Harvard Law School’s Graduation Propaganda

How public interest messaging paints a misleading picture of HLS

Frank Obermeyer

May 20, 2024

“We’ve learned all these new skills and met all these cool people,” one student nostalgically shared in the Harvard Law School 2023 Commencement Day video. “Now we get to go out into the world and work on the causes that we care about.”

It’s a sweet sentiment. And if you attend a Harvard Law Class Day or commencement ceremony—with its public service and access to justice awards—you may leave with the impression that most graduates will go on to be public defenders, government servants, or civil rights litigators. Unfortunately, the employment data doesn’t match the rhetoric. If that student is right—if HLS graduates truly go on to work on the causes that they care about—then our classmates must really care about writing contracts for and litigating on behalf of corporations. Clearly something’s missing.

During 2023’s graduation messaging, about half of career aspirations that were highlighted were public service related. In reality, only 12% of non-clerking graduates are working in public interest jobs. To make matters worse, this public interest boasting occurs while clinical workers are voting to unionize in response to what some have called a “background of disinvestment” in clinical programs and instructors. While our graduation ceremonies undoubtedly should celebrate our classmates going into public service, these students’ efforts do not absolve Harvard of the criticism that it has yet to live up to its commitments to “the advancement of justice and the well-being of society.”

“A Presumably Bright, but Unpredictable Future”

In May, Harvard Law School will send another batch of lawyers into the world. After three years of hard work—and an average of $169,000 in student debt—graduates should be excited to put their new legal skills to use. Administrators, ready to send off another troop of happy customers, are taking care to ensure that this year’s Class Day and commencement ceremonies are meaningful. Here’s what you can expect for this season.

In the weeks leading up to commencement, the school will start highlighting some of our classmates’ plans for post-graduation, taking care to show the breadth of career possibilities available to HLS graduates.

In 2023, Michelle Yeoh offered graduates some rules to live by as they “dive headfirst into a presumably bright, but unpredictable future.”

At Class Day, we can certainly expect an impressive guest speaker. Past speakers have included Cory Booker, Mindy Kaling, and Larry King. 2024’s Class Day welcomed Secretary of the Interior, Deb Haaland, one of the first Native American women elected to Congress.

Whomever is chosen, we can look forward to hearing their advice for our graduates. 2018’s guest, Senator Jeff Flake, challenged the class to stand in the way of “forces that would threaten the institutions of liberty and tear us apart.” In 2023, Michelle Yeoh offered graduates some rules to live by as they “dive headfirst into a presumably bright, but unpredictable future.”

Michelle Yeoh at Cannes in 2000.

We’ll hear from the Dean of the Law School at both Class Day and commencement. Though it’s unclear who will permanently take John Manning’s role since the shake up resulting from Claudine Gay’s ousting, we can expect similar sentiments from Interim Dean John Goldberg as others have offered our newly minted Harvardites.

Goldberg will almost certainly remind them of the laudable number of pro bono service hours they accumulated while in school. Class of 2023 put in 385,000 hours of pro bono work—up nearly 10,000 hours from the class of 2018 and 7,000 from the Class of 2022.

He may encourage students to not forget why they came to law school, just as Manning did in 2019. Goldberg may, like Manning in 2022, proudly remember how the class “showed up to defend the marginalized, the vulnerable, those who would not otherwise have been able to have a lawyer, and who needed someone on their side to ensure that they received justice.”

The Law School will also take time to honor some of our most impressive graduates in the form of various “Community Awards.” The Kristin P. Muniz Memorial Award will go to an impressive clinical student in the Criminal Justice Institute. One or more students will be honored by the Clinical Legal Education Association for their outstanding public interest commitment.

In 2018, a record three students were honored with Andrew L. Kaufman Pro Bono Service Awards. In all, at least four students will be honored for their dedication to pro bono, clinical, or justice work.

With all these dedicated student leaders, racking up all these pro bono hours, and heading off to jobs across the public and private sector, the loved ones of our graduating class will surely think that the Dean had nothing to worry about when he encouraged graduates “not to forget the person you described to us in your applications.” If these students don’t still want to “make the world better,” then who does?

Or does the Dean know something that the audience doesn’t? Maybe Manning’s warning speaks to his knowledge of the actual outcomes of HLS grads. Excluding students heading to clerkships, over seventy percent of Harvard Law grads will leave Cambridge to work for big law firms—hardly the “unpredictable future” that Yeoh mentioned in her Class Day speech.

Over seventy percent of Harvard Law grads will leave Cambridge to work for big law firms—hardly the “unpredictable future” that Yeoh mentioned in her Class Day speech.

In the Class of 2023, for every graduate that works in public interest, six work for big law firms. Even if we include government and education work with public interest, there are still four big law graduates for every one heading to public service.

Comparing these statistics to the commencement programming above, public interest work receives a disproportionate amount of publicity in Harvard messaging compared to the actual work of its graduates. Worse still, placing public interest work on a pedestal while clinical professors complain of being treated like “second-class” academics seems, at best, out of touch.

Sure, everyone bends the truth a little bit. And what would the alternative be? An award for the student most dedicated to white collar defense? I don’t think so. But we can’t neglect the effects of these awards.

When an institution like Harvard Law School oversells its contributions to society, it deflects attention from what Harvard could be doing better to address systemic harms. Harvard’s public service image must be looked at critically, through a similar lens that students have pointed at big law pro bono work. This is especially so while clinical staff are currently fighting for better recognition, pathways for advancement, and pay within the Law School.

Though we should certainly celebrate the public interest work of our classmates, it does have the collateral effect of masking the reality that most of America’s top law school graduates will not go on “to make our world better, more compassionate, more equal, more just, more ethical, and more united,” but will instead serve the nation’s most powerful individuals and corporations. This practice also washes Harvard’s hands of any role it may play in pushing candidates toward big law firms.

Disproportionate Representation

Back to the 2023 Commencement Day video, the career goals shared can shed a light on how Harvard manages its marketing. One student was passionate about tax law, another was excited to work in tech policy, a third couldn’t wait to start his own business.

Some explicitly wanted to help others. One student hoped to “elevate the needs of the communities who often are most impacted by legal systems.” Another mentioned how lucky they felt that at HLS they can go “straight into civil rights after law school.”

In all, the careers of 2023 graduates mentioned in the commencement video included the following: tax law, tech policy, entrepreneurship, three focused on civil rights. That’s just one out of six going to a traditional big law firm.

Of the nine Community Awards to be doled out at graduation, two are dedicated to Ames Moot Court competitors, three go to students who contributed to the HLS community, and the remaining four awards are given to students dedicated to pro bono, clinical, or justice work.

For those counting at home, that’s 44% of the awards announced at graduation going to public interest causes. Of the graduates highlighted in the pre-graduation messaging, two-thirds are entering civil rights or policy work (including government enforcement, plaintiffs’ side civil rights, voting rights, and tech policy).

In the weeks leading up to the 2023 commencement, the school highlighted six other individuals, of which two were heading to clerkships, one was starting a prestigious Skadden Fellowship focused on immigration, one was returning to the Army as a Judge Advocate General focused on criminal justice reform, one was heading to a law firm, and one would be returning to Mongolia. That’s only 17% law firm representation.

All of these students should be proud of their accomplishments. And to be clear, each graduate should be free to choose their careers based on their individual interests and circumstances. However, it’s important to note the effects these student testimonials have on observers. We must understand them in the context of the actual employment outcomes of Harvard Law graduates and the current state of the legal profession.

The “Endemic Malaise of Lawyers”

England spends “13 times as much per capita and Canada spend[s] three times as much per capita as the United States does on civil legal aid.” As Pete Davis has documented in Our Bicentennial Crisis, there is a significant access to justice gap in America. By 2018, U.S. funding had increased by roughly $350 million, accounting for inflation, over 2005 funding.

Although funding has increased since Davis’ reporting, the access to justice gap persists. The Legal Services Corporation, America’s largest funder of civil legal aid, estimates that low-income Americans receive insufficient legal help for 92 percent of the legal problems that substantially impact them.

Senator Jeff Flake speaks at Harvard Law School Class Day. Photo by Jacqueline S. Chea, from The Harvard Crimson

Legal aid funding is consistently Congress’s chopping block. Jeff Flake, the 2018 Class Day speaker mentioned above, voted to fully defund the Legal Services Corporation in 2009, 2011, and 2012. It’s no surprise that Pete Davis—then a 3L at HLS—publicly criticized Flake’s work to “advance the war on civil legal aid.”

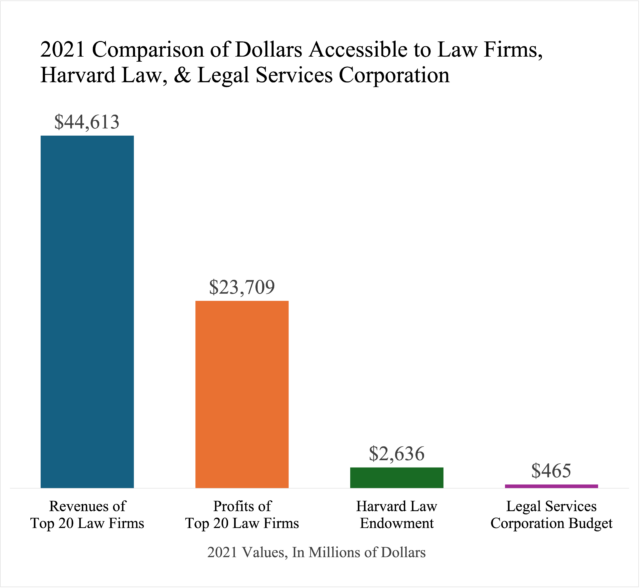

Revenues and Profits of Top 20 law firms dwarfs LSC funding.

If you follow the money, the difference in legal support going to the powerful as opposed to the poor is overwhelming. The 20 most profitable law firms made over $23 billion in profits in 2022, while only 2.45% of lawyers’ billable hours are in assistance of folks with limited means. In all, revenue of the top 20 law firms is nearly 100 times greater than the funding of Legal Services Corporation.

Profits and revenues by America’s largest law firms.

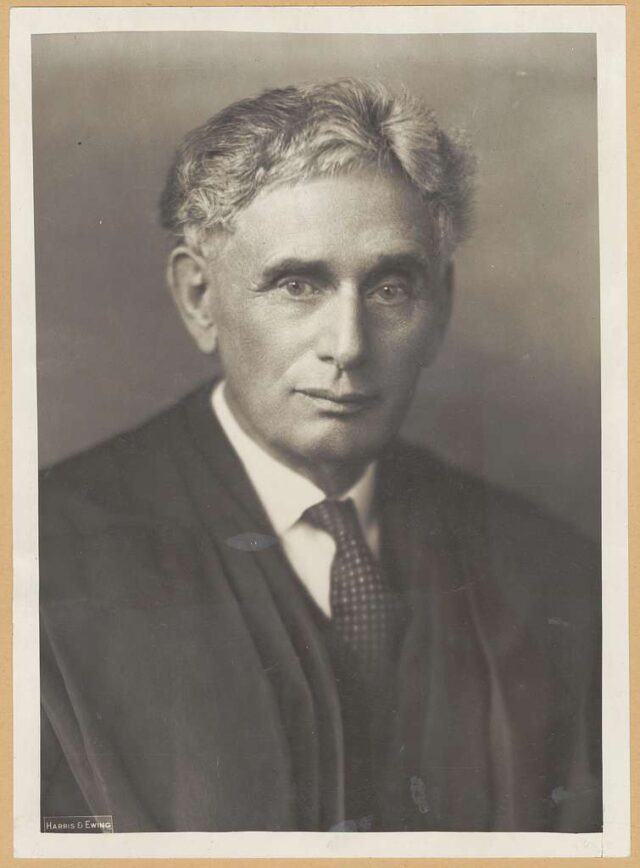

This isn’t a new problem. The American legal profession has been critiqued for its indifference to the poor for well over 100 years. In 1905, Louis Brandeis accused the bar of disproportionately representing the powerful. “[L]awyers have,” he said, “neglected the obligation to use their powers for the protection of the people,” and have “allowed themselves to become adjuncts of great corporations.”

A decade or so later, Reginald Heber Smith cast a scathing indictment against the profession, arguing that “the traditional method of providing justice has operated to close the doors of the courts to the poor, and has caused a gross denial of justice in all parts of the country to millions of persons.”

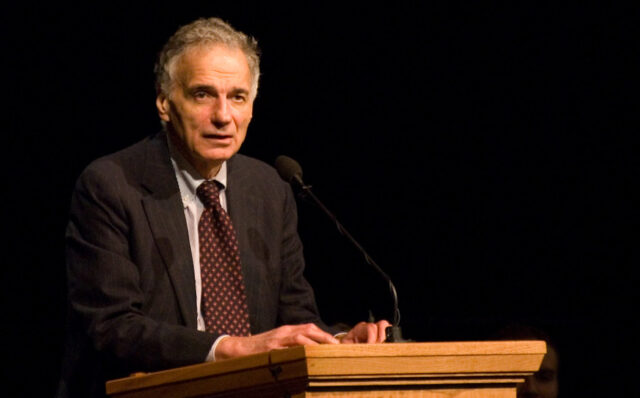

Ralph Nader called this the “endemic malaise of lawyers . . . that 90 percent of them serve 10 percent of the people.” He’d be echoed by Jimmy Carter in a 1978 speech to the Los Angeles Bar Association. “We are overlawyered and underrepresented,” said Carter. It’s not simply about money, Nader would go on, “it is a choice in favor of that affluent class whose legal and illegal interests are often directly adverse to the bottom 90 percent of the citizenry. This maldistribution of lawyers in a highly legalistic society fortifies powerful interests.”

Ralph Nader called this the “endemic malaise of lawyers . . . that 90 percent of them serve 10 percent of the people.”

Harvard has been singled out for its contributions to this malaise. In 1992, Granfield called attention to this issue in his book Making Elite Lawyers. 25 years after Grandield, Pete Davis published Our Bicentennial Crisis: A Call to Action for Harvard Law School’s Public Interest Mission. Critics argue that, because Harvard has “dominated American legal education” and has a mission explicitly dedicated to the advancement of justice, it should be doing more to shape the industry to address underrepresentation of the poor.

Ralph Nader, speaking at BYU’s Alternative Commencement. Photo by Don LaVange.

“A Progressive Step”

“There was only one clinic when I was [at Harvard Law] . . . there are now over 30,” admitted Ralph Nader, a Harvard Law graduate who has openly criticized the school’s corporate focus, “that’s a progressive step.” Nader is right, there have certainly been positive steps. In a 2003 publication celebrating Harvard’s Legal Services Center, Shira Shaiman retold some of the history of clinical work at HLS.

Although the Harvard Legal Aid Bureau has existed since 1913 to provide legal services to low-income folks in the Boston area, students have continually demanded more. In the 70s, less than 5 percent of HLS graduates entered legal aid or public defender work. In 1971, Harvard hired Gary Bellow to start up a clinical program in response to student complaints. Over the next three decades, Bellow and his wife Jeanne Charn would “establish one of the largest and most successful clinical programs in the country.”

“There was only one clinic when I was [at Harvard Law] . . . there are now over 30.”

In 2002, the law school implemented the pro bono graduation requirement after students showed “overwhelming” support for the initiative. Students saw the requirement as a way to “benefit Harvard’s public image, promote ethical responsibilities of lawyers, and have a positive impact beyond the law school.”

But this progress was not without setbacks. In 1989, Dean Robert Clark eliminated the law school’s two public interest advising positions as a cost cutting measure, saying that the roles had served only a “symbolic, guilt-alleviating” purpose. The school would reopen public interest advising just a year later, after national outcry.

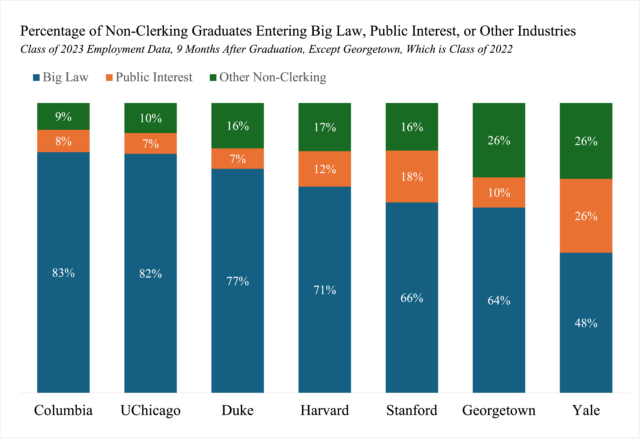

Today, Harvard maintains the 50-hour pro bono graduation requirement and offers 25 in-house clinics alongside external clinical opportunities. By some metrics, these initiatives have worked. A sample of employment data for the class of 2023 across seven law schools is helpful to understand where Harvard falls.

Class of 2023 employment data from seven major law schools.

Although Harvard still sends more total graduates into big law than every school except Georgetown, Harvard only trails Yale and Stanford in percentage of students pursuing public interest work. For many students, clinical work is a central part of their law school experience. And even if students don’t end up in public services, clinical work provides notable benefits.

“I can’t imagine what it feels like for people who are working full time while trying to navigate that system.” Travis Cabbell is the former president of the Harvard Legal Aid Bureau (HLAB), who shared some of his experiences representing victims of wage theft. Helping clients is central to the benefits of clinical work. “If I can bring justice to just one person, that is enough because you made one person’s life better.”

Our justice system often assumes that both sides of a dispute are represented, so folks who go in without a lawyer are at an extreme disadvantage. “These systems are not set up for people to navigate without lawyers,” shared Esme Caramello, Clinical Professor and Faculty Director of HLAB, “clinics are a way for law schools to contribute resources towards leveling the imbalance of power.”

Some would go further. “110% they have a moral obligation to create places that give back to the community,” says Rebecca Greening, a clinical instructor in Harvard’s Family Justice Clinic. “This institution of immense wealth and privilege has a moral imperative to serve the community.” Whether or not Harvard feels this moral obligation, administration at least sees the importance of clinical work for the recruitment and benefit of students.

“I’m one of the people who went to HLS and in my interview I said I wanted to join HLAB,” shared Cabbell. Cabbell came to law school specifically to advocate for economic justice, after experiencing wage theft firsthand and working with labor organizers as an undergrad.

Where are the people in these cases? Where is the human element of any of this?”

Caramello shared some other reasons why students join HLAB. “There are people who want to go into legal aid. There are people who just want to become litigators.” Some just “want to be in a mission-driven community of likeminded people.” The list goes on.

Clinics also contribute to legal learning. To some, the unique value of practical work cannot be replicated in the classroom. “I believe you learn better in practice,” said Caramello, “even practicing in simulated environments is not even close to the kind of learning that occurs if you are in a real-life situation.”

Greening offered a similar sentiment from her time at Northeastern University School of Law. Coming from a social work background, she struggled to adjust to the Langdellian learning method of law school. “I was like, what are we doing here? Where are the people in these cases? Where is the human element of any of this?” It was only in her summer internship at Harvard’s Legal Services Center that things started to click, she thought: “This is how it’s going to work. I’m going to see how this law applies to this person’s life.”

Harvard Legal Services Center Logo.

Many students come to law school both to learn doctrine and to think critically about the legal system. Apart from the practical experience of drafting and arguing, Caramello noted how clinical work helps students engage with these broader systemic questions in a more refined way. “You can have these theoretical conversations in law school all the time, but it’s only when you start trying to apply them in the real world, that you start to really refine your thinking.”

Despite the many benefits that clinical work provides clients, students, and the broader legal system, some critics still argue that Harvard can’t see the forest from the trees. “It’s mostly legal charity,” added Nader, “There’s a big difference between legal charity and legal justice. Charity is a food kitchen. Justice is adequate livelihoods for workers so they don’t need to go to food kitchens.”

An “Institutional Thumb on the Scale”

With all these positive benefits of clinical work, why do students still overwhelmingly move towards law firms? The State Bar of California calls it “public interest drift”—students abandoning the public interest aspirations with which they entered law school.

Debt could be one cause of this drift. Though Harvard boasts a Low Income Protection Plan, students from lower economic means regularly feel drawn to the higher salaries of big law. This is a reasonable decision for many graduates, especially students of color.

“Can I survive on a public interest salary?”

Yale Law School’s public interest FAQ offers insight into the mind of a young law student. The page mentions how some students “are lured by the tremendous amount of money in the private sector and figure they’ll earn a large salary for a few years, then come back to public interest.”

“Can I survive on a public interest salary?” was a common enough question to deserve a paragraph-long answer. The salary issue may simply be a symptom of framing. Compared to the salaries of their peers heading to law firms, the average public interest salary does look measly. But to many Americans, $60,000 dollars would be a welcome salary.

Vinny Byju has called attention to Harvard’s “institutional thumb on the scale,” which leads students straight to big law. This scale tipping takes several forms, including making law firm recruiting the default option for 1Ls. Many students agree, feeling that “[t]he defaults are set up in a way that you slide into working at these firms without much thought.”

In all, most critics of Harvard’s big law pipeline focus their attention on the subtle, systemic factors that pull students to law firms. Though others think Harvard’s classes should do more to foster a sense of justice in students. “There’s no inculcating the understanding that the purpose of law is justice,” says Bruce Fein an HLS alumnus and constitutional scholar.

“The defaults are set up in a way that you slide into working at these firms without much thought.”

In Making Elite Lawyers, Granfield discussed clinical work with a law student who largely echoed the praise mentioned by today’s students: “client contact, making a difference in someone’s life, and helping people who really needed legal help.” But when asked if he’ll continue doing legal services work in the future, the student frankly answered, “unlikely. You really can’t accomplish all that much, you have few resources, and the pay is pitiful. I’m going to work at a corporate law firm in Philadelphia.”

It seems things haven’t changed much since the 90s. But even if Harvard can’t control the career choices of its graduates, it can at least invest in the clinical staff that provide such a meaningful part of many students’ legal education.

Second-Class Citizens

“The Law School’s leadership is constantly reminding us that we are regarded as second-class citizens instead of serious colleagues engaged in a co-equal and equally significant academic pursuit,” John Fitzpatrick told Harvard Magazine. Fitzpatrick is a senior clinical instructor at the Harvard Prison Legal Assistance Project who celebrated 25 years with the university in 2023.

There are certainly some differences between clinical and podium roles. At Harvard, clinical instructors aren’t required to teach traditional classroom courses or produce scholarship. But don’t be mistaken, different does not mean lesser. Clinical instructors fill a uniquely challenging role of being both skilled practitioners and dedicated teachers.

“A lot of doctrinal faculty just don’t have [as many practical] experiences because they came to academia at young ages,” says Cabbell. “Learning from clinical instructors has been very enlightening because they may have done different work, and they bring that to the work that they do with us.”

Practical experience is the only difference, as job responsibilities diverge greatly between the two groups. “I have 10 jobs,” says Greening, “you’re teaching, you’re practicing, you’re program-developing, you’re grant-reporting. You’re doing all these million things.” All this, she says, with no dedicated administrative support for her clinic.

“I have 10 jobs,” says Greening, “you’re teaching, you’re practicing, you’re program-developing, you’re grant-reporting. You’re doing all these million things.”

Funding is also a major issue for clinics, as they are primarily funded by grants. “clinics are really put in the position of having to self-fundraise and be on these soft funding cycles,” Greening said. “This makes people’s jobs insecure.”

This need to fundraise not only places more work on the already strapped clinical staff, but it could also stall progress. “If they had solid support of the institution,” Greening told me, “clinics would be much more able to innovate or to push the envelope.”

It’s more than just funding. “What is really different at Harvard than other institutions is that clinical faculty do not have full governance rights at the law school,” says Greening, referring to the process by which the law school governs its academic programs and curriculum. Though clinical faculty are allowed to vote on certain matters, they are actually made to leave the room for other types of governance decisions. “There’s a serious commitment to hierarchy here that is very institutionally held, and enforced, and reinforced.”

Greening and Fitzpatrick are clearly not alone. In April of 2024, law school clinical staff overwhelmingly voted to unionize. When asked her thoughts on 95% of clinical workers voting in favor of the union, Greening wasn’t surprised. “What do you do when you feel disempowered, or you’re looking around your colleagues and they’re not being treated right?”

The union’s next steps are to elect a bargaining committee and begin figuring out their priorities. That said, Greening seems to have many ideas for how the university could improve, including addressing compensation, limited career pathways, and job mistitling. One solution would be creating more paths to clinical professorships.

“There’s only one place to go from our job: a clinical professorship. They dole them out very meagerly.” For instance, the Legal Services Center is home to six clinics, but has only one clinical professor. For comparison, the Harvard Legal Aid Bureau has three practice areas but has two clinical professorships. This lack of advancement also affects clinical instructors’ ability to make lateral moves. For instance, if a clinical instructor wanted to change jobs, they could be limited to joining the other university as a “fellow,” basically at the entry level.

This problem isn’t limited to Cambridge. How Harvard treats its clinical instructors affect other law schools as well. When Harvard structures its programming in a certain way, other schools follow. Harvard has the opportunity to once again lead law schools by example, just as it did when it hired Gary Bellow in 1971.

Brandeis’ Call to Action

Greening wants the status of clinical legal education to be elevated in the eyes of students. Referring to the publicity Harvard gives to clinical work, she told me, “I think that’s good. It’s communicating that the institution cares, that these are experiences we want you to have.”

“It really demoralizes the people working in the clinics to feel like they’re using us to recruit students or they’re using us to get donations to the law school. And, you know, I’m struggling to pay my rent. I can’t afford childcare.”

Most would agree that Harvard should keep promoting pro bono and clinical work. It celebrates our most dedicated students, it’s inspiring to others, and it provides a platform for the political and social movements that these lawyers support. “But to do that with a background of disinvestment,” says Greening, “that’s where I have a problem.”

Justice Louis Brandeis

If Harvard wants to promote this part of its curriculum, it should provide proportionate funding to this type of work and support the hardworking educators that make clinical work possible. “It really demoralizes the people working in the clinics to feel like they’re using us to recruit students or they’re using us to get donations to the law school. And, you know, I’m struggling to pay my rent. I can’t afford childcare.”

Harvard Law’s stated mission is “to educate leaders who contribute to the advancement of justice and the well-being of society.” It is hard to imagine a segment of this university more dedicated to this mission than the hardworking folks who staff our clinical programs. If the law school truly believes in this mission, it needs to put its money where its mouth is.

Brandeis offered a warning the Harvard Ethical Society: “We hear much of the ‘corporation lawyer,’ and far too little of the ‘people’s lawyer.’”

In 1905, Brandeis offered a warning the Harvard Ethical Society: “We hear much of the ‘corporation lawyer,’ and far too little of the ‘people’s lawyer.’ The great opportunity of the American Bar is and will be to stand . . . ready to protect also the interests of the people.”

Harvard has undoubtedly heeded the first half of the quote. This graduation season, we will scantly hear of the corporate lawyer, and deservedly give credit to our hardworking classmates who are willing to be lawyers of the people. Unfortunately, with only 12% of our non-clerking graduates heading to serve the public interest, while 70% flock to the same big firms in the same few cities, Harvard has much more to do to address the second half of Brandeis’ call to action.

![[F]law School Episode 4: Public Interest Propaganda](https://theflaw.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/HERO_OBERMEYER-640x427.jpeg)