Welcome to the stage, Cora Poratization!

“Drag used to be ‘fuck the system’ and now drag is the system.”

Grayce Burns

November 7, 2024

Introduction

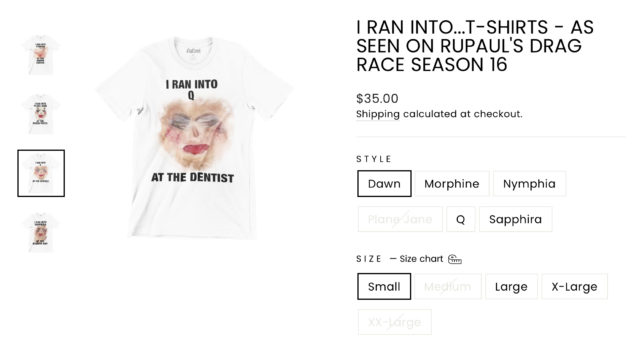

Ever wanted to meet your favorite drag performer? Great! That’ll be $60 (ticket to show not included.)

$60 too much? Purchase a t-shirt instead– only $45! (shipping not included.)

Don’t even ask about seeing live performances– premium tickets to once-free shows will now set fans back as much as $142, excluding fees. For fans wanting to catch a glimpse of Mother Ru herself, one StubHub listing is charging $1,031 for a spot in the eleventh row of the theater.

Can’t afford to support your favorite queens in person? That’s ok, just enjoy drag from the comfort of your own living room– but is that really supporting drag at all?

The art of drag, or “entertainment in which performers caricature or challenge gender stereotypes (as by dressing in clothing that is stereotypical of another gender, by using exaggeratedly gendered mannerisms, or by combining elements of stereotypically male and female dress) and often wear elaborate or outrageous costumes” has a long and storied history.

What started as a subversive artform embraced by the queer community has become, to many, yet another tool whereby corporations separate citizens from their hard earned doll-hairs.

This shift in the perception and management of drag has happened in mere decades. Gone are the days of drag shows in underground nightclubs or as part of impromptu performances at gatherings of queer community members. Since the advent of shows like “RuPaul’s Drag Race,” “Dragula,” and “We’re Here,” drag is more popular now than ever before.

But what does this popularity mean for those involved in creating this art?

Some performers long for the days that drag was less polished and not corporatized for public consumption. Others argue for the continuation of this perception of drag, believing drag’s popularity to be a valuable way for queer community members to find success in modern entertainment spheres.

So, what should be made of all of this? Does a more corporatized culture of drag help uplift queer voices, does it harm those that the artform was meant to celebrate, or something in between?

What follows is an exploration of the history of drag and those who have helped shape this artform. This overview will lead us into a deeper look at the growth of drag in recent years and the industries and dynamics that have evolved thanks to drag’s commercial success.

We will also hear from some of the largest names in the drag queen community on how this change has impacted them and how they view the industry developing. Specifically, we dive into these questions with academic and “RuPaul’s Drag Race” alum Tempest DuJour, legal name Patrick Holt, who is an Associate Professor at the University of Arizona in the School of Theatre, Film, and Television. BenDeLaCreme, stage name for Benjamin Putnam, independent production company owner, Seattle cabaret mainstay, and Drag Race participant, will also offer her thoughts. Enigmatic creator and Drag Race contestant Tammie Brown, also known as Keith Glen Schubert, will add her thoughts. Last, but certainly not least, we will chat with the “Cuntageous” drag icon and “Wigstock” founder Jon Ingle, who performs under the stage name Lady Bunny.

Ultimately, it seems that drag may be experiencing its very own industrial revolution, characterized by a period of previously unseen demand, and therefore, exploitation. However, we must ask ourselves whether we can allow this economic boom even though it takes advantage of those who have already suffered centuries of discrimination and prejudice.

Drag History

While authors such as Esther Newton, Roger Baker, and Meredith Heller have written extensive histories of queer culture and the development of drag, an overview of the artform’s history will help us analyze the industry’s changes over the past few decades. Likewise, while there are many types of drag beyond simply drag queens, the focus of this article is on the commercial success of drag queen culture. Nevertheless, I recognize the important role of drag kings and non-binary drag in queer and popular culture.

Many know that the tradition of cisgender men dressing as cisgender women goes back to the time of the agora and the amphitheater. Over time, men adopted aspects of what we would now call “femininity” as signifiers of social status. Louis XIV’s high heels and Thomas Jefferson’s powdered wig often come to mind when one thinks of historical men in “drag.”

A recent Harvard Law Review article utilizes this fact to defend the notion that the Founders would have fought against drag bans in many parts of the country. I disagree with this conception of drag culture, American history, and the appropriation of “queer” identifiers as indicating that the Founding Fathers would have supported our modern drag.

Costume de Cérémonie de Messieurs les Députés des 3 Ordres aux Etats Généraux. Clergé – Noblesse – Tiers État. Translated title: Ceremonial costumes of the deputies of the 3 orders of the Estates General. Clergy – Nobility – Third Estate. Circa 1789. Courtesy of Harvard Fine Arts Library, Digital Images & Slides Collection d2018.02824. Source.

Simply put, one would be hard pressed to call these displays “drag.” Ask anyone who has ever put on a wig, and they will tell you that one can of hairspray does not a Dolly Parton make.

Drag is inseparably linked to the struggle for sexual, gender, and racial equality. For many performers “doing drag” is itself an act of political resistance and a display of solidarity with other marginalized communities.

Ask anyone who has ever put on a wig, and they will tell you that one can of hairspray does not a Dolly Parton make.

BenDeLaCreme identifies that “queer people who are unapologetically queer are just inherently doing something political. . . that is a political statement– is to not hide.” She continues, “the reason [political activism][] is in my art is not because I go in, and I’m like, this needs to be political. It’s just because…that’s what’s happening to me.”

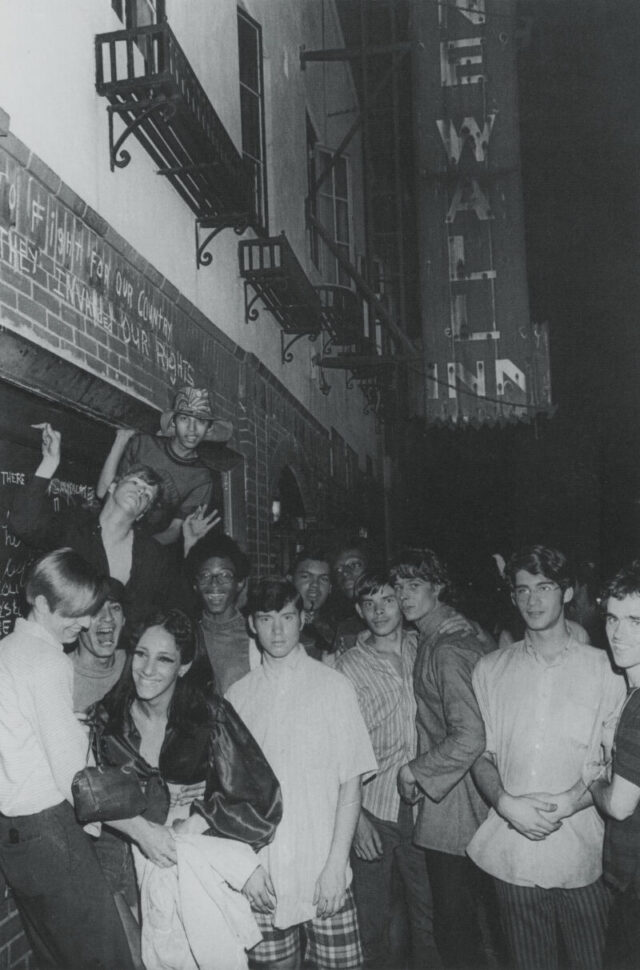

Christopher Street [pride] parade and anti-gay demonstration 1983. Photo courtesy of Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America, Radcliffe Institute. Source

Thus, to say that historical figures who adopted aspects of feminine dress, like French nobility or America’s Founding Fathers, were somehow early adopters or would-be supporters of drag would be an act of intellectual dishonesty.

So, if these early displays don’t constitute the beginning of drag as we know it, then when did drag start?

Scholars broadly agree that “drag” as a queer safe haven began in earnest sometime in the late 1800s. The earliest recorded drag gathering in the United States occurred in New York City in 1869, and was advertised as a masquerade ball. As the queer community became more interested in these events, their number and size grew; by the end of the 1920s, venues like New York’s Astor Hotel and Madison Square Garden had hosted “balls.”

Of particular import is the relevance that queer culture was beginning to have in mainstream society and how elites began to appropriate queerness. Harlem Renaissance activist Langston Hughes noted that these events, designed for those who were the most rejected by society, soon brought in throngs of “distinguished white celebrities.”

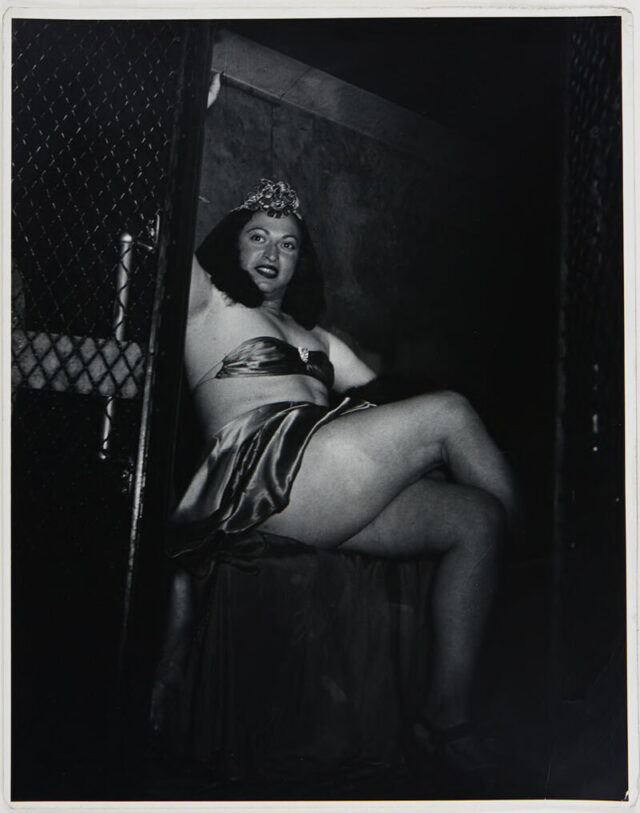

As drag grew in popularity, so did the establishment’s desire to curtail this cultural catalyst; police officers in metropolitan areas across the country soon operated on orders to arrest these individuals by any means necessary.

![[F]law School Episode 6: The Corporatization of Drag](https://theflaw.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/Burns_FeatureImage-640x427.jpeg)