The progressive weakening of worker protections and bargaining power through policy, administrative, and court decisions has culminated in greater obstacles in each part of the unionization process. To successfully unionize and bargain for a contract, workers must: 1) obtain signed union cards from 30 percent of employees to ask the government to hold an election; 2) win a majority in the election; and 3) secure a first contract with their employer.

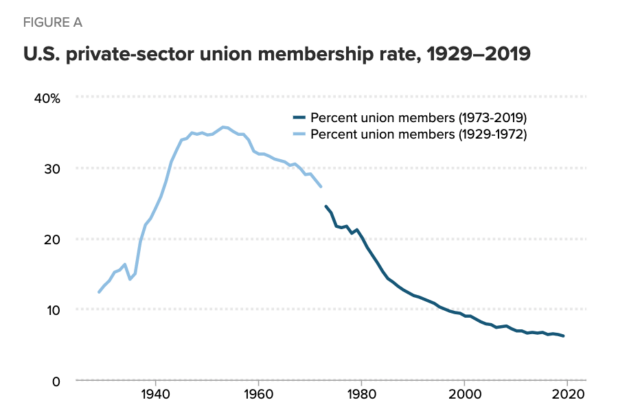

Fewer employees are voting in elections, with election participation down 90 percent since 1950. In the same period, workers have gone from winning two-thirds of their elections to just above half. With a weakly enforced requirement to bargain in good faith, the rate of winning a first contract dropped by 30 percent from the 1950s to the 1990s. While successful union elections expanded the share of unionized private sector workers by 8.7 percent in the 1950s, in the 2010s, the share of unionized private sector workers has grown by only 0.5 percent.

“One part of the story for sure is intense opposition from corporate management, coupled with a very weak set of legal protections for union activity—you put those two things together and you’ve got a recipe for not having unions,” Professor Sachs told me. “Look at how incredibly difficult it is to form a union. It shouldn’t be hard to form a union. It should just be a simple process of, ‘Do 51% of the workers want a union? Let’s have a vote.’ And get on with it. But you have these protracted battles where workers are fired, where you know they’re bombarded with anti-union propaganda, and the law does very little about it.”

The sad state of union density stands in stark contrast to the desire and approval of unions in the broader public. 68 percent of Americans approve of labor unions, the highest rate since 1971. 48 percent of Americans would “join a union in their workplace tomorrow if they got the chance,” revealing a huge gap between those who want union representation and the 10 percent of Americans who actually have it.

Politicians have taken note of public opinion, with the House of Representatives recently passing the Protecting the Right to Organize Act (PRO Act), a labor law reform bill supported by the Biden Administration that would allow unions to override restrictive right-to-work laws, reduce employer interference by making mandatory anti-union company meetings illegal, and create real penalties for companies and executives that violate workers’ rights. The legislation has little hope of passing the evenly divided Senate, where Republicans can easily use the filibuster to kill its prospects. But even if the law remains unchanged, that will not stop workers from making change themselves.

For many workers, the pandemic crystalized the need for union representation in their workplaces. Bailey Fulton and Jacob Roessler, baristas from a Starbucks in the neighboring city of Worcester who attended the Boston vote count in solidarity, told me about how their experiences as workers throughout the pandemic influenced their perspectives about their own jobs.

Though Starbucks closed her store and others for several weeks when the pandemic began, Bailey told me she was shocked to discover that drive-through locations never closed. “Those partners were never given the opportunity to stay home.” Bailey also worked at Whole Foods during the pandemic. “All of a sudden, we were like, the heroes…people were just like, ‘I’m so glad you’re here!’ And I was like ‘Really? I’m not! I don’t know if I’m gonna die from something you breathe on me right now, and I’m not getting anything to support me in that.’”

The country’s reliance on laborers throughout the pandemic juxtaposed with corporate flippancy towards worker safety revealed the tilted scales of the employer-employee bargaining relationship. “The worker was put on a pedestal—the retail associate, the service employee, the so-called ‘essential worker,’” Jacob told me. “It was the incredibly quick drop-off of that status as soon as the pandemic had lessened and things were opening up—I think that shook a lot of people. It kind of made me realize, ‘you send me out to die before you give me a living wage.’”

The country’s reliance on laborers throughout the pandemic juxtaposed with corporate flippancy towards worker safety revealed the tilted scales of the employer-employee bargaining relationship.

Things will not be returning to the pre-pandemic status quo. Workers who endured the pandemic are fed up and demanding more power to decide the terms of their employment. But corporations seem to have a stranglehold on our laws, courts, and the tools of democracy that will prevent any significant structural change. So how can labor pull itself from the ashes in the face of a static system? Can individual workers mount a serious challenge within a system that it is stacked against them? Will the pandemic’s long tail and the rising tide of unionization lead enough dissatisfied workers to consider organization over resignation?

Professor Sachs says these are “million-dollar questions,” but he is optimistic. “This is probably a hopeful answer, but I think there’s a conjunction of workers having lived through the pandemic, having been told that they were essential, having been exposed to terrible conditions, fueling a kind of militancy. You couple that with a tight labor market, and you get a willingness to demand change for the better. Then you locate that in a political context where you have a pro-union president and a general counsel of the Labor Board, willing to really, really go out on a limb to protect workers’ rights, and I think there is reason to be optimistic that this will be more than a blip. And we know from the history of organizing that success breeds success. The Buffalo example is a terrific one. When workers see that they can win, they’re more likely to try.”

Boston may be yet another example. Bailey and Jacob, along with the other Worcester partners, had just filed their own union paperwork a few weeks before the Boston stores’ vote count. “We’d seen Buffalo a month or two prior, then Boston, and we were like, ‘well, that’s like an hour away,” Jacob told me. “The struggle is incredibly similar at every store, so when you know you’re experiencing the same working conditions, you feel like your concerns are real and validated as well.”

Moreover, seeing the types of union-busting tactics Starbucks employed in Boston, Jacob said the Worcester partners know “what to look out for” and are “ready to respond.” Just as the Coolidge Corner store had worked with an organizer from Buffalo, Bailey told me workers at the Worcester store were setting up a meeting with Kylah, the barista and law student from Commonwealth Ave, and an attorney to learn about some of the legal aspects of the process.

Corporations have sought to weaken organized labor because they fear the power of the people united. Collective organizing has transformative potential, the fruits of which I experienced at that small bookstore basement in Boston. “I was actually gonna move to LA in June, but I decided to stay in Boston because I wanted to bargain,” Maria told me. “This is a way I can contribute to a movement that will help fix the issues that I feel strongly about.” Weeks after we spoke, I happened to walk past Maria speaking to a crowd at a May Day rally in Cambridge, sharing her story to encourage organizing efforts across the city.

Tyler, who is graduating from law school in May, decided to divert his plans as well. “I’ll tell you this: I’m not taking the bar in July. I was going to go back to California, but I’m staying up here until we finish collective bargaining. And I’m not leaving Starbucks, I’m not gonna do that. This is probably more meaningful than anything I’ve done in law school.”

Corporations have sought to weaken organized labor because they fear the power of the people united.

It remains to be seen whether the dominos will fall; if the successful unionization of one Buffalo Starbucks could lead to a country full of unionized coffee shops; if every corporation and industry will have its own set of dominos. From the moment a worker first contemplates joining a union, to the moment her union secures a first contract, corporate power will seek to undermine organizing efforts using every dirty trick in the book, and they will have the law on their side to back them. But the people will be there to meet them at every corner with a power of their own, and we have strength in numbers.

![[F]law School Episode 5: The Business of Boredom](https://theflaw.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/Reed_1-640x427.jpg)