Victims in Court

Terrence Collingsworth—the director of International Rights Advocates and an attorney who has spent his career advocating for victims of corporate abuses—believes corporations are not exempt from scrutiny for their role in these tragedies. Collingsworth is currently representing a group of Yemeni victims as they bring suit against the US government and several US weapons manufacturers after suffering injury or the death of their loved ones in Coalition airstrikes.

While the plaintiffs call for accountability within the margins of a 100-page legal complaint, their experiences of loss and suffering are altogether too big for any format. Some of the plaintiffs experienced the horror of a small-town wedding party turned into the target of, not one, but two missile attacks. The family of the groom who died in the attack recalled that, in the aftermath of the explosion, they “could only recognize him through his wedding ring, which had his wife’s name etched on it.”

Other plaintiffs were paying their respects at the funeral of a community member when the venue was struck by two missiles. Dozens of innocents lost their lives in the attack, but the survivors of the massacre live on “in a permanent state of stress.” “This situation still haunts me throughout my sleep,” said one victim of the attack.

Photo taken by Khaled Abdullah from Reuters

The attacks—both on obviously civilian gatherings—together killed an estimated 189 people and injured 675 more. Those who survived refuse to enable the impunity of the actors who harmed them and thousands of others in Yemen. Their contention: Corporate arms manufacturers are lining their pockets, but they cannot escape accountability for the harm they have caused.

The Alien Tort Statute: A Tool for Accountability…

The primary claims in the lawsuit (Ali v Al-Nahyan) against the defendant corporations—Raytheon, Lockheed Martin, and General Dynamics— are brought in part under the Alien Tort Statute (ATS). The ATS, an unassuming provision enacted by the first Congress in 1789, comprises just thirty-three words. Yet, the statute, which “speaks in terse, open-ended, and somewhat cryptic language,” became a battleground for human rights litigation only in recent decades.

The ATS gives US courts jurisdiction over a “civil action by an alien for a tort only, committed in violation of the law of nations or a treaty of the United States.” The statute empowers non-Americans to sue for civil remedies when they are the victim of a violation of internationally-recognized standards, such as the prohibition of slavery.

The relative ambiguity and breadth of the text suggests the potential power of the statute as a legal tool. The law seems to allow the victims of human rights abuses to sue their offenders, with no clear restrictions. Yet, litigators did not discover the utility of the ATS for this type of work until the 1980s, after the groundbreaking outcome in Filartiga v. Peña-Irala.

The Supreme Court “grafted onto [the ATS] this extremely unclear, burdensome and vague new standard that didn’t exist.

In Filartiga, the court awarded over $10 million in damages to the family of a child who was tortured to death by a former Paraguayan official. The outcome grabbed the attention of litigators. Here, the court allowed the case to be heard when neither of the parties were Americans and the alleged abuse had occurred outside of the US. Rarely are courts willing to deal with a case that does not, in some way, fall within the US’s territorial borders.

In Filartiga footsteps, lawyers began bringing cases against corporations on behalf of the victims of heinous crimes either committed or aided by the corporations. Though early cases saw some success for victims, usually in the form of a settlement between the parties, the period proved short where the ATS was a promising tool to deliver accountability for the international human rights abuses of corporate actors.

…Or a Door Closing?

In response to the potential threat of ATS lawsuits, corporations began working behind the scenes to whittle away at the statute. Despite the broad scope of the ATS’s text, Collingsworth explained that corporations have been able to put pressure on courts to interpret the statute narrowly. The Supreme Court “grafted onto [the ATS] this extremely unclear, burdensome and vague new standard that didn’t exist. So, though [the Supreme Court] in cases have textual interpretations that they boast about, they threw that out the window when corporate America came calling and said ‘we want you to fix this’,” said Collingsworth. These new standards mentioned by Collingsworth have proliferated over time, narrowing the ATS by limiting the law’s application when the conduct at issue in the case occurs outside the US or when the case is brought against foreign corporations.

The Supreme Court delivered the first of these blows to the ATS in Kiobel v. Royal Dutch Petroleum Co. Decided in 2013, the Court determined that the claims must “touch and concern” the territory of the United States to the extent that it “displace[s] the presumption against extraterritorial application.” Essentially, after this case, the conduct in subsequent cases would have to be sufficiently tied to the US to be heard by the court—a restriction never mentioned in the ATS itself. Then, in 2018, the Court’s decision in Jesner v. Arab Bank further narrowed the ATS by precluding ATS suits against foreign corporations.

Collingsworth saw the Supreme Court’s most recent decision on the ATS in Doe v. Nestle as effectively “gutting” the ATS. In Doe v. Nestle—a case filed by Collingsworth and decided by the Supreme Court in 2021—the Court again favored a narrow interpretation of the ATS. There, victims of child slavery on cocoa farms in the Ivory Coast sued Nestle and Cargill for aiding and abetting the abuses. While the Court found that the defendants “did buy cocoa from farms located [in Ivory Coast]” and “provided those farms with technical and financial resources—such as training, fertilizer, tools, and cash—in exchange for the exclusive right to purchase cocoa,” the Court anomalously concluded that “[n]early all the conduct” that was relevant to the case had occurred abroad. Even though the defendant corporations made the “operational decisions” in the US, the Court held that this level of domestic activity was not enough for the Court to decide the case.

Photo of supreme court licensed under the creative commons attribution-share alike 4.0 international license

“The fairly extreme test” applied by the Court, according to Collingsworth, seemed to mark the end of ATS suits. The Court’s bar appeared so high in the wake of the decision that “we [ATS litigators] sort of joke, but it’s probably true, that Nestle and Cargill would have had to have kidnapped children from, like, New Jersey and took them to Cote d’Ivoire and enslave them before this Supreme Court would say that the statute applied,” said Collingsworth. “It was definitely a great concern of mine as to whether there’s any life left in the ATS.”

Judicial Reasoning and Corporate Power

The pressure from corporate interests to shut down the ATS is clear. During Collingsworth’s career, he’s witnessed the influence that corporate America can exert on the outcomes of corporate accountability cases. One form of this influence is through amicus briefs, or briefs filed by non-parties to the case. “[H]aving the US Chamber of Commerce, the National Association of Manufacturers, and giant corporations like Chevron filing amicus briefs is a direct communication . . . [T]hey can afford to intervene in any case that they perceive as being against the interests of corporate America, and they do that regularly and quite successfully,” said Collingsworth. In the Kiobel case, for example, more than 30 briefs were filed in support of the corporate defendant.

But these aren’t the only channels corporations can use to influence the judicial process. “Level 2 is just the stranglehold that these giant law firms have on the development of the law,” said Collingsworth. “Most of the Supreme Court clerks and most of the Appellate clerks that come out of our system, they go to work for [big law firms]…that represent corporate America,” explained Collingsworth. This type of training creates systemic biases in the courts because “there’s no rule against a former clerk for [a Justice] arguing a case on behalf of corporate America in front of the Supreme Court. There’s no rule against any of them arguing cases that are before the judges that they once worked for,” said Collingsworth.

Together, these different levels of influence work to imperceptibly guide the Court to decisions that are, it seems, more akin to the reasoning espoused by corporate interests than judicial reasoning.

A Window of Hope for the ATS

With all of the ATS’s baggage, it is a wonder why ATS litigators like Collingsworth continue to sue under the ATS. The reason is actually quite simple: “There are very few other options that I have . . . corporate America has made it or tried to make it almost impossible to hold them accountable for their international human rights crimes,” said Collingsworth.

While the ATS is no longer the robust statute that litigators once hoped it could be, there is still reason to believe that particular ATS suits—like Collingsworth’s current case, Ali v. Al-Nahyan—can successfully go forward. In a recent case decided by the Ninth Circuit, Doe I. v. Cisco Systems, Inc., the court gave the green light to a group of Chinese plaintiffs who claimed that Cisco Systems aided and abetted human rights violations committed by the People’s Republic of China. Specifically, Cisco designed and built the surveillance system that China used to identify its victims.

According to Collingsworth, these facts, which mirror the facts of Ali v. Al-Nahyan, appear to fit through the narrow window left for ATS suits. Cisco is a US company and it built and designed the surveillance system for China in the US. Collingsworth believes that, if these facts meet the threshold for ATS cases after Nestle, then certainly the claims against US arms companies in Ali v. Al-Nahyan should go forward. “In this case, General Dynamics, Lockheed, and Raytheon… they built the weapons. They designed them here. All the parts are from here,” argues Collingsworth. Under this formula, there’s hope that this type of case will clear the hurdles put in place by the Supreme Court on the ATS’s application.

Government Contractor Defenses

However, in response to aiding and abetting claims, companies serving as government contractors can avail themselves of legal defenses based on their relationship with the government. Essentially, as companies in the defense industry could argue, the US government authorizes foreign military sales to foreign governments, while the arms companies are simply providing the weapons as one step in the process. The companies are not named as the actors authorizing the transfers, nor the actors responsible for ensuring that the foreign military sales are used in a particular way. As these companies would argue, for the judicial branch to question their role in this process, it would actually be questioning the decisions of the executive and their foreign policy strategy—something beyond the judicial branch’s reach.

Formally, these types of arguments can all be considered different forms of a “political question” argument. “Political questions” are issues that go to the heart of another branch’s decision-making. Courts decline to hear these matters so as to avoid constitutional separation of powers concerns.

In a case like Ali v. Al-Nahyan, arms companies argue that courts cannot scrutinize the executive branch’s decisions to sell weapons to foreign nations, which are made pursuant to the Arms Export Control Act (AECA) and the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961 (FAA). The AECA and the FAA empower the executive branch to make defense sales, or license private companies to sell, to foreign nations “in furtherance of world peace and the security and foreign policy of the United States.” The statutes show deference to the President’s assessment of the foreign policy and national security interests of the United States.

Screenshot of the FAA

But the executive’s discretion is not unrestricted. The statutes themselves restrict assistance to countries with a “consistent pattern of gross violations of internationally recognized human rights” and require that the US monitor the use of its weapons to ensure that they are not used in violation of international law.

Yet, the US Government has asserted against a challenge to their continued provision of FMS to the Saudi-led Coalition, despite a surplus of documentation of the Coalition’s violations of international law, that their decision to provide assistance is unreviewable.

“The untenable position of the [US Government] is that they have complete and total discretion to approve arms sales to anyone, anywhere, with no possibility of judicial review. This is simply not the law; and the mere prospect of giving total discretion to the Executive Branch to distribute lethal weapons around the world at will is terrifying,” states Collingsworth’s legal opposition to the federal government.

Even if, as Collingsworth asserts, the government’s discretion is reviewable, the weapons manufacturers claim that their role in this process is not. They are just doing what the government authorizes, right?

In the US Government we Trust

Business for Lockheed Martin, Raytheon, and General Dynamics during the Coalition war in Yemen was good. When the war in Yemen started in 2015, Raytheon’s stock was selling for $108.44 per share. By 2018, the share price had risen to $210.70. As Raytheon’s CEO said to investors in a 2022 conference call, “peace is not going to break out in the Middle East anytime soon. I think it remains an area where we’ll continue to see solid growth.”

Yet, shareholders were not unaware of, nor unconcerned with, the devastating impact of the corporations’ sales practices. At the 2021 Lockheed Martin annual shareholder meeting, a shareholder proposal was put forward which would require the company to “identify, assess, prevent, mitigate, and remedy actual and potential human rights impacts” of its “high-risk products.” At General Dynamics’s annual shareholder meeting in 2022, shareholders made a similar proposal, citing evidence of General Dynamics’s weapons used in war crimes by the Coalition in Yemen and by Israeli Defense Forces against Palestinians.

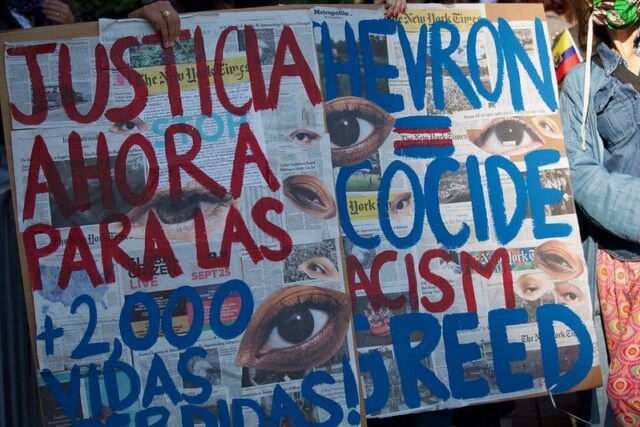

A picture of a piece of a Raytheon bomb by Mwatana for Human Rights

The General Dynamics Board of Directors unanimously voted against the shareholder proposal, noting that it would “undermine shareholder value.” Regarding the company’s approach to human rights, the Board stated that their “North Star is the law and policy of the U.S. Government” and that adopting internal human rights due diligence policies would “put[] the company and its largest customer at odds.”

This attitude is standard across arms companies. In 2019, Amnesty International contacted 22 arms companies asking them to elaborate on how they ensure that their products are used in compliance with international law. None of the companies that responded could articulate how they meet international human rights standards or demonstrate that they conduct any serious human rights due diligence. Fourteen of the companies didn’t respond.

“There’s a huge lack of transparency in terms of what their actual policies and processes are,” said Patrick Wilcken, an Amnesty International researcher whose work covers human rights in relation to arms trade. But the trend amongst US arms companies is “sticking to the line that it’s the US government’s responsibility and that they are merely servicing government contracts,” said Wilcken.

But in terms of developing human rights standards in international law, companies themselves have a responsibility to undertake human rights due diligence. Since the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs) was endorsed by the UN Human Rights Council in 2011 “there has been more than ten years of consolidation of the norms . . . these norms are well established, well recognized, both across corporate and government spheres,” said Wilcken. “There’s no reason why the arms industry should be excluded from the developments in this field.”

While the arms companies claim that they rely on the US government to conduct all necessary vetting processes for sales to foreign nations, the concerns of their own shareholders, and the criticism facing the US government for its policies, lays bare the incoherency of this explanation. How can arms companies claim that they are meeting their responsibilities simply by trusting the government’s decision-making when they face clear and consistent evidence that their weapons are not in fact used appropriately? “Hiding behind governments is not good enough – especially when license decisions have been shown to be flawed,” notes Wilcken.

The successful implementation of this type of finger-pointing as a corporate defense in court results in a kind of “liability laundering.” Because the government enjoys various protections from legal accountability, like sovereign immunity or the political question doctrine, plaintiffs injured by the government’s decisions face an enormous hurtle to exact accountability. But, even when the government, as it often does, outsources its functions to private entities, corporations argue that they fall under the government’s umbrella of protections for their actions, too. As a result, a wide range of activities that normally would be susceptible to remedies can create victims with no accountable defendant.

With this much business potentially protected from legal accountability, there’s no wonder arms companies are calling the US government their North Star.

Not your Average Government Contractors

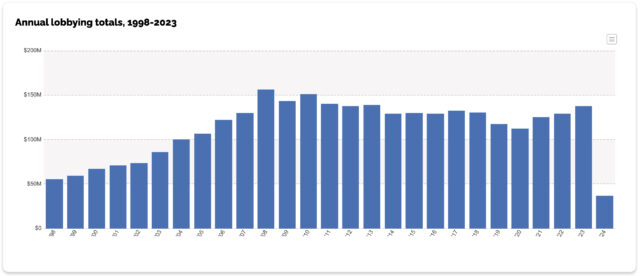

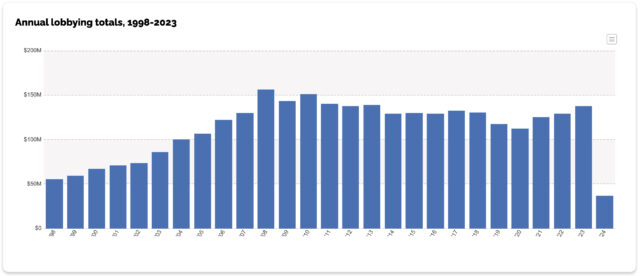

In fact, there’s ample reason not only to believe that arms companies are negligently shirking their responsibilities by not conducting their own due diligence, but that arms companies actively encourage dangerous US foreign policy. Since the early 2000s, annual lobbying expenditures by the defense industry have consistently surpassed $125 million—totaling about $2.5 billion over that period. While claiming to be at the whim of US policy, the defense industry spent almost $300 million over the same period on campaign contributions to Congressmembers and employed about 700 lobbyists every year.

Arms companies took their lobbying efforts to another level to overcome opposition in Congress against weapons sales during the war in Yemen. Between 2015 and 2021, the DOD provided $54.6 billion in military support to Saudi Arabia and the UAE. Yet, Congressional discontent with the Saudi regime over its actions in Yemen and later with the assassination of Jamal Khashoggi culminated in several congressional initiatives aiming to block arms sales to Saudi Arabia. Reporting at this time revealed the aggressive lobbying efforts of arms companies, like Raytheon, to build opposition to the bills.

Graph from Open Secrets of lobbying totals by defense industry

The lobbying efforts aimed to persuade from every possible direction. After Congressional pressure calling on the State Department to review Saudi Arabia’s record on civilian protection, Charles Faulkner, a former Raytheon lobbyist who was serving as the State Department’s head of the Bureau of Legislative Affairs, intervened. He led an ultimately successful advocacy campaign at the State Department to certify Saudi Arabia as a US-weapons recipient, arguing explicitly that “lack of certification will negatively impact pending arms sales.”

President Trump himself promoted the economic benefits of the military-industrial complex, using his “Buy American” policy to roll back regulations on weapons sales and encourage more arms deals.

Investigative journalism also revealed significant lobbying by Raytheon of Mr. Peter Navarro, President Trump’s trade advisor who openly advocated weapons sales as an economic growth strategy. One instance of these efforts involved a lunch meeting arranged between Navarro and the heads of several defense companies, including Thomas A. Kennedy, then Raytheon’s chief executive. Navarro was apparently deeply influenced by his connections with the arms industry. In 2017, after consulting with industry executives, Navarro wrote a memo calling on Trump to intervene against Sen. Bob Corker’s move to halt arms sales to Saudi Arabia. The memo was entitled “Trump Mideast arms sales deal in extreme jeopardy, job losses imminent.”

Lobbyists frequently tout the promise of jobs from weapons production and sales to congressmembers. President Trump himself promoted the economic benefits of the military-industrial complex, using his “Buy American” policy to roll back regulations on weapons sales and encourage more arms deals. In one instance, Trump claimed that 500,000 US jobs would come from arms sales to Saudi Arabia, although estimates actually put the figure at 10 to 20 times lower.

“You don’t want to be seen as opposing something that creates jobs in your state,” said William Hartung, an expert on the arms industry at the Quincy Institute . Hartung notes that, in reality, though, spending on weapons creates 40 percent fewer jobs than spending on infrastructure, and 100 percent fewer jobs than spending on education.

To a large extent, the American public is unaware of lobbyists’ activities. “There could be a lot more transparency about what the lobbyists are up to,” said Hartung. Hartung explained that, while there are restrictions on foreign lobbyists, and some restrictions on domestic lobbyists, the regulations are a “patchwork.” “People will say ‘I give strategic advice, I don’t lobby,’” explained Hartung, which allows people to avoid the minimal regulations that do exist for a registered “lobbyist.”

The role of the revolving door is perhaps one of the most influential and surreptitious in securing industry’s foothold in US policy. For example, both President Obama and President Trump recruited former Raytheon lobbyists for senior posts at the Department of Defense (DOD) (William Lynn and Mark Esper, respectively). Obama’s Secretary of Defense Ashton Carter bounced between private defense consulting and jobs in the DOD, at one point serving in a position to advise the State Department on missile defense while receiving compensation from Raytheon for technical advising services. In keeping with tradition, President Biden chose General Lloyd Austin, a former Raytheon board member, as his Secretary of Defense. Upon leaving the Raytheon position, Austin stood to earn as much as $1.7 million in compensation from the role.

In 2016, there were 645 instances of the top 20 defense contractors hiring former senior government officials and other influential personnel. In the end, our system allows the same people who make decisions on behalf of the government to, not only be incentivized by the private sector to make certain decisions, but also see the promise of high-paying private sector jobs at the end of their government service. “Congressmembers are thinking ahead to retiring into a lucrative job in the industry and it affects how they regulate the companies while they’re still in government,” explained Hartung.

From the other side of the revolving door, there’s no overstating the effects on the government’s policy positions caused by its high recruitment of defense industry executives to top positions. “If you’re drawing from one sector alone, you get this group-think possibility, which could be dangerous,” Ranking Member of the Senate Armed Services Committee Jack Reed told reporters.

The many levers of influence arms companies appear to wield over the US government belies their own narrative as just the obliging contractors to the government. In fact, with this level of influence, it’s hard to parse government decision-making from internal corporate strategy.

The Ruling

Ultimately, with few regulations on the arms industry by the US government and little to no will in the industry for internal regulation of compliance with human rights standards, legal pressure may be a key instrument for change. “I’m not seeing this as an industry that is particularly concerned by reputational issues or concerned by ethical issues,” notes Wilcken. “I really think that legal obligation is probably the only thing that this type of industry [will respond to].” Wilcken added that “if there was a realistic prospect of successful litigation against a company, then I think they would invest resources in [human rights due diligence].”

“I’m not seeing this as an industry that is particularly concerned by reputational issues or concerned by ethical issues,” notes Wilcken. “I really think that legal obligation is probably the only thing that this type of industry [will respond to].”

The path forward for Ali v. Al-Nahyan is extremely narrow, given the restrictions on the ATS. But, a successful challenge to the arms industry’s impunity could help protect others from the atrocities suffered by the victims in this case. “[Liability is] the only language that these corporations understand. If it’s going to cost them money, then they’ll assume greater agency in doing due diligence to make sure their weapons are being used for a lawful purpose.” But Collingsworth warns: “If we lose, it’s going to drive them in the other direction. They’re going to stick their heads in the sand and say ‘we don’t even have to care what happens, we’ll just sell the weapons the government tells us to sell and that’s…not our problem’.”