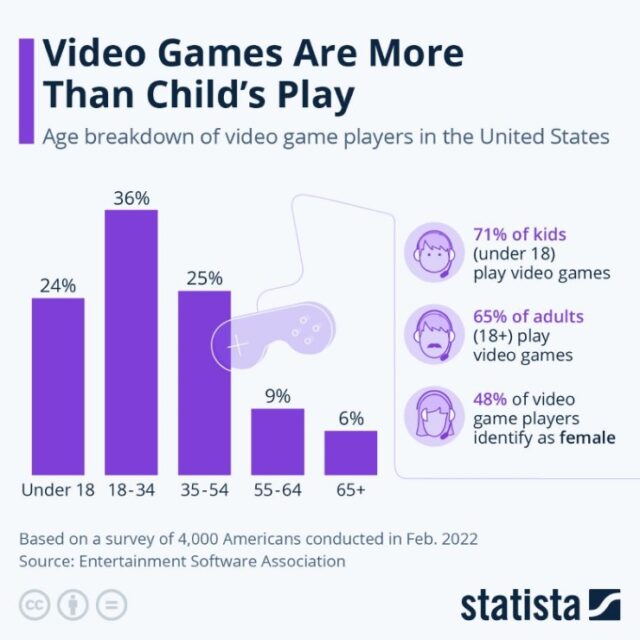

The big deal is what SS:KTJL and other production-expensive AAA games represent. The video game industry today is bigger than ever before and shows no signs of slowing down. It is expected to reach a global valuation of over $280 billion. Consumer spending in the US alone totaled over $57 billion last year. The gaming audience also continues to grow, with nearly 3.5 billion users worldwide in 2023.

What’s more, video games are gaining more mainstream cultural prominence, with “transmedia” adaptations like The Super Mario Bros. movie and The Last of Us TV series. Many of the best-selling video games of all time are household names – think Pokemon, Minecraft, and Wii Sports. All of these franchises and others have earned billions of dollars in sales.

The video game industry today is bigger than ever before and shows no signs of slowing down.

Yet it often feels that in recent years, large-scale gaming flops are less and less surprising. With each lauded new Legend of Zelda, there is a Redfall, released by an innovative studio but plagued with technical issues and was essentially unfinished.

Cyberpunk 2077 was similarly condemned on release in 2020 as bug-ridden and almost unplayable: Sony even unprecedently removed the title from the PlayStation store. (The game’s in much better shape now.) The hype behind Cyberpunk 2077 – its creator, CD Projekt Red, had made one of the most praised games of all time – certainly didn’t help.

What’s going on here? Why are AAA games getting more and more expensive to make (and buy), yet receive increasingly disappointed fan responses?

Meet Your Makers: The Plight of the Developer

A deeper explanation may be found with the developers, aka “devs.” In very generalized terms, devs are people who make the games we play. They include the programmers making base code, designers generating each level, artists conceptualizing characters and worlds, and writers crafting story.

Of course, many other folks play an important role in getting a game from code to console, including voice actors, production managers, audio engineers, and quality assurance testers. Studio executives, media relations, and publishing agents can be no less essential to effectively getting games to a target audience. Yet, without the devs actually creating games, the industry certainly would not have the massive growth, success, and creative output that it enjoys today.

Unfortunately, despite their invaluable contributions, developers in many video game companies face excruciating working conditions. A major issue devs face is “crunch,” or long periods of intense, unpaid overtime work in order to meet tight production deadlines. Crunch exacerbates, and in many ways encapsulates, developers’ persistent problems of low pay, long working hours, and a culture of burnout.

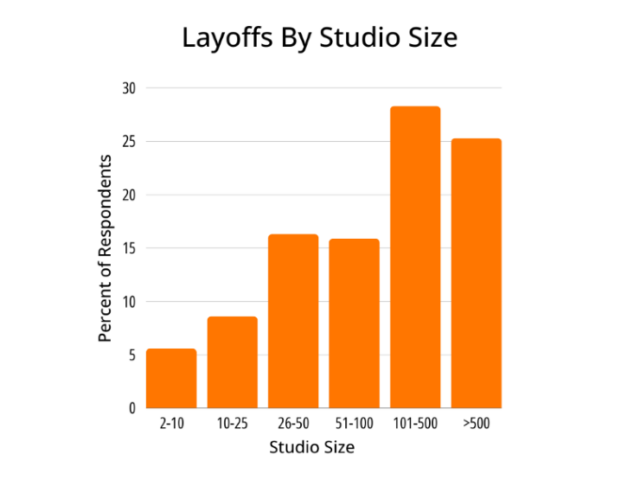

Most recently, developers have suffered from a massive round of layoffs, further exacerbating their situation. These layoffs – some of the largest yet – are in no small part related to corporate restructuring and companies’ attempts to maximize profitability. And the gaming industry remains plagued with issues of sexual harassment and discrimination, alongside longstanding diversity problems.

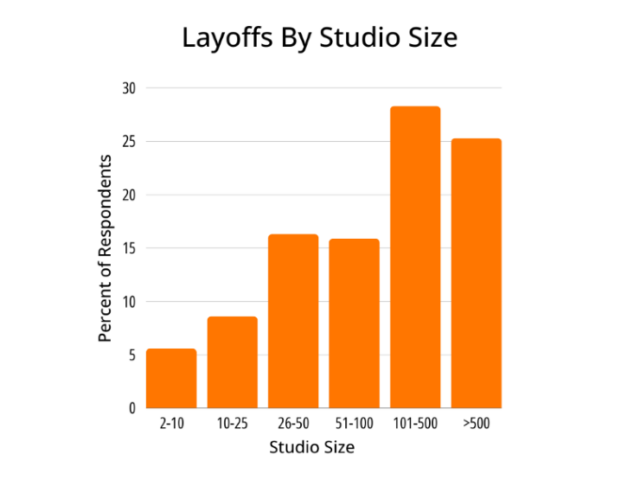

Graph of survey data retrieved from TakeThis.

Why do devs have to regularly crunch? And how does that relate to recent AAA flops? It turns out that the structure and culture of the gaming industry – particularly the AAA scene – fuels both of these issues.

Large publishing companies, motivated to increase shareholder profits, contract with studios to release games on specific deadlines and with apparent revenue-increasing features (e.g., microtransactions and season passes). Studios, seeking to build their reputations and also make money, have to accept publishers’ conditions. Devs are ultimately left to meet these production requirements in one way shape or form – which often means intense crunch before deadlines.

Yet the industry is so varied that generalizations can be difficult to make. In fact, there may be insights if we look away from the AAA industry. There are no shortage of smaller, yet no less creative, independent (better known as “indie”) games and studios – in fact, they might be charting a path forward to an alternative, healthier kind of game development.

Devs are ultimately left to meet these production requirements in one way shape or form – which often means intense crunch before deadlines.

Choose Your Character: What Kind of Industry is Gaming?

To learn more, I spoke with Professor Johanna Weststar, who has studied labor in the video game industry for over a decade. She told me that, in a nutshell, the industry today is very well-organized financially, but is not so organized culturally. It’s important to remember that the industry is still relatively new, having only really emerged in the 1970s. After all, video games started with passionate devs in their garages, starting their own small studios. Perhaps because of this, “[t]here is something about the industry that has always resisted formalization in some ways, at least in terms of its cultural mentality.”

The largest, multi-billion dollar companies in the gaming industry today include massive conglomerates, publicly traded corporations, hedge funds, and venture capital – the kinds of entities also prominent in the wider tech industry. Attorney Brandon Huffman, who regularly deals with clients in the gaming industry, explained that games today are often financed through publishing deals, distribution and exclusivity deals, and, more recently, venture capital funding.

However, while financing game production has become more sophisticated, employment structures have not likewise matured. In that sense, explained Prof. Weststar, video games behave more like other creative industries, such as movies or TV.

“[t]here is something about the industry that has always resisted formalization in some ways, at least in terms of its cultural mentality.”

Dianna Lora, who has experience in digital distribution, licensing, and game production management, emphasized this internal tension: “This is the conversation that the industry is having right now.” Many games in recent years, from indies like Ori and the Blind Forest to AAA blockbusters like God of War: Ragnarok, are artistic masterpieces in their own right. The Game Awards could even be considered the industry’s Oscars-equivalent.

Image generated through the website’s “Share the Winner” link.

Yet gaming also veers towards resembling the greater tech industry. As Dianna told me, game companies rush to invest in the hottest new tech things (e.g., Metaverses, NFTs). However, this drive “doesn’t really balance out in the 3rd or 4th quarters,” with companies often facing overblown budgets. Instead of “taking the hit like a normal company would,” gaming companies correct by cutting costs – including by laying off developers.

The Chosen Ones: Getting (and Keeping) Jobs in Gaming

The project- and portfolio-based nature of game development massively affects developers’ employment situations, not too unlike other artistic industries. Many studios, for instance, hire developers only for the length of specific projects. Large game companies like Ubisoft might shift developers between their multiple studios. Devs, meanwhile, advance their careers by showcasing their skills via building a portfolio of completed projects they’ve worked on.

I spoke with one (now semi-retired) developer, Chris Soares, who stuck with Cat Daddy Games (a studio under the publisher 2K Games) for about twelve years. Heads of smaller studios, however, told me that their team composition ebbs and flows depending on each project – though the studios do try to retain some devs as long as possible.

What all this means, according to Prof. Weststar, is that “the way the industry is designed works against some of those things that we might think are natural employment protection . . . this isn’t a place where people get a job when they’re young and they work their way out through an internal career ladder and get security.”

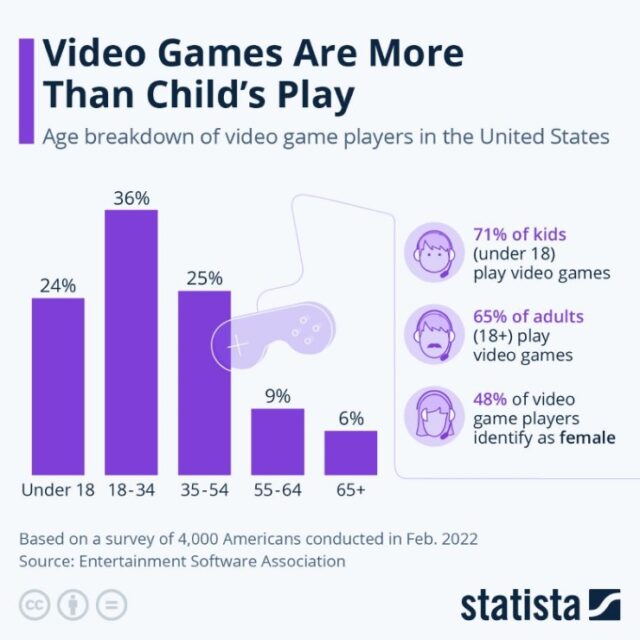

Infographic retrieved from Statista.

Studios have leverage in choosing which developers to hire: As Dr. Rachel Kowert, research director at TakeThis and an expert on video game psychology, puts it, video games are a “cool kids club.” And devs can’t be too picky when they need credit on successful projects from accomplished studios to bolster their portfolio.

“There are lots of young keen folks who would just give their right arm to work in games . . . as long as that’s the case, then studios don’t have to be too fussy about people coming and going,” said Prof. Weststar.

The Power of Publishers: Constant Growth and Crunch Culture

While employment structures might resemble creative industries, gaming is closer to tech in another way: growth. To Dianna Lora, large game companies seek constant and unsustainable growth, leading to games with production costs in the hundreds of millions of dollars. As production budgets increase, so too do the expectations associated with game performance.

As multiple developers told me, games can change quite heavily during the development cycle: new gameplay mechanics might be introduced, the art direction may evolve, and so on. But studios still have to meet deadlines. They may have made release date promises to fans, or want to capitalize on a major buying season like Christmas.

Enter large publishers. They may contract with studios to help fund game development, perhaps for a valuable IP that the publisher owns (like SpongeBob or Disney). With the funding comes strict production milestones. And when tight deadlines are added to evolving and unforeseen game direction, we get devs putting in crunch time to meet those milestones.

Take it from Prof. Weststar:

“The vast majority of people who make games are connected with this much more corporatized environment that involves publishers, venture capitalists, external funding agencies in various dimensions that then either directly contract a game, or the studio approaches the publisher for money and . . . help with marketing and assurances and things like that in exchange.”

“And then what the publisher does is it sets out very strict milestones throughout the course of the project, again to try to make sure it gets done when it needs to get done. So in theory, it’s not a bad thing, right? It’s not a bad thing to be like ‘check in every month and show us what you’ve done, OK?’ But then that also creates these mini crunch moments before each milestone.”

“[W]hat the publisher does is it sets out very strict milestones throughout the course of the project, again to try to make sure it gets done when it needs to get done . . . . But then that also creates these mini crunch moments before each milestone.”

Yet neither developers nor the studios they work for may have other options besides working under prestigious publishers’ schedules. According to Chris Soares, a digital artist with 30 years of game development experience, this is particularly salient when publishers or studios own popular brands and IPs (e.g., Star Wars or Marvel).

Chris told me how, years ago, a studio he was with was working on a Spiderman movie tie-in game. The publisher insisted the game be released the same date as the movie (for promotional purposes). So the devs had to crunch to make that deadline – to the point where the studio offered laundry services at the office so devs wouldn’t have to do it at home!