St. Croix’s indigenous Taíno name is Ay Ay; the island was originally inhabited by the Taíno and at least two other Indigenous groups. Christopher Columbus landed on St. Croix in 1493, and it was the site of the first documented conflict between Indigenous people and European colonizers. Over the next 200 years, the Indigenous inhabitants were killed and driven out by Europeans, leaving the island virtually uninhabited.

The Danish West India Company purchased St. Croix in 1733, and the island’s colonial economy was built on the labor of enslaved Africans, who were forced to work on Danish sugar plantations.

Slavery officially ended on St. Croix in 1848, but plantation owners were still able, by law, to force formerly enslaved workers into exploitive labor contracts. In 1916, Denmark sold the Virgin Islands to the U.S. in exchange for $25 million in gold.

Today, the Virgin Islands’ population is 76% Black, and many of its Black citizens are descended from Africans who were kidnapped by Europeans and taken to the Caribbean.

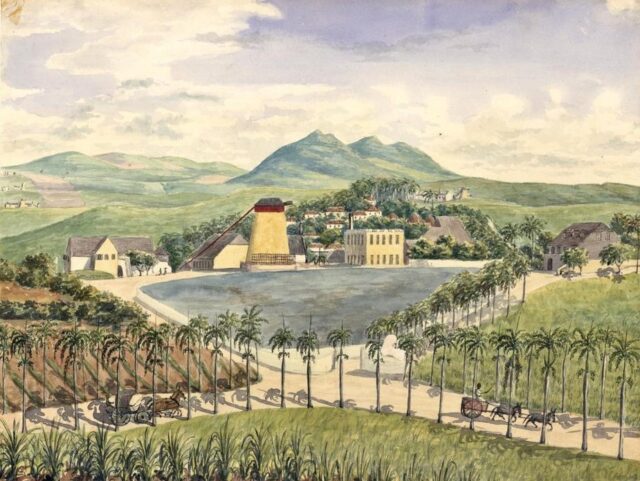

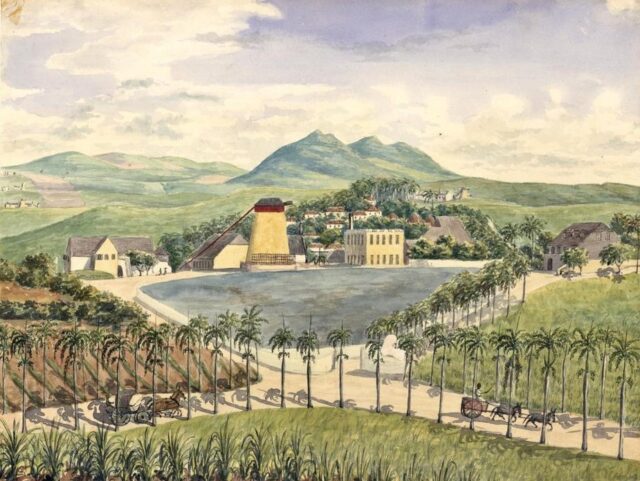

Painting by Frederik von Scholten of a St. Croix sugar plantation, circa 1840. Source: Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=57063864.

St. Croix remained a primarily agricultural economy until the refinery opened in 1967. Originally owned by oil giant Hess Corporation, the refinery soon became the largest in the world. Hess later reached a joint ownership agreement with Petroleos de Venezuela, and the refinery became known as HOVENSA. It was one of at least twelve refineries that were built by U.S. companies in the Caribbean between 1950 and 1970.

As oil production and demand grew throughout the 20th century, the Caribbean proved a convenient geographic hub: oil produced in Venezuela and even Nigeria could pass through on its way to U.S. markets, and Caribbean refineries could charge a better price than those in the contiguous U.S.

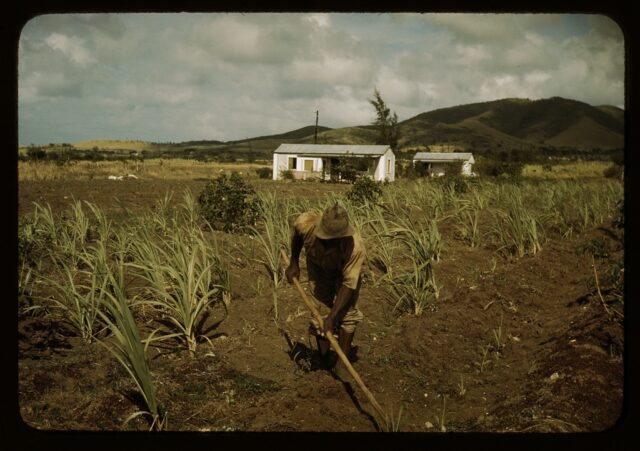

The refinery’s opening was a product of a plan by the Virgin Island’s government to transform St. Croix’s economy from agricultural to industrial. The territorial government was inspired by “Operation Bootstrap,” a set of initiatives Puerto Rico adopted in the 1940s to modernize its economy. Using tax breaks and subsidies, the Virgin Islands secured deals to bring the HOVENSA refinery, as well as a Harvey aluminum plant, to St. Croix.

David Bond, an anthropologist at Bennington College and an expert on the refinery, explains that these modern industries were marketed as opportunities for Crucians to finally achieve freedom and prosperity. Government advocates for the industrial plan emphasized the links between the agricultural economy and the island’s history of slavery.

A St. Thomas newspaper suggested that the new industries would “remove the social, economic shackles which have prevented progress on St. Croix.” The plan was billed as good for labor, too: one labor union representative described it as “one of the greatest things” to happen on the island. Support was far from universal, however, and thousands of Crucian farmers protested the industry deal.

HOVENSA’s economic successes translated into big benefits for the Virgin Islands. Revenues from the refinery came to make up 20% of the Virgin Island’s annual budget, providing funds for government programs and cementing the territorial government’s dependence on the refinery. At the holidays, Hess trucks fanned out to St. Croix schools, making sure every kid on the island got a Christmas gift from Hess. Jobs at the refinery paid well and created a new middle class on the island. Sommer Sibilly-Brown, a lifelong

St. Croix resident and founder of the Virgin Islands Good Food Coalition, explained to me that many Crucians wanted their kids to grow up and go work at the refinery. “[I]t seemed like it would afford them the ability to send their children to private school, you know, to purchase a home . . . that was a nice, stable life.”

But many of the people who enjoyed the refinery’s hiring boom were not Crucians. Refinery management came from Texas, Louisiana, and New Jersey. Tradesmen with expertise in oil came from Trinidad and Aruba, and laborers came from the eastern Caribbean. The influx of outsiders to staff the refinery permanently changed the demographic mix of the island.

When the refinery opened, CEO Leon Hess bragged about its competitive advantages in the oil market: the company’s innovative operating strategy, its superior storage facilities, and its strategic location near cheap Venezuelan oil. But what really made the refinery attractive were the tax breaks it secured and the regulatory advantages St. Croix offered, as Dr. Bond uncovered in a recent article.

Unlike similar Caribbean locations, St. Croix was American, so the oil wasn’t subject to steep import tariffs. But the refinery also enjoyed a level of freedom from government oversight that was unavailable on the mainland. In 1966, the year refinery construction began, the Virgin Islands Industrial Incentive Board wrote, “word has gotten around Wall Street that corporations can get a businessman’s deal in the Virgin Islands,” free from anyone “peeking over [their] shoulder.”

“Word has gotten around Wall Street that corporations can get a businessman’s deal in the Virgin Islands,” free from anyone “peeking over [their] shoulder.”

The refinery’s business model and infrastructure were designed around non-accountability. The facility used pipelines to transport petroleum materials around the island: there were pipelines to carry the refined products to port for sale in the U.S., and pipelines to carry waste materials away for storage. The pipes carrying the valuable products for sale were built safely aboveground. The pipes carrying waste were built below ground, buried in salty sand where they quickly—and predictably—started rusting.

In 1982, the Environmental Protection Agency discovered the corroding pipelines were leaking hundreds of thousands of barrels of petrochemicals underground, some of which had formed a ten-foot layer that was floating on the island’s only aquifer. In 1994 EPA determined that all the pipes needed to be replaced, yet the facility continued operating.

Dangerous worker shortcuts were part of normal practice, too. Dr. Bond explained to me that because half of Crucians rely on rainwater cisterns for drinking water, air pollution problems on the island are also drinking water problems. Yet Dr. Bond collected stories from refinery workers who used the cover of darkness to vent benzene, a toxic pollutant that can cause cancer, anemia, and reproductive problems, into the air. Workers also recounted flushing mercury down drains, knowing that the drains flowed into bays frequented by local fishermen.

A close-up view of the St. Croix refinery. Source: Cumulus Clouds – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=2230167.

These practices continued unchecked until 2011, when St. Croix’s problems became so obvious that federal regulators could no longer ignore them. A series of refinery explosions, so loud they were heard from several miles away, cloaked the island in thick clouds of black smoke.

Internal oil spills triggered releases of noxious fumes that swept over the downwind neighborhoods and their 20,000 residents. The fumes sickened residents and caused dayslong school closures. EPA investigators were swiftly dispatched to the island. They exposed maintenance issues and problematic shortcuts, although several investigators also spent their evenings off at tropical themed parties with HOVENSA executive staff.

In 2011, EPA reached a consent decree agreement with HOVENSA for violations of the Clean Air Act. HOVENSA agreed to pay a penalty of $5 million, to spend $700 million on new pollution controls to reduce emissions from its refinery equipment, and to fund $5 million in projects to improve environmental health on St. Croix.

A year later in January 2012, HOVENSA announced it was shutting down the plant. Ms. Sibilly-Brown recalls the plant’s closure as a time of uncertainty. She had friends whose lives were built around working for the refinery, and her best friend, whose husband worked at the refinery, had to leave home to find work off the island. And no one knew what would happen to the polluted landscape as the refinery sat dormant.

In September 2015, the Virgin Islands government filed a lawsuit against Hess, claiming that its executives “conspired to strip the facility’s assets in order to leave the government with claims against a broke, polluted and inoperable refinery.”

The Virgin Islands government filed a lawsuit against Hess, claiming that its executives “conspired to strip the facility’s assets in order to leave the government with claims against a broke, polluted and inoperable refinery.”

The same day the government filed its lawsuit, HOVENSA filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy. Bankruptcy enabled HOVENSA to sell the refinery, which it did in December 2015 to Limetree Bay Ventures, a partnership between private equity firms Arclight Capital and EIG. Instead of fulfilling its obligations under the EPA consent decree, HOVENSA spent over $400 million maintaining the refinery’s operability so that it could be restarted by its new owners.

Many Crucians were unhappy about the prospect of reopening. Deanna James, president of the St. Croix Foundation for Community Development, explained to local newspaper St. Thomas Source that after the 2012 closure, residents were overwhelmingly resolved that “the refinery was part of the island’s past.” They believed they could find something new to power their economy.

But the years following the closure were undeniably difficult for the Virgin Islands. A year after closure, the unemployment rate on St. Croix reached 17%. The Virgin Islands’ GDP fell over 13% in a year. The territorial governor’s office warned of an energy affordability crisis (the refinery had subsidized electricity and gasoline prices on the island), an erosion of the middle class, and hundreds of millions in lost tax revenues.

In 2016, St. Croix’s child poverty level was 37%. And then Hurricanes Irma and Maria struck. Hurricane Maria destroyed 70% of the buildings on St. Croix, including the island’s only hospital, and it devastated the already-weakened economy. An additional 12% of jobs disappeared, and government revenues were cut in half.

The territorial government saw the refinery’s sale as an opportunity to revitalize the Virgin Islands’ crippled economy. When the territory’s then-governor Kenneth Mapp approved an agreement between the Virgin Islands and Limetree Bay, he promised that the refinery would bring hundreds of millions in revenue to the government to support public employee wages, add to the government retirement system, and provide public services to the community.

But many Crucians saw the agreement as a giveaway to Limetree Bay. The contract included at least fifteen different tax exemptions, including tax breaks that would have otherwise supported the reopening of St. Croix’s hospital, which has remained closed since the hurricanes.

Environmental protection fared no better in the reopening process. In 2017, Governor Mapp sent a personal letter to President Trump asking him to expedite the federal government’s environmental approval process. And the private equity owners of Limetree Bay had some advantages working in their favor: the managing partner of Arclight Capital, Daniel Revers, is a major GOP donor with ties to Trump. Revers traveled with President Trump to China in 2017 for the purpose of recruiting Chinese investors for the refinery.

This close connection raised concerns about regulatory capture, and EPA’s actions only aggravated those concerns. According to internal EPA emails, obtained through FOIA requests, EPA used Limetree Bay to try out a new “customer liaison concept” for interacting with regulated companies.

One EPA official, Robert Tomiak, regularly met with Limetree Bay and offered to “serve as their front door . . . for anything they need.” Under EPA rules, refineries that are closed for an extended period generally need to apply for a new environmental permit to start back up. But despite the refinery’s eight-year-long closure, EPA allowed Limetree to reopen using HOVENSA’s old permit.

View from the Frederiksted Hotel in Frederiksted, St. Croix. Source: Cumulus Clouds – Own work, CC BY 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=2229638.

Local and national environmental groups promptly appealed the permit decision, and their fears about its consequences were soon vindicated. On February 1, 2021, the refinery reopened after nearly a decade closed. Three days later, on February 4, a toxic plume quietly flowed from the refinery’s flare stacks and showered oil droplets on the surrounding neighborhoods.

The official term for these oil droplets is “flare rainout.” According to EPA, inhalation or other contact with flare rainout can cause nausea, skin and eye irritation and hypersensitivity, liver damage, and possible carcinogenic effects. Flare rainout can result in “flaming rain,” which is exactly what it sounds like. As EPA describes it, flaming rain happens when oil droplets ignite in the refinery’s flare stack and “rain down, while on fire, on the facility and neighboring communities.”

“My body wouldn’t work. It felt acidic in my mouth, burned my throat. I started throwing up repeatedly. I thought I was doing to die. You don’t see it, but it gets inside your body. It gets inside you and tears you up from inside.”

One nearby worker reported, “I was working on a roof when I smelled something strange. I suddenly felt weak. My skin scratched. The smell was too strong, it knocked me down. I crawled off the roof, dizzy, stumbling. My body wouldn’t work. It felt acidic in my mouth, burned my throat. I started throwing up repeatedly. I thought I was doing to die. You don’t see it, but it gets inside your body. It gets inside you and tears you up from inside.”

Four flare rainout incidents occurred between February 4 and May 12. On May 12 Limetree Bay suspended operations due to a large fire that emitted dangerous levels of sulfur dioxide, a pollutant that damages the lungs. Two days later EPA used its rarely invoked emergency powers to order Limetree Bay to pause all operations because they posed “an imminent risk to public health.”

In July, the refinery’s owners once again filed for bankruptcy.

In the three brief months that Limetree Bay operated the refinery, flare rainout contaminated hundreds of drinking water cisterns and vegetable gardens. It permeated Frederiksted with a rotten egg smell (caused by hydrogen sulfide, an extremely hazardous gas). Three schools closed because so many teachers and students were nauseous from hydrogen sulfide exposure. The Virgin Islands’ emergency management agency received over 100 complaints from citizens experiencing headaches, sore throats, and nausea, and many residents sought medical attention at the local hospital. Families that lived downwind of the refinery were forced to sleep in their cars upwind.

The impacts of the refinery’s disastrous restart likely won’t become fully clear for decades, as the long-term health effects of residents’ pollution exposure continue to reveal themselves. And Crucians understand they cannot rely on anyone but themselves to conduct the health monitoring that they deserve.

Ms. Gerard and Ms. Sibilly-Brown got together with other community leaders, along with Dr. Bond, and organized a community survey to document the refinery’s continuing impacts. They found that health effects were severe in the predominantly low-income Black and Brown neighborhoods downwind of the refinery. Over 70% of survey respondents reported trouble breathing during Limetree’s episodes, and 66% of respondents reported severe headaches. The survey uncovered three deaths that loved ones attributed to toxic emissions from Limetree. Community members also provided testimonials of health issues that continue to haunt them. One Crucian shared: “[s]ince that time, I’m not okay. My body won’t work. I have trouble standing up, walking. I can’t get my balance. I keep getting sick. My immune system doesn’t work.”

“Since that time, I’m not okay. My body won’t work. I have trouble standing up, walking. I can’t get my balance. I keep getting sick. My immune system doesn’t work.”

The survey found that hundreds of homes were still waiting for their cisterns to be cleaned and hundreds of residents were waiting for medical assistance for respiratory ailment, several months after the refinery closed. Dr. Bond described to me the water crisis that persists through today. Residents’ water cisterns are still lined with petrochemical products, so they must rely on bottled drinking water provided by Limetree. Showering causes rashes.

Early on, Limetree staff went into neighborhoods to investigate the cisterns and cleaned up a few. They quickly realized the scale of the problem and gave up before Limetree filed for bankruptcy. To date, neither Limetree nor the government has conducted a comprehensive investigation into the impacts of the refinery’s restart on residents.

In December 2021, a bankruptcy judge in Texas approved the sale of the refinery to West Indies Petroleum, a Jamaican oil storage company. The new owners intend to restart the refinery yet again. The Biden EPA, with a newfound focus on environmental justice, informed the new owners that they will need to apply for new environmental permits rather than relying on the old permits Trump’s EPA issued. The owners will also need to negotiate a new consent decree with EPA.

Crucians are cautiously optimistic about EPA’s community engagement throughout this process, but they will have to contend with a territorial government eager to restart the refinery as quickly as possible. In April 2021, Virgin Islands governor Albert Bryan Jr. appealed to the White House to speed up the reopening while gas prices are high.