Unfortunately, bonds have failed to prevent abandoned wells due to flaws in their regulatory design and application. The BIA hasn’t raised the minimum bond rate —the amount lessee producers must set aside pre-production—since 1974 for leases on the Osage Reservation. Producers can get away with even lower rates by opting for “blanket” bonds, which cover a number of a company’s wells as opposed to single-well bonds. At this point, an already paltry sum undergoes further dilution—these bonds are often earmarked to fulfill a number of obligations beyond environmental compliance. Other costs include royalty payouts to the subsurface owner (here, the Osage Nation) or the land’s lessor, the reclamation of any “surface disturbances” that occurred during extraction, and a number of other creditors.

Companies are following the cues given by the system. It would be bad business to fully internalize costs, such as well capping, when a company is incentivized to neglect their environmental obligations and shift the cost to the public.

If the BIA were to impose higher minimum bond rates, single-well requirements, and heftier allocation requirements for capping purposes, such improvements could still fail. Companies, especially those facing insolvency, have little incentive to preserve their pre-production funds. The BIA has few means of enforcement. Instead, there is good reason for smaller producers to exhaust these funds during a well’s life cycle to meet rising production costs. To quote Chairman Waller, “it’s boom or bust here in the oil field.”

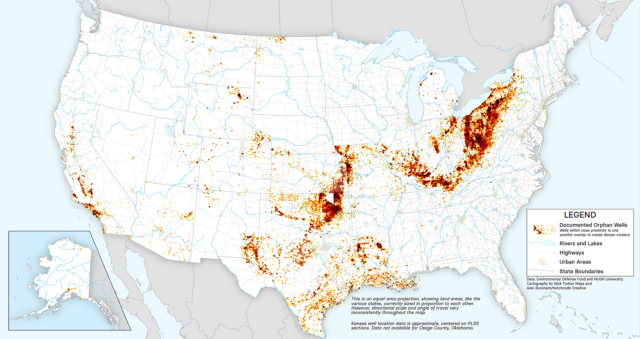

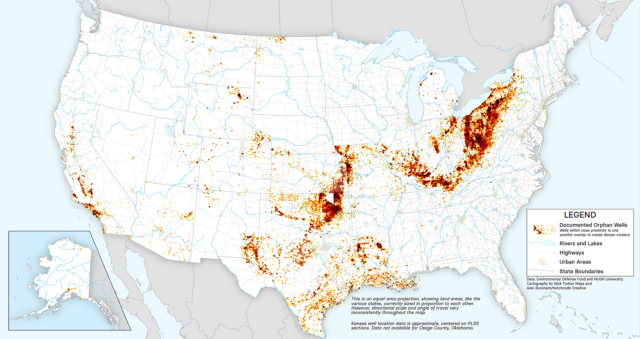

A map displaying the location of orphan wells across the United States, from the Environmental Defense Fund.

Decommissioning bonds are only part of the story of orphan wells, though. Defensive protections like bonds can do little when the larger systems of law and finance encourage “liability shedding.” A common cycle is as follows. First, larger companies sell their wells to a smaller producer when a well is about to become dry or less profitable. By transferring production and the attached lease, larger companies also rid themselves of the cleanup responsibilities. Then, the small producer often cannot afford the operating costs of an unprofitable well and declare bankruptcy. Chapters 7 and 11 of Bankruptcy Code give low priority to enviro obligations relative to the company’s creditors.

Companies are following the cues given by the system. It would be bad business to fully internalize costs, such as well capping, when a company is incentivized to neglect their environmental obligations and shift the cost to the public.

As disturbing as these stories are, they are not an anomaly in Indian Country. Colonization continues to produce messy outcomes, where uncovering harm and assigning blame gets lost as communities fight to survive. The Osage Nation does not intend to stop oil and gas production. As the Minerals Council continues working to increase headright payments, the Council and the Tribal government are simultaneously capping orphan wells across the reservation.

For many outside Indian Country, this may come as a surprise. The “ecological Indian” stereotype persists. It enables outsiders to preference their own ideas about how Native people interact with the land. I discussed this issue with Indigenous journalist Allison Herrera, who reminds us that “Native people are not a monolith.” She described how outsiders are quick to criticize her Tribe’s use controlled burning in the hills of California, when such practices are proven to prevent destructive wildfires.

“War on the Plains,” a painting George Catlin of an Osage warrior and a Comanche Lancer, from Wikimedia Commons

“And then there’s the way that Native people view themselves,” Herrera remarked. “And I think that sometimes those things are at odds and sometimes things, those things are not.”

As an Osage and future headright holder, I don’t feel comfortable with our continued dependence on oil. Common sense demands we look elsewhere for revenue, away from this finite resource. Solidarity with other colonized peoples demands that we stop contributing to climate change. It will ruin the food systems and homelands of the most vulnerable.

At the same time, the Tribe’s continued oil and gas extraction cannot be attributed to greed or apathy. Nor is it productive to paint us as victims of corporate capture. Instead, the forces of colonization that moved us westward, plundered our lands, and denied us equal opportunity are to blame.

And who, exactly, continues to push these colonial interests today? The large oil and gas companies implicated in these anecdotes are not the only bad-faith characters. Ask any Osage and they’ll tell you that the theft, malfeasance, and pollution was only possible because of the BIA.

A 1909 hand-drawn map showing Osage allotments found on Wikimedia Commons.

For background, all Tribes exist at the allowance of Congress, which holds plenary power over Indian affairs pursuant to Article I, § 8 of the Constitution. And nearly all North American Tribes suffered a form of violent removal from their homelands at the hands of European powers. Today, the Osage “appear to be the only tribe in the country whose form of government is dictated by federal statute.” “The Osage government and this trust is the single most… colonized Tribal nation in the United States,” claims Pipestem.

The primacy of the federal government over everything we do makes it difficult to protect against predatory corporations. In the oil and gas context, the Tribe can approve a lease. But once signed it is essentially beyond our control and in the hands of the BIA. The Tribe becomes “passive lessors of land.” “We’re the best custodians there are,” says Waller. “Yet, we’re still denied the driver’s seat on decisions pertaining to our land.”

For Tribes dealing with outside players, the feds will always garner more suspicion. History teaches this. When the federal government continuously fails to protect Tribes in accordance with the Trust responsibility, who can you trust? As a result, private or corporate actors seem trustworthy in comparison, or at least more predictable.

“We’re the best custodians there are,” says Waller. “Yet, we’re still denied the driver’s seat on decisions pertaining to our land.”

Ultimately, there is a risk that calls for increased regulation from outsiders will do more harm than good. By acting unilaterally without input by both the Minerals Council and the Tribal government, the BIA will repeat the colonialist gameplan of its past. When the Osage Nation enters its next chapter and transitions away from oil, it must work with the BIA. The onus falls on the agency to rebuild the Tribe’s trust and work as a partner.

The Osage people pass down stories about our ancestors who bought our reservation from the Cherokee Nation in 1872. The Tribe remained in Kansas as a group of men went South to survey the land. One of the men, Wah-Ti-Anka, was described as a prophet by Pipestem’s father. When he returned, Wah-Ti-Anka proclaimed that something was within the land. Something that would keep their children and elders from starving.

Many Osages believe that “something” was oil. Instead, Pipestem believes his father’s theory. The mystery resource wasn’t oil, but the sovereignty of the Osage nation. “These resources are not forever, whereas sovereignty arguably is.”