Looking back, Will describes the process of trying to find an employer in the public sector who was willing to sponsor him as “really, really, really a struggle.” Although he had hoped to continue working with his 2L employer post-graduation, those hopes quickly evaporated. Sponsoring his H-1B, Will learned, was simply not something that his organization was willing or realistically able to do.

Still, Will remained committed to his dream of practicing public interest law here in the United States. “I contacted a bunch of organizations that focused on immigrants’ rights, not just in Boston, but also in New York, in San Francisco, in LA – a lot of different organizations.” And yet, Will found that his non-citizen status was more of an obstacle than he could have ever predicted. “I was really struggling to find a sponsor[ing] employer,” Will reflects. “[T]he moment I told them I needed some sort of visa sponsorship, that’s when […] the entire process kind of stopped.”

One particular experience has stayed with him even all these years later. After applying to work for a small public interest firm in Syracuse, Will learned that he had been given an interview – a good sign that they were genuinely considering him for the position. Just a few days before the interview, the managing director reached out to Will and asked if he would be needing sponsorship to work in the country. Will responded that he did.

“Literally an hour later, the managing director got back to me, saying, ‘We don’t do that. Unfortunately, we’re not able to move forward with the process.’” And that was that.

At the end of it all, despite his best efforts, not a single employer Will applied to was willing or able to sponsor him for H-1B. He was ultimately able to avoid having to leave the country by enrolling in a master’s program.

If the H-1B is such a common option for international students, why were Will’s experiences so difficult? Although the H-1B system appears to be neutral on its face – the general requirements apply broadly to all “specialty occupations” and, with some exceptions, do not distinguish between specific fields or sectors – not all types of employers are equally able to take advantage. As the Bernard Koteen Office of Public Interest (OPIA) at Harvard Law School comments on its website, “Applicants [that require H-1B sponsorship] run into significant obstacles trying to obtain postgraduate public interest positions in the US.” Due to a variety of employer-side factors, public interest employers tend to have far less bandwidth to sponsor (and thus extend opportunities to) international law students than their private sector Big Law counterparts.

“The moment I told them I needed some sort of visa sponsorship, that’s when . . . the entire process kind of stopped.”

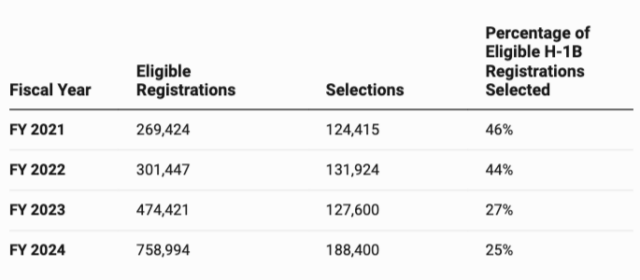

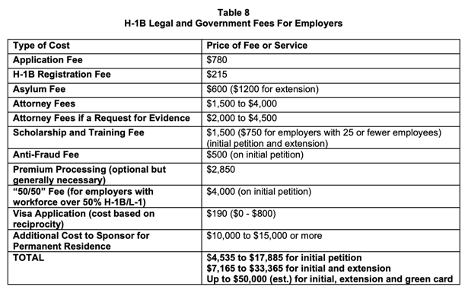

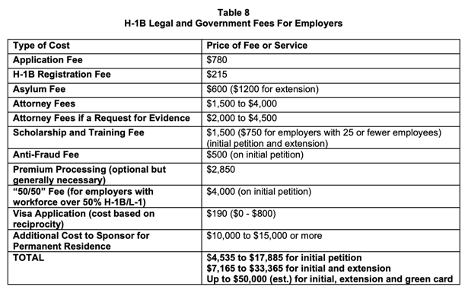

For one, hiring and retaining foreign law students can be extremely costly to employers. The initial petition process alone entails a $780 application fee and $215 H-1B lottery registration fee. Other expenses are required at other steps in the process, including administrative processing fees and fees to support the US immigration system. Significant additional costs may be incurred if the employer lacks experience with the H-1B system and needs to hire an outside immigration attorney for assistance. Even if an employee is granted an H-1B, employers will later have to pay to extend the employee’s status upon expiration of the initial three-year visa term.

According to NFAP, in aggregate, legal and government fees for filing an H-1B petition and extension could cost an employer over $33,000. If an employer later elects to sponsor an H-1B employee for permanent residence upon the visa’s expiration, that could run up to $15,000 more.

All employer-based government fees associated with the H-1B sponsorship and extension process in effect as of April 1, 2024. Source: NFAP.

What’s more, recent actions by US Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) suggests that these substantial costs are unlikely to abate. The current fee structure, implemented pursuant to a USCIS final rule published in January 2024, reflects a significant increase in total fees for employer-based H-1B petitions over the former status quo. Although 501(c)(3) nonprofits and small employers are exempted from this rule, many public interest legal employers do not technically fall within this narrow carveout.

The prevailing wage requirement, referenced earlier, also contributes to the H-1B’s financial burden. If the government-determined “prevailing wage” exceeds an employer’s listed “actual wage” for a position, that employer may be required to pay an H-1B employee a higher wage than it would have otherwise paid to a domestic worker. For smaller nonprofit organizations, this is likely to be the case because nonprofit salaries tend to be lower than government salaries, but both sectors fall under and go towards calculating the same “prevailing wage.”

“Th[e] prevailing wage requirement in Boston, for example […] I believe it’s like $90,000,” Will comments. “There’s no PI employer that can guarantee that […] I mean, that may be possible for private employers, but not public interest employers at all.”

In practice, the prevailing wage condition limits the ability and willingness of many nonprofits to pay H-1B lawyers. For the most part, unless an international candidate is truly exceptional and fits a hard-to-fill position, a lower paying nonprofit would rarely consider paying the prevailing wage. Thus, H-1B sponsorship can quickly become an unrealistic option for a public sector employer to consider, much less an attractive one.

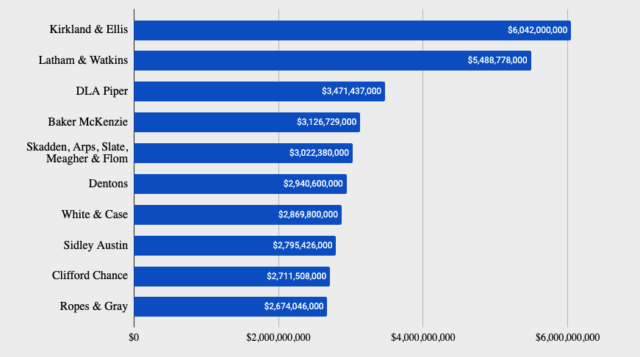

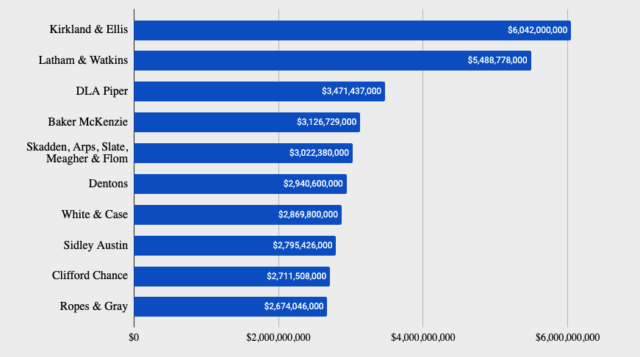

For a Big Law firm that rakes in billions in annual revenue, however, these financial burdens can be absorbed with no major difficulty. In fact, law firms are generally very receptive to sponsoring international candidates for associate positions. In the 2023 Early Interview Program (EIP) recruitment cycle at HLS, when surveyed to indicate willingness to sponsor J.D. candidates for H-1B, 86% of responses by participating Vault 100 firms indicated in the affirmative (with 39% saying “Yes” and 47% “On a case-by-case basis”), a statistic that starkly contrasts with Will’s experiences with employers in the public sector.

“The prevailing wage requirement in Boston, for example. . . . I believe it’s like $90,000,” Will comments. “There’s no PI employer that can guarantee that . . . I mean, that may be possible for private employers, but not public interest employers at all.”

Many Big Law firms do not even require applicants to indicate their sponsorship needs before considering their candidacy. Such was the case with Mark’s recruitment process. “They gave [me] an offer knowing that [I’m] a good candidate, and not whether [I] need[ed] sponsorship,” he recalls. As should arguably be the case for all employers, Big Law appears much more able to prioritize whether an international student is objectively a good fit for the job.

By contrast, many public sector employers such as legal aid organizations or nonprofits rely primarily on government funding, grants, or charitable contributions to survive. For such employers who are non-revenue-generating and constrained by tight budgets, the financial costs of H-1B sponsorship may be prohibitively expensive, or at the very least deeply discouraging.

Anna, an associate director at a California-based nonprofit legal services firm, says that a big part of the thought process for considering whether to sponsor an international candidate is the cost-benefit analysis of it all. In the rare instances where her firm did actually provide sponsorship for a position, Anna observes, it was often the case that “we had held those positions open for so long that we were starting to spend more money on recruitment anyway […] it ends up being [less costly] if we do the H-1B versus hir[ing] a recruiter to help fill those positions.”

The world’s top 10 largest law firms by revenue in fiscal year 2021. Data sourced via ALM. Graphic created on Google Sheets by Max Li.

Closely related to an employer’s financial considerations is its administrative capacity to take on the hassle of the H-1B sponsorship process. “I think [the ability to sponsor is] related to the capacity of the HR team,” says Diane, a recruitment coordinator at a Massachusetts-based legal aid organization. Whereas Big Law firms employ well-staffed, well-resourced, and dedicated recruiting teams, many public interest employers do not.

Indeed, this is one of the reasons why Diane feels that her organization has been able to sponsor international candidates while most others in the public sector have not. “[W]e have an HR director who is only focused on doing HR. We also have me, who’s the recruiting coordinator, and now we recently just hired another HR assistant.” Diane also credits the relatively large size of her organization. “Because we are larger, [with] 160 people in our organization, maybe […] we have a better capacity to do it.”

Anna’s firm is the same. It has more than tripled in size in the last few years, which has allowed it to commit more resources and personnel to its hiring department. “[Nowadays,] one of us finally has [the] capacity to look into [the H-1B option], whereas in the past we were all caught up in a lot more of a programmatic management.”

Those public sector employers without such comprehensive and sophisticated hiring teams may lack not only the bandwidth, but also the experience to properly go down the H-1B road. “[H]istorically, [it] wasn’t really a policy of not [sponsoring],” Anna reflects. “It was just […] not something that we were familiar with.” Hiring an immigration lawyer to help with the process may be possible, as Anna’s firm has done on occasion, but can entail a myriad of other expenses and considerations.

But perhaps the biggest obstacle to sponsorship across public sector employers is the inherent and immense uncertainty of the H-1B process. As Diane points out, “[There’s a] risk in taking on and applying for a visa that might not turn out.”

Most international law students can work in the country for a year following graduation through a temporary form of authorization known as Optional Practical Training (OPT). After that, however, there is always the lingering possibility that an employer might try for H-1B sponsorship – paying all the exorbitant fees and jumping through all the administrative hoops – just for the candidate to lose the lottery, be forced to depart the country, and leave the employer even worse off than it was before.

“For most of our positions . . . we need someone now,” Anna says. “Someone who doesn’t need sponsorship can start right away. Someone who does, we’re going to be waiting several months . . . and we’d be keeping a vacancy open for that many months.”

This uncertainty is a lot easier to tolerate for Big Law firms that have offices spanning the globe, hire hundreds of employees each cycle for general positions, and have considerable capacity to reorganize personnel as needed. Public sector employers lack that sort of flexibility: on top of being much smaller in size, they generally hire one person for one specific role at a time, and if that one person is eventually forced to leave the country only one year after being employed, the employer could be significantly impacted.

“[For] [m]ost of our positions […] we need someone now,” Anna says. “Someone who doesn’t need sponsorship can start right away. Someone who does, we’re going to be waiting several months […] [and we’d] be keeping a vacancy open for that many months.”

Ultimately, as Anna indicates, the process of deciding whether or not to sponsor H-1B is a cost-benefit analysis. For most public sector employers, however, the scales are just too imbalanced from the get-go. Many categorically decline to sponsor. Anna’s firm, for instance, includes a questionnaire in its hiring application that, in most cases, automatically weeds out candidates who indicate that they will need sponsorship in the future. This can lead to an immensely difficult road for international students like Will.

Thus, as OPIA notes, “postgraduate public service employment can be a huge challenge for non-citizens.” Although Big Law firms are certainly not immune to these constraints, they remain far better equipped than public sector employers to navigate the H-1B system and take full advantage of the pool of international talent flowing into law schools across the country.

An H-1B visa. Source: Shutterstock

It’s worth noting, though, that the pressures driving H-1B seeking students away from the public sector and towards Big Law do not stem solely from the employer side. That is, although public sector employers may be reluctant to employ international students, international students are generally not that likely to apply to work with those employers either.

“I think I can count on my hand, maybe, the number of people who […] have said they need visas, and I’ve seen over 1,500 candidates,” Diane recalls. “I would say maybe like one to two percent: it’s a very low percentage.”

Most international students are aware of the constraints on sponsorship employers face, including the fact that these constraints are far more significant in the public sector. This can deeply influence their choice of employer and career. “Even prior to applying,” Mark notes, “international students [tend to] have an idea of which firms to apply to and which firms to not even bother trying, and that […] restricts the pool of firms that you would have access to.”

In the inherently uncertain domain that is the H-1B visa system, international students know that Big Law is by far the easiest path to sponsorship. “International students value that certainty,” Mark says. The public sector is far more of a gamble – one which all too often deters international students from a career in public interest law. “I have a bunch of friends who […] wanted to do PI for law school,” Will recalls, “but [ultimately] did not choose that path because they knew it was so hard for them to get [an] H-1B.”

“I have a bunch of friends who . . . wanted to do PI for law school . . . but did not choose that path because they knew it was so hard for them to get an H-1B.”

Law students do not have infinite time and resources. They cannot (or, at least, should not) haphazardly apply to every single employer they come across. The deliberation of which career paths and employers to pursue is a strategic one, and the stakes are even higher for international students who risk being forced to leave the country if they cannot secure H-1B-sponsored employment. Understandably so, many are deeply hesitant to go through the trouble of applying for a position just to be summarily disqualified for their noncitizen status.

![scales - Logo for The [F]law](https://theflaw.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/flaw_scale_divider.png)

Compared to massive corporate actors in other industries that, in recent years, have resorted to deliberate and even fraudulent measures to game the H-1B system to their advantage, Big Law’s role in all this appears to be much more passive. Big Law has exerted no meaningful influence over USCIS’s fee structures and filing requirements, nor over the workings of the H-1B lottery. Indeed, it seems to be the case that Big Law firms, simply as a result of their financial resources and administrative capabilities, just so happen to gain the most from the present status quo. But that is not to say that Big Law is innocent in all this.

“The big corporate firms are the ones that are sending hundreds of applications in at a time and filling up all the slots,” Yliana laments. “[M]ost of the small orgs and small applicants have very little chance of [winning the lottery].”

As is generally the case in the corporate domain, resources create power, and here, the immense imbalance of resources across actors in the H-1B ecosphere creates an immense imbalance of power. And so, intentional or not, Big Law’s actions leave noncorporate actors severely disadvantaged in the process.

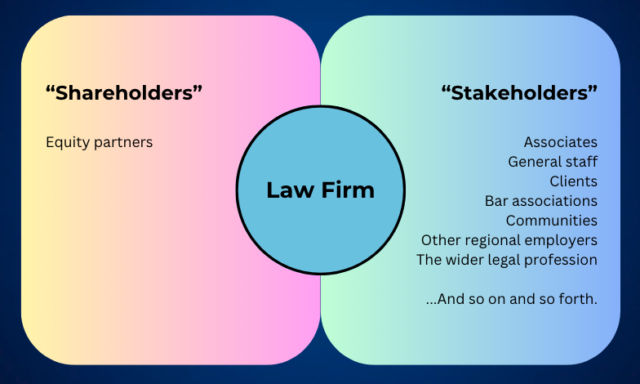

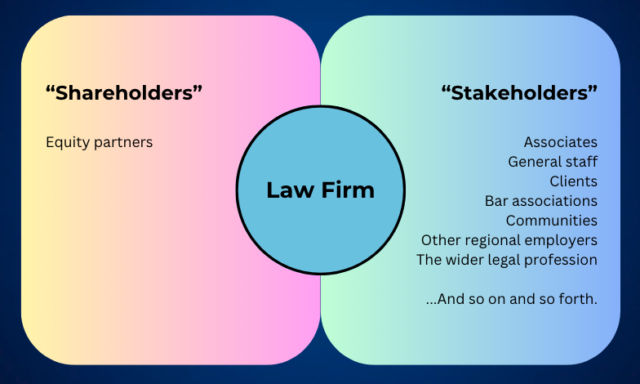

Can we expect Big Law firms to recognize its disproportionate power and take steps to help create a more equitable H-1B landscape? Probably not. Under the dominant theory of shareholder primacy, a corporation’s top priority is maximizing value for its shareholders – in the context of a law firm, the equity partners. If we accept this view, law firms should not take it upon themselves to try to rectify social inequalities or make socially beneficial decisions. Not only do they lack the expertise, but misguided attempts could open the floodgates to undisciplined governance. Whether the H-1B system is inherently inequitable and what can be done about it may be meaningful questions, but not ones which Big Law firms should concern themselves with addressing. If the H-1B system should be changed, responsibility to do so should fall on the government and it alone.

“The big corporate firms are the ones that are sending hundreds of applications in at a time and filling up all the slots. Most of the small orgs and small applicants have very little chance of winning the lottery.”

And yet, the competing theory of stakeholderism, wherein a corporation bears responsibility for all of its stakeholders, rejects this. If we imagine a law firm’s stakeholders to include not only the international students who apply for positions with the firm, but also the public sector employers with which the firm shares the collective legal profession, then Big Law may bear some responsibility for pitching in to ensure their just treatment under the H-1B visa system.

In recent years, this notion that Big Law firms may have responsibilities beyond simply profit creation has already started to take root, particularly with respect to ESG and DE&I. As such, firms may not be averse to taking steps towards solving the H-1B problem in the future. This could include providing charitable grants to public interest employers – subsidizing their capacity to sponsor international candidates for H-1B – or offering pro bono legal services to help guide them through the procedural complexities of the sponsorship process.

How the corporate governance of a law firm might be imagined through the competing lenses of shareholder primacy and stakeholderism. Graphic created on Canva by Max Li.

The disparate impact of the H-1B visa system serves as a stark reminder that even well-intentioned, facially neutral government programs may inadvertently strengthen corporate power at the expense of noncorporate actors. So long as these discrepancies exist, public interest employers will continue to struggle to take in talented international students through the H-1B system, while international students will continue to be pushed towards Big Law for its relative certainty and assurances.

It may be unclear what sort of substantive changes to the existing H-1B structure are plausible or even desirable, but it is abundantly clear that improvements to address this problem are long overdue.

Will feels strongly that the prevailing wage system needs to be adjusted to reflect a more realistic expectation of what the public sector can pay their employees. Specifically, he advocates stratifying the prevailing wage schedules so as to keep public interest positions in their own category, separate from government or private sector attorneys, so as to bring the prevailing wage and actual wage closer together for public sector employers. “[T]here’s a huge gap [and] I think the prevailing wage chart must take that into account,” Will remarks.

Additionally, the government can consider providing to public interest employers subsidies earmarked for facilitating sponsorship needs as they arise. Such support would lower the financial barriers that constrain the public sector from considering the H-1B as a realistic option. To that end, USCIS could also just lower the glaringly high costs of filing an H-1B petition. However, because USCIS did raise these costs with the express purpose of combatting a growing trend of frivolous and fraudulent H-1B applications, this is admittedly unlikely to occur.

International students like Mark and Will are not rare in the slightest. By all accounts, the prospect of practicing law in the United States appears to be increasingly attractive to foreign students: over the last decade, the percentage of international students enrolled in J.D. programs in the US has nearly doubled. Still, noncitizens accounted for just 3.3% of JD candidates nationwide in 2019. That is to say, international students still very much remain a minority group across the greater legal profession.

As it exists today, the H-1B visa system exerts immense influence on the capacity of international law students to decide their futures and navigate their careers. Many of the issues uniquely faced by these students often slip under the radar, regrettably unbeknownst to the grand consciousness of a profession overwhelmingly represented by US citizens. If we wish to foster a profession grounded in inclusivity and parity across its practitioners, a comprehensive reimagining of the H-1B visa system may be inevitable.

![]()