Despite the MSC’s purported commitments to sustainability, human rights and environmental groups have criticized much of its decision-making, arguing the MSC is not effective at regulating the sustainability of fisheries. A chapter of the Sierra Club, several European WWF offices, and Greenpeace have all criticized the MSC for certifying specific problematic fisheries. Further, over half of MSC-certified “sustainable” tuna is caught with controversial fish aggregating devices (FADs). FADs are floating structures placed in the ocean to catch fish, which many environmentalists view as unsustainable because they can trap bycatch, such as sea turtles and sharks.

Because the Marine Stewardship Council is designed to protect fisheries, not people or fish. The seafood industry is the main financier of the MSC, so, of course, the nonprofit does not fight for what would actually benefit the seas.

Why has the world’s preeminent ecolabeling nonprofit gone against the advocacy of leading human rights and environmental groups? Because the Marine Stewardship Council is designed to protect fisheries, not people or fish. The seafood industry is the main financier of the MSC, so, of course, the nonprofit does not fight for what would actually benefit the seas.

According to the MSC’s website, 88.7% of the MSC’s income comes from “charitable activities (logo licensing).” This statistic indicates that most of MSC’s funds come from the seafood industry, which pays to use the blue MSC logo. In other words, the groups paying for MSC certification, the seafood industry, are the exact same groups keeping MSC in existence.

This funding structure may deter MSC from providing important information to consumers who trust its logo. For example, the seafood industry relies heavily on enslavement and forced labor. The seafood industry’s influence is likely part of the reason MSC largely ignores these human rights abuses in its certification process. If MSC prioritized the people and ecosystems harmed by the seafood industry, the nonprofit’s budget would take a massive, likely irretrievable, hit unless it found another funding source.

The Marine Stewardship Council is not unique among nonprofits. Despite not being profit-driven, many nonprofits rely on and are beholden to corporations and the ultra-wealthy.

Across the globe, corporations and the ultra-rich capture charity and the work of nonprofits. In this article, I delve into the long history of how the ultra-rich leverage charitable giving for their own financial benefit. I then analyze how corporations co-opt nonprofit missions to their advantage. I continue by discussing the more subtle ways corporations and the ultra-rich can change and erode the effectiveness and the mission of a nonprofit’s work. I conclude with a few ideas on how we move forward.

Nonprofits

According to the Center on Nonprofits and Philanthropy, the United States has approximately 1.8 million nonprofits. The most common type of nonprofit is known as a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, named after how it is organized under the U.S. tax code. These nonprofits are often referred to as charitable organizations or charities.

The defining trait of 501(c)(3) nonprofits is that they, as the name suggests, are not profit-seeking. They also face strict limitations on their political activities or lobbying efforts. If they follow these requirements, 501(c)(3) nonprofits are tax-exempt. Many charities, private foundations, universities, and churches are 501(c)(3) nonprofits. The U.S. recognizes several other types of nonprofits. However, this article will focus on 501(c)(3) nonprofits, which account for roughly 75% of the nearly $2 trillion in revenue and expenses from the nonprofit sector.

In 2022, donors gave $500 billion to U.S. nonprofits. About 64% of those donations came from individuals, 20% from foundations, 9% from bequests (donations made at death), and 6% directly from corporations. Further, about 33% of individual donations and 86% of bequests come from the top 1%. These donations come with enormous tax benefits, with individual donors being able to avoid taxes on up to 60% of their income by donating.

The Gilded Age(s)

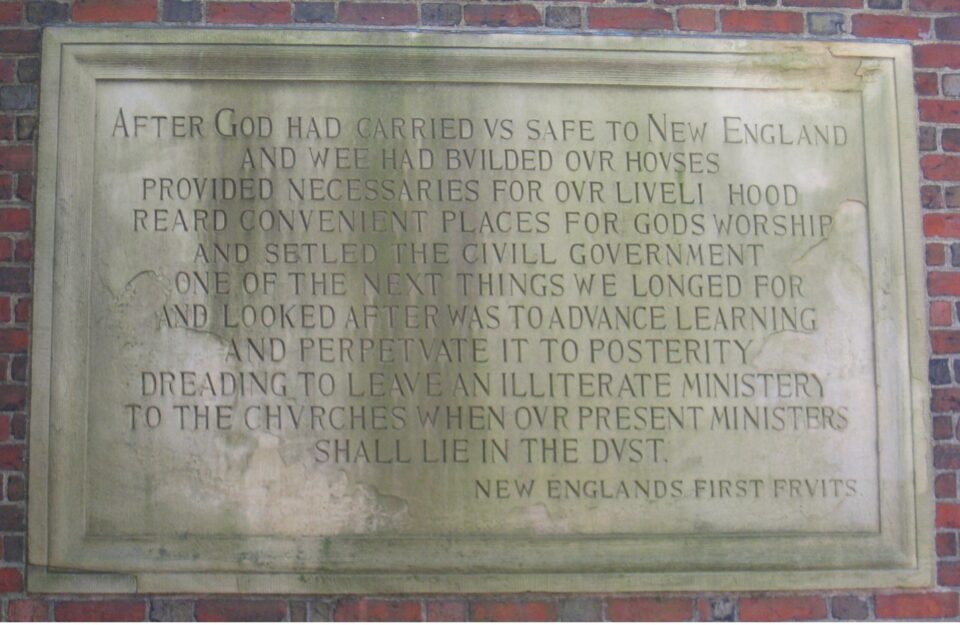

Andrew Carnegie may be the most influential philanthropist of all time. He donated more than virtually anyone else in American history, built nearly 3,000 libraries, started a leading research university, and founded over a dozen other nonprofits that still operate today. Further, in penning The Gospel of Wealth, he literally wrote the book on philanthropy in which he claimed: “the man who dies thus rich dies disgraced.”

According to Forbes, Carnegie remains the second richest person in American history, adjusted for inflation. His philanthropic ideals were certainly not what led him to such riches. Instead, Carnegie accumulated wealth by paying his workers poorly, forcing them to work 12 hours a day in dangerous conditions, and going to great lengths to sabotage their organizing efforts. Meanwhile, he alternated living in a literal castle in Scotland and his Fifth Avenue mansion.

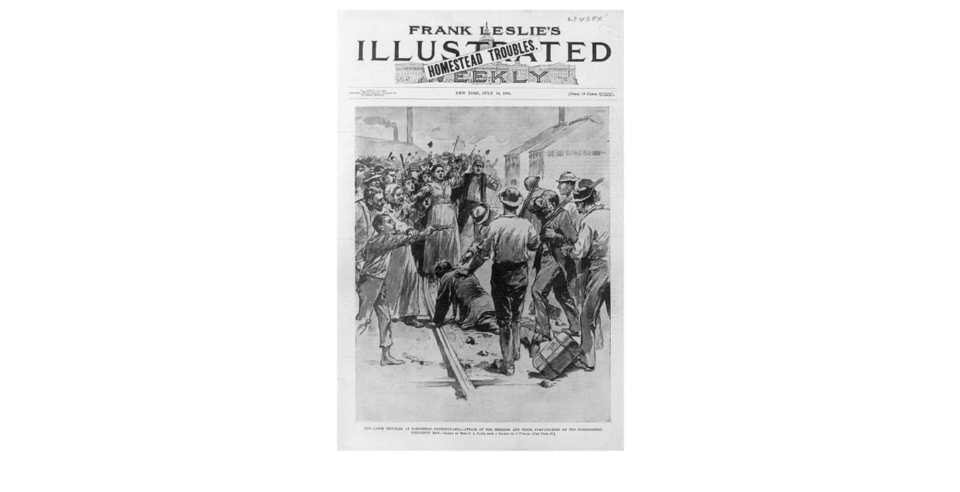

In 1892, his Carnegie Steel Company was making a record profit, which led Carnegie to reportedly proclaim, “Was there ever such a business!” However, Carnegie Steel, threatened by the company’s unionized workers and their (relatively) high pay, sought to destroy the labor organization. Carnegie Steel hired Pinkerton security guards at a steel mill near Pittsburgh, causing a confrontation later known as the “1892 Homestead Strike” that resulted in 16 deaths and the virtual destruction of the union.

A weekly newsletter depicting a seemingly violent interaction between the Pinkerton security guards Carnegie Steel hired and the striking workers. Source: Library of Congress.

Later in life, Carnegie ultimately gave away approximately 90% of his wealth by or after his death. In the end, he lived his life as he preached and was not the rich man who died “disgraced.” His thousands of libraries and many nonprofits surely have positively affected the world.

Elizabeth Kolbert, in her article “Gospels of Giving for the New Gilded Age,” highlights Carnegie’s disconcerting dissonance in asking, “[h]ow could a person ruthlessly exploit his employees and, at the same time, claim to be a benefactor of the toiling masses?” Similarly paradoxical, Carnegie’s Gospel of Wealth, though certainly pro-wealth redistribution, is full of dubious ideas, such as the idea that wealth naturally and justly accumulates into the hands of the few and that these few likely know best how to fight poverty.

Carnegie’s story leaves us with questions about how to approach philanthropy: Is the best model really one that requires someone to do heinous actions to be able to do good later? Do we really want the people willing to commit these acts to be the ones who decide what is “good?”

Kolbert argues we are yet again in a Gilded Age, and today’s ultra-wealthy have honed the philanthropy playbook Carnegie wrote. However, today’s billionaires are possibly no wiser and even less committed than Carnegie.

Is the best model really one that requires someone to do heinous actions to be able to do good later? Do we really want the people willing to commit these acts to be the ones who decide what is “good?”

For example, Bill Gates regularly ranks at or near the top of the US’s most philanthropic billionaires, as he did in 2021, 2022, and 2023. Like Carnegie’s approach before him, Gates’ business practices also included questionable attacks on unions. A court also ruled the company he founded, Microsoft, guilty of illegal monopolistic practices.

Bill Gates is not exceptional in his ruthless pursuit of wealth. Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos, one of the richest people on the planet, actively tries to bust potential unions that are organizing in response to harsh working conditions and high injury rates. Mark Zuckerberg treated the people around him so poorly that Hollywood made a movie about it. Starbucks billionaire CEO Howard Shultz is in the news every week for a new union busing tactic. The list goes on.

Apologists for the ultra-rich are quick to ignore the unethical and destructive ways billionaires accumulate their wealth, insisting they are the ones who can save us from the world’s biggest problems, like systemic injustice, climate change, or the proliferation of dangerous technology.

OpenAI: A Billionaire’s Relapse toward Profit

Ignoring billionaires’ pasts has admittable allure. Take Bill Gates again; all his unethical practices happened a decade, if not decades ago. These days, he’s known primarily as a philanthropist striving to save the world. Like Andrew Carnegie before him, Bill Gates may also appear to be a benevolent billionaire, committing himself and his foundation to improving global health and fighting climate change.

Yet, when recently confronted with a new, potentially world-altering problem, he again chose profits over the common good. Bill Gates is no longer involved in Microsoft’s day-to-day operations. Still, his endorsement led to Microsoft’s aggressively investing in generative Artificial Intelligence (A.I.), including in OpenAI, owner of ChatGPT.

The founders of OpenAI started the organization as a nonprofit “with the goal of building safe and beneficial artificial intelligence for the benefit of humanity.” However, after Microsoft began investing, OpenAI formed a for-profit company to help benefit Microsoft.

Partially in response to this development, members of OpenAI’s board, some of whom were with OpenAI in its earliest days, moved to oust OpenAI’s CEO, Sam Altman. The OpenAI board was alarmed because OpenAI’s technology poses a significant risk to the world, and Altman has been dismissive of the potential catastrophe that could result from A.I. Microsoft, which has now invested $13 billion in OpenAI, called for Altman’s return as CEO. Upon Altman’s return, the board members prioritizing humanity’s safety over profits were pushed out.

A.I. is still young and full of potential, both positive and negative. However, as long as philanthropists continue to operate as businesspeople, it will develop toward profit-making.

The Systemic Limitations to an Effective Nonprofit

The A.I. example drives home a key point: Billionaires and the ultra-wealthy will go to great lengths to protect their interests as the system changes. Billionaires have little, if any, incentive to fight, or support others in the fight, for positive systemic change. Instead, they donate significant portions (but never significant enough to undermine their power) of their money to fix individual inequities—inequities that their exorbitant accumulation of wealth played a role in creating. They then get to justify their obscene hoarding of wealth by saying that they are “giving back” and that we should trust them (and maybe even thank them). Typically, this practice obfuscates the issue enough that there is no real accountability and little work done addressing these issues on a systemic level.

The winners of our age must be challenged to do more good. But never, ever tell them to do less harm.

Anand Giridharadas, author of Winners Take All, captured this dilemma eloquently in a speech to the Aspen Global Leadership Network, saying the challenge to the rich, “in a nutshell, is this: the winners of our age must be challenged to do more good. But never, ever tell them to do less harm.”

The ultra-wealthy do not fight to upend systemic injustices. Instead, they use charitable donations to gain tax relief while making sure their donations go toward shaping public policy in a manner beneficial to them. In his book The Givers, David Callahan argues that the rich are masking their policy advocacy as philanthropy and benefiting from it in multiple ways. Callahan estimates that “a sum in the low billions” of philanthropic donations each year goes toward shaping public policy. This amount is “much more than the combined annual political giving to candidates, party committees, 501(c)(4)s [a political variant of a nonprofit], and super PACs.”

Kolbert argues this outcome is doubly undemocratic because these donations are tax deductible: “For every billion dollars spent on advocacy tricked out as philanthropy, several hundred million dollars in uncaptured taxes are lost to the federal treasury.” Callahan puts the issue concisely: “It’s not just that the megaphones operated by 501(c)(3) groups and financed by a sliver of rich donors have gotten louder and louder, making it harder for ordinary citizens to be heard. It’s that these citizens are helping foot the bill.”

Stanford Professor Rob Reich, in his book Just Giving, notes that in addition to “[t]ax incentives for philanthropy [being] one of the largest expenditures” in the U.S. tax code, this spending also does not go to those who need it most. Reich states, “at most one-third of charity is directed to providing for the needs of” those with limited means.

The ultra-rich seem to have captured the field of “charitable donations” to create tax subsidies for themselves and generate PR opportunities. They take advantage of this system without addressing the systemic issues that led to their wealth and power and largely refrain from helping those most in need.

Worse, rich people are less likely to help those most in need. Reich notes that “the inclination to give to help meet basic needs declines as one rises up the income ladder.” The ultra-rich appear to have captured the field of “charitable donations” to create tax subsidies for themselves. They take advantage of this system without addressing the systemic issues that led to their wealth and power and largely refrain from helping those most in need.

Giridharadas sums up these problems nicely, saying this form of giving “tries to market the idea of generosity as a substitute for the idea of justice.” The idea is to “make money in all the usual ways, and then give some back through a foundation, or factor in social impact, or add a second or third bottom line to your analysis, or give a left sock to the poor for every right sock you sell.”

Earth Day: Corporation’s Perfect the Strategy of Co-optation

As seen with the Marine Stewardship Council and OpenAI, the involvement of corporations and the ultra-rich can have pernicious effects on nonprofits’ work. In the MSC case, the conflicts of interest were obvious, with industry directly funding their work. In the OpenAI case, Microsoft pressured the nonprofit to start a for-profit arm. However, the same influences can affect other nonprofits in subtler ways.

During the first Earth Week (known today as Earth Day), Philadelphians showed up en masse. With an estimated 20,000 to 40,000 people in attendance, Philadelphia had one of the highest turnouts across the nation. In a city unflatteringly referred to as “Filthy-delphia,” the Earth Week Steering Committee, led by college students, obtained all the pollution data the city had and brainstormed how to use this information.

The Committee considered a direct attack on polluting industries in the city. However, they also needed money to fund a whole week’s worth of activities. An invite to discuss funding came from an unlikely source: the Chamber of Commerce, comprised of the businesses against which the Committee had considered direct attacks.

The Committee spent three days debating whether the group should even attend the meeting. They asked themselves questions such as whether accepting the money would lead to being “co-opted by business” and whether they “would be diluting [their] effort[s] completely.”

Ultimately, the Committee accepted money from the same businesses that had caused the problems they were protesting. In return for a $45,000 pledge, the Committee promised not to “sponsor marches and demonstrations against the industries.” Additionally, each sponsor would get a line in the official Earth Day program. Perhaps this alliance is why the idea of Earth “Week” never took off. Corporations discovered that co-opting Earth Day was more effective than fighting it.

According to former Senator Gaylord Nelson, who helped lead the movement, the original goal of the Earth Day movement was to “summon the public support, the energy, and [the] commitment to save our environment.” The movement helped inspire the passage of transformative environmental legislation.

Today, however, as Slow Factory, an environmental and social justice nonprofit, described, Earth Day may be better understood as “a greenwashing marketing stunt for brands to push their nonexistent sustainability.” Slow Factory is not alone in its skepticism. Other climate activists lament that Earth Day has become more about getting out into nature or shopping Earth Day sales than “protesting and demanding change on behalf of those being hurt by the climate crisis.”

With companies such as ExxonMobil unashamedly celebrating Earth Day, these climate activists have a point.

![[F]law School Episode 8: Selling Harvard Law Students](https://theflaw.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/Screenshot-2024-09-08-at-9.59.54 AM-640x427.png)