in Pakistan

Hafsa Ahmad

September 17, 2024

A beautiful young mother is sitting cross-legged on the floor with her baby boy, Ali, playing in her lap. She scribbles down a grocery list: onions, oil, tomatoes, lentils. She’s tucked a handful of bills into the list she’s balancing on her knee—700 Pakistani Rupees (Rs.), just about $6. As she hands the list to her mother, she says with concern “Ammi [Mom], things have gotten so expensive—I’ve only written down the essentials. Will you take a look, too?”

Running down the list, her mother chastises her, “Cerelac is an essential, too–you didn’t even include that! Beta [Daughter], in the first twelve months, a baby grows three times its weight. That’s why, at this age, Cerelac is an essential for Ali, too!”

Ali’s mother, taking the list back, exclaims, “How could I forget Cerelac?” As the scene cuts to Ali’s mother feeding Cerelac to a happy, clapping Ali, she turns to the camera and smiles, “Because when it comes to Ali’s growth, no compromises!”

In the backdrop of this heartwarming exchange between baby Ali’s loving mother and grandmother is a more sinister story from Sialkot, Pakistan in the 1990s of a young mother and her four month old. She breastfed her baby for a month before her doctor told her that breastmilk was not suitable for her child. Instead, the doctor encouraged her to switch to his recommended brand of baby formula. On his advice, she began bottle feeding her baby and abandoned breastfeeding. Two months later, the mother and child returned to the hospital. The baby, for the past sixty days, had been suffering from chronic diarrhea and acute dehydration. Despite the efforts of the medical staff at the hospital, the four month old died. The doctors attributed the baby’s premature demise to the switch from breastmilk to bottle feeding. The mother, like many young women in Pakistan, had been advised to use the breastmilk substitute but had neither understood the proper preparation technique, nor had access to regular clean drinking water with which to mix the formula. Unfortunately, this was far from the only incident of infant death due to a switch from breastmilk to infant formula products at a premature age, in an area with low literacy rates and unsafe drinking water.

Meanwhile, employees at the brand’s office in Pakistan promote infant formula and baby food using outrageously aggressive methods. One whistleblower, working as a “Medical Delegate” at this company, revealed that the company encouraged him to ply nurses with popular Nestlé products to allow him into maternity wards in their hospitals. He would then directly approach new mothers to offer them samples of their infant formula products despite medical advice recommending that mothers exclusively breastfeed for the first six months, and encourage them to try bottle feeding rather than breastfeeding. During these visits, he would inquire if the doctors had prescribed their brand of breastmilk substitute products, and the nurses would write out prescriptions for such baby formula, rather than guiding the young mothers on breastfeeding their newborns.

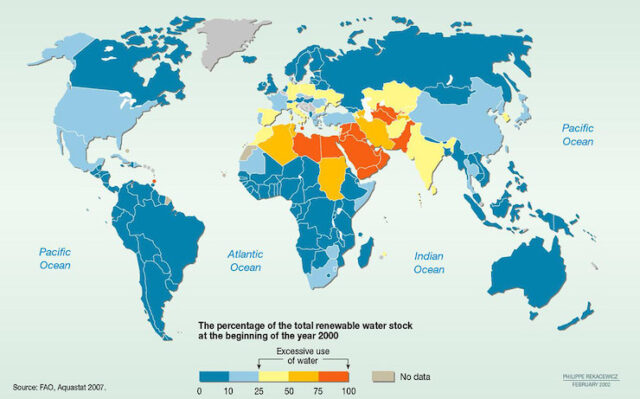

Not far from Sialkot is another city facing a different sort of problem with a multinational giant: Sheikhupura, Pakistan. Here, two large water extraction plants pump water at an alarming rate for bottling into a neatly packaged product. The two plants sit above a major underground well which serves as a source of water for the nearby village of Bhati Dilwan. However, ever since the erection of the plants, villagers have been falling sick, purportedly as a result of the depletion of their local water sources due to Nestlé’s extraction from a groundwell beneath the village. What’s more is that the villagers complain that they are unable to extract water from the groundwell they had used as a source of drinking water for decades, leaving them parched without drinking water. What do the plants manufacture and sell? Bottled drinking water.

One whistleblower, working as a “Medical Delegate” at this company, revealed that the company encouraged him to ply nurses with popular Nestlé products to allow him into maternity wards in their hospitals.

The common denominator in the commercial of intergenerational love, the tragic death of the baby in Sialkot and the community’s water woes in Bhati Dilwan is Nestlé, a Swiss multinational company. In 2023, Nestlé Pakistan (“Nestlé”) grossed over Rs. 200 Billion [$72 Million]. In order to appreciate the scale of this revenue: the Prime Minister of Pakistan in 2023 announced austerity measures aimed at saving the government a total of Rs. 200 billion.

Yet, somehow Nestlé escapes liability in Pakistan for the issues surrounding its baby formula products and its draining of the groundwell in Bhati Dilwan. Despite significant media coverage clamoring for the government to take action and demand accountability from the multinational company, years have passed, and answers still elude the public.

Nestlé’s Breastmilk Substitute Campaign

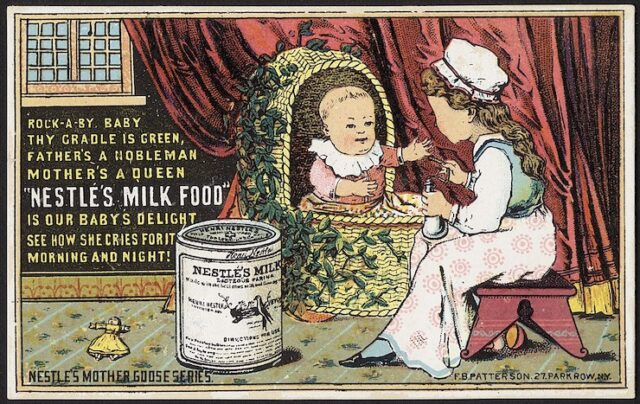

A vintage advertisement for Nestlé’s baby food

Nestlé was an early entrant to the infant formula market in Pakistan. The company spearheaded a push towards infant formula through direct-to-consumer advertising and indirect advertising through health professionals. Many of their practices, described below, were violative of multiple provisions of international codes, including the World Health Organization (WHO) International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes and the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) Code for the Protection of Breastfeeding and Young Child Nutrition.

In 1998, whistleblower Syed Aamar Raza risked his career (and life) to reveal a firsthand account of Nestlé’s unethical practices. According to Raza, company policy instructed him to bring products such as Nestlé Cerelac and Nescafé to nurses in the maternity ward. These nurses would admit him into the ward to meet young mothers still learning how best to help their babies grow, similar to Ali’s mother. During these visits, Raza would inquire if the doctors had prescribed any Nestlé products, and the nurses would write out prescriptions for Nestlé baby formula, rather than providing guidance on breastfeeding.

On another occasion, Raza received a request from a military doctor asking for two air conditioners for his hospital, claiming it was for the comfort of his patients. Raza was told to arrange the necessary “support” for the doctor. A month later, the doctor issued a circular in the hospital insisting that only Nestlé products should be used.

This highlights the extent to which Nestlé was willing to go to secure its market share, even to the detriment of patient care and ethical standards within healthcare institutions. Although the medical professionals and staff undoubtedly played a role, Nestlé’s exploitation of their vulnerable positions was a glaring violation of yet another provision of the WHO Code which prohibited financial or material inducements to health workers or their families.

There was a concerted effort to promote the use of baby formula as a breastmilk substitute, encouraging mothers to abandon breastfeeding.

In addition to the above, Nestlé hosted special medical conferences where the company paid for travel and accommodation of pediatricians and their families. They also offered indirect financial incentives to medical professionals to prescribe formula to mothers with children under the 6 months, despite guidelines recommending exclusive breastfeeding during this period. Often, the company pressured its employees to track the numbers of formula prescriptions per hospital or clinic.

In its direct-to-consumer marketing, Nestlé promoted baby formula directly to new mothers by hosting “baby shows” where employees distributed free samples to young women. There was a concerted effort to promote the use of baby formula as a breastmilk substitute, encouraging mothers to abandon breastfeeding. The company marketed products not only as healthier for the child but also for the mother, emphasizing convenience and modernity. Advertisements portrayed breastfeeding as primitive and formula feeding as a symbol of progress and sophistication.

This narrative suggested that women who breastfeed lack access to ‘better means’ of nourishing their children and deprive their children of superior nutrition and growth. The marketing campaigns were highly influential, shaping societal attitudes towards breastfeeding and contributing to a decline in breastfeeding rates in many countries. This practice undermined the importance of breastfeeding and prioritized the promotion of Nestlé products over the well-being of infants.

Shortly after the extent of Nestlé’s practices came to light, public pressure led to the passing of the Protection of Breastfeeding and Young Child Nutrition Ordinance 2002 (“Ordinance”). However, despite the high promises of the Ordinance to regulate the marketing and promotion of designated products including breast milk substitutes, effective implementation of the Ordinance has fallen severely short. This is evident even in Nestlé’s aggressive marketing today.

Today, Nestlé’s commercial campaigns and misleading packaging remain the target of scrutiny. For example, the Nestlé advertisement featuring Ali and his mother suggests that Cerelac is a healthy food for children under the age of 12 months, citing health statistics to lend an air of medical credibility to the product brand. Since the product Cerelac is a food product, and not a medical product, claims of health and nutritional development are not required to be verified before promotion.