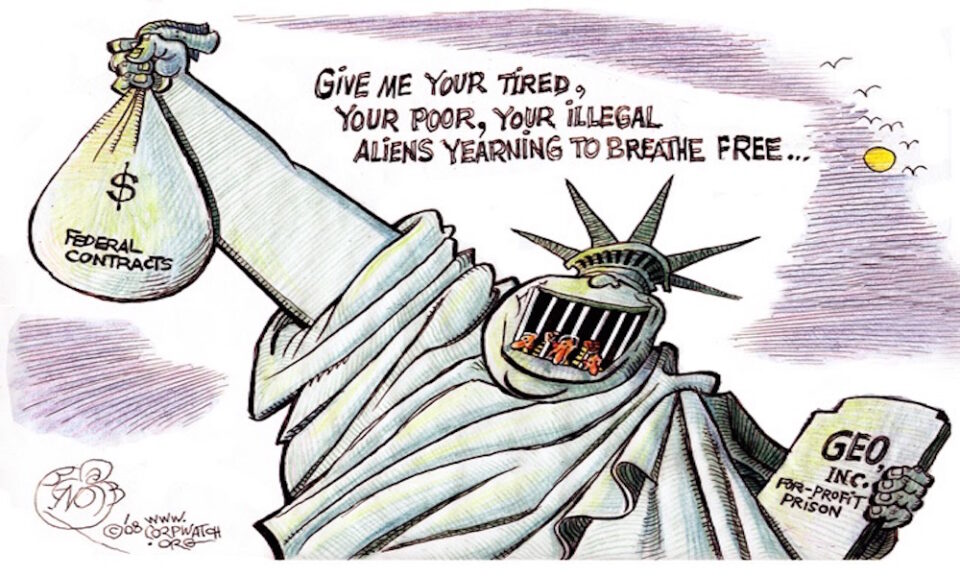

By and large, private prison industry has been very active in supporting and pursuing immigration policies that increase the use of detention as a mode of immigration enforcement. That has really been the case, even before the bed mandate.

~ Phil Torrey

Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act

As Friedman, and later President Bush believed, markets serve as solutions to the problems of regulation. In a 2002 tribute to Friedman, President Bush praised Friedman for having “creatively applied the power of freedom to the problems of our own country […], shaping policies ranging from ‘national security’ to ‘educational reform.’” The idea of using markets to solve issues of national security is prominent in the solutions put forth in the context of immigration, particularly after the tragic events of September 11, 2001. Though, the market solution to immigration detention capacity—the privatization of detention facilities—has its roots in the 1990s and the expansion of mandatory detention through the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996 (IIRIRA).

IIRIRA expanded the definition of what is known as an “aggravated felony,” exponentially increasing the use of mandatory detention to detain criminal immigrants and limiting opportunities for judicial review and/or bond. Though the term “aggravated felony” sounds ominous, IIRIRA defines such crimes rather broadly, including many nonviolent and minor offenses like simple battery, theft, filing a false tax return, and failing to appear in court. An immigrant convicted of such a crime becomes immediately deportable, even if they are lawfully present within the United States, and is subject to mandatory immigration detention following release from criminal custody. Further, the “aggravated felony” mark on their record bars them from seeking various forms of immigration relief, including cancellation of removal, waivers of inadmissibility, and asylum.

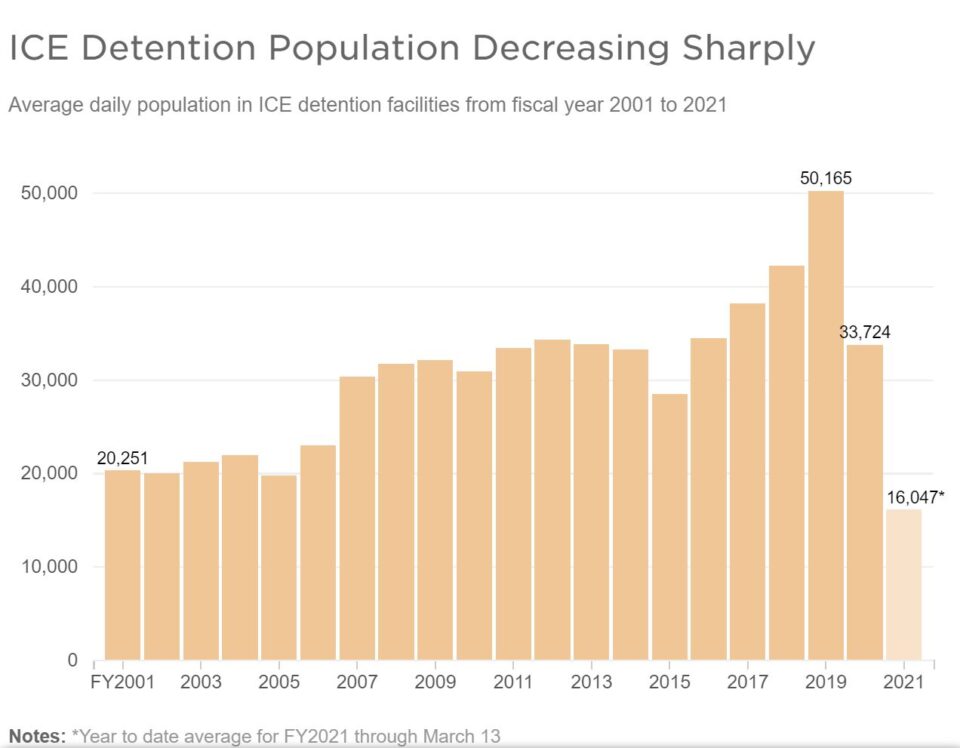

Following the implementation of IIRIRA, rates of immigration detention steadily increased through the early twenty-first century. While immigration detention centers had the capacity to detain just over 4,000 in 1980, the number of beds reached 6,785 by 1994, and 33,400 by 2009 (particularly at the implementation of the bed mandate, discussed below). Humiliating conditions within detention facilities continued, as detailed in Jama et al v. U.S.I.N.S. (1998), a lawsuit brought forth by detainees against Correctional Services Corporation (formerly Esmor Correctional Services Inc.). In Jama, detainees alleged in their amended complaint that conditions within their privately run detention facility (located in Elizabeth, New Jersey) were “subhuman”:

Every moment of [detainees’] detention was filled with abuse. They could not escape from these abuses even in their dreams, as they were not permitted to sleep [as] bright lights shone on them 24 hours a day, and guards woke them up just to taunt them.

Within this facility, twenty to forty detainees were placed into each room. There was no privacy, and sexual abuse and humiliation were rampant in cells, as graphically detailed below:

When women detainees showered [in their shared room], guards made crude sexual comments about their bodies. […] The guards woke [detainees] before sunrise and forced them to stand facing a wall, with their legs spread, for up to an hour at a time. Upon searching male [detainees’] genital areas, the guards forcefully yanked their genitals causing severe pain. There was inappropriate touching of both male and female [detainees]. […] Moreover, female detainees were forced to choose between being sexually assaulted and contacting their lawyers as guards premised using the telephones on submitting to their unwanted sexual advances.

Detainees within this facility were also subject to racism and denied access to legal representation, often losing their chance to seek asylum as a result.

In addition to beating them, they yelled racial and ethnic epithets at them such as “African Monkeys” from the “jungle.”

[G]uards, without any justification, often would refuse to allow plaintiffs to use the telephone to discuss their asylum cases with their counsel. Additionally, defendants continuously failed to transport plaintiffs promptly to their asylum hearings. As a result, plaintiffs often missed important asylum meetings (which resulted in a postponement of their asylum hearings) and prolonged their detention at Esmor.

IIRIRA was only the first sign of incoming restrictive litigation expanding immigration detention. Following the events of 9/11, the Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act of 2004 passed soon after.

Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act

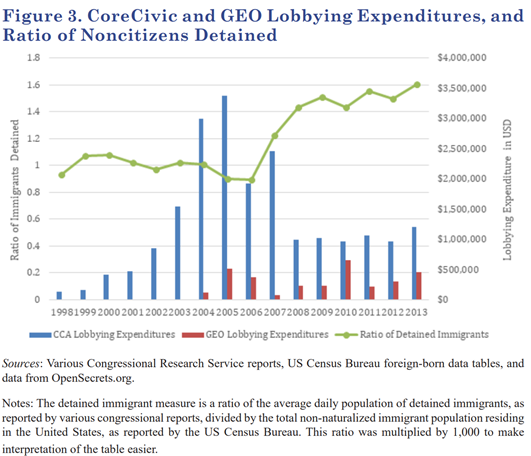

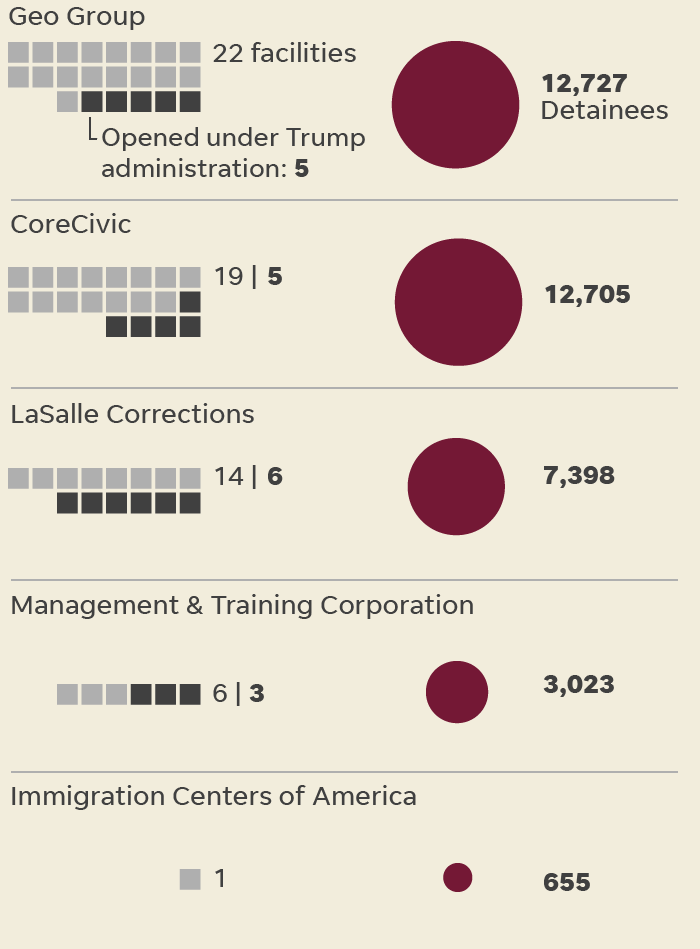

The Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act of 2004 (IRTPA) directed DHS to increase “the number of beds available for immigration detention” and required the “expansion of immigration detention bed capacity be contingent on the ‘availability of appropriated funds.’” Looking at the figure above, it is hard to ignore the spike in CoreCivic (formerly CCA) and GEO Group’s lobbying expenditures during the time of IRTPA’s passage. Furthermore, CoreCivic’s annual report (2004) praised the passage of IRTPA as follows:

The Intelligence Reform Bill authorizes the Department of Homeland Security to, subject to appropriations, hire a total of 2,000 new border patrol agents over each of the next five years and increase the total available detention beds by 40,000 over the next five years. We believe these initiatives could lead to meaningful growth to the private corrections industry in general, and to our company in particular. We believe these initiatives could lead to meaningful growth to the private corrections industry in general, and to our company in particular.

Upon the enactment of IRTPA, President George W. Bush ended the controversial “catch and release” policy which expedited deportations without formal hearings and removed the need for detention. Though the policy received criticism for its mass prosecutions without due process protections, it eliminated the need for immigration detention. After its enforcement stopped in 2006, the subsequent regime of immigration detention quickly took its place as the Bush administration ramped up its contracts with private prison corporations and expanded immigration detention to record-setting levels. Through federal contracts, CoreCivic and GEO Group built new detention facilities around the country. For example, CoreCivic’s T. Don Hutto Family Detention Center (Hutto) near Austin, Texas opened its doors to immigrant detainees, mostly families, in 2006 under a $2.8 million-per-month federal contract.

We believe these initiatives could lead to meaningful growth to the private corrections industry in general, and to our company in particular.

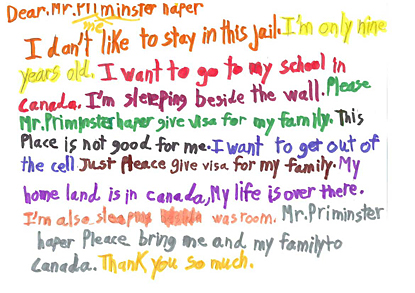

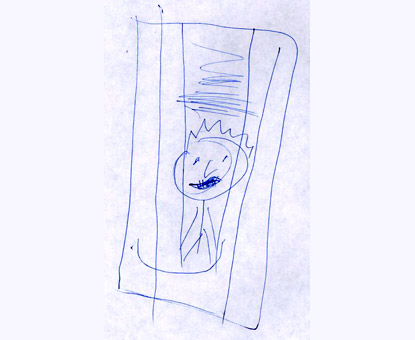

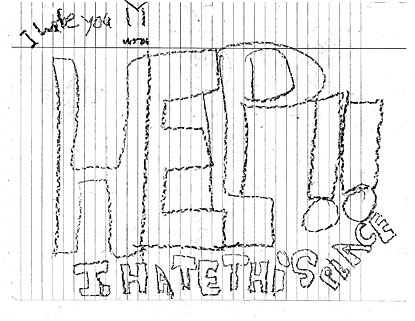

Soon after, however, evidence of poor conditions within Hutto came to light in a settlement reached between the ACLU and DHS. The ACLU initially filed on behalf of twenty six immigrant children, between the ages of 1 and 17, who were detained in Hutto with their parents awaiting asylum proceedings. In Hutto, children were often separated from their parents during prison-like headcounts, forced to wear prison garb, and received only an hour of educational instruction a day. Through the landmark settlement, DHS officials must expand educational programming, ensure access to full-time pediatricians, and eliminate the headcount system, among other requirements. Though, the damage to children detained in Hutto is long lasting, as evident in a statement made by Andrea Restrepo (then 12 years old at the time of her release post-settlement):

I feel much better, I feel tranquil, I can do things now I couldn’t do there […] I am trying to forget everything about Hutto. I feel free. It was a nightmare.

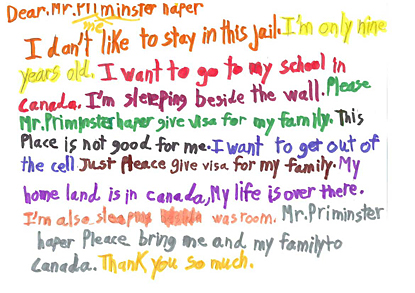

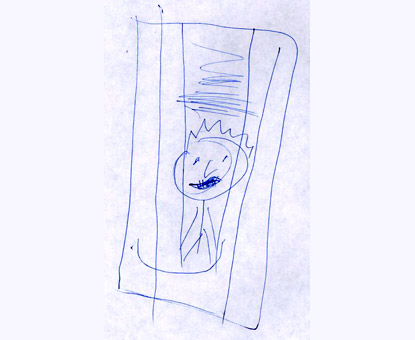

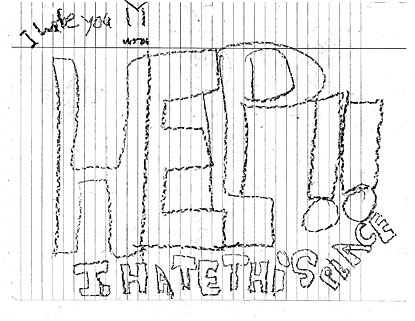

Andrea spent almost a year in a small Hutto cell with her mother and younger sister. Other stories like Andrea’s came out of Hutto, as illustrated in children’s drawings from detention below.