Consumer Protection: A Eulogy

Trump’s Efforts to Dismantle Consumer Protection

Carson Whitesell

May 17, 2025

Imagine a YouTube channel full of videos created by financial experts with titles like “Five tips for when you can’t pay your bills,” “Beware of scams related to the coronavirus,” “How do I dispute an error on my credit report?” and “How can I improve my credit scores?” That YouTube channel existed and was run by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), an independent agency in the federal government. Since January, however, every one of those videos (and many more) has been deleted by the Trump administration. The YouTube channel is now completely empty.

A helpful YouTube channel was not the CFPB’s only way of helping Americans. This past December, the agency finalized a rule that would cap most overdraft fees (fees charged when a purchase is made that exceeds the account balance) at $5. It estimated that this cap would save American consumers $5 billion in fees per year. Overdraft fees are disproportionately paid by low-income families, so those savings would mostly benefit America’s most financially vulnerable populations.

In late March, the Senate passed a resolution by a vote of 52-48, almost entirely along party lines (the only Republican to vote against was Missouri Sen. Josh Hawley), striking down that rule. The House passed the resolution—again along party lines—in early April, and it now sits on President Trump’s desk waiting to be signed.

Why would Republicans vote against saving their constituents money? Tim Scott—South Carolina Republican, Chairman of the Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs, and sponsor of the Senate resolution—said that capping fees would limit banks’ ability to allow consumers to overdraw their accounts. While overdraft fees make up a large source of revenue for banks, that revenue has significantly declined each year since 2019. In total, overdraft fee revenue has more than halved, dropping from almost $12 billion in 2019 to $5.8 billion in 2023.

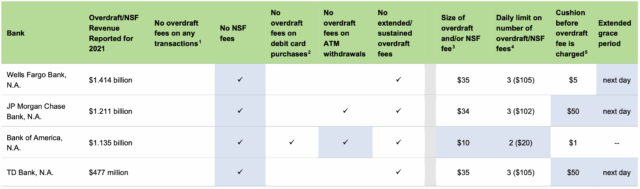

This drop is due in large part to a few banks deciding to reduce or eliminate overdraft fees because of increased scrutiny from the CFPB. Capital One and Citibank, for example, have completely eliminated overdraft fees. Bank of America reduced its overdraft fee to $10 and now offers a type of account with no overdraft fees at all. These banks still allow their customers to overdraw their accounts and can do so without losing money by restricting future overdrafts if the balance isn’t paid within a certain amount of time. These banks’ choices to reduce fees show that contrary to Tim Scott’s declaration, capping these fees would not create a substantial burden to banks’ ability to allow overdrafts.

Further, although some banks have taken these steps toward “financial inclusion,” not all have. Most large banks still have overdraft fees over $30, which can be charged multiple times per day. The CFPB’s regulation, then, would help protect low-income accountholders at these banks from incurring potentially hundreds of dollars in fees per year. Even those banks that have reduced fees did so in part because of the CFPB’s pressure.

Overdraft data on the four largest banks in America. The CFPB website includes data on the twenty largest banks. Source: Consumer Financial Protection Bureau.

While Congress’ resolution to strike down the regulation is a prime example of undue deference to banks’ complaints, this is just the latest step in a large, concerted effort by Republicans to shut down the CFPB.

To understand why Congressional Republicans and the Trump administration are deleting YouTube videos and striking down money-saving rules, it’s helpful to start with the 2008 Financial Crisis.

Too Big to Fail

In 2007, then-Harvard law professor Elizabeth Warren wrote an article outlining an idea for a financial regulatory agency that would protect low-income and middle-class consumers from predatory and unsafe financial practices. After the 2008 Great Recession, it became clear that the largest economic downturn since the Great Depression was caused by irresponsible behavior by large banks. These banks engaged in incredibly risky lending practices, investing enormous amounts of money into high-yield bonds backed by particularly risky home mortgages (the 2015 film The Big Short explains these complicated concepts quite well).

After Lehman Brothers collapsed in 2008, the federal government spent billions of dollars to stabilize the financial system, including by bailing banks out of the debt their poor decisions had created. The uproar over these bank bailouts at taxpayer expense (many of which have still not been repaid) led to the creation of a new, independent financial regulatory agency based on Warren’s idea. Congress passed the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act in 2010, largely along party lines.

The uproar over bank bailouts at taxpayer expense led to the creation of a new, independent financial regulatory agency based on Warren’s idea.

The Act imposed regulations and reforms on major banks and financial institutions intended to lower the risk of the type of broad systemic failure that caused the Great Recession. It created the CFPB to combat mortgage fraud and other abusive practices by the financial industry. It did, though, contain compromises that reduced the CFPB’s regulatory power from what Warren envisioned.

Warren imagined a regulatory body that would play a similar role for financial products that the Consumer Product Safety Commission plays for tangible goods like toasters. Her paper opened with a now-classic example: consumers are unable to buy a toaster with a one-in-five chance of spontaneously combusting because the Consumer Product Safety Commission and other regulatory bodies impose strict safety regulations before products ever hit the shelves. No such protections exist for financial regulations, though. A risky, predatory mortgage could have a one-in-five chance of putting a family on the street.

Similarly, regulations don’t allow toaster prices to be changed after it has already been purchased. Long after you sign a mortgage, however, the bank can triple the price of the credit used to finance the purchase, even if the buyer has met all the credit terms.

In Warren’s original vision, the CFPB (or her version of it) would impose safety regulations on financial goods (like mortgages, loans, etc.) before banks could offer them to consumers. They would check the terms of these financial products, ensuring there were no hidden tricks or traps that would make them more financially dangerous than consumers realized.

In the Treasury Department’s proposal in June, 2009, however, they replaced this pre-clearance scheme with a “plain-vanilla” products scheme. Under Section 1036 of the proposal, the CFPB could require banks and financial organizations to offer financial products or services in a basic, so-called plain-vanilla form. These plain-vanilla products would pose lower risks to consumers through simple, more favorable terms with adequate transparency for consumers to understand their terms. Consumers must have a “meaningful opportunity to decline” plain-vanilla products before they can be offered alternative products (such as adjustable-rate mortgages, complex derivatives, and other more complex financial products).

The plain-vanilla scheme was a weakened replacement for Warren’s imagined pre-clearance, but even it did not survive Congress. When the CFPB was created by the Dodd-Frank Act, it had neither pre-clearance nor plain-vanilla powers, severely limiting its regulatory powers. Additionally, under the 2009 proposal, the CFPB would have been led by a five-member Board with four of the members appointed by the President. Instead, Congress gave the agency just a single director.