Review of the NCLB’s impact is mixed. Some point as evidence of its success the fact that reading and math scores by Black students improved during the time of the NCLB. Perhaps the greatest indicator of whether the NCLB succeeded is that it was replaced in 2015 by the Obama administration’s Every Student Succeeds Act. Nevertheless, regardless of whether one sees the NCLB as having met its goals of “raising the floor” for every American student, certainly its most visible impact on modern American education is its overemphasizing of standardized testing to measure student success.

The pivot to standardized testing as the primary tool for assessing students as a result of the NCLB resulted in the gamification the education system and directly led to the mid-2000s boom seen by the test prep industry.

The NCLB created the phenomenon among public school teachers of “teaching to the test” whereby instead of seeking to holistically develop students and nurture an interest in learning, educators were incentivized and pressured by supervisors to shape their lesson plans around frequently-tested material on state examinations.

Schools, fearing the program’s “stick” in the form of decreased funding because of not meeting test score minimums, shifted their attention to tested subjects such as math, reading, and writing at the expense of non-tested subjects such as civics and the arts.

This prioritization of certain subjects over others betrayed the NCLB’s purported goal of ensuring children obtain a “high-quality education” by hurting students’ holistic development. Moreover, a study has shown that even when students’ test scores have increased, this may not accurately represent “students’ mastery of the state standards.”

The pivot to standardized testing as the primary tool for assessing students as a result of the NCLB resulted in the gamification the education system and directly led to the mid-2000s boom seen by the test prep industry.

Shortly after the NCLB was signed, researchers had already made predictions that the test prep industry would grow due to the NCLB’s annual testing requirement. A survey of various research studies in 2021 found that, in just a few years, the test prep industry grew astronomically from a $50 million “modest” market in 2002 (the first year of the NCLB’s implementation) to a $22 billion industry just a few years into the NCLB era. The survey found that studies have shown a link between the industry’s exponential growth and “heightened demand for services that support students in mastering standardized tests like the SAT and ACT.” Many of the giants in the test prep industry today such as Kaplan and Princeton Review saw an over 200% increase in sales in just the first year of the NCLB’s implementation.

The newfound importance of standardized exams was an opportunity eagerly pounced on by test prep companies. Princeton Review benefited from being an early mover by securing contracts with school districts across the country to provide its services to their students in hopes of increasing the students’ test scores. Many schools signing these contracts faced decision about where the money to pay Princeton Review would come from. For some schools, it came at the cost of non-test subjects such as physical education and musical electives. One public high school located in Washington D.C. prioritized paying Princeton Review’s $21,000 fee instead of buying more computers from students.

The NCLB era was not just the rise of the standardized testing industry. At the same time that test prep companies were pushing their SAT and ACT services onto more and more public schools, these companies were also pushing their college admissions consulting services. During Princeton Review’s nationwide contracting spree, one of the agreements it made was with the Texas state government to provide middle and high schools with the company’s private college counseling advisers.

The test prep industry has significantly matured from parents hiring older neighborhood kids to now franchises of national chains located in nearly every school-adjacent area. A recent study at Brown University found that whereas in 1997 there were only 3,000 private tutoring centers in the United States, that number had more than tripled by 2022 to well over 9,000. The Brown study also found that of the 9,000+ private tutoring centers, just 10 chains accounted for 43% of those locations. One chain, Kumon, accounted “for nearly 20% of all tutoring centers in the United States that year.” This suggests that not only did the test prep industry balloon in size, but it also became concentrated in a few major players.

Targeting Asian American Communities

Today, private tutoring centers have become part and parcel of the everyday life of your average Asian American teenager. Michael, whose name has been changed for his privacy, grew up in a predominantly Asian American community and attended a high school that was majority Asian American. During middle and high school, he took private tutoring as well as SAT test prep at the behest of his parents. These SAT review centers were ubiquitous in his and his friends’ lives as almost everyone he knew was in the same or a similar program.

Michael described having heard about these test prep centers after receiving emails after signing up with CollegBoard, the non-profit organization that administers the SAT as well as other exams necessary for college admissions such as Advanced Placement Tests and SAT Subject Exams.

Today, private tutoring centers have become part and parcel of the everyday life of your average Asian American teenager.

Michael and his friends’ experiences are not unique. Asian American kids take SAT prep courses at higher rates than other students, with some groups (namely, East Asian Americans) taking commercial test prep courses at 3x the rate of White students. The test prep industry has capitalized on and facilitated this trend by targeting Asian American-heavy communities such as the San Gabriel Valley, where Michael is from.

Test prep centers can be seen on virtually every block in areas with large Asian American populations. For example, you will find multiple branches of national test prep chains like Prep Center and Princeton Review in or near Los Angeles’s Koreatown and other communities with large Korean populations “where they are advertised in Korean newspapers with promises of helping students excel in school, score high on standardized tests, assist in the college application process, and get into the college of choice.”

Overcharging and Underdelivering

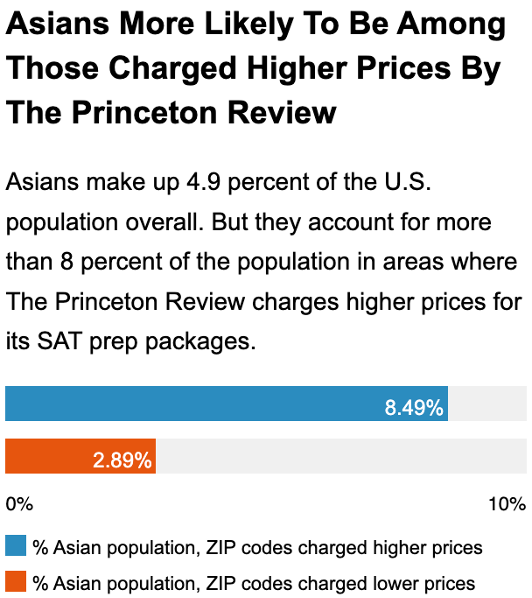

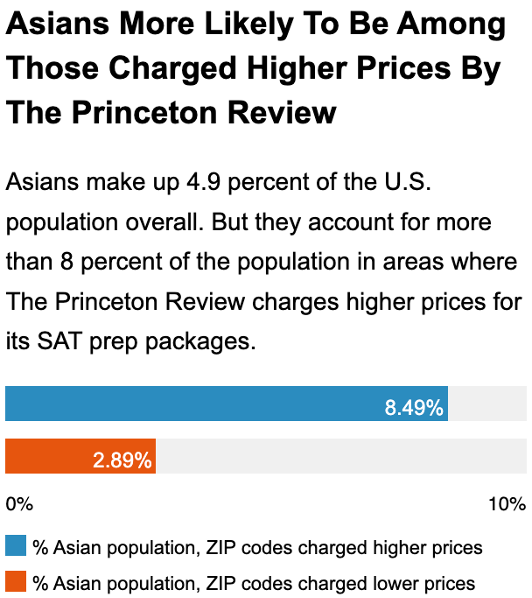

Test prep companies have not only taken advantage of Asian American communities by filling them with more branches but also charging them higher prices. It has been found that the branches of national chains such as Princeton Review charge the most expensive prices in areas with high Asian American populations.

The study that made this finding also found that the trend remains true even when controlling for income. For example, in the community of Flushing, Queens which is 70.5% Asian and where the median household income is below the national average, families were still charged the maximum price for Princeton Review’s courses.

ProPublica, 2015

This means that low- and middle-income Asian American families are unfortunate victims being more likely to enroll their children in test prep courses even despite having to pay a higher cost than other similarly situated families. One example is Michael’s family, whose parents chose to take on loans just to afford his SAT review courses.

With all the impetus on taking a review course, it is important to ask: are they even really that helpful? Test prep can often be a double-edged sword. The companies providing these services claim to increase test scores by hundreds of points, but average gains are more often in the range of 10-30 points.

Additionally, the extra time spent studying outside of school, combined with the pressure imposed by the perceived importance of excelling on the SAT, leads to increased stress disproportionately on Asian American youth. Students like Michael have to juggle their review center time along with other activities they pursue to strengthen their college applications—extracurriculars such as sports, academic competitions, and performing arts.

Fueling the Pernicious “Model Minority” Myth

While some attempt to paint Asian American educational success as a triumphant story of meritocracy at work, this narrative obfuscates the serious harms done to students and fueled by the test prep industry in the process. In a world where the highest paying jobs and most sought-after opportunities are concentrated among graduates of elite universities, the competition to get admitted to these schools has created a severe mental health epidemic among Asian American teenagers.

Unfortunately, the test prep industry’s targeting of Asian American communities does not just cause financial harm. It has also fed into the pernicious “model minority” myth—that Asian American immigrants have achieved relative socioeconomic success compared to immigrants from other regions due to a cultural emphasis on education, a strong work ethic, and exhibiting greater obedience to authority. This myth is based on stereotyping that, although on the surface may appear positive, essentially reduces Asian Americans to a demeaning caricature of a submissive and robotic worker-bee.

The myth specifically harms low-income Asian Americans, particularly those who migrated as refugees from southeast Asia, by making them less visible to government initiatives aimed at supporting low-income minorities, as it falsely groups all Asian Americans into a middle- to high-income monolith.

It is even worse for those who, despite all the extra hours spent studying, are still unable to achieve the scores and grades they seek since the model minority stereotype can be “dehumanizing” by punishing those who deviate from its very narrow conception of “success.”

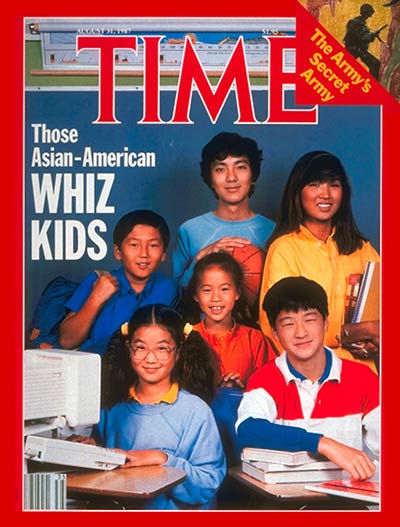

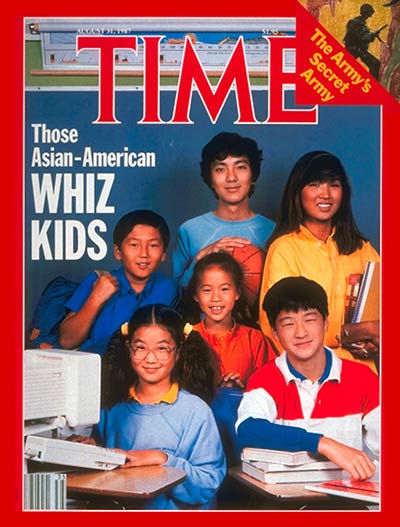

The myth begins at an early age with the cliché of the Asian American “whiz kid”—picture a bowl haircut, thick-framed glasses, and an SAT prep book in hand. The test prep industry not only profits off this stereotype, but feeds into it as well.

Since the passage of the Immigration and Nationality Act in 1965 which eliminated quota systems and preferential treatment of immigrants from Northern and Western Europe, immigration from Asian countries has skyrocketed. The population of Asian Americans in the United States was 980,000 in 1960—the first census that allowed individuals to self-report their race. In 2023, the Asian American population was 19.36 million.

The myth specifically harms low-income Asian Americans, particularly those who migrated as refugees from southeast Asia, by making them less visible to government initiatives aimed at supporting low-income minorities, as it falsely groups all Asian Americans into a middle- to high-income monolith.

Historically, rapid growth in immigration from a single region has been accompanied by nativist hostility rooted in cultural anxiety. Indeed, anti-Chinese animosity in the late 19th century due to the influx of Chinese immigrants during the Gold Rush led to the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1892. However, the modern iteration of increased immigration from Asia has instead been viewed in American culture through a lens of “positive stereotyping.” Modern Asian American immigrants have been able to avoid the more unsavory stereotypes of immigrants—namely, groups who bring crime and drain public resources. Instead, American culture has painted a rosier picture of Asian American immigrants as being “unusually well educated, prosperous, married, satisfied with their lot and willing to believe in the American dream[.]”

Time Magazine: Aug. 31, 1987 Cover.

Asian American immigrants are a large and multifaceted group comprised of several subgroups, some of which are among the poorest ethnic groups in the United States. American culture has chosen to highlight certain Asian subgroups, namely highly educated individuals coming to America on H1B visas for skilled workers, as evidence that immigrants can also achieve socioeconomic success in America if they just “worked hard enough.” And so, despite the harsh inequalities present within the Asian American community, they have been presented on the whole as a “model minority” for other immigrant groups to seek to emulate.

Nowhere is the model minority stereotype more visible than in education. Despite Asian Americans making up only 7% of the American population, they are significantly overrepresented in America’s elite universities. Even Harvard, which has faced several allegations in recent years of discriminating against Asian American applicants, has an undergraduate population comprised of 37% Asian American. Logically related to Asian Americans’ overrepresentation in elite colleges is their overperformance in metrics used for college admissions. One of the most striking examples is the math section of the SAT where Asian Americans constitute 60% of 750-800 scorers (the top percentile).

Even though the model minority myth is couched in language of objective meritocracy, in actuality it has been used to drive wedges between minority groups based on prejudicial cultural stereotyping. A bad ethos interpretation would be that Asian Americans deserve their success because of a perceived cultural superiority advantaging Asian American students in competitive academic environments. Conservatives have weaponized these prejudices in their fight against programs intended to remedy historical injustices by using Asian American students as plaintiffs in anti-affirmative action litigation.

In Students For Fair Admissions v. Harvard, a case brought by the conservative legal movement using Asian American plaintiffs claiming anti-Asian discrimination in admissions by Harvard College, the Supreme Court barred the use of race as a factor in college admissions. Following the SFFA decision, enrollment of Black and Hispanic students at top universities declined, but enrollment of Asian students did not see an equivalent increase.

A parent protest in support of Students For Fair Admissions’ lawsuit against Harvard. Photo by user Whoisjohngalt on Wikimedia Commons.

When the case was initially decided, some in the conservative media described it as a supposed victory for the Asian American community. This is despite the fact that a coalition of the largest Asian American civil rights and advocacy groups filed an amicus (friend of the court) brief in support of Harvard’s race-conscious admissions program.

A key element of anti-affirmative action arguments is the notion that elite universities discriminate against Asian American applicants based on a finding that they require Asian applicants to have higher test scores to be admitted compared to White, Black, and Hispanic applicants. Thus, even if the model minority myth paints a positive stereotype of Asian American kids as academic achievers, it actually penalizes Asian American students by driving the narrative that they are just expected to perform better than other students, on average, and therefore need to have even stronger scores and applications than non-Asian applicants.

Pressure Cooker Race to the Bottom

And so, we now have a group of kids who have been told by society through television, media, and perhaps even by their own parents or their friends that they are expected to not just pass, but excel in their academics. These kids are also conscious of the sacrifices made by their parents or older relatives to immigrate to America which only adds further pressure to succeed out of an obligation to make those sacrifices worth it. And because of media narratives, the only vision of success these kids see as available to them is through education.

Then you give these kids an exam and tell them that it will essentially dictate whether or not they achieve that success: from what college they attend to what careers they will be able to attain. Great—these kids have always been adept at test-taking so this should be a straightforward experience, right?

But then the kids are also exposed to other media narratives that their previous academic success is actually to their detriment: now they have to work even harder to get a higher score to reach their goals. Lastly, also add in the fact that these kids have grown up in an education system wherein schools have instilled the importance of a standardized test at the end of each year.

This is the fertile ground within which the college admissions industry operates and profits to a significant degree. The industry successfully exploits the toxic combination of parents anxious for their children to survive in a foreign land and children who constantly feel that they could always be doing more.