Maria’s life as an environmental activist begins in 2007 when a friend from Abruzzo calls her. During this call, Maria, freshly appointed a professor at the age of 34, learns about rumors of a new fossil fuel project off the coast of Abruzzo. Knowing about the fragility of the coast, she is convinced that any such project would not only delay the necessary phase-out of fossil fuels but also pose a great danger to fishing, agriculture, and tourism in the region. When Maria’s friend notices her discomfort, he tells her:

“Don’t worry. There is nothing you can do about it.”

But Maria, determined to act, decides against her friend’s well-meant advice.

During that year’s winter break, Maria travels to Abruzzo to see her mother. Yet, Christmas is not the only reason for her visit. After countless unsuccessful attempts to reach out to politicians, journalists, academics, environmental NGOs, and even the church while based in California, Maria wants to seize the opportunity and raise awareness for the perils of the planned fossil fuel project. After the turn of the year, she begins to tour Abruzzo to educate the local community about the project and present the troubling results of her research. Around the same time, drilling rigs pop up off the coast of Abruzzo to explore Ombrina Mare, an offshore oil field holding around 166 million barrels of crude oil. Assunta Di Florio, a teacher at a local school, remembers these days vividly:

“Me and the kids of my school saw, from the window of our school, the Ombrina Mare platform emerging. We looked into the project and then contacted the mayor and other politicians to find out more. Then we collected signatures and joined the demonstrations and protests.”

Unnoticed by the local community, the project has been approved for exploration. But, as it turns out, the owner of the exploration permit, the UK-based fossil fuel company Mediterranean Oil & Gas PLC, has underestimated the resistance of the local community. With the help of others, Maria brings together civil society actors from all across the board, creating the No Ombrina Movement. Fishermen, trade unions, students, bishops, and many more unite to mobilize against the exploration and exploitation of the Ombrina Mare oil field.

A No Ombrina protest in Lanciano, Abruzzo, Italy.

Not long after its formation, the movement achieves its first success. In March 2008, the local government succumbs to the pressure of the No Ombrina Movement and puts a moratorium on the construction of a nearby onshore refinery associated with the Ombrina Mare project. This moratorium is later extended. However, it does not affect the exploration and exploitation of the Ombrina Mare oil field itself, which is subject to central decision-making. Only two years after the establishment of the local moratorium, against the backdrop of the disastrous Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico, Rome enacts a legislative decree banning fossil fuel exploration and production within five miles of the Italian coast.

But the impression of Deepwater Horizon does not last. Just two years after the ban’s establishment under Silvio Berlusconi, the decree – a thorn in the side of Italy’s influential oil and gas lobby – is modified by his successor Mario Monti in an attempt to attract as much as $18 billion in investments. This modification is devious: While it extends the decree’s scope of application from five to twelve miles, it also introduces a so-called grandfathering clause exempting existing oil projects from the ban. According to Maria:

“This was a complete ruse because there was almost no portion of the Italian coastline that had not been leased out to oil companies. So effectively, the new ban applied to a minuscule part of the Italian coastline.”

Shortly after, planning for the permanent extraction of oil from the Ombrina Mare oil field resumes, and so do the protests. In April 2013, a record-breaking 40,000 protestors gather in Pescara, a small city on the coast of Abruzzo. Two years later, following the controversial approval of the project’s environmental impact assessment by the Italian Ministry of the Environment, more than 60,000 march through Lanciano, a sleepy town with a population of just 35,000.

“Don’t worry. There is nothing you can do about it.”

For some time, it looks like all organizing is pointless and the final production permit will be granted against all resistance. But, just as the Italian Ministry for Economic Development is about to issue the production permit, the Italian parliament steps in. In December 2015, it responds to the call of the No Ombrina Movement and approves a law reestablishing the 2010 ban on fossil fuel exploration and production within twelve miles of the Italian coast. After eight years of fighting against the Ombrina Mare project, Maria has finally reached her goal.

All is well that ends well.

Maria D’Orsogna celebrating with friends.

But Maria’s story does not end yet.

The Ace up Rockhopper’s Sleeve

Rockhopper Exploration PLC, another UK-based fossil fuel company that has acquired the former license holder Mediterranean Oil & Gas PLC in the meantime, has an ace up its sleeve. In March 2017, Rockhopper publishes a press statement quoting its CEO Sam Moody:

“Whilst we had hoped to avoid arbitration, we are extremely disappointed that it has proved to be necessary in order to protect our investment in the Ombrina Mare project. While it may take some time to produce a result, and there is no certainty of success, Rockhopper is taking all necessary steps to protect its shareholders’ interests at no extra cost to the Company.”

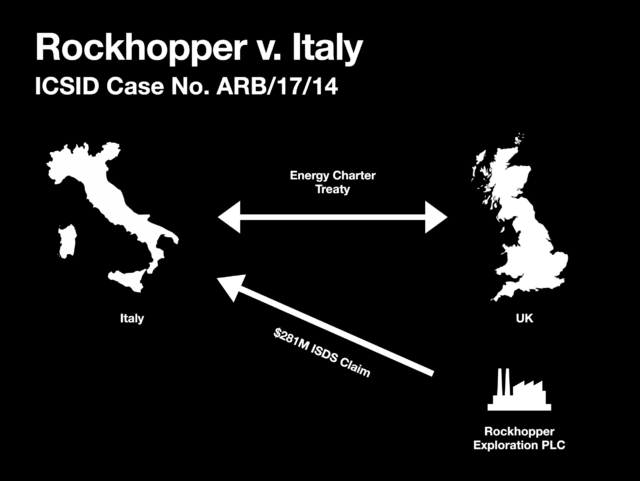

This ace is the arbitration clause of the Energy Charter Treaty (ECT), a notorious international investment agreement (IIA), to which both the UK and Italy are parties.

“Italy owes no compensation for the incidental inconvenience caused by its regulatory measures of general application.”

IIAs are international agreements between two or more states through which these states make a mutual commitment to protect investments by nationals of the respective other states (foreign investors). This protection typically encompasses an obligation to fair and equitable treatment and a prohibition of unlawful expropriation. Today, there are over 3000 such agreements worldwide. What is most important about IIAs, however, is the fact that they typically empower foreign investors to directly claim compensation for breaches by the host state before an international arbitration tribunal. Such a tribunal, normally a panel of three arbitrators constituted ad hoc to decide a particular dispute, then issues a globally enforceable arbitration award. This mechanism is called investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS).

Making use of this mechanism in the ECT, Rockhopper sues Italy for a whopping $281 million of compensation for stranded assets and lost profit. Rockhopper argues that the final denial of the production permit as a consequence of the ban on offshore drilling constituted an unlawful expropriation under the ECT. Italy defends itself by pointing out that the ban “constituted a legitimate exercise of police powers” with “the goal of adopting a cautionary approach to the protection of the environment, prohibiting new extractions in the sensitive areas close to the coasts and the protected zone”, thus “averting the […] view that its acts constituted [an] unlawful expropriation.”

“Italy owes no compensation for the incidental inconvenience caused by its regulatory measures of general application.”

Italy’s argument hinges on the unwritten police powers doctrine, according to which general regulatory measures are precluded from being characterized as expropriating when taken in good faith, for a public purpose, in a way proportional to that purpose, and in a non-discriminatory manner.

Slide designed by Sven Siebrecht.

After years of proceedings, in August 2022, the established arbitration tribunal awards Rockhopper $190 million without paying much attention to Italy’s argument. While the tribunal feels the initial need to stress that it “appreciates and is acutely sensitive to the fact that there are strongly-held environmental, civic and political views about offshore production in Ombrina Mare” and that “the outcome of this case passes no judgment whatsoever on the legitimacy or validity of those views”, it is quick to dismiss Italy’s defense on the merits.

Arguing on a textual basis, the tribunal simply finds that it is “not persuaded by the […] invocation of police powers” as “for a sovereign to avoid the consequence of unlawful expropriation it must cumulatively satisfy all of the requirements […] of the ECT.” Effectively, the tribunal denies the existence of a State’s right to regulate under the ECT beyond its written exceptions. At the same time, the award reveals that the tribunal perceives its ability to act as limited because the ECT does not contain any explicit carve-outs for domestic regulation that would allow for a measure like the established ban on offshore drilling.

So no happy ending after all? We will have to wait and see. Currently, Italy is proceeding for an annulment of the award. The grounds for Italy’s application for annulment are not public.

An Epitome of a Larger Problem

Unfortunately, Rockhopper v. Italy is not the only case in which domestic climate regulation has been thwarted by foreign fossil fuel investors through ISDS proceedings. In 2017, for example, Nicolas Hulot, then French Minister of the Environment, found himself in a similar situation. Hulot had just assumed office and had announced his plan to end all fossil fuel extraction on French territory by 2040. But Vermilion Energy, a Canada-based fossil fuel company and France’s largest onshore oil producer, had other plans for the so-called Hulot law. In a letter to the Council of State, France’s supreme administrative court and legal advisor to the government, Vermilion’s lawyers meticulously laid out why they thought the Hulot law violated the ECT and how its enactment would leave Vermilion no other choice than to sue France in front of an ECT arbitration tribunal.

The Council of State intervened. When the Hulot law was finally enacted, it allowed existing fossil fuel producers to indefinitely renew their concessions until 2040, and in some cases even further. Frustrated by this experience, Hulot resigned only one year later, partly blaming the power of lobbies in French politics.

Image taken by COP Paris and provided by Wikimedia under a Creative Commons License.

Examples of the strategic use of ISDS mechanisms by corporate investors are not limited to the ECT. The Red Carpet Courts project has compiled ten cases that illustrate the strategic use of ISDS provisions by large corporate players. In a similar vein, David Boyd, then the UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights and the Environment, has published a list of ISDS claims launched in response to climate action.

Hardly surprising, the potential of weaponizing ISDS provisions against climate action has not remained unnoticed by major law firms either. Jones Day, for example points out the importance of strategic restructuring in a newsletter from March 2022:

“Companies in industries most affected by States’ climate change obligations (e.g., fossil fuels, mining, etc.) should audit their corporate structure and change it, if needed, to ensure they are protected by an investment treaty. Such restructuring should take place before any climate-related dispute with the State has arisen or is reasonably foreseeable. Notably, some treaties have superior investor protections than others. It is thus important to assess which treaty would best protect the company from any adverse climate-related government measures.”

What Jones Day is saying here is that fossil fuel companies should make sure to structure their assets in a way that allows them to make use of IIAs with particularly weak regulatory carve-outs when they face restrictive domestic climate policies.

The Narrative of the Vulnerable Investor

In Jones Day’s newsletter but also more generally, IIAs are characterized by the narrative of the vulnerable investor that has to be protected from arbitrary state encroachment. That said, the idea behind ISDS is not wrong per se. Empowering individuals vis-à-vis states is a mechanism that has proven its efficacy in the field of human rights law. As such, it carries the potential to enhance compliance with international law and thus contribute to the pacification of international relations. The flaw of many IIAs, however, is their lack of regulatory carve-outs that safeguard a state’s right to regulate for a public purpose. As a result, some IIAs grant nearly all-encompassing protection for investors.

This flaw in the design of IIAs has to be viewed against the backdrop of the history of modern IIAs. The broad majority of the more than 3000 IIAs has been signed since the 1990s. A key reason for this proliferation of investment treaties in the post-Cold War era was the victory of market ideology that had been epitomized by the collapse of the Soviet Union.

The ECT serves as a good example in this regard. Signed in 1994, the ECT captured the gold-rush atmosphere of the 1990s when the collapse of the Soviet Union opened up ample investment opportunities in the East. Europe’s growing energy demand and the vast availability of energy resources in post-Soviet states seemed like a great match. However, European investors also feared arbitrary governments. As a result, regulatory carve-outs were perceived as loopholes that could lend host states legal arguments to defend their arbitrary treatment of investors.