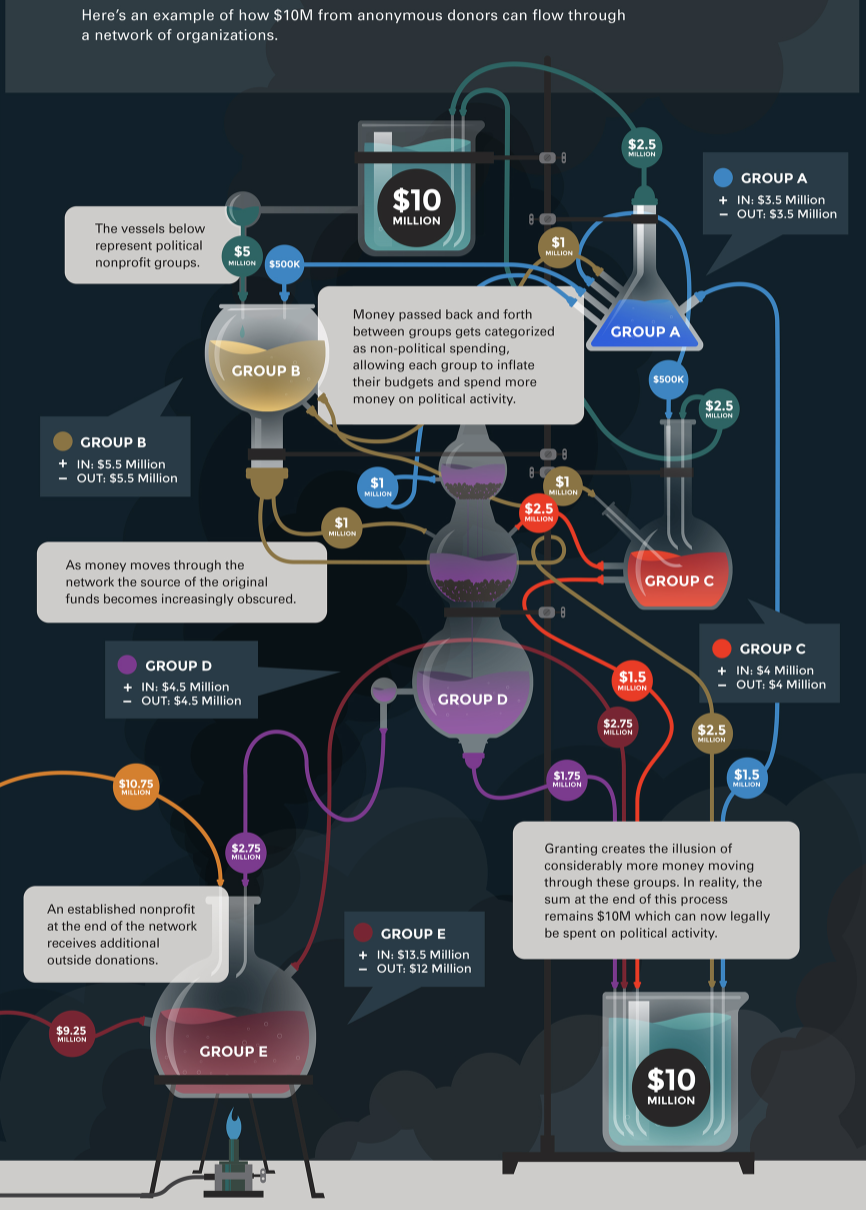

C4s are not effectively regulated. Since 2015, “thousands of complaints have streamed in — from citizens, public interest groups, IRS agents, government officials and more — that C4s are abusing the rules, but the agency has not stripped a single organization of its tax-exempt status for breaking spending rules during that period.” There are 3 main factors contributing to this lack of enforcement.

The first relates to a grave lack of resources. Despite Citizens United unleashing unlimited political spending, Congress reduced the IRS budget. While the IRS Exempt Organization Unit had to deal with an 80-fold increase in the number of politically focused organizations seeking approval as C4s, their staff and resources were being reduced. This combination of skyrocketing demand and diminishing ability to meet the demand was predictably disastrous. In a 2013 email, Lois Lerner, then-head of the Exempt Organizations Unit of the IRS wrote that her “level of confidence that we are equipped to do this work continues to be shaken,” and that she “[didn’t] even know what to recommend to make this better.”

While the IRS Exempt Organization Unit had to deal with an 80-fold increase in the number of politically focused organizations seeking approval as C4s, their staff and resources were being reduced.

To make matters worse, not only was Lerner’s unit overwhelmed by a surging number of C4s to oversee, the Exempt Organizations Unit also had an extremely tedious process that they had to follow in order to investigate the C4s under their purview. To even initiate an investigation into an exempt organization, IRS officials had to go through six time-intensive steps. Why would anyone design such a convoluted system? Perhaps the IRS wanted to protect themselves from scrutiny from the very individuals in Washington who benefit from the C4s that the IRS investigates. Roger Vera, who was in charge of overseeing investigative referrals of exempt organizations, stated that “[the IRS] made the system so complicated because they didn’t want the inspector general to come in and say, ‘Hey, you only looked at two or three cases and they’re all a certain political group.

This fear of scrutiny and accompanying tedious investigative process rendered the Exempt Organization Unit almost entirely powerless when it came to dark money groups. The three-year time limit for acting on a C4 complaint often expired before the IRS could take any action. An investigation by the Senate Finance Committee found that almost every complaint that was filed between 2010 and 2014 was bogged down before field agents could even initiate an investigation into the C4 groups.

The second reason why oversight and enforcement of 501(c) nonprofits has been limited is because past attempts to solve the problem have resulted in extreme backlash and complete vilification of IRS employees. Starting in 2010, the Exempt Organization Unit tried to overcome their lack of resources and cumbersome investigation process, by creating a shortcut. If a group applying for C4 status had a keyword in their name that sounded political, they flagged it for extra attention. In 2013, the Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration released a report about this use of keywords, and indicated that “tea party” and other conservative terms were being targeted at a disproportionate rate. Mind you, it appears that the only denial of tax-exempt status by the IRS that happened under this scheme was to a progressive group. Nevertheless, chaos ensues.

Conservative-leaning media outlets react in outrage. IRS commissioner Steven Miller is forced to resign. House Republicans have a field day accusing the IRS of spearheading a partisan assault against conservative groups. In one hearing, Rep. Kevin Brady, R-Texas stated that “this is the most corrupt and deceitful IRS in history.” Hearings on the subject continued intermittently for four years and the IRS ultimately spent 98,000 hours in staff time responding to the congressional investigations.

The situation escalated further when the Republican-led House Oversight Committee charged Lois Lerner, head of the Exempt Organization Unit, with Contempt of Congress for claiming a 5th Amendment Right to refuse to testify. As Lerner faced potential prosecution over the charge, IRS officials were reeling from the intense backlash. One IRS employee explained to ProPublica reporter Maya Miller that during the time of the investigation “I was scared of being pilloried, dragged to the Hill to testify, getting caught up in lawsuits, having to sink thousands of dollars in attorneys bills that I couldn’t afford, and having threats made against me or my family…I locked down my Facebook page. I deleted all personal Twitter posts. I stopped telling people where I worked.”

Image of Lois Lerner as she pleads the fifth

Lois Lerner was never charged, and the Senate Finance Committee and Department of Justice each came out with reports concluding that the use of keywords was a result of lack of resources, bureaucratic restraints, and mismanagement, as opposed to being politically motivated. But the crusade was not over. Just a year after these reports were released, the House Oversight and Government Reform Committee voted 23-15 to censure Koskinen as a result of the keyword scandal, and called for his removal from office as well as the forfeiture of his government pension and other federal benefits for which he is eligible.

Four years after their initial report exposing the use of keywords, the Treasury Inspector General of Tax Administration released a new report noting that the Exempt Organization Unit also used keywords targeting progressive groups, including terms such as, “green energy,” “medical marijuana,” and “occupy”. But by this point in time, nobody was still paying attention. The dust had settled, people moved on, and the damage was done. As Senator Whitehouse wrote in his book entitled The Scheme, “by the time the inspector general investigation confirmed that the influence machine’s claims were bogus, the damage had been done and dark money had an avenue into politics that many feared to touch.”

The whole reason that the keyword search was necessary, besides lack of resources, was the fact that the IRS had no clear guidance as to what “primary purpose” meant (remember, this is a requirement for C4s, which are intended to be social welfare organizations). Therefore, as Congressional hearings were unfolding, the inspector general set out to define primary purpose. IRS Commissioner Koskinen initially proposed that C4s should be barred from any campaign-related activity. But in light of Congressional opposition, Koskinen instead proposed a percentage-based definition of “primary activity” – the 50% rule. Congressional Republicans not only disapproved of this new suggestion, but they disapproved of any attempts to define “primary purpose” and restrict C4 political activity.

In December 2015, Republican House leadership inserted a rule into a budget appropriations bill banning the IRS from issuing or finalizing any regulation “to determine whether an organization is operated exclusively for the promotion of social welfare.” This language remains in budget appropriations bills to this day. So to answer the question of why doesn’t the IRS do more to constrain C4 political activity? It’s Because Congress has literally barred them from doing so.

Lastly, it’s time to discuss Corporations. In theory, the SEC could alter disclosure requirements such that Corporations would have to reveal who they make political contributions to and in what amount. Such disclosure rules would make a lot of sense in the context of corporate law, which operates under the theory of shareholder primacy – which holds that as owners of corporations, shareholder interests should be Corporation’s highest priority. Surely, highest priority includes a right to know when and how the Corporation’s money is being spent to influence politics? Apparently not. In a move that might sound familiar, Congress used a budget appropriations bill to ban the SEC from issuing corporate political spending disclosure rules. That ban remains in place to this day.