Traditionally, ‘dark money’ refers to election-related spending by groups not required to disclose their donors. The classic example of a dark money organization is a 501(c)(4) “social welfare” nonprofit. Also known as issue advocacy organizations, 501(c)(4)s can spend money on elections as long as that isn’t their primary purpose and they comport with Federal Election Commission (FEC) disclosure requirements. Since nonprofit organizations do not have to disclose funding information out of respect for donors’ privacy and freedom of association, their political contributions are ultimately untraceable back to the original donor. This has led to a massive influx of over $2.8 billion in dark money in elections.

Dark money usually only refers to election-related spend, but that is just one tributary of the funding streaming in and out of these entities—in fact, it’s the one with the most transparency, as the FEC makes information on these election expenditures public. 501(c)(4)s can spend unlimited amounts on political activities like lobbying, outreach campaigns, or advocating to lawmakers without any disclosure.

A 501(c)(4) is often affiliated with a sister 501(c)(3)—a “charitable” nonprofit—when it performs these political activities. The two nonprofits are technically registered as separate legal structures. But Ian Vandewalker, senior counsel at the Brennan Center for Justice, cautions against putting too much stock in this arbitrary division. “In reality, there’s [often] no distinction whatsoever. Different bank accounts, different tax IDs, but…if you think of a group as the human beings who comprise it, there’s no difference.”

The Honest Elections Project, a 501(c)(3), has the same executive director, address, and several of the same principal officers as Honest Elections Project Action (HEP Action), its 501(c)(4) arm. As HEP launches inflammatory ad campaigns about voting fraud and writes model legislation for states, HEP Action focuses on lobbying those state lawmakers and supporting the restrictive policies as they move through the enactment process. Despite actively influencing our democracy, these are not election-related expenditures that trigger FEC disclosures. And since they’re both 501(c) nonprofits, donations to them remain secret, whether it’s one dollar or one billion.

This protection of wealthy donors’ identity enabled Barre Seid, an incredibly private business tycoon that has been secretly funding right-wing agendas for decades, to make an earthshattering $1.6 billion donation to a conservative dark money network with complete anonymity. Seid donated his entire company to the Marble Freedom Trust, a 501(c)(4) organization overseen by Leonard Leo, the architect of the conservative Supreme Court who’s recently set his sights on pushing a right-wing agenda “in other areas of American cultural, policy, and political life.” Among Leo’s initiatives to impose a conservative agenda on the American people? The Honest Elections Project.

Justin Elliott, a reporter at ProPublica, was one of the first to break the story about Seid’s landmark donation, but he couldn’t have done it with only publicly available information. “It’s nearly impossible to know how 501(c)(4)s get money” unless they voluntarily disclose their donors, affirms Elliott. To verify the non-public information on this story, he had to spend months seeking out corroborating documents, faxing state offices to request incorporation records, and scouring all available information to find the ties between Leo and Seid.

But there’s still more to uncover. “If you want to hide where the money is going within these organizations, it’s pretty easy and totally legal,” Elliott adds. Donors can route their contributions through shell companies, other nonprofits, or donor-advised funds (DAFs).

Donations to DAFs appear as a general grant to a charity; at the fund, your donation is held and invested until you direct them to mete out contributions to certain causes. Some funds are known for their ideological bent—Donors Trust, for example, is widely known as the right-wing’s dark money ATM. But the largest DAFs are affiliated with major financial institutions, like the Schwab Charitable Fund, which handles tens of billions in donations and grants.

By routing this money through Schwab Charitable Fund, Leo and Seid further obscured their impact from the public eye. While donors have individual accounts and direct their own donations, a DAF outwardly appears as a single pool of funds—once the money goes in, it’s practically impossible to trace it back to the original donor.

Leo’s Marble Freedom Trust has granted over $320 million to the Schwab Charitable Fund since receiving Seid’s donation. In that same time period, Bloomberg and other news organizations have traced nearly $310 million from the Schwab Charitable Fund—a shockingly similar amount—to one of Leo’s well-known dark money funds, the very one responsible for the Honest Elections Project.

By routing this money through Schwab Charitable Fund, Leo and Seid further obscured their impact from the public eye. While donors have individual accounts and direct their own donations, a DAF outwardly appears as a single pool of funds—once the money goes in, it’s practically impossible to trace it back to the original donor. In its reporting, Bloomberg had to caveat that the released filings alone do not prove that the Marble Freedom Trust’s donation and Schwab Charitable Fund’s subsequent grant are related. Even after scouring records to identify the original donor and combing through thousands of pages of tax filings to find this flow of money, it’s still not possible to fully unmask this complex operation as the agenda of a few wealthy and well-connected individuals.

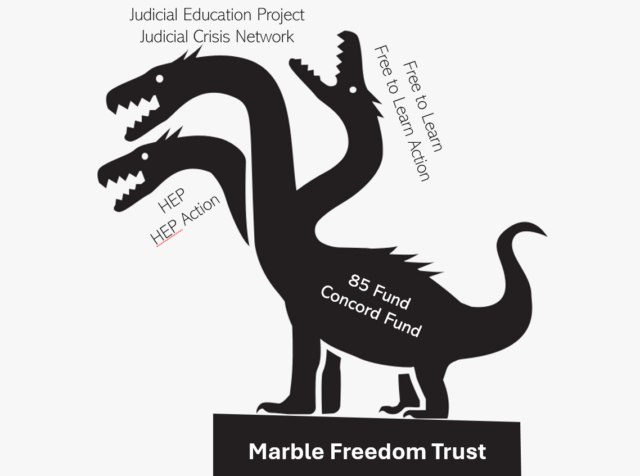

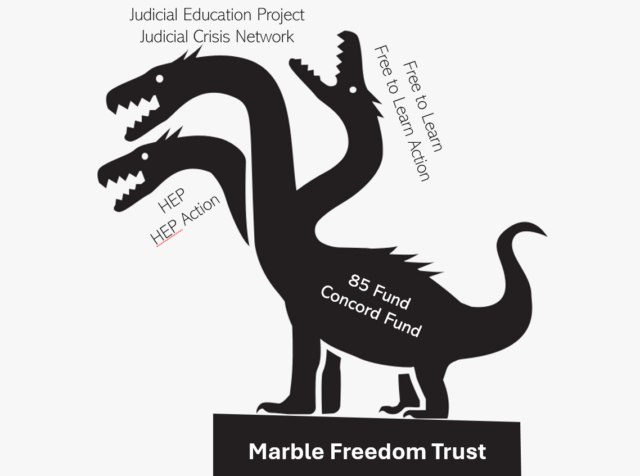

The corporate hydra: how a single entity masquerades as multiple identities

The Honest Elections Project doesn’t technically exist. Neither does the Judicial Education Project, Leo’s 501(c)(3) nonprofit that is devoted to stacking the courts with conservative judges. And the same is true of another organization affiliated with Leo, Free to Learn, which advocates to ban discussions of “political” topics like racism in schools. They’re all legal fictions.

To be more exact, they are fictitious names: artificial names deliberately adopted by an organization with a different legal name. In 2020, a nonprofit named the 85 Fund registered for three such aliases: the Honest Elections Project, Free to Learn, and the Judicial Education Project. And their sister 501(c)(4)s—Honest Elections Project Action, Judicial Crisis Network, and Free to Learn Action—are all fictitious names of the 501(c)(4) legally known as the Concord Fund. And as alluded to above, both the 85 Fund and the Concord Fund appear to be primarily financed by the Marble Freedom Trust.

Just write down the name of your choosing and voila, the hydra sprouts another head.

To be clear, these aliases aren’t subsidiaries, shell corporations, or some other, more complicated trick. As illusions go, it’s rather straightforward: organizations that want additional identities can simply ask for them. If you’re located in Virginia, as the 85 Fund and the Concord Fund are, all it takes is a two-page form and ten dollars. Just write down the name of your choosing and voila, the hydra sprouts another head.

Dark money nonprofits use this legal fiction to outwardly appear as an army of different organizations, despite in reality being no more than different limbs of the same creature. These aliases hide the fact that the same organization that worked to pack the Supreme Court bench with conservative justices (justices that Leonard Leo had an active hand in picking, no less) as the Judicial Crisis Network and Judicial Education Project also advocated to those very same justices in a bid for election subversion as the Honest Elections Project.

Graphic created by Varsha Midha.

Multiple news outlets have written about the 85 Fund and the Concord Fund. It was even the subject of multiple of Senator Whitehouse’s speeches on the corporate capture of our courts system. And yet, these false heads continue to deny their connection to the whole.

In a recent C-SPAN interview, Jason Snead, executive director of the Honest Elections Project, was asked point blank by a call-in listener about his organization’s connections to the efforts to push conservative Supreme Court Justices to the bench, and he avoided the question altogether. When pressed by the interviewer about whether HEP “gets involved in Supreme Court justices,” Snead denied it, saying “No, we don’t do anything along those lines,” treating the Judicial Education Project and Judicial Crisis Network as completely separate entities, rather than different heads of the same hydra.

There are no limits on how many times an entity can perform this trick. These funds also registered as the Alliance for Consumers and the Alliance for Consumers Action Fund, tackling Leonard Leo’s vendetta against consumer protections. And in March of this year, they registered as the American Parents Coalition and American Parents Coalition Action. This newest false head seems poised to target transgender youth and access to online content under the guise of “parental rights.” As these billionaires change their focus or expand their influence, their dark money organizations can keep sprouting new faces to further their agenda.

False handcuffs: are there any real guardrails on dark money’s influence?

Despite its influence on our political system, the vast majority of the 85 Fund and Concord Fund’s spending is not subject to much regulation since it’s not explicitly electoral. Similar to the Koch brothers, Leonard Leo’s dark money network merges different forms of political spending—be it campaign finance, lobbying, or more traditional nonprofit activities—in the aim of realizing an ideological vision broader than certain House or Senate seats. Harvard Law professor Nicholas Stephanopoulos noticed this trend in the Koch network several years ago: “These massive spenders in regular American elections are also using this other tool that is not regulated the same way, but…it’s serving a lot of the same functions as a conventional campaign finance.”

Stephanopoulos coined the term “quasi-campaign finance” to describe spending by dark money organizations on direct outreach to voters to push their policy agendas, and he believes that it should be regulated. The Judicial Crisis Network’s ad campaigns about judicial nominees and the Honest Elections Project’s amplification of conspiracy theories about mail-in voting to sway impressionable citizens would both qualify as quasi-campaign finance. Even though the Judicial Crisis Network ads were explicitly intended to hurt Senate Democrats up for reelection, they weren’t aired close enough to an election cycle to trigger campaign finance regulations. And while HEP’s outreach campaign may have influenced voting, it was not electioneering for a certain candidate.

Quasi-campaign finance appears completely unregulated in comparison to traditional campaign finance. Despite the lack of transparency about donors, nonprofits’ engagement in campaign finance is subject to disclosure requirements, bans against coordination, and a slew of other regulations. But upon closer inspection, the regulations that bind 501(c)(4)’s election-related spending start to resemble a magician’s handcuffs—they appear to be an ironclad constraint, only for the subject to escape them with ease. Even in the most regulated area of money in politics, our system struggles to enforce meaningful limits on dark money organizations.

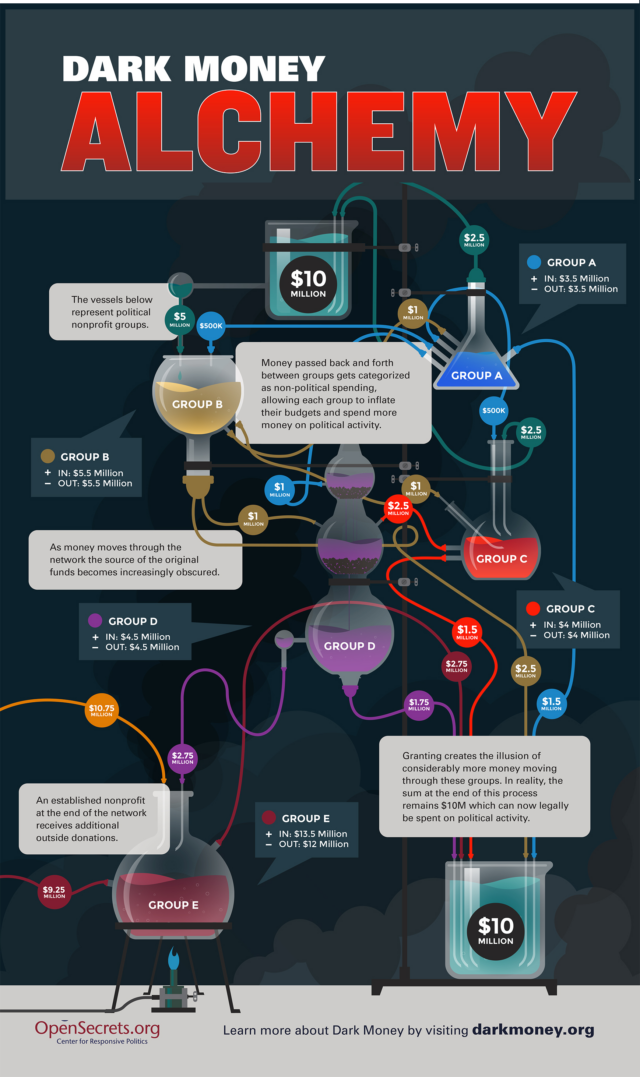

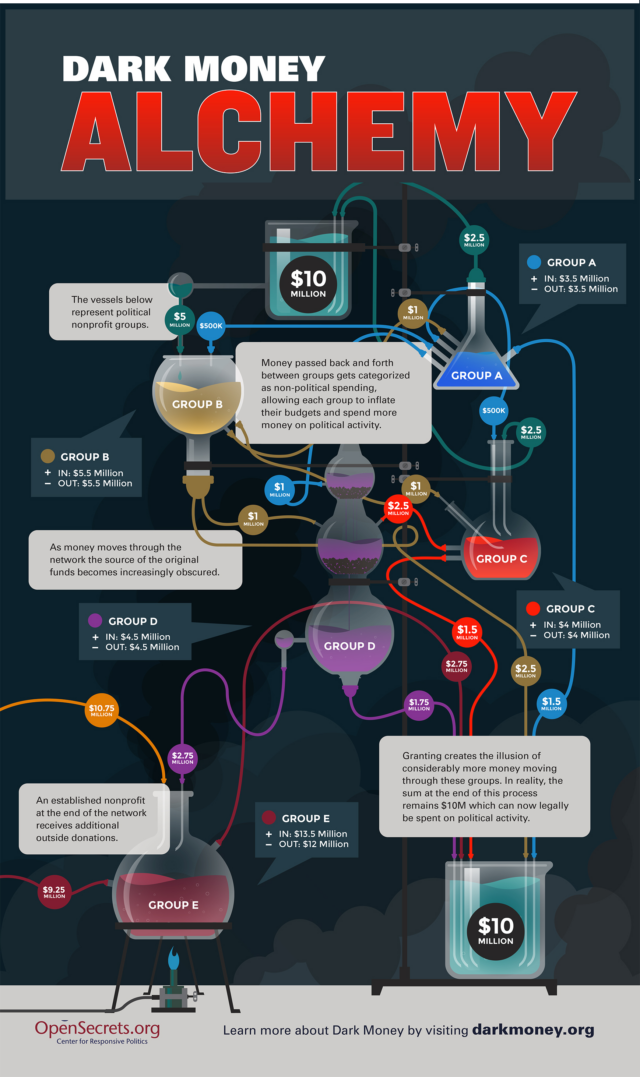

Let’s start with the basics: under the tax code, a 501(c)(4)’s primary purpose must be social welfare. What does that mean? Matthew Sanderson, an expert in tax-exempt organizations, explains that “technically, 50.1% of the money that goes out the door has to be for social welfare activities.” A common way to evade this already-lax requirement is through “churn,” when organizations launder money through their nonprofit network.

But upon closer inspection, the regulations that bind 501(c)(4)’s election-related spending start to resemble a magician’s handcuffs—they appear to be an ironclad constraint, only for the subject to escape them with ease. Even in the most regulated area of money in politics, our system struggles to enforce meaningful limits on dark money organizations.

Sanderson offers a quick example: imagine two 501(c)(4)s, Organizations A and B. Organization A makes a “social welfare” grant to Organization B, and then Organization B gives a grant of that same amount back to Organization A. This circular grant “hasn’t really diminished the overall money and capital… in play. But…during the tax year, it’s still on the right side of that spending calculation” for both organizations.

Churn in real life is rarely so straightforward. OpenSecrets has illustrated a more realistic example that follows how a single, hypothetical ten-million-dollar donation to a social welfare organization can transform through a maze of nonprofits into ten million dollars ready for electoral spend.

Image courtesy of OpenSecrets

The original donation is split between three nonprofits (Groups A, B, C), which then all pass different grants of the same money between them. They also issue grants to another organization in their network, Group D. This complicated shell game of “social welfare grants” racks up enough phantom spending on issue advocacy for the original three groups to spend all of the revenue they actually end up with on election-related activity. Group D diverts nearly half to election-related spending, in line with the “primary purpose” rule. Then, Group D can grant the remaining funds from the original donation to another organization, often an established nonprofit that’s ideologically aligned with the rest of the network. As long as the established nonprofit has some outside funds, it can easily complete the loop and spend Group D’s social welfare grant on electoral advocacy. Just like that, $10 million for “social welfare” transforms into $10 million ready to spend on elections.

Agencies like the FEC and the IRS can technically step in and prevent 501(c)(4)s from abusing the system like this. But they rarely do.

Shanna Ports, senior legal counsel at the Campaign Legal Center, has extensive experience filing complaints with the FEC about campaign finance violations. But since the FEC is a politically balanced commission, bipartisan consensus is required to move forward with any complaints. “The FEC often can’t muster that, which means the law goes unenforced,” Ports explains. “The Campaign Legal Center will take advantage of provisions…that allow you to sue the FEC if they dismiss your complaint. So when the FEC fails to enforce, we’ll go that extra step of going to court.” Ideally, that results in a court remanding the issue back to the agency with orders to deliberate and actually take action. But how long does this process take?

“Oh, many years. Usually, it takes the FEC years to make its first ruling on the complaint we file. If it’s something complex, or at all controversial, then the court proceedings can take years on top of that.” Ports is currently working on an FEC case about conduct that occurred in 2019, and is aware of similar cases that have been tied up in courts for nearly a decade.

As ineffective as the FEC is, the IRS appears to be even more toothless. Sanderson admits that this dark money churn “probably shouldn’t count [as] social welfare activities, but…the IRS has had its tail between its legs for basically the past fifteen years. It is unlikely to do anything about it.”

To begin with, the IRS has never been able to establish a standard for measuring acceptable levels of political activity for these organizations—the “50.1% rule” is just the de facto minimum that these organizations tend to abide by on legal advice.

The IRS has been flooded with thousands of complaints about 501(c)(4)s in the last decade, but the agency appears to have investigated almost none of them. It also continues to grant 501(c)(4) status to virtually every organization that applies. A constellation of factors has rendered the IRS powerless: the number 501(c)(4)s and related complaints have surged in recent years, the process to review 501(c)(4) status is intensely bureaucratic, and severe budget cuts hinder the IRS from pursuing more than its absolutely critical tasks.

Back in 2013, the IRS did attempt to investigate 501(c)(4)s whose primary purpose appeared to be political, flagging organizations with party names or other indicators of partisan bias. It resulted in some of the most severe backlash the organization had ever seen, leading to Commissioner Lois Lerner’s resignation as head of the IRS. Ever since, the IRS has seemed hesitant to audit or challenge any political nonprofit’s tax-exempt status.

The IRS does require nonprofits to disclose some aspects of their finances via Form 990 filings. But the content of these disclosures still fall far short of the level of information that voters would require in order to remain informed about the impact of dark money, and it’s not clear how trustworthy this reporting is. To no one’s surprise, the IRS rarely audits nonprofits—especially politically-involved 501(c)(4)s. In fact, the agency doesn’t even know who is funding them. It stopped requiring donor information from 501(c)(4)s in 2018.

Even in campaign finance, the most-regulated subset of dark money, enforcement mechanisms fail to meaningfully regulate 501(c)(4)s and the wealthy interests that are often hiding behind them. And outside of that conscribed realm, there’s an astonishing amount of latitude for organizations awash in secret funds to capture local elections, voting rights, climate policy, judicial independence, and so much more.

How do we reclaim the magic of democracy?

At every turn, the legal system seems to protect wealthy special interests’ ability to buy our political institutions at the expense of the average American’s right to a functioning democracy. The wealthy have the untrammeled right to pump money into our system in the name of free speech. Not only that, but they have the comfort of complete anonymity, as the courts continue to protect their right to freely associate with organizations.

And the tax code, for all its flaws, does one thing well: favor the rich. Barre Seid’s landmark $1.6 billion dollar donation was not just anonymous. It was completely tax-free. ProPublica estimates that, by donating his company to Leo’s tax-exempt organization, Seid evaded over $400 million in capital gains taxes, further amplifying the reach of his anonymous political donation. The Marble Freedom Trust can continue investing the assets from the company’s sale, creating a tax-free endowment for the conservative movement that will live on for generations.

The wealthy are able to exercise their unlimited resources in the name of “free speech,” and in doing so drown out the rest of Americans who don’t have millions of dollars to burn. And the rationale for donor privacy stems from NAACP v. Alabama, when the Supreme Court protected NAACP member lists from subpoena in the South during the 1950s. This protection was given in light of the real harm persecuted minorities faced in that context. It’s hard to argue that the same justification applies in equal measure to well-established billionaires or Fortune 500 companies. It’s even harder to argue that this right ought to outweigh voters’ First Amendment right to informed public discourse.

Dark money has become a driving force of our democratic system without ever showing us who’s behind the wheel.

Even the notoriously conservative Justice Antonin Scalia thought that anonymity without real threat of harm boded ill for democracy: “I do not look forward to a society which, thanks to the Supreme Court, campaigns anonymously…hidden from public scrutiny and protected from the accountability of criticism. This does not resemble the Home of the Brave.”

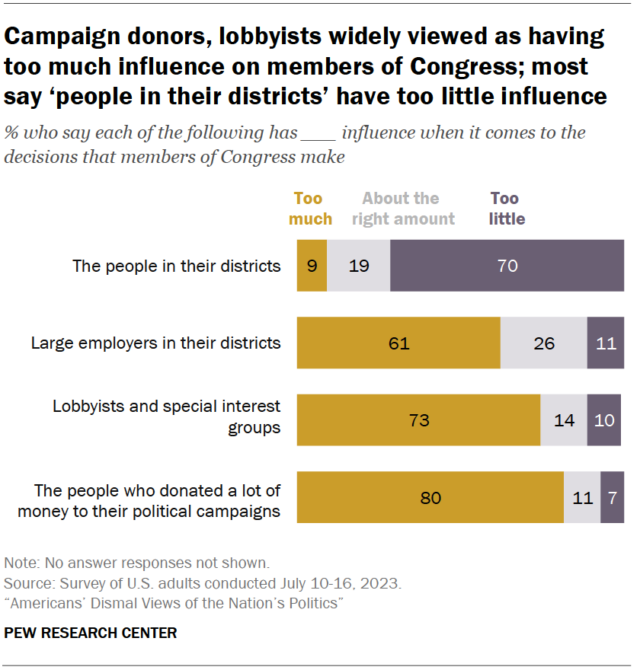

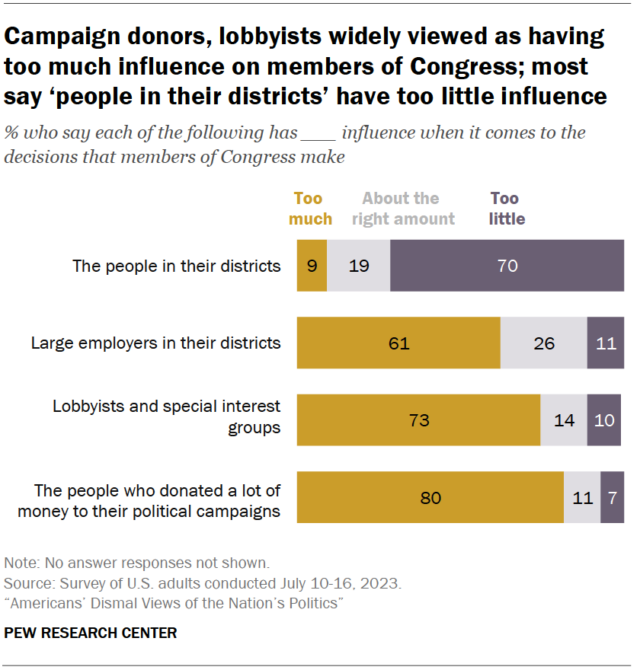

Voters have no way to even know which aspects of our democratic institutions, elections, or policies are shaped by forces of dark money. We have no easy way to discern whether the messaging we’re receiving about a local ballot initiative or a national hot-button issue is due to grassroots organizing or dark money astroturfing. We don’t have all the information to accurately judge whether legislators are responding to the concerns of their constituents or the money they see behind special interests. We also can’t tell how far these special interests reach—as Leonard Leo’s network shows, the money behind one issue, like voter suppression, can be just a single aspect of a multi-pronged attack on our democratic system. And research shows that these background influences can subconsciously play a large role in voters’ choices, even if we believe that our votes solely reflect our own interests and priorities.

“I do not look forward to a society which, thanks to the Supreme Court, campaigns anonymously…hidden from public scrutiny and protected from the accountability of criticism. This does not resemble the Home of the Brave.”

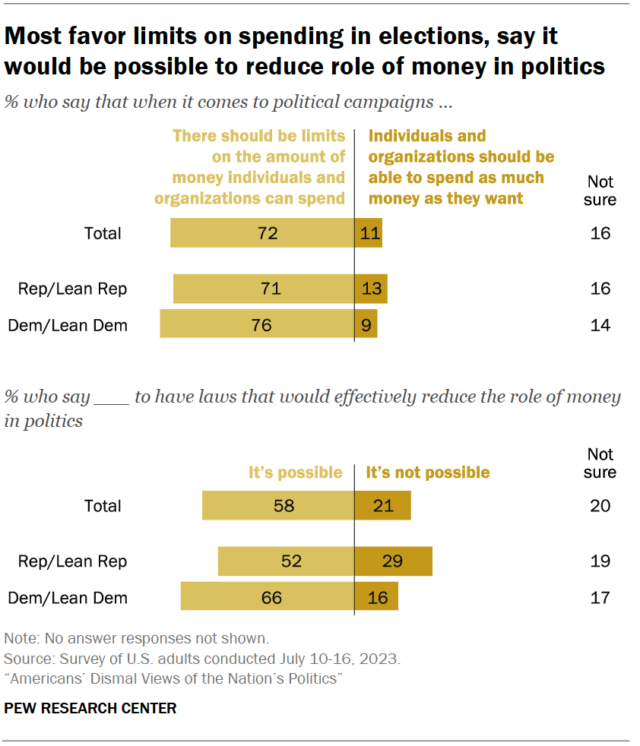

A democracy is meant to be governed by the will of the people, exercised through the active and informed use of the vote. Wealthy special interests have embedded themselves in our political system, secretly distorting public discourse and governmental institutions in their favor. Dark money has become a driving force of our democratic system without ever showing us who’s behind the wheel. And the American people are catching on—a vast majority already recognize that wealthy special interests exert too much influence on our government, while actual voters don’t have enough impact

Image courtesy of Pew Research Center

Shining a light on the extent of dark money’s influence would definitely help hold these forces accountable. Senator Whitehouse, who has been sounding the alarm about dark money since Citizens United, has reintroduced the DISCLOSE Act. Among many transparency provisions, the DISCLOSE Act would require that 501(c)(4)s engaging in political spending disclose their major donors in election cycles, funders of judicial advocacy reveal themselves, and organizations name their top funders when airing political ads.

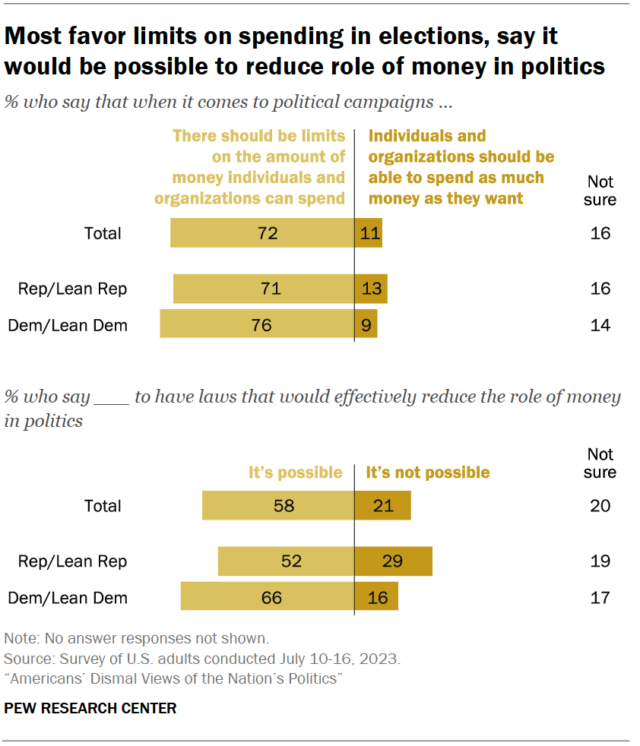

But that doesn’t meaningfully reduce the wealthy’s control of our institutions; it just gives us a glimpse at who’s in the driver’s seat. We need to determine the role that money should play in our political system in order to effectively reckon with the power it currently wields. A majority of Americans agree that we can and should create meaningful limits on the role of money in politics—it’s a top policy priority among voters for 2024.

Image courtesy of Pew Research Center.

In this current landscape, broader reform may seem impossible. Agencies are already ineffective at enforcing existing regulations on dark money. Even as both Democrats and Republicans rail against the wealthy’s undue influence on our government, both sides rely heavily on dark money in their campaigns. And the courts—the same courts that have been shaped by these dark money influences—continue to bolster the wealthy’s safeguards for unlimited, anonymous spending. It seems like our current government and legal structure simply isn’t equipped to regulate this activity.

But that doesn’t mean we ought to accept the buying and selling of our democracy, let alone see it as a legitimate aspect of our political system. This is an active attack on our institutions—coordinated dark money networks like Leonard Leo’s are attempting to erode the democratic check that the people provide as he enacts his ideological vision through the conservative courts.

Our government is meant to be by and for the people, not just those who can afford the price of entry. Fred Wertheimer, a leading activist on regulating money in politics, once said: “There is nothing in our constitutional democracy that accepts that…the richest people in the world can control our destiny.” It is time to envision broader, bolder reform for money in politics that empowers the average American voter, creates an environment of informed public discourse, and aligns the functioning of our system with the stated ideals of a representative democracy.