Speaking the Language of Social Responsibility

Patagonia says they’re “in business to save our home planet.” What does that really mean?

Julia Hammond

November 22, 2023

“[I]t is becoming increasingly obvious that a freedom of choice and a delegation of power such as businessmen exercise would hardly be permitted to continue without some assumption of social responsibility.”

In 1953, Howard Bowen published Social Responsibilities of the Businessman—the book that provided the foundation for the movement towards “corporate social responsibility,” which took hold in the US a few decades later. In a sense, Bowen’s book tells it like it is: it acknowledges that corporate activity has a tangible impact on society writ large. It also represents a (barely-implicit) admission that, even in 1953, corporations and their leaders were late to the game: the workers and consumers upon which corporate entities depended for their profits, their power, and their legitimacy had already figured that out.

Corporate leaders could no longer go on pretending that the accumulation of profits served the “greater good” of humanity. If big businesses wanted to maintain the legitimacy of the system that allowed them to accumulate near-unlimited money and influence, they’d have to shape up. The profit-making could continue, but it had to be accompanied by “giving back” some small portion of what they had extracted.

Bowen’s baseline assumption was that social responsibility “ha[d] meaning only in relation to the goals or values which we seek from our economic system.”

the language of corporate social responsibility is everywhere. And it is language first and foremost.

Seventy years after the publication of Social Responsibilities of the Businessman, the language of corporate social responsibility is everywhere. And it is language first and foremost. The concept of corporate social responsibility was created by profit interests for profit interests. It was not for the factory workers, or the environment, or the benefit of anyone to whom the “social responsibility” efforts were directed. It was, and is, a mechanism by which large corporations maintain their legitimacy as the centerpiece of American society.

Corporate Social Responsibility and Greenwashing

The sheer size of some of these companies makes it difficult to grasp their true impact, and equally difficult to figure out which ones are doing relatively less harm. And the language of corporate social responsibility allows companies to play to our sympathies; many corporations seamlessly integrate sustainability, equity, and environmental-friendliness into their marketing materials.

In 2018, Starbucks banned plastic straws, replacing straw lids with (thicker, heavier) plastic lids that work without a straw. Meanwhile, six billion of its disposable cups (which are not recyclable or compostable) end up in landfills every year. In 2008, Starbucks promised to make 100% of its cups reusable or recyclable by 2015. (It hasn’t succeeded.) Even if Starbucks had succeeded in improving reusability and recyclability, it would still be worth noting that their (and many other companies’) “eco-friendly” initiatives focus only on the wastefulness that customers can see and get angry about–reducing plastic waste–and not on the less-visible but often more critical impact of greenhouse gas emissions.

The bottled water conglomerate BlueTriton chooses names for its bottled-water brands (like Pure Life, Poland Spring, Zephyrhills, Deer Park, and many others) that are reminiscent of nature and wildlife. It decks their plastic bottles out in blue and green; on its website, it advertises its “sustainability” commitments against a backdrop of pine trees. The company’s April 2021 rebrand was meant to “reflect [BlueTriton’s] role as a guardian of sustainable resources and a provider of fresh water.” Meanwhile, BlueTriton sends hundreds of millions of pounds of plastic to U.S. landfills each year (though it tells consumers that their recyclable bottles “keep plastic out of landfills”). The company also has a history of draining aquifers to get the water that it sells, and has been caught extracting water from national forests without authorization.

More than just telling customers that they’re “going green,” Patagonia’s messaging boldly goes beyond what most other companies are willing to say: “we can prioritize purpose over profit.”

Oil and gas giant Chevron is fighting a (steep) uphill battle when it comes to convincing consumers that it is “protecting the environment,” but that hasn’t stopped it from advertising that it’s committed to a “lower-carbon future.” Needless to say, the company is lying: it name-drops the Paris climate agreement without actually making any commitment to align its activities with the Paris goals.

Companies that engage in “greenwashing” market their products or brands to consumers who care about the environment without meaningfully improving the business’s environmental impact. We see the hallmarks of greenwashing everywhere: companies make vague promises, use meaningless terms like “eco-friendly” and “natural,” avoid setting numerical goals, and push the idea that saving the environment requires a “collective approach”—“all of us” acting together.

This strategy is extremely effective, in part because it shifts responsibility from the corporation to the consumer. The companies themselves tell us that we are supposed to care about our personal “carbon footprint.” We’re expected to “shop sustainable.” (We are all responsible for recycling those plastic water bottles.) And, of course, buying the companies’ products will help us achieve the expectations that have been set for us. Greenwashing allows big companies to leverage the language of corporate social responsibility while failing to take any action that might be characterized as “socially responsible.”

Patagonia and Corporate Social Responsibility

Patagonia, a company that has been making outdoor clothing and hiking gear since 1973, is undoubtedly pushing the limits of this conversation. More than just telling customers that they’re “going green,” Patagonia’s messaging boldly goes beyond what most other companies are willing to say: “we can prioritize purpose over profit.” The company’s mission, it says, is to utilize business to protect nature. It highlights Indigenous climate advocacy and embraces the language of decolonization. It recommends that customers keep their Patagonia clothes for longer, make repairs rather than buying new products when possible, and trade in their used gear rather than throwing it away. On the company’s website, you can “take action” by signing petitions asking political leaders to commit to environmental justice.

In 2011, the company published an ad in the New York Times that featured a picture of one of Patagonia’s bestselling winter jackets. In bold writing across the page, the ad read “Don’t Buy This Jacket.” The company touted this as an effort to raise awareness about overconsumption and encourage consumers not to buy more than they need.

Most recently, the company has expanded into selling fish, meat, beer and natural wine and promotes regenerative organic farming–because “if we really want to protect our planet, it starts with food.” Patagonia Provisions was founded to expose the elements of the food industry that are contributing to climate change and other environmental problems. It makes food products that “showcase” sustainable production options. When it uncovered human trafficking practices in its Taiwan textile mills, it led an effort to reform the standards in the mills. Its website is not just a place where it sells clothes, but a genuine educational tool.

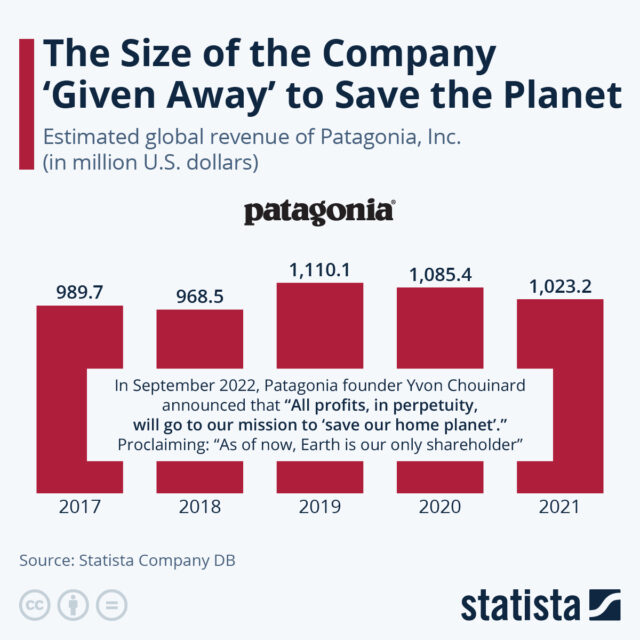

Perhaps for these reasons, Patagonia is widely regarded in the business world as a bastion of responsible capitalism. There is an apparent consensus that Patagonia is “a cut above”—really putting its money where its mouth is. In a Tweet early this year, Rhode Island Senator Sheldon Whitehouse shared that, in his opinion, if a corporation isn’t “Patagonia or Ben & Jerry’s,” it’s “greenwashing.”