The physical construction of the primary school is solid, but its legal foundation is shaky. As students were drawing self-portraits and writing their ABCs during the first weeks of classes, the Kisan Village Council received notice that they were being sued by Regavim, an Israeli organization dedicated to advancing the right-wing settler movement in occupied Palestine.

The Kisan School

Credit: Lea Kayali

Regavim’s lawsuit against Kisan alleges that the construction of the school is illegal, that it should be demolished, and that the Israeli government hasn’t done enough to see to its destruction. The non-profit claims that these classrooms are an illicit land grab by Palestinians, even though they are built on land that the people of Kisan have lived on for centuries. The case against Kisan is part of Regavim’s strategy to use the courts to conquer the land around Gush Etzion settlement bloc – one of the largest settlements in the West Bank – ultimately expanding Israeli control over the region.

Tracing Regavim’s funding would take one across the Atlantic Ocean and to the sequined streets of the Garment District in New York City. The Central Israel Fund (CFI), one of Regavim’s major donors, is headquartered there. CFI is a non-profit corporation that uses the American tax system to subsidize efforts like the lawsuit to destroy the Kisan school.

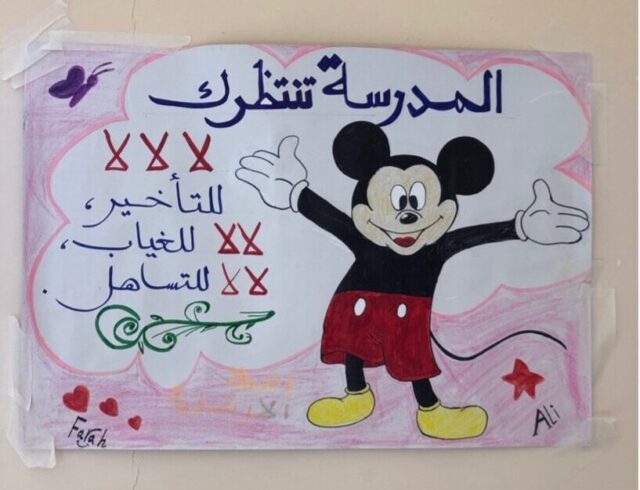

A student’s drawing that reads “school is waiting for you” and lists the school’s policies.

Credit: Lea Kayali

This invisible paper trail has not gone unnoticed. Several grassroots groups in Palestine have been raising alarms about Regavim and CFI’s shady practices for years now. These activists have coalesced under the Defund Racism campaign, and their plan is to dry up the well of funding that sustains Regavim’s harassment and dispossession of Palestinian communities.

The Kisan school has become one of the battlegrounds for the future of Palestine.

__________

Regavim’s lawfare aligns with their fervent commitment to the total colonization of Palestine. The organization proclaims itself “a social movement established to promote a Zionist agenda for the State of Israel.” Over the greater part of the last century, Zionist forces have made millions of Palestinian refugees, have murdered thousands of Palestinian people, and have erased hundreds of Palestinian villages off the map.

Kisan is one of dozens of remaining communities that are targeted as part of Regavim’s mission to accelerate the settler movement. Regavim’s flagship campaign, for example, advocates for the demolition of the entire village of Khan al Ahmar to make way for the expanding of Ma’ale Adumim – a settlement established in 1991. The attack on Khan al Ahmar began with the 2018 destruction of the local school. Four years later, the charity has progressed to petitioning the court for the whole sale erasure of the village. Throughout this process, Regavim inverts reality with aggressive messaging that alleges Palestinians to be foreigners on their own land.

The settler movement playbook is effective, and it starts with occupying Palestinian land.

The settler movement playbook is effective, and it starts with occupying Palestinian land. Initial Zionist settlement is predicated on erasure of whole communities – like the Jahalin Bedouin tribe that used to live where Ma’ale Adumim now sits. Settlers then target the towns in the surrounding area and pick off critical infrastructure like schools. This forces families to make the heartbreaking choice of whether to stay in their ancestral homes or search for a better future for their children. Eventually, settlers persist against the remaining villages like Khan al Ahmar to demolish the entire community.

Qanoob, a Bedouin village near Kisan, facing erasure and continued settler violence.

Credit: Tala Alfoqaha

Zionist settlements in the West Bank are illegal according to international law and ostensibly condemned according to US foreign policy. Yet they continue to crop up at a break-neck pace. The Israeli government subsidizes these settlements heavily. Settlers can move directly to Ma’ale Adumim or Gush Etzion from New York or Vancouver or London. They’re rewarded with a bundle of government aid such as all-expenses-paid travel, Hebrew instruction, a year of free rent and discounted education, low-interest mortgages, and more. Regavim supplements this process by providing myriad services to Zionist settlers, including legal advocacy. The NGO is critical to entrenching and growing the 600,000-person settler population in the West Bank.

Regavim’s usual business is dispossession – targeting Palestinian homes and un-housing the families within them. However, the non-profit also promotes government lobbying and paramilitary activity. Regavim CEO Meir Deutsch boasts that during the increased violence in May of 2021 he set up a “civilian war room” and mobilized West Bank settlers to flood cities like Lydd that have a mixed Palestinian and settler populations. A bus full of these armed vigilantes participated in lynch mobs and the murder of Mousa Hassuna – a 31 year old father of three who is remembered by his wife Marwa as “the love of [her] life.”

Regavim’s endorsement of racial violence spawns directly from the foundational ethnic cleansing, which Palestinians call the Nakba, or catastrophe. The Nakba continued in the form of the Naksa – the occupation of the rest of Palestine in 1967 – and the incremental genocide committed in the form of bombing raids on Gaza. The slow draining of Palestine’s lifeblood is facilitated by the US government, which both normalizes the last 74 years of occupation in Palestine and arms the beast of Israeli colonialism in the form of an annual $3.8 billion in military steroids.

Israeli settlers occupying a Palestinian home and garden in Sheikh Jarrah, East Jerusalem. Credit: Tala Alfoqaha

Ongoing dispossession can be felt in every corner of historic Palestine, but the new frontier for Zionists is the settlement movement in East Jerusalem and the West Bank. After the Oslo Accords of the 1990s, the West Bank was diced up into three zones: Areas A, B, and C. The Palestinian Authority became the subcontractor of the occupation in Areas A and B. The Israeli military maintains total control of Area C, which compromises some 60% of the West Bank. This arrangement, which was meant to be a temporary transition to Palestinian statehood, is now the permanent state of affairs. Military occupation has become quotidian. The call to prayer floats through jail windows to land on political prisoners’ ears. Mothers lie photos and prayer beads on the beds of their murdered children. Families dip pita bread into olive oil and za’atar on the ruins of their demolished homes. Colonization percolates through every aspect of Palestinian life.

__________

Kisan, like most rural Palestinian communities in the West Bank, is part of Area C. The 600 villagers are surrounded by several settlements, including Gush Etzion, with a population of 80,000. Community members in Kisan are frequently subjected to unpredictable Israeli settler incursions. Some Kisan villagers say they live in fear of attacks, which range from property damage, to brutalization, to murders, and have increased dramatically since 2020. On April 26, Raja Barakat, an elder farmer from the village, was rushed to the hospital in his blood-soaked shirt after being beaten by settlers with sticks and doused in pepper spray. As the settler population steadily encroaches on Palestinian towns, the violence intensifies.

Kisan’s old school, a small, windowless caravan, was located close to a settler-only thoroughfare. In the year before the new school was built, seven children were run over by settlers on their way to class. “It’s scary walking to school and back as there are always problems,” one pupil, Muhammad Ata Abiat, told Al Jazeera. The volatile situation led to high dropout rates for students, especially girls.

Kisan village leaders expect that the new school will help keep children safe. “Today, things are easier in the village.” Ahmad Ghazal, a resident of Kisan, explains. “[The new school] has relieved their suffering… and strengthened the steadfastness of the people of the village.”

“[The new school] has relieved their suffering… and strengthened the steadfastness of the people of the village.”

There’s just one problem. In Area C, Palestinians are forbidden by their occupiers from building on their own land. The bureaucracy of this oppression is maintained through a rigid permit system – where Palestinians are denied 98% of their requests. Without a permit, Palestinian buildings are vulnerable to demolition. In the last two years alone, 2,065 Palestinian structures have been destroyed by the Israeli army. Four of those recent demolition orders have been issued in Kisan. “They are still trying to destroy [the village],” Ghazal explains. Over the years, Israel has expropriated dozens of acres of Kisan’s land.

Regavim frequently uses the deny-and-demolish permit system to pressure the Israeli government to issue court orders against Palestinian constructions. With its operating budget of over 4.5 million Israeli Shekels (1.33 million USD), Regavim maintains high-tech surveillance equipment, including drones. According to eyewitness testimony, the drones frequently hover around the community and photograph people inside their houses through the windows. If a Palestinian succeeds in knocking down a Regavim drone, the Israeli military invades their village to get it back. In Kisan, Regavim knows about every marriage, all the children born to the community, and each new home built. They surveil the most intimate moments of Palestinian life. This evidence of Palestinian activity allows Regavim to file claims with the Israeli government. Often, they employ this information to get stop-work orders issued before structures are even built.

Regavim’s aerial footage of the Kisan school during its construction.

Credit: Lea Kayali screengrabbing from Regavim’s English twitter account

Regavim uses this surveillance as a weapon in their lawfare against the Kisan School, but the suit is just the latest in a multi-year battle between Regavim and the people of Kisan. In September of 2020, Regavim took to twitter, lamenting the building of the school, and attached aerial footage that their drone captured. They petitioned the Israeli court to quash the building, and were dismissed because the government had already issued demolition orders against the school. Perhaps because of the Swiss Agency’s involvement, or perhaps out of bureaucratic shortcomings, the demolition was never carried out. When the school finally opened for classes, Regavim returned to the Israeli court, suing Kisan, but also the Israeli ministry of defense and the local settlement council.

The bizarre combination of players in the suit is illuminating of just how extreme Regavim’s mission is. Not only are they suing the Palestinians whose land they plan to usurp, but they’re also suing the colonial government and occupying military for not fulfilling their request fast enough. The relationship between right-wing settlers and the state is usually reversed. More often than not, cavalier settlers who occupy Palestinian land in rogue “outposts” are eventually absorbed into the settlement apparatus of the state. That the Israeli government and Regavim are on opposite sides of a legal battle is especially ironic given that Regavim receives millions of Israeli shekels in state funding.

Demolishing the Kisan school is of strategic importance to Regavim. The organization’s attack is part of a larger plan of theirs to target Palestinian education in Area C. Last year, Regavim released a “situation report” on seventeen Palestinian schools – including Kisan’s – claiming that the schools are part of a malicious plot of “dense Arab settlement in Area C.” In the document, they identify an additional 100 schools as future targets. In Regavim’s view, these schools serve as reminders that Palestinian communities are investing in their future on their land – a threat to colonization.

In Regavim’s view, these schools serve as reminders that Palestinian communities are investing in their future on their land – a threat to colonization.

“Until today they are trying to choke out any education in the school,” Ghazzal laments.

__________

Despite this repression, Palestinian organizers are committed to resisting continued settlement on their land. Hundreds of Palestinian organizations, villages, and community leaders have coalesced against Regavim and the other settler organizations like it. Together, they have created the Defund Racism Campaign, to raise awareness about settler violence perpetuated by groups like Regavim, and to move funds away from these NGOs that perpetuate colonial violence. The Campaign aims to revoke the charitable status of Regavim’s American funders. “Charities should be organizations that promote human values. Regavim promotes war crimes,” explains Munir Nuseibah, the director the Community Action Center of Al-Quds University. Nuseibah’s center is one of over 200 organizations and 20+ Palestinian municipalities who have endorsed the campaign.

Perhaps one reason for the Campaign’s popularity is its unique approach: grounding international solidarity in Palestinian soil. Bana Zuluf is an organizer with the Defund Racism Campaign. She explains that she was drawn to the Campaign because of their focus on the material conditions of Palestinians on the front lines of dispossession. “We joined [together] in the interest of decolonization… in the interest of disrupting those systems, and abolishing those systems eventually.” For Zuluf, Regavim’s surveillance, lawsuits, and demolitions are “all about the land.” Resistance, she says, must be tailored accordingly: centered on returning Palestinian land to the Palestinian people, particularly in the communities facing the brunt of settler violence.

An integral part of this movement is building a coordinated strategy with the community members in targeted villages. “They’re part of the process.” Zuluf articulates. “They make decisions in the campaign.” Community partners have highlighted that Regavim is just one of several Israeli organizations who use these aggressive legal tactics to force Palestinians from their homes. Other similar non-profit corporations include Ateret Cohanim, Ir David, the Israel Land Fund, and The Hebron Fund. As the Campaign notes:

“Ateret Cohanim is running lawsuits against Palestinian families, leading to their eviction, such as the Rajabi Family, or the Abu Nab Family in Silwan. [Ir David] is not only part of the current eviction in Silwan, but also in the past took over houses, such as from the Abbasi Family in Silwan. The Israel land Fund initiated a lawsuit resulting in the self-demolition of the homes of the al Shawamreh and Abu Rumeineh families in Beit Hanina, the Hebron Fund supports a soldier rest area, indirectly supporting a foreign military.”

Crucially, these groups have more than a common goal. They have a common donor base: Americans. American non-profit corporations are writing the checks that are cashed to buy the drones that surveil families in their homes, the weapons that arm lynch mobs in Lydd, and the lawyers that file lawsuits to demolish Khan al-Ahmar and the Kisan school.

American non-profit corporations are writing the checks that are cashed to buy the drones that surveil families in their homes, the weapons that arm lynch mobs in Lydd, and the lawyers that file lawsuits to demolish Khan al-Ahmar and the Kisan school.

“It’s really important to think about these settler organizations in clear terms” states Mohammed Al-Kurd, a campaign spokesperson and a Palestinian activist from Sheikh Jarrah. “These are often organizations, entities, that are funded by billionaires, that operate under a charity guise… They are inherently a body of colonial violence, that behaves with such arrogance and impunity.”

Without American dollars, the activists argue, groups like Regavim wouldn’t be as successful, and the lawfare wrought upon villages like Kisan could be hamstrung. In 2019, up to 45% of Regavim’s donations came from international donors. Badee Dwaik, a human rights defender from Hebron, emphasizes that “this campaign is a very important movement – to stop this money from going to the settler organizations.”

Many of these American NGOs are headquartered in New York, so the Campaign’s principal goal is for NY Attorney General Letitia James to revoke the charitable status of these organizations. “There’s a lot of philanthropy money that’s coming in, allowing these systems to be.” Says Zuluf. Repealing these American corporations’ tax-exempt status could shut down the flow of capital from the US into Israeli settlements.

Campaign organizers have connected with Palestinian and Palestine-solidarity activists throughout the US to make this goal a reality. This year, organizers from the Palestinian Youth Movement, Within Our Lifetime, and Jewish Voice for Peace took to the streets to protest their local benefactors of the settler movement.