Image taken by Grace Shrestha from the New Zealand House & Garden Magazine issue titled “Fresh Horizon.”

To the Art Institute, returning artifacts or disclosing the name of the donor of a “deaccessioned” artifact, may seem like institutional suicide. As Christie’s auction house reminded its patrons, “staying profitable is the only way for a museum to keep its mission alive.” “You want to keep your donors happy… Museums have to be cautious. Where are they going to be getting their money?” KT Newton explained.

If the Art Institute were to repatriate the Taleju necklace and share its illicit history, it not only risks losing the Alsdorfs’ support but also losing funding and partnerships from its current and future donors. Not only did the Alsdorfs build generational wealth and fame with the Taleju necklace’s donation, but so too has the Art Institute.

“Staying profitable is the only way for a museum to keep its mission alive.”

Since the Alsdorfs’ massive donation, the Art Institute has “expanded the collection in all areas.” The museum accepted a $75 million grant in September 2024, in part from Harvard Law School graduate, Aaron Fleischman, to build the “Aaron Fleischman and Lin Lougheed” building. The Bucksbaum family also gifted the museum $25 million in February 2024 to create the Bucksbaum Photography Center. Perhaps, if the museum had brought negative attention to the Alsdorfs after opening a gallery in their name in 2008, donors like Fleischman and the Bucksbaums would not have reneged on their deals.

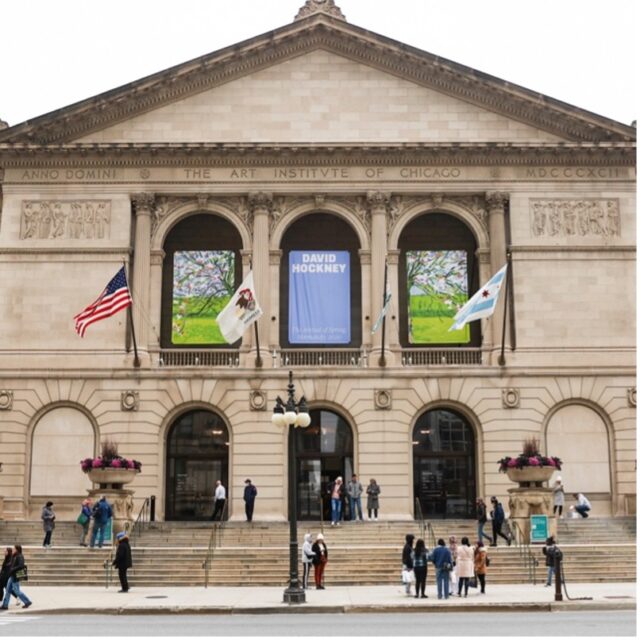

The Art Institute by day. Image taken by Grace Shrestha and provided by Wikipedia.

The Art Institute obtains hundreds of thousands of dollars from foundations, corporations, individuals, and universities. Thus, as Christie’s characterized, “even though [museums] are considered nonprofits… in actuality, without the business world, they wouldn’t exist.” Museums, like corporations, may be incentivized to engage in the notorious business practice of “artwashing.” Big Oil and the Arts author, Mel Evans, defines artwashing as using philanthropy to obtain a “social licen[s]e to operate,” cleanse a corporation of its unethical practices, and persuade the public that it is a “responsible benefactor.”

The Alsdorf Galleries” inscribed on the wall at the Art Institute of Chicago. Image provided by Erin Thompson.

For instance, the Sackler family’s donations to museums and universities, including the Art Institute of Chicago and Harvard Museums, may have intended to “wash” away their role in the opioid crisis through their business, Purdue Pharma. As Keefe explained, “the crude origins of any given clan’s largesse might be forgotten [when] future generations would remember only the philanthropic legacy, prompted [by] the family’s name on some gallery, some wing, or perhaps even on the building itself.”

In delaying or denying repatriation and concealing their donors’ involvement in the illicit trade of artifacts, the Art Institute preserves existing systems of power but claims to be righteous and trustworthy. Much of the American public seems to buy this narrative. They considered museums to be the most trusted sources of information in the U.S. in 2021 because they are “neutral” and “fact-based.”

The Institute of Museum and Library Services champions museums as “trusted places that support… our democratic society” and “drivers of educational, economic, and social change.” Despite controversy about its artifacts, the Art Institute was the top ten most-visited museum in the U.S. in 2023.

In delaying or denying repatriation and concealing their donors’ involvement in the illicit trade of artifacts, the Art Institute preserves existing systems of power but claims to be righteous and trustworthy.

The Art Institute of Chicago has made clear that it is willing to sacrifice the soul of a nation to maintain its funding and its reputation. The Alsdorfs’ philanthropy may have been foundational to the Art Institute’s growth, possession of show-stopping artifacts like the Taleju necklace, and long list of sponsors and donors: the University of Chicago, Bank of America, the MacArthur Foundation, and Allstate, to name a few.

The Art Institute may fear that surrendering the Taleju necklace would commence a donor death spiral. Yet, why place the donation of the king and “queen of the Chicago arts community” above the ancient offering of King Pratap Malla to Taleju Bhawani? As Uddhav surmised, “definitely money.”

“Doing God’s Work”: Collector as Savior, Museum as Temple

A dominant narrative that perpetuates the illicit antiquities trade is that art collectors, dealers, and museums “save” developing countries from the destruction and mismanagement of their artifacts. These high net-worth individuals and respected institutions often claim to have given or received artifacts in good faith, unaware of how they may have brought into the U.S.

The Art Institute may fear that surrendering the Taleju necklace would commence a donor death spiral. Yet, why place the donation of the king and “queen of the Chicago arts community” above the ancient offering of King Pratap Malla to Taleju Bhawani?

When the Taleju necklace disappeared in the 1970s, “it was a ‘no questions asked’ market,” in which dealers, collectors, auction houses, and curators turned a blind eye to the potential theft and trafficking of an artifact in their possession,” described Erin Thompson.

Elites in the art world often blame local communities in developing countries, like Nepal, for the loss of their cultural heritage. KT Newton describes that many of these elites claim, “it will be better protected here; we are a better receptacle, a better caretaker.” They attribute locals’ failure to lock up and maintain security guards to protect ancient jewels, sculptures, and paintings to antiquities theft and trade.

Nepali locals create floral garlands and red paste from vermillion powder

to adorn the statutes of gods and goddesses. Image taken by Grace Shrestha.

They point to locals’ use of the artifacts in their rituals, including decorating them with red and yellow vermillion pigments, flowers, and fabric, as the reason for the deterioration of artifacts. Museums and galleries have become like temples, constructed as safe, sacred spaces and hallowed halls where artifacts are better kept.

The Taleju necklace never needed rescuing. The Nepali community believes that the goddess herself, Taleju Bhawani, protects their country. It was the Western world that tried to convince them that Nepal cannot manage its own cultural property.

However, legitimizing the possession of Nepali cultural artifacts in these ways is a symptom of Western, colonialist assumptions and a misunderstanding about the meaning of cultural heritage to Nepal. While art collectors and dealers think that they are “saving” developing countries, they instead place communities in peril.

The people of Nepal view the sculptures of gods or goddesses and accessories as vital participants in rituals and community life, or part of their living heritage. “They have a life cycle, like us. We accept that they die and decay,” as Sanjay Adhikari explained. Taleju Bhawani Temple brings half a million Hindu visitors a year, who value its cultural significance rather than the objects inside.

The Taleju necklace never needed rescuing. The Nepali community believes that the goddess herself, Taleju Bhawani, protects their country. It was the Western world that tried to convince them that Nepal cannot manage its own cultural property. “Taleju Bhawani is angry that her necklace is gone. She wants it back. Nepal needs it back for national peace,” Uddhav emphasized.

Justifying the collection and distribution of Nepal’s artifacts based on the supposed good faith of art collectors, dealers, and museums ignores the negative consequences of their actions. Rather than doing Nepal a service, they have destabilized Nepal’s culture, identity, and security in showcasing a necklace that the world was never meant to see.

Nepali locals engaging in burning rituals in Kathmandu Durbar Square, where Taleju Bhawani Temple stands off camera. Image taken by Grace Shrestha.

Cultural Justice Delayed is Justice Denied

The U.S. requires that claimants in repatriation cases bear the burden of proving that an artifact in the U.S. belongs to them, yet this flawed system fails to account for global resource disparities. According to KT Newton, claimants must, first, “prove that the sale or export of the artifact occurred after their country’s patrimony law went into effect” and, second, produce provenance “documentation showing that artifact in the U.S. is the same as the one allegedly taken” (i.e., police reports, photographs, inventories, import paperwork).

However, locals in developing countries are often under-resourced and unable to find written documentation. In this case, “the provenance is hard to prove when Taleju Bhawani Temple is not open to the public, no photos or recordings are allowed, and the necklace was lost [fifty] years ago,” explained Sweta Baniya, a Nepali professor at Virginia Tech who has been a vocal advocate for the necklace’s return.

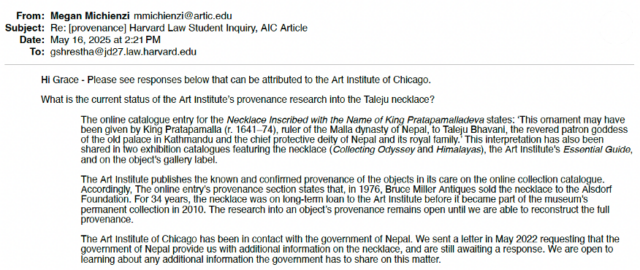

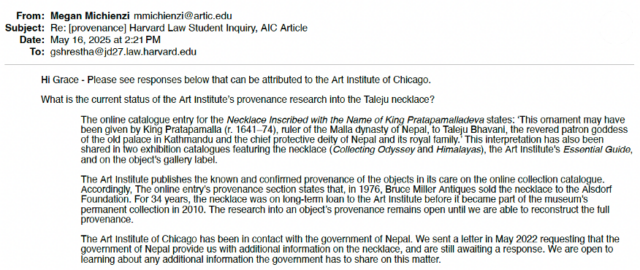

The Art Institute’s Executive Director of Public Affairs, Megan Michienzi, shared that the Art Institute “sent a letter in May 2022 requesting that the government of Nepal provide us with additional information on the necklace, and are still awaiting a response.” What Michienzi did not disclose was how detailed and nearly impossible the “additional information” that the Art Institute asked for is and continues to be for Nepal

The Art Institute replied to inquiries about the status of provenance research and the potential repatriation of the Taleju necklace with the statement that the provenance team is “still awaiting a response” from the Nepali government to its request for more information. Image taken by Grace Shrestha.

“The Art Institute sent the Department of Archaeology a statement demanding that we provide more evidence, like ‘records of the contents and history of King Pratap Malla’s royal collection,’” Sanjay Adhikari recalled with frustration. While Michienzi wrote that “[t]he Art Institute approaches the research, interpretation, and display of cultural objects with great sensitivity and care,” the Art Institute fails to acknowledge the difficulty for Nepal.

Among the big law firms defending major U.S. museums, like the Art Institute, against repatriation claims are Vault Law 100’s Munger, Tolles & Olson LLP and Venable LLP and Vault’s Best Law Firms in Boston, including Sullivan & Worchester.

The requested records are from the 16th century. The country that relies largely on the oral transmission of knowledge and history. Written documents often decay due to neglect or were destroyed during its civil war and political turmoil. Even surviving written records, as in the case of the Taleju necklace, may not be enough for the Art Institute to verify that an artifact was stolen from Nepal.

Meanwhile, art collectors, dealers, and museums are sophisticated, repeat players with a significant advantage in repatriation cases. These actors’ corporate lawyers cast doubt on the evidence that locals and activists produce.

Among the big law firms defending major U.S. museums, like the Art Institute, against repatriation claims are Vault Law 100’s Munger, Tolles & Olson LLP and Venable LLP and Vault’s Best Law Firms in Boston, including Sullivan & Worchester. These firms’ websites do not acknowledge the potential theft, trafficking, and trade that their clients engage in or perpetuate.

Instead, these firms refer to the “process of acquiring and selling art is multifaceted; it can be complicated and cloaked in mystery [so] [w]e assist in pulling back the curtain, negotiating and protecting our clients’ interests” and claim to understand the “challenges [] institutions and philanthropists face when organizing, funding and lending to public exhibitions.”

Museum provenance teams indicate a commitment to researching the origins of the pieces in their possession. However, as NHRC Vice Chairperson Kanak Mani Dixit has noted, such actions may in fact be “a delay tactic to wear down campaigners.”

The Art Institute has one of the largest provenance teams in the world, which it expanded between 2020 and 2024 to include more dedicated staff members. In August 2024, it appointed a new executive director, Jacques Schuhmacher, who claimed to be “thrilled to… continue this exceptional commitment to provenance.”

Yet provenance research may not be the most efficient solution to the injustice of cultural heritage loss when it has failed to bring the Taleju necklace home despite years of research and controversy. Uddhav and the Nepali community have waited too long to reunite Taleju Bhawani and the people of Nepal with the Taleju necklace and to feel more protected and peaceful.

Shifting the Burden and Changing Assumptions

While there is less hope for the Taleju necklace’s homecoming under current provenance practices, shifting the burden of proof onto possessors and requiring the voluntary repatriation of Nepali artifacts may prove to be a swifter solution that addresses the structural causes of cultural heritage loss and deprivation.

Changing the analytical framework in repatriation cases will account for the neocolonialist practices that fostered cultural heritage loss in the first place and the baseline inequalities that make it so difficult for individuals in developing countries to prove the theft and trafficking of antiquities centuries later.

However, relieving developing countries of the unfair burden of proof and instead requiring more sophisticated, well-resourced parties, possessors, to produce evidence will turn this illusion of legitimacy on its head.

Miller, the Alsdorfs, and the Art Institute captured and traded the soul of a nation for self-preservation. Bruce Miller commodified Asian culture and funded his lavish lifestyle, the Alsdorfs legitimized their purchases as patronage and philanthropy, and the Art Institute operated to preserve the power and trusted reputation of the Alsdorfs and the Art Institute itself.

However, relieving developing countries of the unfair burden of proof and instead requiring more sophisticated, well-resourced parties, possessors, to produce evidence will turn this illusion of legitimacy on its head. As Sanjay Adhikari has long advocated, the onus should not be on Nepal, whose “lack of resources is what motivated theft and trafficking in the first place.”

Furthermore, given that the ownership history of many artifacts remains impossible to reconstruct, a presumption of repatriation to the country of origin is necessary for equity. While the Art Institute and museums across the country have developed “much larger provenance departments” in response to increasing repatriation claims, as KT Newton noted, developing countries are at a disadvantage upon raising repatriation claims and the system has to change to account for that fact.

As Erin Thompson and NHRC Heritage Campaign Director Alisha Sijapati proposed in “Making a Market for ‘The Art of Nepal,” “voluntary repatriation for a cultural artifact with gaps in its ownership history” should occur when “1) there is little to no probability that these gaps can be filled by further research and 2) it is more probable than not that the unknown transfers were illicit.” When communities have sought to piece together an artifact’s history for years, possessors have a duty to repatriate and to repair the harm: a country deprived of nationhood.

Michienzi, on behalf of the Art Institute’s team, countered this equitable framework with the statement: “[i]t is important to understand that a provenance gap does not indicate anything. A provenance gap simply means there is a gap in our current knowledge about the object, a gap that we hope we will be able to fill with additional research.”

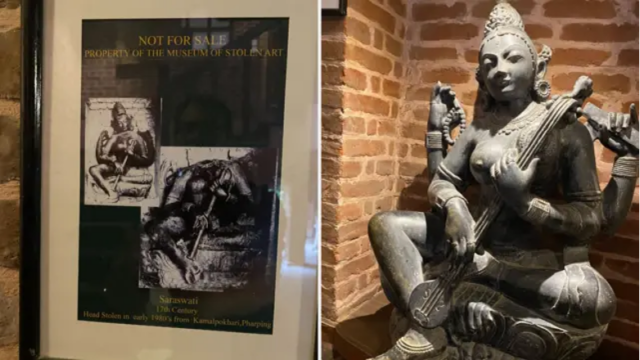

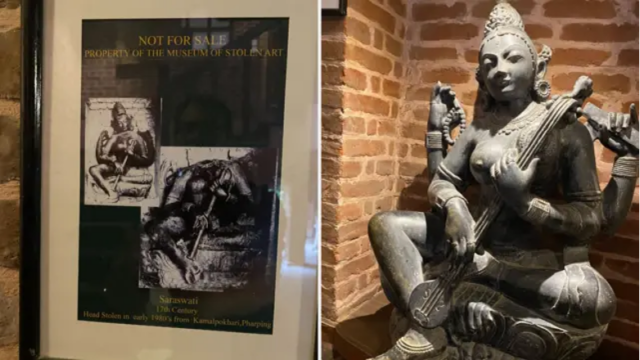

LAN and the NHRC have utilized technology to identify Nepali artifacts around the world, but Nepali people have also thought of other innovative ways to support museums in the repatriation process. NHRC Conservation Architect, Rabindra Puri, teamed up with craftsmen in Nepal to create a Museum of Stolen Art in Nepal with 45 replicas of Nepali artifacts that are on display in museums around the world. Nepal has a collection of artifacts ready for replacement.

A statue of a deity at Nepal’s Museum of Stolen Art. Image taken by Sanjaya Dhakal of BBC Nepali.

With the fourth-year anniversary of Uddhav’s discovery of the Taleju necklace this June 2025, its repatriation is long overdue. Perhaps returning it, being transparent about its history of pillage and trade, and commissioning Nepali people to create replacements will subject museums and donors, including the Art Institute and the Alsdorfs, to increased scrutiny and reputational loss. Yet would that not change how art market actors approach art collecting, selling, and viewing for the better?

Through this process, the U.S. can make reparations for centuries of neocolonialism and redistribute property to those who need and value it most. With regard to the Taleju necklace, that is, first and foremost, the Nepali people.

Art collectors may demand more information from dealers, galleries, and auction houses prior to the acquisition of artifacts to lower the risk of future controversy, which may disincentivize art dealers from trying to sell artifacts without disclosing sufficient details as to how they obtained them. Museums may assess the artifacts offered for loan or donation with more scrutiny and begin provenance research before accepting artifacts and creating galleries in donors’ names, as they know that they carry the burden of proof in future repatriation cases.

Such voluntary repatriation and replacement can redefine what it means to be a “philanthropist” and a “trusted institution” in the art world. Instead of building a reputation by taking and withholding, art dealers, donors, and possessors will do so in giving back what more likely than not illicitly arrived in their hands. Through this process, the U.S. can make reparations for centuries of neocolonialism and redistribute property to those who need and value it most. With regard to the Taleju necklace, that is, first and foremost, the Nepali people.

![[F]law School Episode 6: The Corporatization of Drag](https://theflaw.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/Burns_FeatureImage-640x427.jpeg)