These examples illustrate why police were outsiders to the labor movement in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Union activists were concerned about the “divided loyalties” of police officers, and unions such as the American Federation of Labor rebuffed applications from police to join their ranks. Aaron Bekemeyer, a historian at Harvard who studies labor and police in the 20th century, explained that “the broader labor movement wasn’t particularly interested [in police joining] because the function of police was disempowering unions and breaking strikes.”

“the broader labor movement wasn’t particularly interested [in police joining] because the function of police was disempowering unions and breaking strikes.”

The government was also opposed to police unionizing. When the Boston Police Department went on strike in 1919, then-Massachusetts governor Calvin Coolidge proclaimed, “There is no right to strike against the public safety by anybody, anywhere, anytime.” All 1,147 officers who went on strike were fired and replaced. President Woodrow Wilson denounced the strike as “a crime against civilization.” For decades afterwards, there was bipartisan opposition to police unions.

Fast forward a hundred years later, and the Boston police union—the Boston Police Patrolman’s Association (BPPA)—is an entrenched fixture in the city. What changed to allow police unions like the BPPA to become some of the most powerful unions in the labor movement?

In the 1960s and 1970s, states began granting public-sector workers the right to collective bargaining, which allowed police officer associations, lodges, and orders to become unions. Around the same time, police unions pointed to the urban rebellions in the 1960s, such as the anti-war and Black power movements, as justification “law and order.” Once police unions gained “the right network of supporters to enable them,” said Bekemeyer, “police unions transform[ed] from a threat to the public interest [to] being linked to the public interest.”

One of these key supporters was Ron DeLord, whom The New York Times recently described as “a fiery former Texas cop turned labor organizer.” DeLord wrote Police Association Power, Politics, and Confrontation: A Guide for the Successful Police Labor Leader—the playbook police unions nationwide have followed for decades. According to the New York Times,

The book repeatedly urges union leaders to ignore the “losers,” “whiners” and “naysayers” in their way. “A police association leader must throw out all those traditional notions of right and wrong,” it exhorts. “So long as it’s legal, you do what you gotta do to get where you’re going!” It also quotes one San Antonio union official saying, “If all else fails, we’ll drop the bomb and live in the ashes.”

The playbook advises police unions to win favorable terms through fearmongering, public smear campaigns, and intimidation. When New York City police officers faced layoffs in the 1970s, they passed out “Welcome to Fear City” pamphlets that warned tourists to leave the city. In San Antonio, the police union sent a fancy gift basket with a dead rat to a city councilman who tried to cut police costs.

Welcome to Fear City pamphlet title page, republished by the zine Research and Destroy New York City.

“Aggressive, consistent PR strategy is something you see a lot with police unions,” Bekemeyer explained. It was “particularly important when police didn’t have collective bargaining early on to achieve the things they wanted to achieve, and it remains really important to them. Today, police constantly talk to the media to warn that moderate efforts to increase police oversight are detrimental to a safe society and to blame any uptick in crime to progressive social movements.”

Another important player in the rise of police unions are the labor lawyers who represent them. Although lawyers are often less visible than belligerent police union leadership, they can play a consequential behind-the-scenes role to intimidate and outmaneuver those who don’t go along with their clients’ agendas.

The now-defunct law firm Lackie, Dammeier, McGill & Ethir (Lackie Dammeier) illustrates the lengths lawyers have gone to in service of their police union clients. Lackie Dammeier represented over 130 police unions throughout California and advertised its attorneys as “Former Cops Defending Current Ones.” On its website, policeattorney.com, was a “negotiation” playbook that advised police unions to “keep the pressure up until that person assures you his loyalty and then move on to the next victim.”

In 2012, the Costa Mesa Police Officers’ Association retained Lackie Dammeier to perform “candidate research” on Costa Mesa City Council members in the lead up to the city council election. As part of this research, Lackie Dammeier hired private investigators to track council members who advocated for police budget cuts. This scheme came to light only after one of the private investigators falsely reported a council member for drunk driving. The private investigator was sentenced to one year in jail, and the council member settled its claims against Lackie Dammeier for $600K. Although Lackie Dammeier closed shortly thereafter, one of its partners, Dieter Dammeier, opened his own law firm and now specializes in litigating police overtime pay.

Another important player in the rise of police unions are the labor lawyers who represent them. Although lawyers are often less visible than belligerent police union leadership, they can play a consequential behind-the-scenes role to intimidate and outmaneuver those who don’t go along with their clients’ agendas.

As a result of the aggressive tactics of police unions and their supporters, police unions have overcome their turbulent history and are an inexorable force in today’s labor landscape.

Police Union Power Today: Why Police Don’t Belong in the Labor Movement

All labor unions seek to (1) grow their membership, (2) build solidarity among their members, and (3) wield political and economic influence to pursue their interests. Police unions have excelled at all three of these aims. Yet as police unions thrive, workers and the broader labor movement suffer.

First, policing is a heavily unionized occupation. The union membership rate among U.S. workers was 10.1% in 2022. In contrast, more than 80% of sworn officers are part of a labor union. Professor Sharon Block, an expert on labor law and the Executive Director of the Center for Labor and a Just Economy at Harvard Law School, explained that police unions have extremely high rates of membership. Where there is a unionized police force, it’s not unusual for 100% of officers to be union members.

Since police serve to protect property and preserve the status quo, it makes sense that in our capitalist system, police unions have flourished while other labor unions are on the defensive. This disparity reflects what kinds of power the state wants to cultivate, and what kinds of power the state wants to extinguish.

In contrast to police unions, the labor movement in general is in a precarious position. Professor Benjamin Levin considers police unions an “incongruous manifestation of contemporary labor’s power” given that “union power in the United States has hit a nadir. Less than eleven percent of the labor force is unionized—a lower percentage than at any point since World War II.” The imbalance between police unions and other labor unions is attributable to the preferential treatment police unions receive from state and local governments. Police unions generally benefit from bipartisan support, even from conservative politicians who oppose labor organizing. Wisconsin effectively abolished collective bargaining for public-sector employees in 2011, but it made an exception for police unions. Most recently, the Florida state legislature passed a bill that will severely weaken public-sector unions, with a special carve-out for those that represent law enforcement officers, correctional officers, and firefighters.

Since police serve to protect property and preserve the status quo, it makes sense that in our capitalist system, police unions have flourished while other labor unions are on the defensive. This disparity reflects what kinds of power the state wants to cultivate, and what kinds of power the state wants to extinguish.

Second, police unions are incredibly successful at building solidarity among officers. One of the most infamous examples is the “blue wall of silence,” the informal code among police officers to keep misconduct under wraps. The police killing of Laquan McDonald, a 17-year-old Black teenager, in 2014 demonstrates how the blue wall of silence operates. When police responded to a report that someone was breaking into cars, Chicago police officer Jason Van Dyke was one of the last officers to arrive on the scene. Within seconds of getting out of his car, Van Dyke shot McDonald 16 times. Afterwards, Van Dyke claimed that he killed McDonald in self-defense. Other officers corroborated his story. But a year later, video footage of the shooting showed that Van Dyke shot McDonald as he was walking away, and three officers were charged with conspiring to cover up the murder. Although they were acquitted after a contentious trial, a task force report commissioned by the mayor found that:

“The collective bargaining agreements between the police unions and the City have essentially turned the code of silence into official policy. The CBAs discourage reporting misconduct by requiring affidavits, prohibiting anonymous complaints and requiring that accused officers be given the complainant’s name early in the process. Once a complaint is in the system, the CBAs make it easy for officers to lie if they are so inclined —they can wait 24 hours before providing a statement after a shooting, allowing them to confer with other officers, and they can amend statements after viewing video or audio evidence. In many cases, the CBAs also require the City to ignore or even destroy evidence of misconduct after a certain number of years.”

If word of an officer’s misconduct makes it beyond the “blue wall of silence,” police unions are there to organize a full-throated defense.

Police unions therefore reinforce the blue wall of silence through the contract terms they negotiate with municipalities. And if word of an officer’s misconduct makes it beyond the “blue wall of silence,” police unions are there to organize a full-throated defense. Chicago’s police union steadfastly supported Van Dyke—who had accumulated 20 documented citizen complaints, mostly for excessive force, during his 17 years in the department—when he was charged with killing McDonald. After he was convicted, Chris Southwood, the Illinois Fraternal Order of Police (FOP) President, warned that:

“This sham trial and shameful verdict is a message to every law enforcement officer in America that it’s not the perpetrator in front of you that you need to worry about, it’s the political operatives stabbing you in the back. What cop would still want to be proactive fighting crime after this disgusting charade, and are law abiding citizens ready to pay the price?

Another example of police union solidarity is the case of former Philadelphia Police Inspector Joseph Bologna. Bologna, a high-ranking bike cop in the department, attacked protestors during Black Lives Matter protests in May 2020. After video footage of two separate attacks went public, Bologna was charged with aggravated assault. John McNesby—the president of Philadelphia’s FOP lodge who had previously called BLM protesters “a pack of rabid animals” at a press conference—told reporters that he was “disgusted” by the fact that Bologna had been charged at all. To support Bologna, the union sold “Bologna Strong” merchandise on its website.

Pictures and alt text published in an article on Philly Mag.

Although police exhibit formidable solidarity among their ranks, this solidarity typically doesn’t extend to other workers in the labor movement. Most police union members are independent from other labor organizations. The largest police organization, the Fraternal Order of Police, has approximately 354,000 members but does not affiliate with any of the major labor federations. The distance between police unions and the rest of the labor movement means that “they’re at best marginally involved with the most pressing mission of today’s labor movement, which concentrates on organizing many of the same low-wage, service-sector communities of color who are disproportionately abused and harassed by police,” argues labor activist Kim Kelly. “Even the basic terminology is different,” Kelly notes. “These organizations are usually broken down into ‘lodges’ instead of ‘locals,’ and are more often known as ‘associations’ rather than unions.”

Another reason that police rarely express solidarity outside of their own is that their job involves the surveillance, harassment, and abuse of other workers, particularly among poor communities of color. The interests of law enforcement, writes Kelly, “are diametrically opposed to those of the workers whom the labor movement was launched to protect.” And, as described above, throughout the history of the labor movement police have played a pivotal role in intimidating workers and busting strikes to maintain “law and order.”

Although police exhibit formidable solidarity among their ranks, this solidarity typically doesn’t extend to other workers in the labor movement.

Bekemeyer notes that there are some instances of synergy between police unionists who see themselves as labor leaders and unions like AFSCME that think the best way to grow worker power is to bring police within the labor movement. “These connections are possible, and they’ve happened, but they’re more tenuous,” says Bekemeyer. And it’s the cases where “police unions and other workers come together [that] government cracks down” on labor the hardest.

Third, police unions are incredibly successful at amassing both political and economic power. One of the most effective weapons in their arsenal are collective bargaining agreements (CBAs), through which unions secure contracts that grant officers favorable pay, benefits, and disciplinary procedures. Most states allow or require municipalities to bargain collectively with police unions. As a result, police union contracts—often negotiated outside of public view—shape what policing looks like across the country, from how much money police departments get to how insulated police officers are from their own misconduct.

A groundbreaking study by Professor Stephen Rushin found that police union contracts frequently contain provisions that impede officer discipline and police reform. Of the 178 contracts Rushin analyzed, a substantial number of them limited officer interrogations after alleged wrongdoing; mandated the destruction of officer disciplinary records; banned civilian oversight of police misconduct; prevented anonymous civilian complaints; indemnified officers in civil suits; or required arbitration in cases of disciplinary action. According to Rushin, these provisions thwart legislative attempts to promote police accountability and transparency, and they narrow the field of reforms that the Department of Justice’s Civil Rights Division can request of police departments.

In another study, Rushin examined the disciplinary appeals processes established by police union contracts in over 600 cities and concluded that, due to union contract provisions, police departments must often rehire or significantly reduce disciplinary sanctions against officers who have engaged in serious misconduct. Similarly, a Washington Post analysis of 1,881 officers fired by the nation’s largest police departments from 2006 to 2017 found that departments were forced to reinstate more than 450 officers after appeals required by police union contracts.

Not only does research show that police CBAs make responding to police violence harder, but it also indicates that collective bargaining rights can actually lead to an increase in police misconduct. A recent paper found that granting collective bargaining rights to law enforcement in Florida caused a substantial increase in violent incidents of misconduct among sheriff’s offices. Another study looking at cities across the country between 1959 and 1988 found a substantial rise in civilian killings after police gained collective bargaining rights—amounting to approximately 60 to 70 additional people killed by police per year.

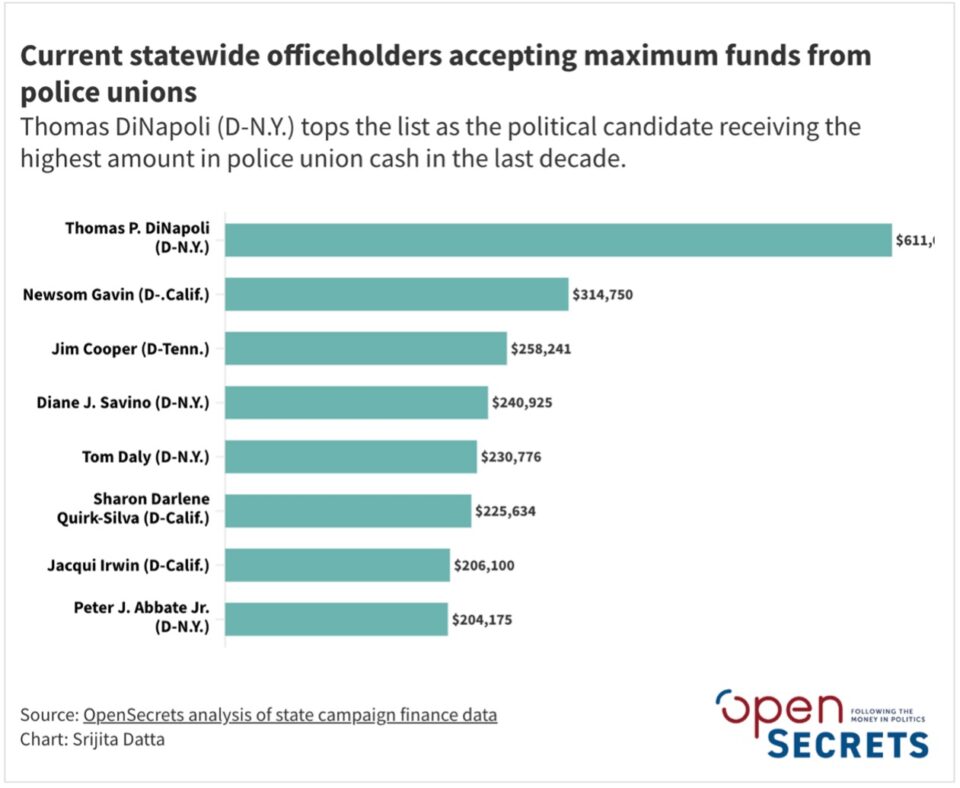

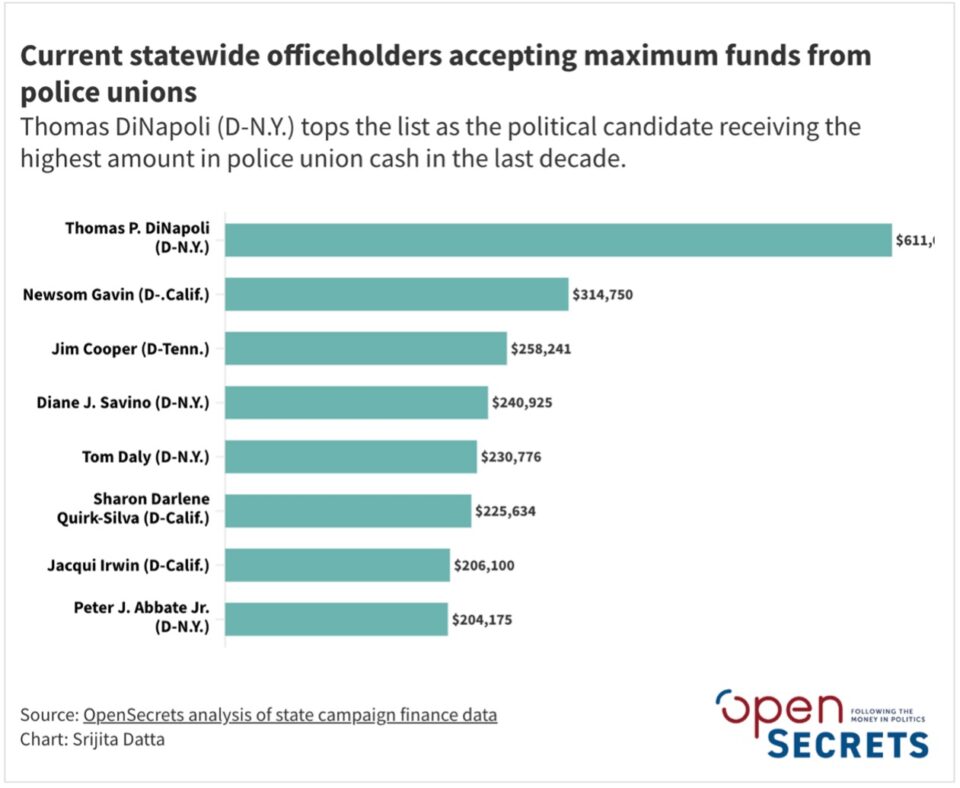

In addition to collective bargaining, police unions exert substantial power through lobbying. According to data tracked by OpenSecrets, police unions and associations have spent over $48 million on state lobbying and contributed almost $71 million to state-level candidates and committees in the last decade alone. Congressional campaigns have received over $1.2 million from more than 50 law enforcement unions and PACs since the 1994 election cycle. Police lobbying has pushed 24 states to adopt Law Enforcement Officer Bill of Rights (LEOBRs), statutes which grant police officers extra procedural rights in disciplinary processes that restrict investigations into misconduct, limit discipline, restrain transparency and civilian oversight, and conceal evidence of misconduct.

Chart created by Srijita Datta using OpenSectrets data.

Given the long history of police harassing, intimidating, assaulting, and killing other workers, particularly workers of color, do police unions fit within the labor movement?

For labor activist Kim Kelly, the answer is no. “Labor unions exist to protect people; police exist to protect property,” says Kelly. “Ultimately, police unions protect their own, and the contracts they bargain keep killers, domestic abusers, and white supremacists in positions of deadly power,” Kelly wrote for The New Republic. “The only solidarity they show is for their fellow police officers; other workers are mere targets. Their interests, as well as those of other right-wing oppressors’ unions like those that represent ICE, border patrol, and prison guards, are diametrically opposed to those of the workers whom the labor movement was launched to protect.”

Professor Sharon Block’s response to this question is more cabined. “As a basic matter, all public-sector workers should have a right to collective bargaining and be represented by unions.” But “it’s a different question to ask whether the FOP or IUPA [International Union of Police Associations] should be welcomed into the mainstream labor movement and be accorded the same solidarity and status as other unions…on a personal level, [my] answer is no. They’ve done a real disservice to their communities and rarely act in solidarity with other workers.”

Bekemeyer echoes this sentiment, although he frames the fundamental question in a slightly different way. “As long as people have jobs, they should be able to unionize,” he expressed. This principle raises the question of what to do when there’s something inherently destructive with the work itself. People in the labor movement often “don’t want to raise issues about the moral value of work; just being a worker entitles you to certain rights.” Bekemeyer analogized police jobs to jobs in extractive industries, like coal mining, and posited that perhaps the answer may be to get rid of the job altogether. “It’s tricky to work through these questions about, say, maybe we don’t want a world in which people are mining coal anymore, but how do you approach that in a way that’s not damaging to the livelihood of workers,” Bekemeyer said. “The answer to those questions ideally come from the workers being a part of the conversations to build a path to alternative work.”

Given the long history of police harassing, intimidating, assaulting, and killing other workers, particularly workers of color, do police unions fit within the labor movement?

Professor Benjamin Levin’s article, What’s Wrong with Police Unions?, characterizes the implications from this line of questioning neatly. “Maybe police deserve higher pay and better parental leave. Or maybe they don’t. But if you don’t believe that police should have a job in the first place, these questions are moot.”

Reformist Critiques of Police Unions

Calls for police reform abounded in the aftermath of George Floyd’s murder and the subsequent racial justice uprisings. The fact that Derek Chauvin was the subject of at least 22 complaints or internal investigations before he murdered George Floyd—only one of which resulted in discipline—shone a spotlight on the role of police unions in enabling and immunizing police misconduct.

To solve these problems, labor law scholars have proposed reforms that would change what police unions are able to bargain for and how they can bargain for it. Such reforms include prohibiting police unions from bargaining over anything beyond wages and benefits; making police disciplinary records and arbitration decisions more accessible; opening up police contract negotiations to the public; requiring disciplinary terms to be developed with public input; and providing a way for rank-and-file officers to form minority unions.

But these calls for reform have been met with caution from some labor activists and lawyers, who, like Harvard Law Professor Benjamin Sachs, worry that reforms could be weaponized against other public-sector unions and “undermine the incredibly valuable work these other unions do to advance the interests of teachers, nurses, sanitation workers, and public servants of all kinds.”

For Sharon Block, this possibility is “definitely a concern because of the fundamental importance of public-sector unionism and how much it’s been under assault.” But “carefully drawn boundaries [to curtail police union power] can be justified because police unions have abused their collective power, and they have a unique capacity to inflict harm,” explained Block.

This idea that police unions are unique has been cited by many proponents of police union reform. Because police—unlike other public-sector workers—wield the distinct power to use violence, they require different collective bargaining rules to prevent abuses of this power. Advocates of labor law reform offer this rationale to justify weakening police unions in a way that, theoretically, wouldn’t apply to other public-sector workers.

In a podcast episode with Working People, organizer Halimat Alawode warned that this distinction may not hold in reality. “People are asking questions about police officers’ collective bargaining rights…[but] not everyone who is interested in the issue of policing fully grasps the issue of labor.” Alawode continued that:

“We need to be smart, as members of labor, if we want that [the end of police unions] to be an internal or an external push. Because we know labor. We know that we can push them out and protect our collective bargaining rights. [If] it becomes an external push, are we going to allow our collective bargaining to become sacrifices in that push? That’s what’s on the line for us right now… They will not do it with the care that we want it to be done with. They will not do it with the understanding of the history of labor. And I don’t want to go with the cops.”

If pursuing labor law reforms to disempower police unions could have unintended consequences on public-sector unions generally, what is the best way to confront the problems police unions pose? Levin suggests that “we might understand the critiques of police unions as actually having little to do with unions, organized labor, or the relationship between workers and bosses. Maybe the problem isn’t police unions; maybe the problem is police.”

![[F]law School Episode 12: The Body (S)camera](https://theflaw.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/POOKKULAM_HERO-e1728232922783-640x427.jpg)