How do we go from a world where helping people is cliché to a world where swaths of lawyers are fighting to defend those doing just the opposite? The people who write that they want to help people too much on their applications are the same people three years later working for firms actively fighting for those who have hurt people. Intuitively, one might assume that the answer lies in money; the more money a corporation has, the more money a lawyer can make defending them. Most people know going into law school they can make more money if they go to work for a big law firm, but it runs much deeper than that. Big law firms are essentially buying new lawyers from the moment they step on campus as first year law students.

Every day, I walk by classrooms with plaques on the side that read “Mayer Brown Classroom” and “Vinson and Elkins Classroom,” named for two big law firms that apparently sponsor the rooms where we have lectures. In between classes, law firms often host lunches to talk about their offices and offer opportunities to network. Last year many of the lunch events with big law firms were on Zoom, but they still sent us $25-30 GrubHub or UberEats vouchers for signing up. Once, I lucked out by still getting a gift card when I forgot to attend the event.

Image provided by A Mis 30 por Boston

If you opt out of the law firm lunch events, you can usually still get a free lunch most days of the week sponsored by student organizations who are in turn sponsored by big law firms. Last year, people would post in group chats about when Texas Club was having a free lunch event, and we would all show up and make jokes about our lack of ties to Texas, just attending to fill up heaping plates from the barbecue platters. Despite the jokes, it didn’t really matter that we had no ties to Texas. Texas is a hub for big law. Big law firms want people to come to Texas, and they can pay for it with a pulled pork platter from Smokeshop BBQ in Harvard Square. Once when one of my friends and I were eating the leftovers from a lunch event in the dorm lounge last year, an upperclassman even offered to take us out on the firm’s dime for dinner at a restaurant of our choosing if he could talk to us about the firm.

In Harvard Immigration Project (HIP), a student group I was in last year that does pro bono work for immigrants through projects such as working on international policy and providing free legal services to immigrants in the Boston area, many of our events had free lunch. At one point, we had a mandatory free lunch where representatives from big law firms Zoomed in to speak. The crux of the event was to talk to us about how we can go into big law and still volunteer our hours to help people with free pro bono services. In bold in our HIP newsletter, it was stressed that this was “the only mandatory HIP event all year” and it was “mandatory for all HIP members in order to support our ongoing fundraising efforts.” I was never able to schedule a meeting with a client because of class conflicts, but I had to go to that lunch. Immigrants in Boston who need free legal services can’t pay a student organization what it needs to function for an academic school year, but a big law firm can.

After school, there are the bars. Many events at bars are explicitly labeled as networking events where firms come and buy people free drinks and talk to them about their work. One student provided a humorous anecdote that paints a picture of such events in an email announcing an event at Grafton Street, a pub in Harvard Square: “The first time I ever went to an event at Grafton was an open bar firm reception during 1L. I saw someone walk up to the bar and say to the bartender ‘What is your most expensive scotch? I’ll take a double.’ And honestly, that is the energy we should all be trying to bring into finals szn. So this week, we’re heading to our favorite bougie “Irish Pub” this side of Mass Ave.”

Immigrants in Boston who need free legal services can’t pay a student organization what it needs to function for an academic school year, but a big law firm can.

Sometimes firm sponsorship of drinking events is not immediately apparent. For example, the email above was for “bar review” a weekly event where a student-run organization called Harvard Law Central (HLC) rents out a bar in Cambridge or the Boston area just for Harvard Law students. It’s a pretty key part of the social experience at Harvard Law School, especially as a first-year student, or 1L. It’s held every Thursday, entrance is free unless it’s for a special event like the winter formal or boat cruise, and there’s often free food or free drink tickets. Sometimes, when they’re handing out wristbands to the events, they even hand out free t-shirts. The big law firm logos plastered on the backs of the shirts make clear who is picking up the bill for these events. Last year’s sponsors that got a place on the shirts were Felipe’s (my favorite bar in Cambridge, known for their rooftop frozen margaritas and Mexican food), Hong Kong (a Chinese restaurant, colloquially shortened to Kong, that turns into a karaoke bar between the hours of 8pm and 2am and the venue for both the first bar review I went to the Thursday after I turned 21 and the most recent bar review I went to a few weeks ago), Morgan Lewis, Paul Weiss, Simpson Thacher, Weil, Debevoise & Plimpton, Davis Polk, Hogan Lovells, Dovel Luner, and Paul Hastings (all law firms). This year’s shirt has some of the same firms but also saw some changes; interestingly, Mayer Brown, the lecture hall sponsor mentioned above, now sponsors social activities as well as classrooms. When I wear mine around campus, I feel like a walking billboard advertisement for corporate law.

Harvard Square, featuring Hong Kong and Grafton Street (to Hong Kong’s left), two venues for bar reviews and other social and networking events for Harvard Law students.

Image provided by Flickr

In their limited free time, many, if not most, students at Harvard Law School join student-run journals. Journals are essentially compilations of the writings of legal scholars, put together and edited by law students. For the average 1L, being involved in a journal looks like showing up to “subcites” a few Saturdays a semester and working on fact checking and formatting. The journals have different issue areas; for example, there’s a Harvard Journal of Sports and Entertainment Law, a Harvard Human Rights Journal, and a Harvard Journal of Law and Gender. There’s a conservative journal and a liberal journal. There are also journals that are more valued by corporations and those that are not so much.

I was involved with Harvard Environmental Law Review last year. At one of our spring subcites last year, we got a text from someone at a journal that does more business-related work asking if we wanted to come up to the student organization room to get their leftovers from breakfast. The whole room was filled with platters of eggs, bacon, sausage, bagels, donuts, pancakes, etcetera. These were their leftovers. They needed our help clearing them out before the lunch and the sheet cake they ordered arrived. The last free food we saw at an Environmental Law Review subcite had been a few bags of bagels at the first one. I have learned that environmental work is not one of the most compelling receptacles for corporate funding.

At the end of our Legal Research and Writing class, 1Ls are required to do a mock argument in front of a judge based on a legal brief we were assigned with a partner for a pretend lawsuit appeal. The legal brief is arguably the biggest assignment for 1L law students, the culmination of our first year of education on legal research. The oral argument is the mandatory follow-up assignment that everyone must attend to compete with their partners in a mock debate. At the oral argument, there is a reception with hors d’oeuvres and, characteristic of many Harvard Law School events, an open bar. We were told about the reception before the event, but when my Ames partner and I walked in, I was surprised to discover that our oral argument reception was actually a networking mixer with a big law firm. I was immediately swept into a conversation with a lawyer about her work at the firm. Before leaving the event, we were directed to free merchandise to take with us; law students can now sip out of their Wilke water bottles months later in memory of the big law networking event that stood as the celebration of our first year of learning how to conduct legal research.

So, our classrooms, our meals, our social lives, and our extracurricular activities are largely funded by big law firms who make it explicitly clear that they are sponsoring these activities and will sponsor the ones they approve of more. However, that doesn’t mean we have to choose to go work for the firms that are paying for all of these things. Just because my new favorite oversized t-shirt says “Paul Weiss” on it and my seminar is next to “Vinson and Elkins classroom” doesn’t mean I have to go work for them. I can enjoy my complementary Felipe’s margarita and keep deleting OCS emails until I get a job in environmental law. There are no ties attached to the free meals and the wine and cheese at oral argument receptions. My earlier claim that big law firms are “buying” us might be slightly extreme, seeing as they aren’t really “buying” anything; they’re just pouring their money out and, hypothetically, potentially getting nothing in return. However, there must be a reason they are so willing to let hundreds of Harvard Law Students wine and dine on their dime every year.

Our classrooms, our meals, our social lives, and our extracurricular activities are largely funded by big law firms

The legal world isn’t the only field where entities with money spend their dollars on professional advocates with no guaranteed and visible strings attached. When big drug companies want to sell more of their concoctions, their conduits are doctors. In his 2021 book Empire of Pain, Patrick Radden Keefe included a poignant quote painting a picture of the phenomenon, writing, “The doctor is feted and courted by the drug companies with the ardor of a spring love affair… The industry covets his soul and his prescription pad because he is in a unique economic position; he tells the consumer what to buy.” He goes on to include instances of drug companies giving free stethoscopes and textbooks to medical students and Pfizer sponsoring a golf tournament with their logo on the golf balls. One study found that industry spent a total of $3.4 billion on physicians and teaching hospitals in a five month period. 80% of those payments come in the form of meals. Many drug companies pay doctors to speak about their products at dinners that other physicians are invited to. Much like big law firms in the legal industry, big corporations have invested countless dollars in academia, social events, and food in the medical field.

However, that doesn’t mean the physicians who pharmaceutical companies are throwing money at have to sell those companies’ products. No one who used one of Eli Lilly’s stethoscopes in medical school has to sell Prozac, and, theoretically, doctors can enjoy a nice dinner on Purdue Pharma and never prescribe a single one of their products. As a senior assistant general counsel at the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America put it to a journalist at CBS, “A modest meal is not going to affect the independence of the health care practitioner.” One doctor who speaks for a pharmaceutical company at events reacted to the idea that he himself or other doctors’ prescribing habits could be influenced by these efforts of big pharma, saying, “Absolutely not. The physicians who are in the audience may notice it if they have been educated to that drug and the benefits of that drug — they may see an increase in writing. But specifically in my own? I don’t believe so.”

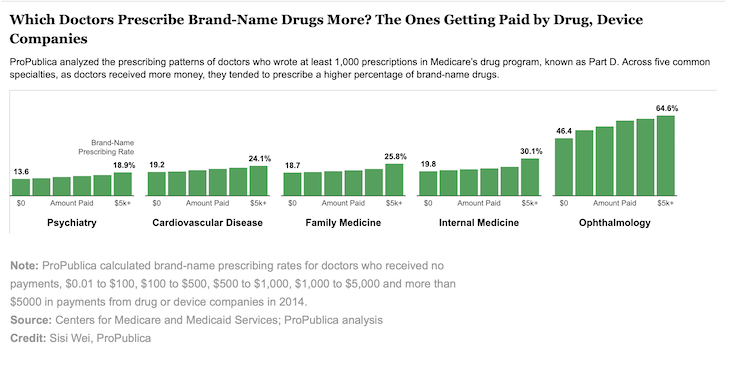

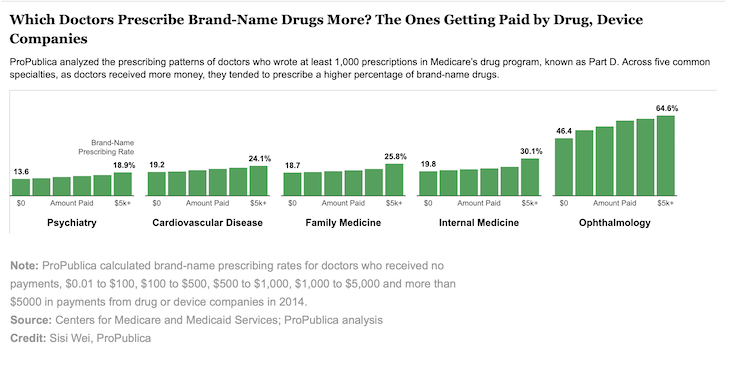

However, the general counsel and the doctor are wrong. The previously mentioned study found that even after pharmaceutical company sponsored lunches of less than $20, doctors are statistically more likely to prescribe brand-name drugs. One sales representative for a major drug company reported that, after paying a doctor $1,500 to speak at an event, that doctor will prescribe an additional $100,000 to $200,000 worth of their drugs. A ProPublica study compiled some of its results in the chart below.

Graph provided by ProPublica

The point of this extended metaphor is that money from big corporations really can make an impact on professionals, even when it logically shouldn’t. Getting free meals and the flattery of being asked to speak at an event shouldn’t make doctors actually prescribe different medicines to their patients; that is clearly completely unethical. But it does. If a practicing medical health professional can be bought by a sub-$20 meal, why can’t a law student be bought with a countless number of free meals, alcohol, t-shirts, classrooms, etcetera?

Researchers can’t do a completely analogous study on law students, comparing the professional choices of those who have and have not taken money from law firms because we’ve all taken money from law firms. I would have a prohibitively difficult time even beginning to quantify the money I personally have taken from firms in just my first year and a half at law school. That being said, we do have statistics about what people want before law school and what they want after law school after invariably being thrown at least some big law money. Research shows that over 50% of law students who come into law school saying they want to work in public interest leave with jobs in big law. Robert Granfield found that, at Harvard, 70% of incoming law students expressed public interest aspirations but only 2% of 3L law students planned to leave with public interest jobs. The space between the two is pumped with money from big law firms in the form of cocktails, free pizza, and embossed water bottles.

70% of incoming law students expressed public interest aspirations but only 2% of 3L law students planned to leave with public interest jobs.

Working for a big law firm doesn’t necessarily mean you are going to be fighting the Erin Brokoviches of the world and defending people who are destroying peoples’ lives. At least from what I have observed or heard second hand in my limited time in law school, much of the work at a law firm is fairly run-of-the-mill: contract disputes, arguments over which corporation is paying for an environmental issue, compliance work, and other things a firm lawyer I once spoke with in an informational interview described as “amoral.” However, of course, there are those lawyers who are “bought” by their law firms and then stay there to do the cases and represent the clients that, to put it euphemistically, most of the law school applicants who wanted to “help people” would never think of when writing their personal statements and dreaming of why they want to go into the law.

“You’re just a lawyer.”

I talked to a couple big law firm partners who argued some of the most major environmental justice cases that have come out in recent years (if you are sensing a theme, yes, I am interested in environmental law) on the side in opposition to the environmental justice advocates. Based on our conversations and what I have heard just by virtue of being in law school for a year and a half, the general justification for advocating for wealthy clients whose interests are what most people (including sometimes the lawyers) see as inherently wrong is that “you’re just a lawyer.” Your “job… is to point out uncertainty rather than certainty” with an “obligation to zealously represent your client” even if you don’t “perfectly align” with them. This is the “system” that they “bought into.” To paraphrase, this is the world we live in, and if someone is going to defend the bad guy and make a lot of money (tangentially, they may not be the bad guy, but it’s not really your job as the lawyer to find out, so it doesn’t matter anyway), why not do it yourself?

To some degree, they’re right. Someone is going to defend the corporation that gives people cancer, and it’s hard to prove that they really did give someone cancer, and as they pointed out, even in public interest law you may not always completely agree with the clients that you are advocating for even though, at the end of the day, it is still your job to advocate for them. For example, even when lawyers don’t think a client they have taken is going to be successful in pursuing a given strategy and rightfully say as much to their client, they ultimately must do what the client wants. However, there’s clearly a difference between asking for more money or taking a case to court instead of settling when you don’t think it’s a smart move and taking your repeat corporate client’s case after they caused deaths in a vulnerable community. The space between is often blurred and difficult to navigate. In the legal world there are many questions you have to ask yourself: How much do you want or need your values to align with the organization or law firm that employs you? If your values don’t align with your employers’, when do you say no to the cases they assign you? How certain do the facts have to be for you to decline a case? To what extent do you consider your role in the system as a whole and how society at large and the legal system are already helping or disadvantaging the client you have taken? How far will you go in “vigorously advocat[ing] for your client, even when, and especially when, you disagree with them?

Image provided by Pexels

I also spoke with a Harvard Law School graduate starting out at a big law firm who mentioned a “red line” out there for him that he wouldn’t morally go past in deciding what cases to take but admitted he didn’t know where that was yet. At one point, I asked one of the partners I spoke to about wanting to be on the opposite side of some of the cases she argued and if she would have been on that opposite side had she stuck with her original goal of going into public interest after law school. She said it was hard to tell when she would have been arguing against some of the corporations she advocated for in her current job because she hadn’t really picked out a sector of public interest that she wanted to be involved in, and there are always going to be competing interests on the other side of a case. The other partner I spoke to said that “the facts aren’t always your friends,” but rather, “uncertainty is the friend of the defense council.”

There is a slippery and often morally confusing track between typing up a personal statement about being a voice for good in the world and either living that into fruition or taking a case in which you are just the opposite.

“Uncertainty is the friend of the defense council.”

If you’re not really sure where your red line is, you don’t really know what side you want to be on, and you relish uncertainty, how many free lunches, how many free margaritas, how many soft t-shirts and all you can eat breakfast buffets, how many salary raises, promotions, bonuses, and wins will it take to move your red line just a little further, inch by inch, until you go from avoiding saying that you want to help people because it’s cliché to avoiding saying that you want to help people because you’ve forgotten what helping people even really means?

![[F]law School Episode 8: Selling Harvard Law Students](https://theflaw.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/Screenshot-2024-09-08-at-9.59.54 AM-640x427.png)