On the same April morning when federal law enforcement officers ripped Kraig from his Connecticut home and his sleeping six-year-old son, helicopters whirred and sirens blared in the North Bronx. Over 700 officers, with no-knock warrants and guns drawn, broke into apartments and woke the sleeping families inside. Young children awoke, paralyzed with fear, to the sight of shouting strangers, dressed in riot gear and carrying weapons, stomping through their homes; teenaged girls were forced out of their beds, some in just their underwear, by screaming male officers who would not allow them to retrieve clothing from their bedrooms; mothers and grandmothers tried to comfort their families and calmly answer questions from officers demanding to know if they were hiding anyone else, while their husbands, sons, and grandsons lay face down, in their boxer shorts, with handcuffs around their wrists. 21-year-old Geovanni Martin tried to escape through a window and fell to his death (in a 2020 documentary entitled “Raided, Part 2” his best friend explains that she believes Geovanni feared for his life because, in 2012, police shot their unarmed classmate, Ramarley Graham, in his home). In short, the raid was a living nightmare.

In short, the raid was a living nightmare.

The U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York (SDNY), the New York Police Department (NYPD), U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), Homeland Security Investigations (HSI), U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), and the U.S. Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) SWAT teams rounded up and arrested 88 alleged members of two so-called “rival street gangs” in what later became known as the largest “gang raid” in New York City history. In total, 120 people were indicted; those who were not among the 88 arrested during the raid were already serving time for other convictions.

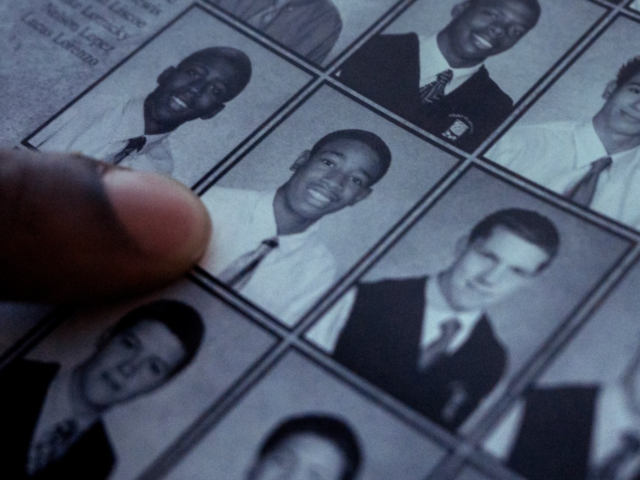

Perp-walk images of young Black and Brown men dominated the news—pictures of young men, in pajamas and handcuffs, trying to cover their faces as police loaded them into vans. The majority of the arrestees were in their late teens and early twenties, with their entire lives ahead of them. Even though these young men were still legally innocent, the U.S. Attorney’s Office published a long list of their names in its press release about the raid.

The SDNY indictments, formally entitled United States v. Burrell and United States v. Parrish, alleged racketeering conspiracy, narcotics conspiracy, narcotics distribution, and firearms charges. It was later reported by two professors, Babe Howell (of CUNY Law) and Priscilla Bustamante (of Baruch), that dozens of the young people arrested weren’t actually in gangs; rather, many of the arrests were based on whom the individuals knew, rather than what they actually did, i.e., guilt by association:

One of the most startling revelations of the review of the Bronx 120 prosecutions is that half of those swept up in the largest gang raid in the history of New York were not affirmatively alleged to be members of either of the two rival gangs allegedly targeted by the mass indictments. The prosecutor’s sentencing submissions…affirmatively state that 34 of those subjected to the raid and arrested as part of the RICO case were not gang members. An additional 17 individuals are characterized as “associates of” or “associated with” the two rival gangs…. Thus, 51 of the defendants swept up in “the largest gang takedown in New York City history” were affirmatively not alleged to be gang members. For another 13 there is no clear allegation relating to gang membership. Their dispositions suggest they were not gang members.

The Bronx 120 Raid destroyed lives, families, and communities: 80 of the young men and teens arrested were not charged with violent offenses. Over 100 took plea deals, regardless of their actual guilt. Two of the five murders cited in the indictment had already been solved before the raid even took place. Over 90% of the people arrested were U.S. citizens, but ICE nonetheless played a significant role in the raid, due to its “transnational gang program” (a program that can be triggered by just one non-citizen in a group of acquaintances allegedly participating in some form of illegal activity). The New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) responded to the raid by investigating families in apartments where someone had been arrested; at least one mother whose child was named among the Bronx 120 defendants was evicted and became homeless as a result of the NYCHA investigations.

None of this mattered—not at the time of the raid and not thereafter. Law enforcement insisted that these young men were dangerous—guilty by association—and urged that the public safety benefit of the militarized raid sufficiently outweighed the costs of the raid for those affected.

Alice Speri, a reporter for The Intercept, spoke with families affected by the raid. They told a very different story: “[I]n community meetings and private conversations, local residents have expressed rage over the raids and said that when they asked for safer neighborhoods, they didn’t mean officers in riot gear breaking into their apartments in the middle of the night and taking away their children.”

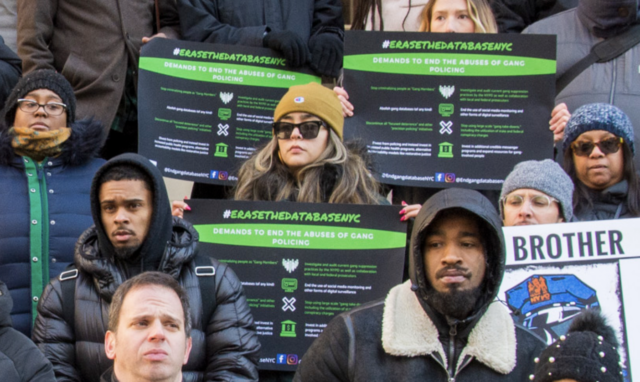

Similarly, Professor Babe Howell questioned, in an article she wrote after the Bronx 120 Raid, why law enforcement decided against simply working directly with community members instead of relying upon secret surveillance tactics and information gathering technologies:

First, one may question the wisdom of watching, listening, spying, waiting and then using conspiracy charges to link dozens of young people to offenses committed by others instead of intervening to defuse the rivalry. Second, one may wonder how a military-style raid to accomplish regular law enforcement goals affects police-community relations. Having obtained the indictment and surveilled the individuals for years, why enter their homes wearing bulletproof vests, with firearms drawn, pointing weapons at family members, [with] helicopters overhead?

How did a massive “precision policing” so-called gang raid, carried out by hundreds of officers from half a dozen federal law enforcement agencies, arrest and publicly brand as “dangerous criminals” so many non-gang members? How did a highly coordinated action, with massive resources at its disposal, place innocent young people on a path to that basketball court behind razor wire, or worse—adult prison? And why were so many of these young people sent to prison under the extreme threat of the RICO Act? In order to answer those questions, we’ll have to examine the flawed bedrock of so-called precision policing: gang databases and police surveillance technology.

Caption Required by NY Daily News – Nearly 100 Bronx gang members were arrested early Wednesday, April 27, 2016 as police and federal authorities conducted a massive gang sweep at the Eastchester Gardens houses and other locations in the Bronx. (Anthony Delmundo/New York Daily News)

Permission for use granted by New York Daily News. Image was originally used in: 120 Bronx Gang Members Indicted in Largest Takedown in NYC History: Look Back at 87 Arrests in One Day, N.Y. Daily News (Feb. 25. 2019).