The prior convictions that may lead to detention are broad: “Violations can range from serious felonies all the way down to a purely immigration violation (such as illegal entry which is a petty offense under the U.S. Code), or a violation which results in only in a fine such as not keeping a dog on a leash, fishing without a permit, driving a vehicle with a tail light out, etc.” A study investigating detainees on a single day in 2012 found that fewer than 10% were previously convicted of violent crimes.

“In detention [there are] a ton of very, very minor offenses,” Phil Torrey states. He spoke of a client of his who has been detained in immigration custody for over four years solely for two minor marijuana-related offenses. Notably, this client received no criminal detention because those offenses are decriminalized in Massachusetts.

Regarding risk of flight, data from 2008 to 2018 shows that 83% of non-detained people attended all of their hearings.

Multiple studies show that non-detained immigrants who have representation almost always appear in court; data from 2008 to 2018 shows that 96% of those who obtained a lawyer attended all immigration court hearings. A 2017 to 2019 Vera Institute study across 18 jurisdictions showed that 98 percent of non-detained people with representation continued to appear for their scheduled hearings. A separate 2014 to 2017 Vera Institute study in New York City showed that 98.4% of non-detained people with representation continued to appear for their hearings.

Multiple studies show that non-detained immigrants who have representation almost always appear in court; data from 2008 to 2018 shows that 96% of those who obtained a lawyer attended all immigration court hearings.

Notably, in absentia removal orders that indicate someone did not attend their court hearing may be an unreliable metric. These orders are often presented despite the person not being given adequate notice of the hearing, and from 2008 through 2018 15% of cases ordered removed in absentia have been reopened, illustrating that many of these orders are the result of something other than a desire to avoid court.

In absentia records may also be inflated, as immigration court records have labeled people as receiving these orders when their presence was never required in court. Some immigration scholars also criticize the government’s reporting methodology and argue that it inflates the overall in absentia rate.

This data indicates that, on average, non-detained people as a whole show up to court at high rates, and almost always attend court when they have legal representation.

In bond determination hearings, immigration courts implicitly recognize the presence of counsel as a factor weighing for release: judges are allowed to consider the likelihood that relief from removal will be granted as a factor for release, as it increases one’s motivation to appear for a hearing. Because people in immigration proceedings with attorneys are better able to present their cases, they are more likely to have relief granted, and therefore having representation is a factor intertwined with release determinations.

Data supports these claims: among detained immigrants, those with representation were twice as likely as unrepresented immigrants to obtain immigration relief if they sought it, and represented immigrants in detention who had a custody hearing were four times more likely to be released from detention.

Why Does Migrant Detention Prevail?

The majority of people in ICE detention have no criminal record, and the remainder have already been released by the criminal justice system. A large majority of people in immigration proceedings show up to court hearings even when non-detained, especially when they have counsel. So why does ICE continue to detain people at high rates?

Adelanto ICE Processing Center. Source: Peg Hunter/Flickr under a creative commons license

The detention industry has become profitable for private corporations, which have pushed for increased detention since the 1980s. Corrections Corporation of America, now CoreCivic, opened the first private detention facility in 1984, with the company’s co-founder Don Hutto fingerprinting the detainees personally. Today, the private prison industry has a significant influence on the amount of detention that occurs and on the subsequent contracts and revenue that the private prison industry receives.

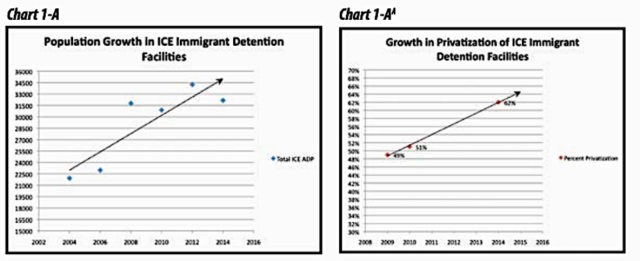

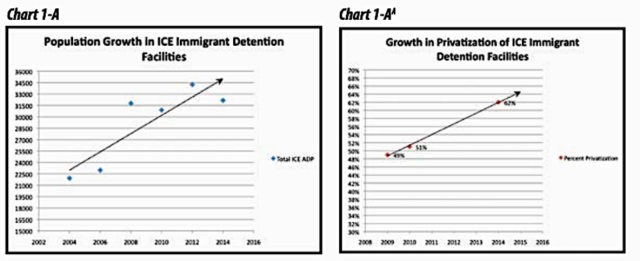

The power of the private industry is illustrated by the rise of detention numbers coinciding with the takeover timeline of private detention centers.

In 2005, 25% of immigration detention occurred in for-profit detention centers, and this increased to 62% in 2014. In January of 2020, 81% of ICE detention occurred in private prison facilities, and in July 2023 the number was 90.8%.

Concurrently, the number of required available detention beds has increased. The Department of Homeland Security Appropriations Act of 2010 introduced a bed mandate of 33,400 beds, which increased to 34,000 in 2012. In fiscal year (FY) 2023, 34,000 beds were funded.

Coinciding with the implementation of the bed mandate and the takeover of private detention facilities was the growing number of people in ICE detention. In 2004, the average daily population of people in ICE detention was 21,928, and by 2014 it was 32,163. The number of detainees on a particular day reached a high of 55,654 during the Trump administration and a low of 13,258 during Covid, but it has returned back to the thirty thousands; on April 7, 2024, there were 34,580 total people in ICE custody.

Notably, the dip in detention numbers during the beginning of the pandemic in part reflect ICE temporarily altering its enforcement policy to focus on “public safety risks and individuals subject to mandatory detention based on criminal grounds,” demonstrating how ICE has the power to discretionarily reduce enforcement against people who ICE itself sees as less of a risk.

Average daily population and privatization grew simultaneously from 2004 to 2014, from Grassroots Leadership Detention Quota Report

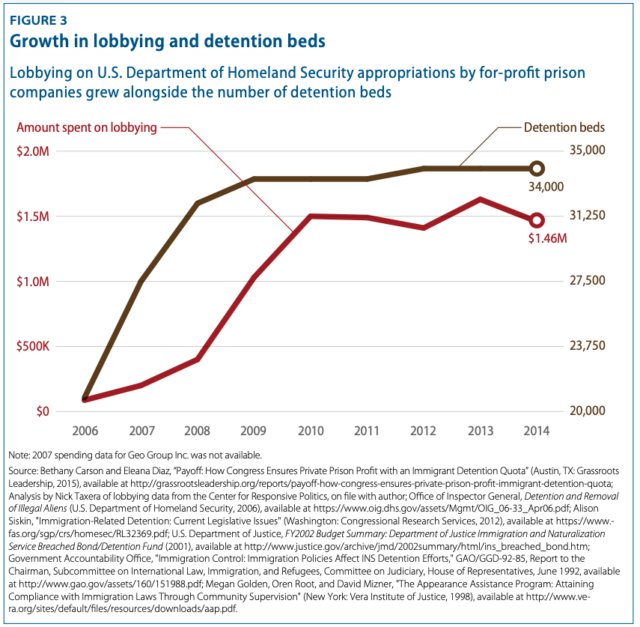

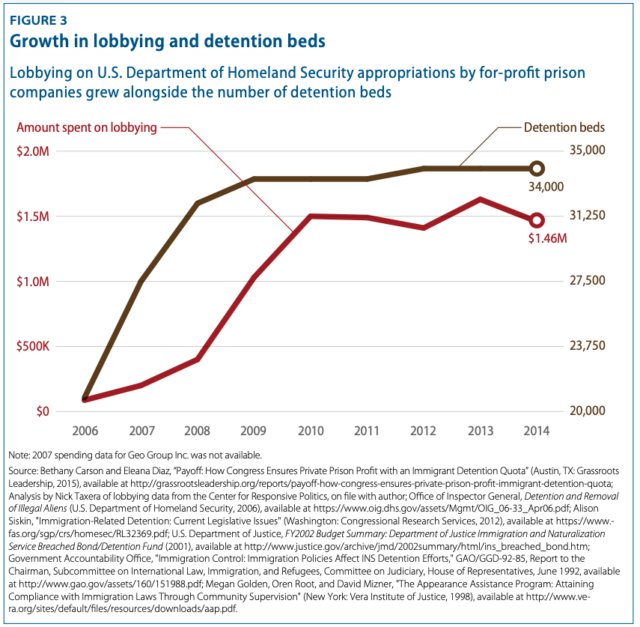

The lobbying efforts of private prison corporations provide an explanation for how they were able to take such strong control of the immigration detention space and essentially create a for-profit industry. From 2004 to 2014, CoreCivic and GEO Group spent $18 million and $4 million on lobbying, respectively. Between 2006 and 2015, CoreCivic spent more than $8.7 million and Geo Group spent $1.3 million to lobby Congress solely on DHS appropriations, which is in control of the bed mandate.

Mirrored trends of lobbying and detention beds from 2006 to 2014, sourced from Sharita Gruberg and Center for American Progress

As a result of the increased detention, government spending on immigration detention increased from $700 million in FY 2005 to nearly $2 billion in FY 2014.

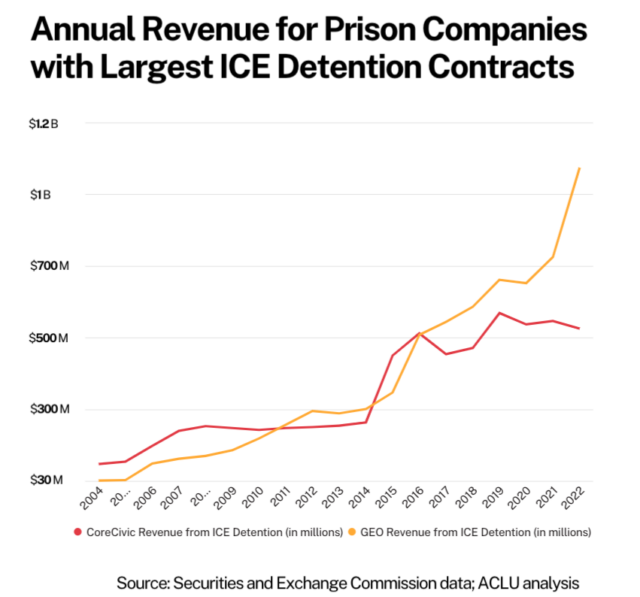

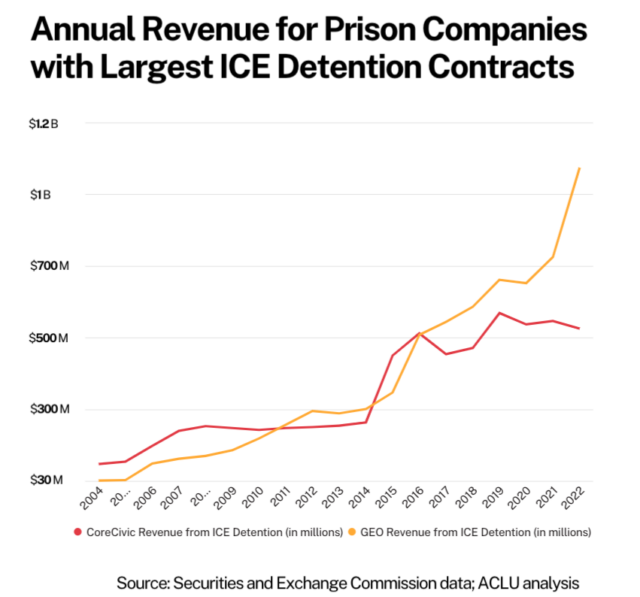

This expansion is reflected in the increasing size of contracts made between ICE and these companies during that period. CoreCivic earned ICE contracts worth $95 million in FY 2005, $196.6 million in FY 2010, and $221 million in FY 2014. GEO Group earned ICE contracts worth $33.6 million in FY 2005, $216 million in FY 2010, and $263.6 million in FY 2014.

Government spending and ICE contracts have continued to grow in recent years. In FY 2023, congress appropriated $2.8 billion on custody operations for 34,000 beds. In 2022, GEO Group had $1.05 billion worth of contracts with ICE ($408 million for electronic monitoring), and CoreCivic had $552.2 million worth of contracts with ICE.

Graph sourced from ACLU

Detention Obstructs Access to Counsel

People facing removal while in detention are far less likely to have legal representation. A 2007 to 2012 study found that 86% of detained immigrants were without counsel, while 34% of non-detained immigrants were without counsel. People in detention must rely on the facility phones to contact attorneys and cannot work to afford private counsel.

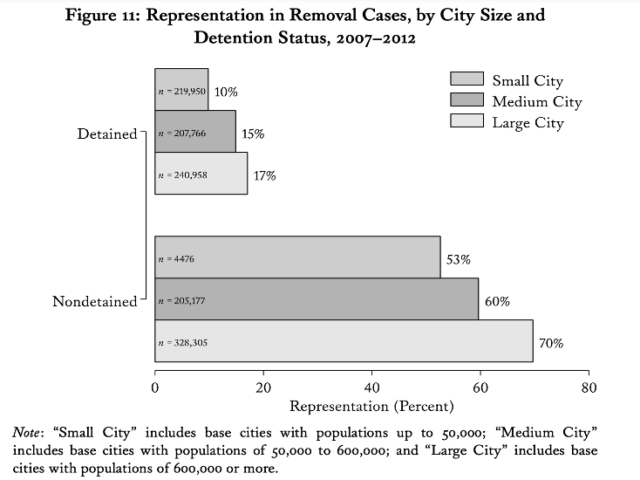

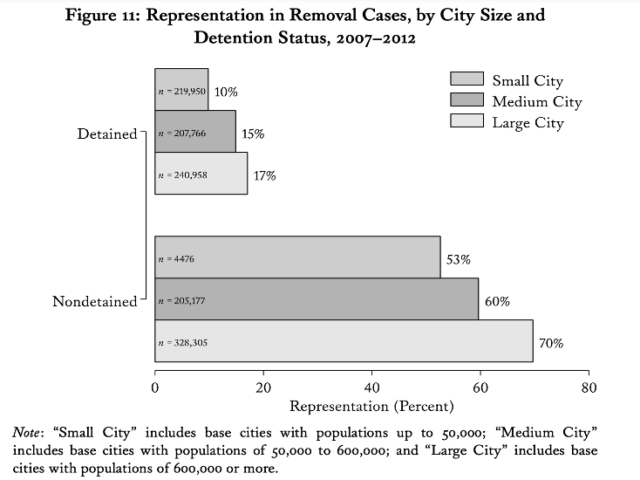

Another explanation for this disparity has to do with the location of private detention facilities, which are often very isolated in more rural areas. “Private prisons obviously are trying to maximize their profit margins, so if they’re in more rural areas where leases are cheaper, they can have sort of a larger footprint and it keeps their costs down. And in those rural areas, there’s access to counsel issues,” stated Phil Torrey.

In rural areas and small cities, the number of immigration lawyers is almost nonexistent.

Data shows that both detained and non-detained people were less likely to acquire counsel when their cases were decided in a small city. That being said, this was almost exclusively an issue for detained people; from 2007-2012, only 4,476 non-detained cases were adjudicated in small cities while 219,950 detained cases were adjudicated in small cities. This data demonstrates that detention, which is largely private, commonly takes place in isolated areas and reduces access to counsel.

Source: University of Pennsylvania Law Review article by Eagly and Shafir

Public Detention and Alternatives to Detention

Private detention is the focus of this report because public detention makes up less than 10% of ICE detention. Additionally, the companies such as GEO Group and CoreCivic have created an industry out of detaining people that creates a feedback loop of profit, which in turn leads to lobbying, which leads to a greater manufactured need for detaining immigrants, which leads to profit once again.

That being said, the conditions in public, government-run detention facilities are not markedly better. One participant in the Harvard solitary confinement study who was detained at Bristol County Correctional Facility stated that he was placed in solitary confinement after he had been assaulted by a correctional officer and told officers that he had chest pain from the assault. Another participant detained in Orange County Jail (New York) said he was put in solitary confinement for going on a walk without a uniform and for using the stove to heat up coffee. When a person detained at Orange County Jail asked for water, he stated he was told to drink from the toilet. The shift to public detention therefore, while preferable to private detention as it would largely eliminate the profit motives, is not going to eliminate the issues of abuse.

ICE also uses “alternatives to detention” (“ATD”). As of April 6, 2024, 183,901 people were subject to ATD by ICE, the vast majority being tracked by SmartLINK, a smart phone application that uses facial recognition and GPS location monitoring. Other forms of ATD include ankle and wrist monitors, and telephonic reporting. ICE has touted the cost effectiveness of ATDs as costing less than $8 per day per participant, compared to $150 per day for detention, and ATDs can cost as little as 70 cents per day.

ATDs are preferable to detention, but they are not free of issues: one 22-year-old asylum seeker became at risk of losing his foot after his ankle monitor caused a skin infection. A survey of people subject to ICE ankle monitoring found that 90% of survey participants experienced physical pain, numbness, swelling, or electric shocks. 88% reported negative impacts to their mental health, with 12% reporting suicidal thoughts. Nearly all survey participants experienced social isolation due to the stigma of the ankle monitor. 67% reported financial hardship to themselves and their families due in part to difficulty being hired. And Black people were disproportionally subjected to ankle monitors by ICE.

ATDs are also another avenue for corporations to profit off of migrants, evident in the $408 million contract for electronic monitoring earned by GEO Group from ICE in 2022. Further, the vast number of people on ATDs alone calls into question the genuineness of whether ATDs are truly alternatives to detention, as opposed to alternatives to release.

![[F]law School Episode 10: Mass Incarceration, Inc.](https://theflaw.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/RICHARDS_PHOTO_Protest2-640x427.png)