Corporate Landlords in Newark

David Hernandez

November 23, 2024

It’s no secret that the U.S. housing market has become increasingly inaccessible for the American working class. Even though popular media portrays homeownership as a cornerstone of American life, many have resigned themselves to the fact that buying a home will never be within reach.

The rental market holds equally grim prospects. Over half of all renters in the U.S. are rent-burdened, meaning they pay more than 30 percent of their income on rent and utilities each month. Half of those renters are severely rent-burdened, meaning they pay more than 50 percent of their income on rent and utilities each month.

With wages not keeping up with the cost of living and inflation, barring any government action, the result is inevitable. Homeownership is a mirage, and renting is financially disastrous for many. In no city is this truer than in Newark, New Jersey, where only 29.6 percent of housing units are owner-occupied, the lowest of any city in the country. In an opinion piece written by Newark’s own Mayor Ras J. Baraka, he laments that “Newark is leading the country in a category we desperately want to avoid.”

Increasingly, landlords in Newark are no longer people at all, but rather “faceless corporations and LLCs backed by private equity firms.” In 2022, Rutgers’s Center on Law, Inequality, and Metropolitan Equity (CLiME) released a bombshell report revealing a seismic shift in the city’s real estate ownership.

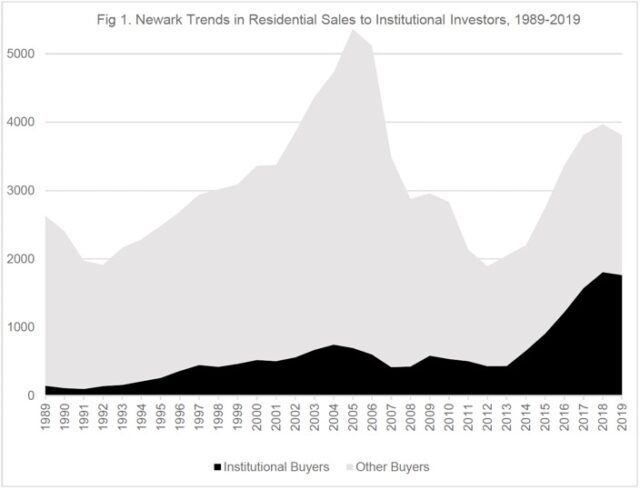

Fig. 1 from CLiME’s Who Owns Newark? Report

Since 2010, corporate landlords have tripled their share of residential property purchases from individual homeowners. As a result of their success, today, more than half of residential properties in Newark are owned by corporations.

Large companies have been assembling portfolios of single-family rentals at an alarming pace all across the country. Institutional buyers held a negligible number of single-family rentals at the beginning of 2012, but 100,000 by the end of 2013, and more than 700,000 by 2022.

They do so through a “combination of cash, speed, and scale.” For example, by acquiring properties directly from sellers before they have a chance to list it on a multiple listing service. Some have even bought directly from landlords exiting the business, thereby acquiring multiple properties at once, often at a discount. Others make all-cash offers with minimal contingencies in the hopes of securing the sale.

Photo by Chris Fry/Jersey Digs

To some, the unprecedented level of construction and investment in the city is an indicator of prosperity. Glass towers now dot the Newark skyline with more frequency, with others such as the Halo project soon to come. The promise of an increased tax base is appealing, especially for a city struggling to pave a path forward.

Others are less optimistic. The future of Newark may be bright, but it’s not clear that its residents will be the ones to benefit most from the rising tide. This rapid transfer of land from individuals to institutional buyers resulted in homeownership rates declining more than 6 percent from 2010 to 2020 in the city’s West and South Wards, where nearly three-quarters of institutional purchases took place, according to the CLiME report.

Being the most renter-dominated housing market in the country, it makes sense that Newarkers aren’t up in arms over the plight of individual landlords who seem relatively well off. But this shift towards corporate landlords may have spillover effects for all the city’s residents, renters included. One study of buy-to-rent investors in Georgia found that “over the next year, properties within a quarter mile of a buy-to-rent purchase appreciated by … 3.4 percent more than properties located 5-10 miles away.”

Are corporate landlords any different?

Landlords generally aren’t known for being the most generous individuals. So, it’s fair to ask, is this corporate takeover in real estate even something to be concerned about? On the contrary, might this even be an improvement over the status quo?

The housing crisis requires a large investment in the supply of housing units, ideally as high-density development since the space inefficiency of single-family homes makes meeting the demand for housing that much harder. Corporations are better positioned relative to individual landlords to access capital at a lower cost, whether that be for repairs, rehabilitations, or new construction projects.

And, in the abstract, it’s possible that by operating within larger economies of scale, corporate landlords can minimize overhead costs for large real estate portfolios to make room for profit without reducing the quality of housing or the quality of life of their tenants. Unfortunately, the research shows there are good reasons for Newarkers to be concerned about the transition to corporate landlords.

One study in the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s Cityscape journal found that large corporate landlords were “68 percent more likely than small landlords to file eviction notices even after controlling for past foreclosure status, property characteristics, tenant characteristics, and neighborhood.”

Another study in the Social Forces journal was based on over 4 million property tax records and 15 years of eviction records in Boston and found that large landlords file for eviction at two or three times the rate of small landlords, even when controlled for tenant characteristics.

Even more telling, when a property is sold from a small-scale landlord to a large-scale landlord, “[eviction] filing rates immediately and permanently increase, and there is a particularly large spike in filings during the sale year, almost entirely attributable to the new large-scale owners.” These landlords tend to file for evictions over less money owed and more often as a rent collection strategy.

As to why that is, the study suggests that for large-scale landlords, evictions have become “a routine business practice” that is “accompanied by little fanfare,” whereas small landlords have “personal relationships with tenants [that] make eviction a morally fraught decision.” In other words, the moral distance offered by the corporate form makes the prospect of filing for eviction in the name of profit more palatable for investors who may not have had the stomach to do so individually. In contrast, individual landlords tend to be more responsive to reputational incentives and the relationships they develop with their tenants when compared to their corporate counterparts.

To make matters worse, much of this activity has been concentrated in low-income neighborhoods, where renting is most profitable. In Milwaukee, a $40,000 single-family home was found to be just 10 percent cheaper to rent than an $80,000 single-family home. In Do the Poor Pay More for Housing?, Matthew Desmond’s research found that landlords in Milwaukee’s high-poverty neighborhoods recover their investments more than twice as fast as those in low-poverty neighborhoods. It would take landlords in low-poverty neighborhoods approximately ten years to recover the total value of the property through rents, whereas in high-poverty neighborhoods that time horizon is just four years.

Rent-Setting Algorithms

Increasingly, corporate landlords are more likely to enlist rent-setting algorithms to price their units for lease renewals and new renters. Property managers then get the benefit of distancing themselves from the resulting rent hikes and tenant turnover while continuing to squeeze as much as possible out of the tenants who can afford to stay year after year.

Attorneys general in Arizona and Washington D.C. recently sued an algorithm developer known as RealPage, along with more than a dozen of its landlord clients, for violating antitrust laws. They claim that by offering a shared platform for competing landlords, RealPage is effectively operating as an illegal rent-setting cartel. This wave of lawsuits was kickstarted in part by a ProPublica investigation, describing the significant role that RealPage played in facilitating rent hikes on behalf of property managers.

At a Tennessee real estate convention, RealPage executive Andrew Bowen stated that “[a]s a property manager, very few of us would be willing to actually raise rents double digits within a single month by doing it manually.” In a testimonial video, one property manager stated that the beauty of RealPage “is that it pushes you to go places that you wouldn’t have gone if you weren’t using it.”

The software’s recommended rent hikes allow property managers to be more comfortable with longer unit vacancy periods. Unfortunately, this further reduces the supply of housing and exerts upward pressure on rents despite the existing housing shortage. In New Jersey, where the state is suffering from a shortage of almost 300,000 affordable housing units, it’s profitable for landlords to play the waiting game until prospective tenants give in to the higher posted rents.

“is that it pushes you to go places that you wouldn’t have gone if you weren’t using it.”

RealPage has seen widespread adoption by property managers. By the end of 2020, RealPage’s Securities and Exchange Commission filings stated their services and products were used to manage 19.7 million rental units. Looking specifically at Seattle, ProPublica found that “70% of apartments were overseen by just 10 property managers, every single one of which used pricing software sold by RealPage.”

Newarkers are already keenly aware of the harm this has done in other cities and are wary of outside investors. A recent petition drafted by Parents Educating Parents asks legislators to regulate rent algorithms, requiring more transparency in how rents are calculated and guarding against collusion, discrimination, and exploitation.

My Own Experience Renting in Newark

Being born and raised in Newark myself, my own experience aligns with the data. I can’t help but wonder whether my life might have looked very different had I lived under a corporate landlord. I offer the following personal contribution as but one data point that hopefully brings some texture and an element of human complexity to the conversation.

After years of bouncing around from one apartment to another, in 2011 my family found a modest second story walk-up in the city’s North Ward. The landlord was a pastor named Elvis who lived on the first floor with his family. Most importantly, my mom could afford the rent.

Our time in that apartment was far from perfect. The roof leaked constantly, and I would sometimes wake up to falling wet debris after a particularly rainy night. Reliable hot water was an issue. Each time we ran into problems, Elvis tried to make the repairs himself to save on costs. Each time the patchwork failed, we patiently relayed the issue back to him. It was a cycle of frustration, made worse by the knowledge that we had few, if any, other options.

And yet, we were lucky. Elvis always had our back. He often made the time to listen. When we needed to haul a piece of furniture up the stairs, he never failed to offer a helping hand, even if he was just coming home from work. When making repairs, he would take the time to teach me a thing or two about working with tools.

To me, what was most surprising about Elvis was the way he dealt with us. A few years into our stay, when my mom separated from her then-partner, he lowered our rent, acknowledging that my mom had a lot on her plate with two kids to raise on one cashier’s salary. We lived in that apartment for almost a decade. Not once did Elvis ever raise our rent.

This would be inconceivable under a corporate landlord. A corporation would not care about our financial circumstances. Their algorithmic rent calculator might have encouraged increases in rent to outpace the market month after month. The property manager would have blindly followed the recommendations. They wouldn’t have looked past late payments. They wouldn’t have given us grace. We almost certainly would have been evicted.

Thankfully, Elvis practiced what he preached. He showed us compassion. He saw us as people and not just tenants. He dealt with us fairly, not with only profit in mind.

As a result, my years as a high school student were some of the most stable in my life. I went to Science Park High School for four years, my longest consecutive stint at one school thanks to not having to constantly move around anymore. I became the first in my family to graduate high school and was offered a full ride to attend Harvard College which I gratefully accepted.

After graduating and finding a decent-paying job with the Robin Hood Foundation, my mom and I were able to scrounge up enough funds to put a downpayment on a home, achieving a lifelong dream. I can’t help but credit Elvis’s kindness and support for allowing us to remain stable long enough to become homeowners.

To be clear, my point in bringing up my family’s almost decade-long relationship with Elvis is not to argue that he exemplifies all landlords or that individual landlords can’t be just as extractive and apathetic as corporate landlords. Instead, I aim to highlight the kind of individual connection, compassion, and empathy which would be virtually impossible to replicate under a corporate landlord who distantly manages their properties according to a strict profit motive.

In a city that is transitioning more towards corporate landlords, I fear we may be losing something along the way.

Legal Empowerment and Disempowerment

Going back to Who Owns Newark?, the report makes clear that while investor activity may appear troubling to the city’s residents given the threat of rapidly rising rents, decreased homeownership rates, and renter displacement, real estate investing is a constitutionally protected activity. They make no allegations of wrongdoing given that no illegal activity was detected on the part of investors.

One interpretation of this conclusion is that no harm was done and that we are all better off because of investor activity. Another interpretation is that our political and legal systems have failed to adequately protect the interests of Newark’s residents in the face of investor activity.

If corporations are uniquely advantaged by their corporate form, it is only with permission and support from the state. State and local laws, or a lack thereof, play an important role in empowering corporations to extract value from vulnerable communities.

For example, a lack of state and local laws mandating public disclosure of investor principals allow institutional buyers to speculate in the residential real estate market in Newark with almost complete anonymity. Investors often operate under several layers of shell corporations disguising themselves. The result is an information asymmetry which is ripe for abuse.

In practice, individual homeowners might sell their land at a bargain to an outside developer with the funds to pay more. A neighborhood of home sellers may be under the impression that they were selling their homes to different buyers, only to later realize they were all shell companies for the same entity. This shell game artificially reduces the power of sellers to claim the value from rising land values, as has been the case in Newark.

Thankfully, our state and local laws may also play a role in disempowering corporations to protect other important stakeholders in the community such as working-class families.

![[F]law School Episode 7: Profit Over People](https://theflaw.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/Housing-Podcast-Episode-hero-image-640x427.webp)