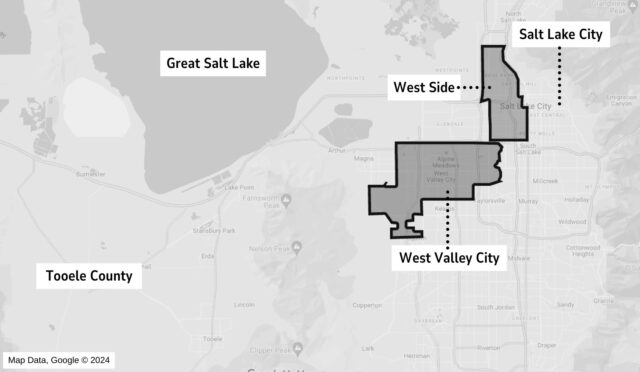

The West Side

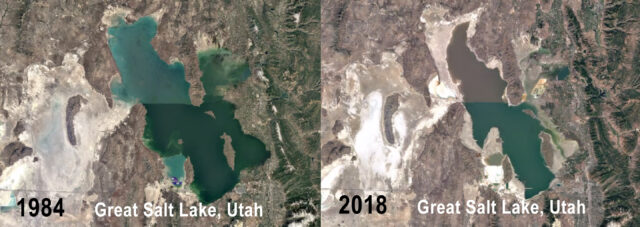

Given the severity of this crisis, the potential collapse of Great Salt Lake has been covered extensively, both nationally and internationally. But there’s perhaps no one paying closer attention to this problem than the communities living nearest to it: the West Side.

The West Side has historically been and is still home to Salt Lake’s diverse immigrant, minority, and low-income communities. Angela Lezaic, a college student and budding journalist, was born in Utah to working-class refugees from Serbia and has lived in West Valley her whole life, part of the greater West Side area. To Lezaic, the West Side, filled with people from different backgrounds, is much more than a geographic label. It’s “a place of comfort.”

But Lezaic is also intimately aware of the fraught history between the West Side and the greater Salt Lake City area. “The rest of the state doesn’t exactly respect or love this place the way that we do.”

That’s led to starkly different realities between the western and eastern portion of the city. As early as the late 1800s, city officials placed any “undesirable” activity—like factories, landfills, or trash incinerators—in the Westside, and the area continues to be left behind in a variety of ways.

There’s also an important caveat to the idea of procedural justice: there’s a difference between simple participation and effective, meaningful participation.

For example, the West Side sees much more pollution than the eastern portion of the city. At the local level, the West Side deals with more sources of pollution, including interstates, railroads, and an open pit mine visible from space. However, experts caution against fixating on any single source when assigning blame. For example, Dr. Daniel Mendoza, a Professor in Atmospheric Sciences at the University of Utah, notes that significant sources of pollution include Great Salt Lake, farms, industry, and even tire residue from personal vehicles.

The West Side is also disadvantaged at the regional level. Salt Lake City often struggles with what are known as wintertime “inversions” in which pollution and cold air accumulates within the Salt Lake valley, trapped by warmer air above. The West Side is lower in elevation, and as Lezaic notes, “if you’re on the east side and you live higher up on the mountains, you can literally look down and see the layer of smog that’s settled down on the valley.”

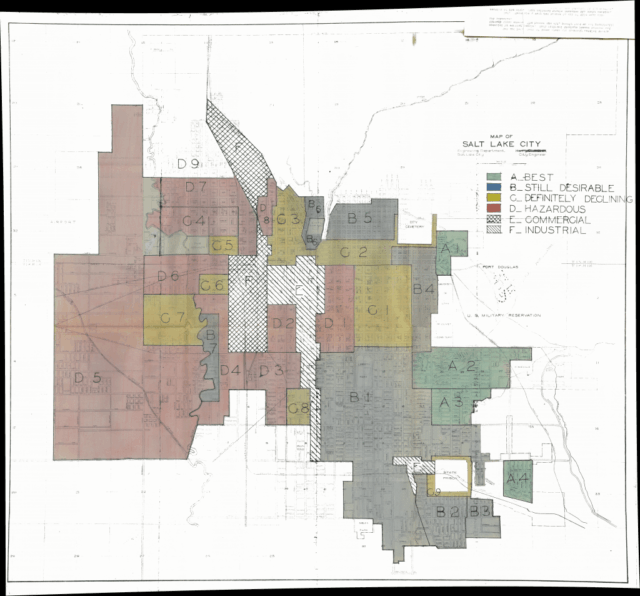

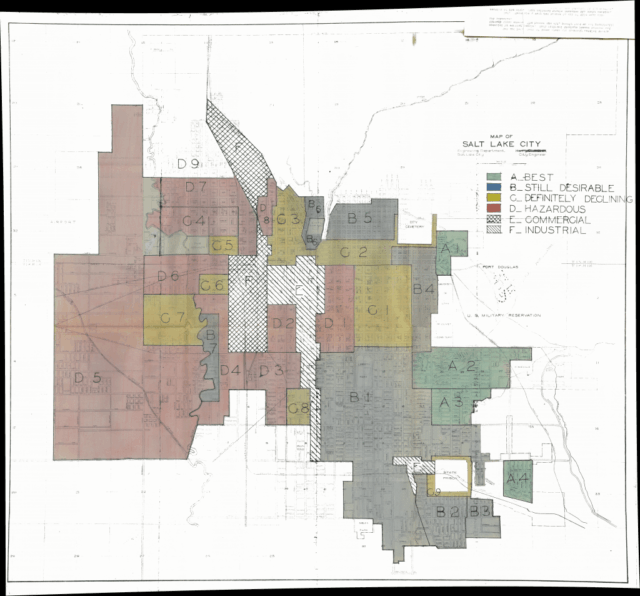

Beyond pollution, the physical landscapes of the eastern and western portions of the city differ greatly. Lezaic points out that while the east side benefits from brownstones, yoga studios, and old, grand trees dotting the landscape, the West Side sees much less: smaller, fewer trees, for example. In fact, the West Side has fewer amenities in general, including a relative lack of medical facilities, education institutions, and grocery stores—a consequence of redlining practices.

A georectified image of the redlining map of Salt Lake City. Courtesy of Mapping Inequality, https://dsl.richmond.edu/panorama/redlining.

This gap is top of mind for Lezaic, as a student who often travels between the areas. “To me, the West Side is sometimes depressing, not because of the wonderful people who live there and do their best to get by. But, because each day when I commute between the east and the West Side to get to school and to work, I’m just reminded that the people in power here have created this reality for my community . . . The people on the West Side deserve that same beauty and safety in their lives, too.”

To Lezaic, the culprit is clear. The government “created these cracks and then pushed the West Siders right through them.”

Lezaic is not alone in finding fault with the government. Other West Siders expressed similar frustrations, including Terry Marasco, who beyond being a West Side neighborhood council chair is also a Director for the Westside Coalition, an advocacy and community building organization.

“The West Side has been ignored by administration after administration,” Marasco states.

Procedural Justice, Just Without The Justice

Ultimately, the struggles of the West Side highlighted by Lezaic and Marasco showcase how easily state and local government decision-making processes can be co-opted by corporations, turning procedural justice into procedural injustice.

The concept of procedural justice speaks to the processes that officials use to make decisions, resolve disputes, and allocate resources. It has a long history and has been applied to a variety of settings, including criminal justice, environmental justice, and even employer-employee dynamics.

For corporations and the government, the veneer of a procedurally just decision-making process is important.

Procedurally-just processes aim to ensure the effective, meaningful participation of communities in important decisions, often through public hearings, public comment periods, or advisory boards. While opponents claim that procedural justice reforms create unnecessary, time-consuming, and expensive red-tape, if all goes as planned, decisions made using these processes will be better. They will also have more buy-in and legitimacy from communities because the process will have accounted for the perspectives of various stakeholders.

Achieving procedural justice, however, can be more complicated than it seems. Socioeconomic conditions can play a significant role in levels of engagement and access for different communities, including those in the West Side. For example, many people don’t always have the time or ability to attend multiple-hour long community council meetings, and there can be other barriers including language access and even immigration concerns.

There’s also an important caveat to the idea of procedural justice: there’s a difference between simple participation and effective, meaningful participation. Allowing the public to participate does not mean much if the public’s concerns don’t actually matter to officials.

Lezaic and Marasco both highlight this concern. “They say that they’re accounting for West Siders’ perspectives,” Lezaic notes. “They’ll let them come to council meetings and submit comments on the subject of the highway expansion, for example. But they really just do that to placate people and buy themselves more time to get away with these things.”

Lezaic continues: “Westsiders have already said their piece. They’ve expressed their dissent and their frustrations, and they’re just not being listened to.”

Marasco agrees, though he would even go as far as to say that officials do listen to West Siders—it just doesn’t matter. For example, he recounts that while at a public comment meeting, one government representative responded to his concerns by saying: “We will listen to you, but we don’t have to do anything that you’re suggesting.” For Marasco, “[t]hat is Utah . . . all over right down to the city council.”

“State Capitol of Utah 3” by Strobel Adventures is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

There is an insidious type of danger when procedural injustice masquerades as procedural justice. These insincere procedural measures can be actively harmful to affected communities, taking up their time and resources.

As Lezaic emphasizes, “the issue isn’t that people aren’t included in the conversation of their own destruction.” Rather, “they create conditions that make it difficult for West Siders to organize themselves and build community networks that are conducive to actual effective action.”

Lezaic states that “public officials and these businesses think that if they tire out these already tired communities, by wasting more of their time, they’ll get to just slide by and do whatever they want.”

And there lies the crux of it. When West Siders are raising their concerns to state and local officials about an issue, it’s not just them and the officials in the room. Corporations, ever-present third parties with a disproportionate amount of influence, are there as well.

For corporations and the government, the veneer of a procedurally just decision-making process is important. It adds legitimacy to unfair decisions, decisions which inevitably privilege one group—often corporate and industrial interests—at the expense of another. So, when people who are negatively affected by a decision voice their concerns, they are told that there is nothing anyone can do—after all, the decision adhered to the process.

The Corporate Capture of Great Salt Lake

Utahns have long raised concerns about corporate capture, a term which describes the untoward influence of corporations and money in the decision-making processes of government. While not a problem unique to Utah, corporate capture is widespread in the “Industry State,” with examples including lobbying by the powerful Board of Realtors, the billboard industry, or even Prepare 60, a group of water conservancy districts that has been accused of campaigning against conservation efforts.

“The rest of the state doesn’t exactly respect or love this place the way that we do.”

Beyond lobbying, money in politics represents another major concern. Statewide elections, though they see smaller donation figures than national elections, are not immune, especially given Utah has no donation limits. Utah’s State Senate, Assembly, and gubernatorial elections in 2024 have already received over $450,000 in donations from Energy and Natural Resource companies alone. In addition, as of 2022, 56 percent of the over $40 million in career campaign donations to Utah lawmakers came from special interest groups.

These donations seem to have real-world impact. Four days after donating $50,000 to Governor Cox’s campaign in 2023, U.S. Magnesium reached a settlement with the Utah Department of Environmental Quality for environmental violations, receiving a monetary penalty that some have called too lenient. The settlement stands in stark contrast with the fact that one federal study in 2023 found that the company was responsible for up to 25% of the smog in summer ozone and winter inversion events in the region.

Image of an eastern portion of Great Salt Lake and its evaporation ponds. Image courtesy of the Earth Science and Remote Sensing Unit, NASA Johnson Space Center.

Those on the West Side are no strangers to the reality of corporate capture, and they highlight the role of industry in controlling the priorities and decision-making of the state government, especially in relation to the Great Salt Lake crisis that disproportionately affects them.

One salient example includes a recent bill, signed into law by the Governor in March 2024, to prevent the legal recognition of personhood for lakes, forests, and other natural bodies; personhood status would provide some legal rights for the natural entities. The sponsor of the bill, State Representative Walt Brooks (R), explained that the bill was a response to lawyers, environmentalists, and other groups using personhood as a “weapon” to push forward their “agendas.”

“Frankly,” Marasco states, “the only reason that they’re concerned about the lake is . . . the commercial quality, not the fact that it’s poisoning us on the West Side.”

While there is an ongoing debate on the usefulness of personhood for natural entities like forests and lakes, the quick, reactionary state legislative response that preemptively blocked even the possibility is in clear tension with the fact that corporations, clearly non-human entities, have enjoyed legal personhood for years. And, while many think the personhood status of corporations is a given, it’s important to remember that corporate personhood is a legal fiction, established through the courts.

Terry Marasco brings up an additional example of the influence of corporations on Great Salt Lake, as he sees it. He argues the legislature’s attitude is “farm first, lake second.” “Yet,” he continues, “at the same time the rhetoric is: it’s a national asset, and it’s a Utah asset.”

Marasco further argues that even the lawmakers’ concerns about Great Salt Lake stem from industrial considerations relating to the mineral extraction, brine shrimp, and even ski resort industries—the dust from the lake blankets ski slopes and causes the snow to melt faster, shortening ski season. “Frankly,” Marasco states, “the only reason that they’re concerned about the lake is . . . the commercial quality, not the fact that it’s poisoning us on the West Side.”

As reported by Brooke Larsen, the Utah State Legislature has passed over 20 bills aimed at saving Great Salt Lake. For example, through SB 277 and SB 18, signed into law in 2023 and 2024, respectively, Utah lawmakers have worked to update water laws to allow instream flows to the lake to be considered a beneficial use, rather than a waste.

However, many environmental advocates argue that lawmakers have just paid lip service to conservation, with little actually being done to reduce water consumption and to save the lake. The state so far has refused to set a healthy water level, and concerns have been raised that the state cannot actually track if any of the water that is conserved through measures like SB 277 is actually getting to the lake, as opposed to just being used by others downstream.

In 2022, Governor Cox’s public lands office even asked federal regulators to approve a U.S. Magnesium proposal to dredge additional canals into the shoreline of Great Salt Lake to enable the company to gain access to more water. Only after a public outcry in December of that year did the office rescind its support.

As a more explicit example of corporate capture, take HB 453. Signed into law in 2024, the bill raises taxes for mineral companies while establishing additional regulations for the mineral extraction industry, which had historically been encouraged to use every single drop of the “waste” water that made it to the lake.

While on the surface it might seem to represent a shift in tone for how Utah deals with industry, the bill may not actually be as transformative as it seems. After some tense initial responses from industry, lawmakers cut language that required companies to return as much water as they use. The tax rates in the bill were also slashed and are now tied to voluntary agreements to use less water.

Both U.S. Magnesium and Compass Minerals eventually expressed support for HB 453, with Compass Minerals CEO Edward Dowling Jr. stating the company was appreciative of “the collaborative approach of the bill sponsors.” Utah Rivers Council, an environmental nonprofit, rated the bill a D+.

The state government is doing so little, according to its critics, that advocates have recently filed a petition to get Wilson’s phalarope, a tiny migratory bird, listed as “threatened” under the Endangered Species Act, specifically to ensure that the federal government starts having more of a say in decisions around the lake.

“Wilson’s Phalarope in Flight” by USFWS Mountain Prairie is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

The Inland Port

There is perhaps no better issue to illustrate the effects of corporate capture on both Great Salt Lake and the West Side than the Inland Port project. The Inland Port project, an economic development project originally conceived in 2016, is a collection of “dry ports”—inland import-export centers that interface extensively with train networks and trucking lines. For businesses, it represents a lucrative opportunity for profits, as it would be the only port of its kind west of the Mississippi River.

The project, already under construction, puts one of the major ports in the West Side near the lake. Community and environmental groups argue that the influx of trucks will increase air pollution and traffic and that the port will not only disturb nearby waterfowl management areas but will also pave over large amounts of sensitive wetlands alongside the lake.

Accordingly, the project presents a very real danger to both West Siders and Great Salt Lake, and since its inception, the project has been objected to by local community members, environmental groups, and Salt Lake City itself.

The passage of the bill that authorized the project, described as “hastily passed,” a “state takeover”, and even a “land grab” by the then-Salt Lake City mayor, resulted in protests and arrests. Jeffrey Langley Jr., writing for the Utah Daily Chronicle, highlighted many of the issues of the port’s approval process. As Langley noted, the Utah Legislature has shut citizens out of sub-committee meetings about the project, and lawmakers even had a mysterious, massive rewrite of the bill just a few days before passage.

In a joint letter, the chairs of all six West Side community councils called out both the substance of the bill and the process used to pass it, noting both “had contributed to a familiar narrative: that residents of West Salt Lake City routinely get bowled over by the wealthy and powerful.” All semblance of procedural justice had failed, with the influence of corporations and industry overshadowing any local resistance.

The Utah Inland Port Authority (UIPA), a quasi-governmental agency in charge of the project, continues to push ahead with its plans, citing the potential for the project to bring manufacturing and logistics jobs to the region. In fact, the project is even growing, with additional project sites being approved throughout the region.

Laura Briefer, Director of Public Utilities, a department of Salt Lake City that manages drinking water, wastewater, and stormwater, has seen the discontent around the project firsthand. She notes that the project was “a top-down decision.”

After what was essentially a legislative coup, local communities were left to deal with the fall out. “We’re trying to pick up the pieces and find ways for people to be heard, and to implement policies and actions that reflect that,” Briefer states.

As seen, that’s easier said than done. Residents in Tooele County, for example, have raised concerns at UIPA meetings that community feedback was making no impact on recently approved Inland Port projects—projects that seemed already long-decided by those in charge.