As apex predators, wolves and humans have shaped the American landscape together for millennia. However, the carnage of the 19th century bison massacres, the near eradication of wolves in the lower United States, and Wildlife Services’ ongoing campaign of slaughter are recent, colonial introductions.

In contrast, many Indigenous peoples of the Americas maintained a “kincentric,” or familial relationship with nature, in which animals were viewed as part of an extended ecological family sharing common ancestral origins. Wolves were often regarded as “teachers” of humans, alerting them to crucial information about their environments. Some Indigenous Americans even kept domesticated canids, though cultures differed in whether these were distinguished as “dogs” rather than simply wolves. These Indigenous stewards of America’s lands were relatively new arrivals, having crossed the Bering Strait from Asia perhaps as few as 30,000 years ago. They discovered a continent on which canines had long dominated as apex predators, having evolved there millions of years earlier.

Wolves were essential ecosystem managers in North America long before humans ever encountered the New World.

Wolves were essential ecosystem managers in North America long before humans ever encountered the New World. As predators of elk, moose, bison, and deer, they have helped to prevent uncontrolled growth of large herbivore populations. This is an incredibly important ecological niche, since other than bears, there is a shortage of carnivores able to reliably prey upon these species. Large carnivores like wolves are also important because they competitively suppress medium-sized predators, such as coyotes.

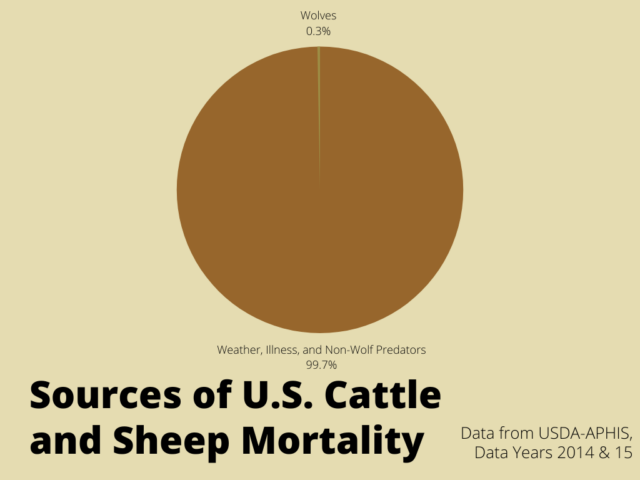

Despite their significance to humans and the ecosystems we rely on, not all cultures view wolves as kin, and people have sometimes held negative attitudes towards them throughout history. Wolves can be dangerous animals, with the potential to kill livestock, game animals, pets, and on rare occasions, humans. They are effective predators, pack animals able to endure bitterly cold weather, traverse long distances, and collaborate to take down prey many times their body size. As one Idaho hunter told New Yorker reporter Paige Williams, “They’re just too good at what they do.”

The risk of negative interactions with wolves increases as humans encroach into wolves’ territory. As game animals became depleted by colonists’ appetites and wild spaces were converted into agricultural pastures, American wolves’ historic hunting grounds and prey were replaced by farmland and relatively defenseless livestock.

There is also a cultural element to the fear and revulsion that wolves inspire among some. In myths, urban legends, and folk tales, wolves are typified as cunning deceivers, invaders in disguise who gobble up grandmas and little girls. For others, antipathy towards wolves is economic. Wolves occasionally consume animals intended for human consumption before they can be sold at market, and anti-predator measures to protect livestock from wolves cost farmers money. Political actors have often used wolves as a convenient scapegoat, attributing social ills to a predator species and then purporting to solve them through wolf extermination.

Due to a combination of these attitudes, American colonists nearly eradicated gray wolves from the lower 48 states by the mid-1900s. Much of this population decline began in the 19th century, driven by habitat loss related to urban, agricultural, and industrial development. Another significant portion of wolves were deliberately killed by private landowners. These wolves were trapped using spiked pits and other barbaric devices, shot in their dens, hunted with dogs, deliberately poisoned with tainted carcasses, tortured, and otherwise eradicated through any means with an often sadistic prejudice.

These wolves were trapped using spiked pits and other barbaric devices, shot in their dens, hunted with dogs, deliberately poisoned with tainted carcasses, tortured, and otherwise eradicated through any means with an often sadistic prejudice.

Wealthy livestock owners, particularly vociferous in promoting the cause of wolf extermination, succeeded in recruiting the government to their campaign. In 1906, the U.S. Bureau of Biological Survey was given the go-ahead by President Theodore Roosevelt to destroy wolves in response to claims of depredation by cattle ranchers. Subsequently, the Bureau became a wolf-extermination unit that destroyed thousands of animals, almost completely eradicating the species in the lower 48 states by 1950.

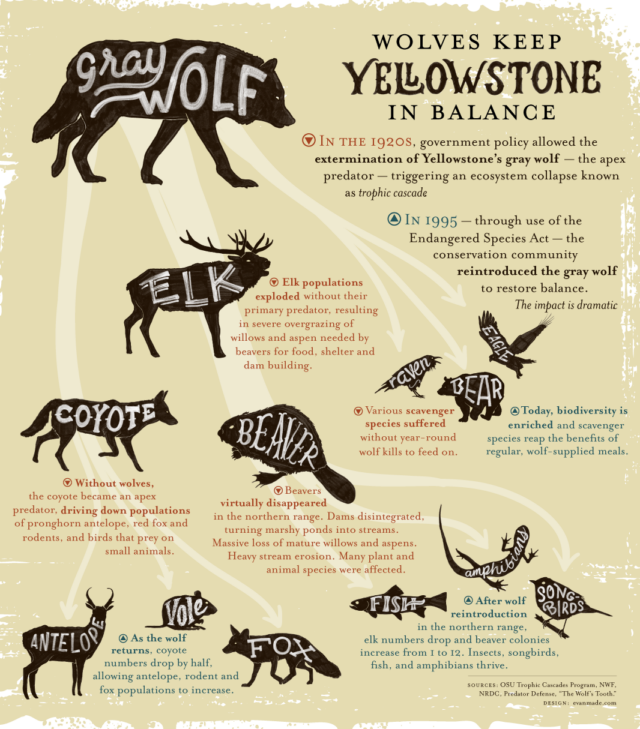

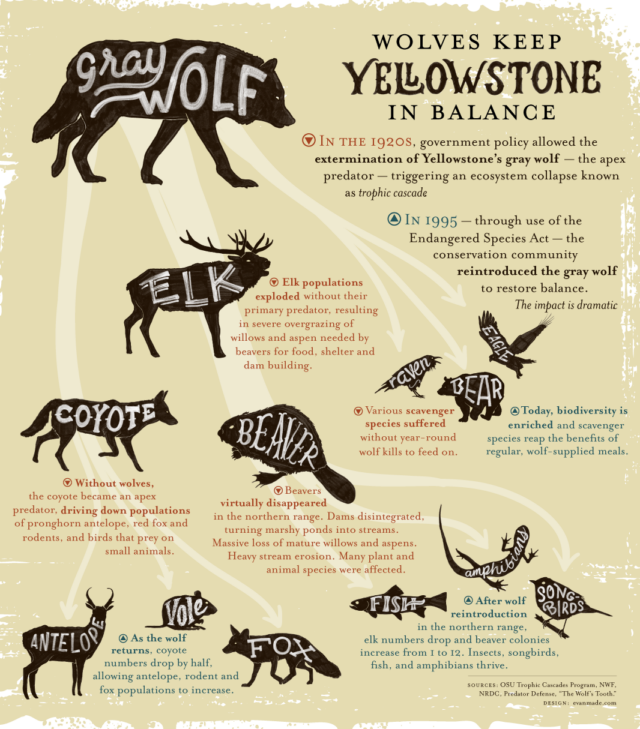

The extermination of American wolves had major, unpredicted effects on the environment. Apex predators like wolves play a pivotal role in regulating their ecosystems. In Yellowstone, one of the best-studied American ecosystems, the disappearance of the wolf was associated with a trophic cascade of harmful systemic effects.

Wolves keep Yellowstone in balance. Photo by Earthjustice.

For instance, scavengers formerly gathered to feed on carcasses of animals hunted by wolves. As wolves declined and eventually disappeared in Yellowstone, ravens, eagles, bears, foxes, and other opportunists were left with fewer sources of food.

Elk populations exploded when their predator counterparts disappeared from Yellowstone’s landscape. Over 70,000 elk had to be removed from the northern herd between 1932 and 1968. When park managers stopped culling elk, populations would grow again until hundreds of elk were dying of starvation in the wintertime. These excess elk overgrazed the park and competed with other herbivores for dwindling forage.

The elk also depleted the park’s willow and aspen trees, which provided nesting habitat and kept erosion at bay. Bison, which were also being hunted to near extinction at the time, are believed to have been negatively affected by this change in their environment. Beavers, which used these trees for food and dam construction, nearly disappeared from sections of the park as a result. Without the dams, deep pools that supported pond ecosystems vanished in kind.

Meanwhile, coyotes—mid-sized canid predators that wolves normally keep in check—expanded to occupy the ecological void left behind by larger predators’ absence. Increasingly dominant coyotes overhunted their prey animals, such as pronghorn antelope and rodents like mice and voles, until their stocks became depleted. Foxes, birds of prey, weasels, and other animals that compete with coyotes for prey were subsequently reduced in the park.

Following an increased appreciation of the importance of keystone predators in maintaining healthy ecosystems, and in response to a public backlash against the pollution of natural resources, President Nixon signed the Endangered Species Act (ESA) into law in 1973. The gray wolf was added to the list as an endangered species in 1978 (except for the population of Minnesota, which was listed as threatened). As part of their ESA protections, hunting of wolves was prohibited under the Act’s expansive “take” prohibition, which makes it illegal “to harass, harm, pursue, hunt, shoot, wound, kill, trap, capture, or collect” endangered species, “or to attempt to engage in any such conduct.”

The Endangered Species Act describes conservation as involving the restoration as well as protection of species, and in 1995, 41 wolves were released into the Yellowstone area in the hope of restoring the species to its previous role in the region’s ecosystem. The Yellowstone reintroduction has been a success, and there are at least 95 wolves in the park today. Around 6,000 gray wolves are estimated to live across the lower 48 states.

![[F]law School Episode 5: The Business of Boredom](https://theflaw.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/Reed_1-640x427.jpg)