Welcome to Miami’s Housing Crisis

How Corporations Use Housing Laws to Serve Shareholders

Sofia Scotti

November 24, 2024

It was November of 2023 when Leo de Paz was told by his landlord that he needed to find a new place to live. “After 15 years of living here,” he told his landlord in his shock and dismay, “you can’t just ask me to give you the house in one month.” With the holidays quickly approaching and two young children to take care of, he felt that this timeline was completely unfeasible and asked if he could have at least until February. The landlord however, remained firm. He would grant him an extension until January 15th but no longer than that.

The landlord told him that he was looking to downsize. That he was going to sell his own home to move back to the property that de Paz was living in with his husband and two kids. De Paz however, had other suspicions.

After living in the Coral Gables area of Miami for the better part of two decades, he had watched as the rent for the properties around him became more expensive while his own rent had remained well below market value. He suspected that the landlord had realized that he could be making a much bigger profit on this property and was pushing him out so that he could make repairs and rent it out to new tenants who could pay a higher price.

De Paz’s neighborhood had undergone a transformation in the last 15 years. Whereas once working-class people could comfortably afford to live and support their children on two incomes there, today, it has become impossible.

De Paz’s situation is not an isolated one nor is it only happening in one neighborhood. Throughout Miami, people are increasingly finding that the homes that they grew up in and have lived in for decades have simply become unaffordable. This has left thousands of people with a choice. Either pay obscene amounts for your rent or move away from your home and find somewhere else to live.

“After 15 years of living here…you can’t just ask me to give you the house in one month.”

Indeed, the median asking rent in Miami increased 27% since 2019 and by June 2023, Miami’s metropolitan area was ranked as the 2nd most expensive area to rent in America. This is especially significant since Miami’s mean hourly wage is $28.36 which is 5% lower than the national average. For comparison, New York City, which was the most expensive city in America in 2023, has a mean hourly wage of $37.77. As a result, between 2020 and 2022, Miami lost 79,535 people to other parts of Florida and other states. Though this population loss was offset slightly by out of state immigration into Miami, this is still the first time since the 1970s that Miami has experienced a population loss.

“After 15 years of living here…you can’t just ask me to give you the house in one month.”

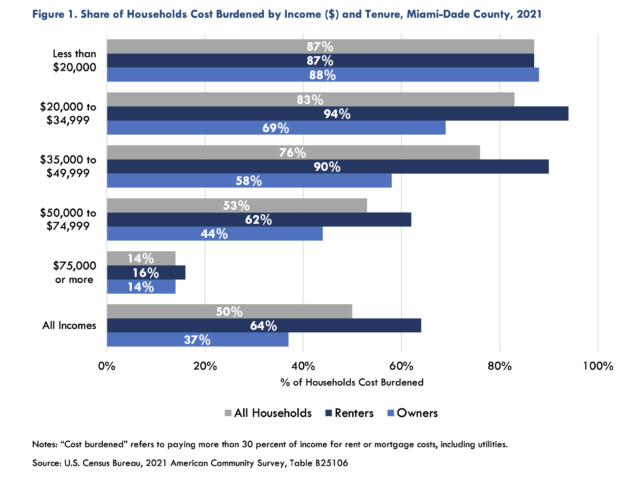

According to the Shimberg Center for Housing Studies’ Miami-Dade County Housing Needs Assessment, most households making less than $75,000 a year in Miami-Dade were “cost-burdened” meaning that they paid more than 30% of their income for their housing. Black and Latino households, moreover, are significantly more likely to be cost-burdened because they are more likely to be renters than their white peers. The report additionally determined that if low-income individuals are to be able to afford to stay in Miami, 90,181 affordable units need to be added to the rental market to alleviate the pressure.

After a significant push from grassroots organizing groups, Miami-Dade County’s Mayor Daniella Levine Cava declared an affordable housing crisis in April of 2022.

Source: Miami-Dade County Housing Needs Assessment, Page 3

When asked about the reasons behind the rising housing costs in Miami, Alana Greer, a Miami movement lawyer and the director and co-founder of Community Justice Project says, “it’s not that complicated, it’s corporate greed for the most part.” Though there are increasing costs associated with housing because of climate vulnerability, insurance costs, property taxes, and the market getting more competitive, Greer believes that those factors are very small compared to the efforts of large corporate developers and landlords to get every last cent they can out of each building by charging exorbitant rents and pushing local people out to make way for higher income individuals. And these corporations are allowed to do so because the laws in Miami prioritize the interests of shareholders over those of community members.

“It’s not that complicated, it’s corporate greed for the most part.”

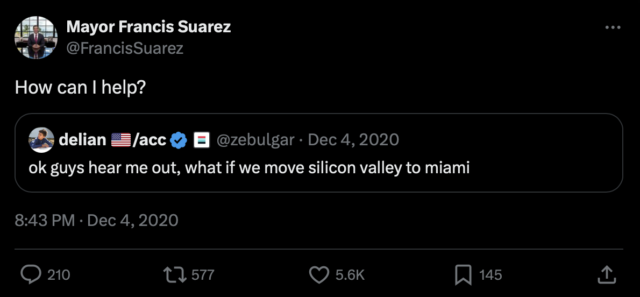

It is difficult to overstate the power that corporate developers and the real estate industry have over the politics of Miami and of Florida as a whole. Because Miami is a relatively new city, much of it was built by large corporate developers and their footprint on the city is palpable. There are schools, roads, and malls named after developers like Arvida Corporation, a prosperous Florida real estate developer acquired by Disney in the 1980s, and George Edgar Merrick, the real-estate developer who founded the city of Coral Gables. So, when it comes to policy surrounding affordable housing, much of it is deeply affected by the desires of corporations and very few initiatives can get passed without their support.

According to one report which looked at campaign contributions to Governor Ron DeSantis, the Republican Party of Florida, the Florida Republican Senatorial Campaign Committee, and the Florida House Republican Campaign Committee, between January 1, 2019 and July 31, 2022 Republican leaders received over $90 million in campaign contributions from developers, the real estate industry and related interests. The biggest of these contributors, donating $3.1 million, was Florida Realtors, a lobbying group whose “mission is to advance Florida’s real estate industry by shaping public policy on real property issues.” Moreover, during the 2022 election cycle , the real estate industry was among Governor DeSantis’ largest donor base, donating over $7 million.

“It’s not that complicated, it’s corporate greed for the most part.”

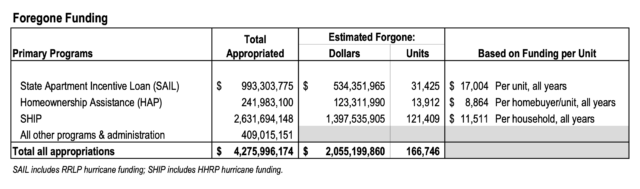

And while Florida has ensured that corporations and their shareholders are allowed to profit off development, they have deprioritized the interests of low-income community members. In fact, the Florida legislature routinely siphoned funds from the Sadowski Housing Trust, a trust meant to fund affordable housing projects, into general revenue spending over the course of two decades. Altogether, they reappropriated over $2 billion which the Florida Housing Finance Corporation estimates could have led to the construction of 166,746 affordable units.

Source: Florida Housing Finance Corporation

Alongside its divestment from affordable housing projects, Florida has also worked to make it extremely difficult for municipalities to require any affordability in new development. For example, in 2018, Miami passed its first ever mandatory inclusionary zoning ordinance. Mandatory inclusionary zoning is contrasted with voluntary inclusionary zoning in that the former requires developers to set aside units in their buildings for low-income individuals while the latter merely incentivizes it with things like density bonuses and tax breaks. But the very next year, with the support of lobbyists from associations like the Florida Home Builders Association, which advocates for the interests of the homebuilding industry, Florida’s House passed a law that preempted any mandatory inclusionary zoning that did not provide cost offsets to the developer.

Florida has also used preemption to ensure that corporate landlords are protected from rent control. In 1974, Miami Beach imposed rent control in their city to mitigate the effects of a housing emergency. Corporate landlords in the area were angered by this and challenged the ordinance. The legislature then got involved and passed a law that made it extremely difficult for cities to pass rent control measures. According to Greer, this law made it so that in order to get any sort of rent control, cities needed to declare a special kind of housing emergency, put the measure on the ballot and, if they happened to win, repeat the process every year.

Since then, very few cities have even tried to implement rent control and when they have, they have been met with strong opposition from corporate interests. In 2022 for example, Orange County attempted to pass a rent stabilization ordinance, but were very quickly sued by Florida Realtors and the Florida Apartment Association, a group which advocates for the interests of the multifamily rental industry, who said that there was no housing emergency such that rent control was justified under the law. Florida’s Supreme Court declined to hear the case effectively affirming the lower court’s decision striking down the ordinance on these grounds.

Then in 2023, the Florida legislature determined that they would preempt local government’s ability to enact rent control entirely with the passage of the Live Local Act. As of today, all local governments are forbidden from enacting rent control in their areas even in the case of a housing emergency.

![[F]law School Episode 13: The Migrant Trap](https://theflaw.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Drury_FB2-e1742192209662-640x427.png)

![[F]law School Episode 7: Profit Over People](https://theflaw.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/Housing-Podcast-Episode-hero-image-640x427.webp)