A relic of the seventies

Certificate of need laws became widespread in the 1970s, after a Congressional mandate required states to adopt CON laws in order to qualify for certain federal funds. Forty-nine states—all but Louisiana—complied.CON laws were intended to control the growth of healthcare costs. Policymakers theorized that hospitals had insufficient incentive to compete over prices because most patients were insured, and therefore unresponsive to changes in cost. Meanwhile, providers would tend to overprescribe, knowing they would be reimbursed for expenses. This “third-party payer” problem was thought to lead to redundant, duplicative services that overburdened insurers and made healthcare more expensive for everyone.

An illustrative hypothetical: suppose a city has two hospitals, A and B. Hospital A buys a brand-new, expensive MRI machine, which is sufficient to meet patients’ needs throughout the city. But now Hospital B is at a competitive disadvantage for patient testing—so it buys an MRI machine, too. Now both MRI machines are underutilized, and the cost of keeping both running will be passed off on consumers through insurance premiums and taxes.

An MRI machine. Photo from Pixabay.

In theory, CON laws allow state regulators to prevent this kind of wasteful duplication. Before approving a new service, state regulators can assess the need in the community to ensure new services are actually responding to demand. But that approach has theoretical problems of its own.

First is the basic principle of supply and demand: if demand for healthcare remains fixed, but state regulators constrict supply, healthcare costs will rise.

Second is the problem of monopolization. If existing hospitals have limited competition, they can extract “rent,” charging higher fees than insurers or patients would normally accept. They may also engage in inefficient rent-seeking behavior—such as lobbying legislators and petitioning regulatory bodies—in order to preserve their hold on the market.

Federally, CON’s skeptics eventually won the day. Congress repealed the mandate in 1986. Two years later, the FTC issued a report finding that CON laws had failed to contain costs. More recently, the FTC and the Antitrust Division of the DOJ issued a joint statement condemning CON laws and warning about their anti-competitive effects. But the majority of states have ignored this warning.

The data show that CON is, at best, a failure. At worst, it is an expensive and burdensome restriction that hurts patients and undermines its own goals.

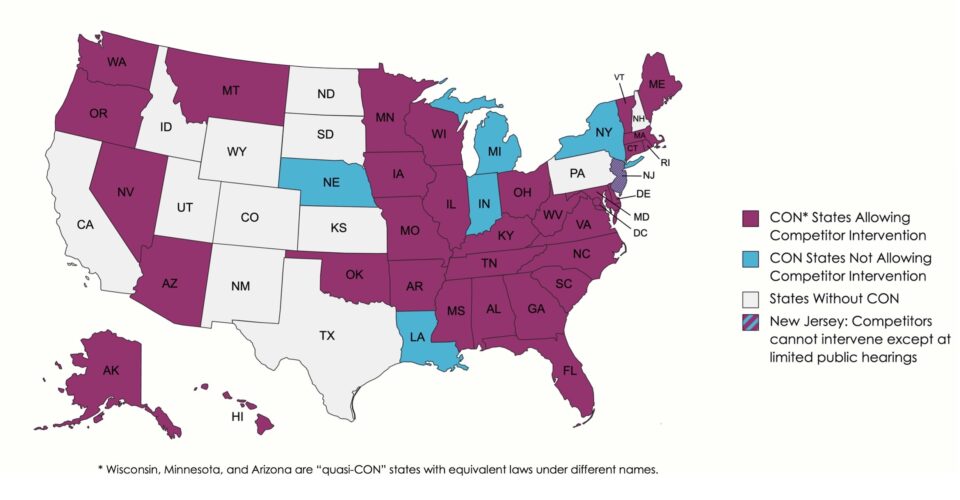

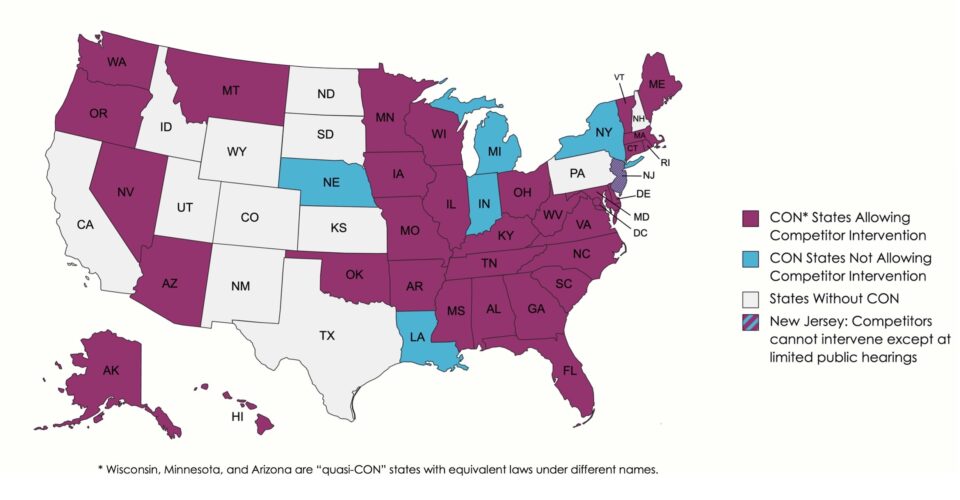

Today, thirty-five states and the District of Columbia require a certificate of need for a variety of medical services. A majority of those jurisdictions allow hospitals to intervene against their would-be competitors. Meanwhile, an eclectic minority of states—including California, Texas, and Pennsylvania—has proceeded without any CON regulations at all.

The result is a nationwide, forty-year-long experiment pitting states that retained CON against those that repealed. The data show that CON is, at best, a failure. At worst, it is an expensive and burdensome restriction that hurts patients and undermines its own goals.

“This is a phenomenon that has been extraordinarily well studied,” says Matthew Mitchell, an economist at West Virginia University who has authored several reports on CON laws. “Four out of every ten Americans lives in a state without a certificate of need law. We can look and see what’s happening to patients’ costs and quality in those communities relative to patients where CON is maintained.”

Out of 37 studies Mitchell has analyzed, 26 found that CON is associated with increased per-service healthcare spending. A majority of studies on per-capita spending show a similar trend. And 55% of studies that have examined quality-of-care find that CON states have lower quality services, compared to only 8% that find higher quality associated with CON.

Most damningly, “the evidence is pretty overwhelming that CON leads to significantly fewer resources and availability of resources,” Mitchell said. “82% of the studies that have assessed the effect of CON on availability or access to care find that it’s associated with less.”

Access is especially diminished for vulnerable populations, compounding the harms of poverty and inequality. “If anything, rural communities—which were specifically singled out by the authors of the [original Federal CON mandate]—seem to be worse off because of CON.” Similarly, “there’s greater racial disparities in provision of care in CON states relative to non-CON states.”

CON’s failure on display

The consequences of CON can be observed throughout the country.

In Georgia, Black women are 50% more likely to die in childbirth than white women. The disparity coincides with a large overlap between majority Black counties and maternity care deserts, where there are no birth centers or facilities offering obstetric care.

Despite the disparity, Georgia’s CON law forces new birth centers to survive an exacting review process and secure a transfer agreement with a local hospital. In one recent case, reported in Capital B News, three hospitals exploited that requirement to block a proposed birth center from opening in the majority-Black city of Augusta. The surrounding rural counties—which the birth center was intended to serve—form one of the largest maternity care deserts in the southeastern United States.

In Kentucky, Nepali immigrants Dipendra Tiwari and Kishor Sapkota formed Grace Home Care, hoping to provide more personalized home health services for Louisville’s large Nepali-speaking community. They were shocked to discover that even though they would be working within patients’ homes—not opening a facility with inpatient beds—they would still need to pay a $1000 application fee and submit to a 90-day review process. When they did, a regional health conglomerate intervened in opposition and convinced Kentucky to reject the application. Tiwari and Sapkota challenged the decision in federal court, arguing that by favoring monopolistic incumbents, Kentucky’s CON law violated their Constitutional due process and equal protection rights.

“We weren’t even suing about a service the hospitals were interested in protecting. Their interest is just in protecting certificate of need generally.”

To their dismay, the Kentucky Hospital Association intervened in the lawsuit on behalf of the state, despite having little to gain from blocking Grace Home Care. “Most hospitals in the state don’t have home health agencies,” said Jaimie Cavanaugh, Tiwari’s and Sapkota’s lawyer in the lawsuit and co-author of a detailed report on CON laws. “We weren’t even suing about a service the hospitals were interested in protecting. Their interest is just in protecting certificate of need generally.” The hospitals won—the district and appellate courts upheld Kentucky’s CON law, and the supreme court declined to hear the appeal.

Hospitals continue to recite arguments that decades of research have debunked—CON laws are justified because they lower costs, increase quality, and broaden access to care. That these claims are false is no obstacle, because Federal courts apply rational basis review to economic liberty claims. That means courts will uphold an economic regulation so long as the judge can imagine any rationale for the law—even if that rationale was never supplied by legislators, was premised on a falsehood, or employed faulty logic.

In upholding Kentucky’s CON law, the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals acknowledged “considerable evidence showing that, in practice, certificate-of-need laws often undermine the very goals they purport to serve,” and that “the judgment that this was a failed experiment has the ring of truth to it.” Chief Judge Jeffrey Sutton insisted there was a rational basis anyway, without citing any research in support: “the State could plausibly think that the certificate-of-need program would increase quality in one way or another.”

A map of CON across the country. Data from Conning the Competition by Jaimie Cavanaugh et al. Created with mapchart.net.

For state claims, the bar is sometimes higher, but still easy for the defense to clear. For instance, North Carolina’s Supreme Court once ruled that CON laws violate the due process and anti-monopoly provisions of the state constitution. The state legislature simply reenacted the law four years later, with findings of fact reciting the now-familiar spurious arguments about cost and access. North Carolina courts have upheld the revised law, even as decades of evidence have cast doubt on its stated rationale.

Recently, a North Carolina ophthalmologist named Jay Singleton was barred from performing surgeries at his own outpatient facility because state regulators had determined there was no need for new operating rooms. Rather than submitting a futile application, he sued the state. But the district court dismissed his suit and the court of appeals affirmed, holding Singleton needed to bring his complaints to state regulators first.

Renée Flaherty, an attorney at the Institute for Justice who represents Dr. Singleton, has hope that the Supreme Court will restore its prior ruling and enforce the state constitution’s antimonopoly provisions. Until then, the prospects for independent doctors are bleak.

“There’s this whole cottage industry that has grown up surrounding [CON]. There are lawyers and consultants who just know how to go through this process, and if you can afford to hire them, you can get through.”

By leveraging their resources and lobbying state legislators, hospitals can make sure regulators never recognize any “need” for independent doctors to fill. “And if a need does pop up,” Flaherty said, “you basically know who is going to get it.”

A captured industry

By allowing incumbent hospitals to intervene against potential competitors, CON laws create a profound conflict of interest for health regulators. This makes the state agencies that enforce CON especially vulnerable to capture.

“Their thinking is they need to make sure that the hospital is flush,” Doctor Halliburton said, referring to Vermont’s Care Board. “They should see their job as being regulators of the hospital and making sure patients can afford access.” Instead, the regulators “feel they’ve done a good job if they let the hospital get away with a 7% [price] increase instead of a 10% increase.”

Halliburton thinks the favoritism is no coincidence. “If you work for the government or the Care Board or an insurance company, and you do something favorable towards the hospital, within a few years you will likely find those people employed in a very cushy position at the hospital.”

One prominent example is Albert Gobeille, the local businessman who chaired the Care Board throughout UVM Health System’s rapid expansion, and later served as Vermont’s Secretary of Human Services under governor Phil Scott. He oversaw the delays that hampered GMSC, and provided fuel to their skeptics in public statements. “He was vehemently opposed to [Dr. McCormick’s] eye center that never got built—and ours,” Halliburton recalls, adding that Gobeille “publicly would trash us any chance he got.” In 2019, UVM Health System appointed Gobeille to the newly-created position of Executive Vice President. Gobeille could not be reached for comment.

“If you work for the government or the Care Board or an insurance company, and you do something favorable towards the hospital, within a few years you will likely find those people employed in a very cushy position at the hospital.”

Executive pay may be a major incentive for hospitals’ anticompetitive practices. One study found that CON laws enable urban hospital CEOs to extract higher salaries by a margin of $91,000 per year. That figure may understate the problem—hospital CEOs are already the highest-paid nonprofit executives across all industries, and leaders of the largest hospitals supplement their salaries with multi-million-dollar bonuses. The CEO of UVM Health System took home $2.2 million dollars in 2016—$979,064 in salary plus a $1.3 million dollar bonus. These executives populate the boards of Hospital associations, where they can exert coordinated influence on state regulators.

Hospitals like UVM Medical Center often tout their charitable purposes in contrast to the for-profit structure of physician-owned practices like GMSC. But despite their tax status, nonprofit hospitals across the country have taken on an eerie resemblance to private corporations. They are merging into ever-larger organizations, even as experts warn that increased consolidation will inflate costs and decrease access. They employ highly-paid CEOs and administrative officers, whose paychecks are growing faster than those of even the best-compensated doctors. And increasingly, they are spending millions of dollars each year lobbying state legislatures to kill healthcare reforms they don’t like.

“They had someone in Montpelier all the time,” Halliburton said, referring to the Vermont state capital. “Lobbyists basically twenty-four-seven, every day of the week, every day of the year.”

In front of legislatures, hospitals portray themselves as helpless, cash-strapped charity organizations who depend upon profitable services in order to stay in business. Jaimie Cavanagh, who has advocated for CON reform in state legislatures, recounts a particularly extreme form of this argument: “they literally say, in public and on the record, if you repeal certificate of need laws, our patients will die.”

“They had someone in Montpelier all the time,” Halliburton said, referring to the Vermont state capital. “Lobbyists basically twenty-four-seven, every day of the week, every day of the year.”

Matt Mitchell gives a somewhat more charitable explanation. “This may be the best argument I’ve encountered for CON. [Hospitals] will say we’ve got these big unfunded regulatory mandates [like EMTALA] that say if somebody walks through our door, we have to provide emergency care. Little ambulatory surgical centers that cater to, frankly, well-off seventy-year-olds with knee problems don’t have to comply with those.” Hospitals claim that this disparity will allow small surgery centers to syphon off their profitable procedures and drive hospitals out of business. “That argument definitely goes a long way with a lot of legislators.”