When Healthcare Doesn’t Care

How Privatized Healthcare Harms Inmates and What Can Be Done

Tuhin Chakraborty

February 13, 2024

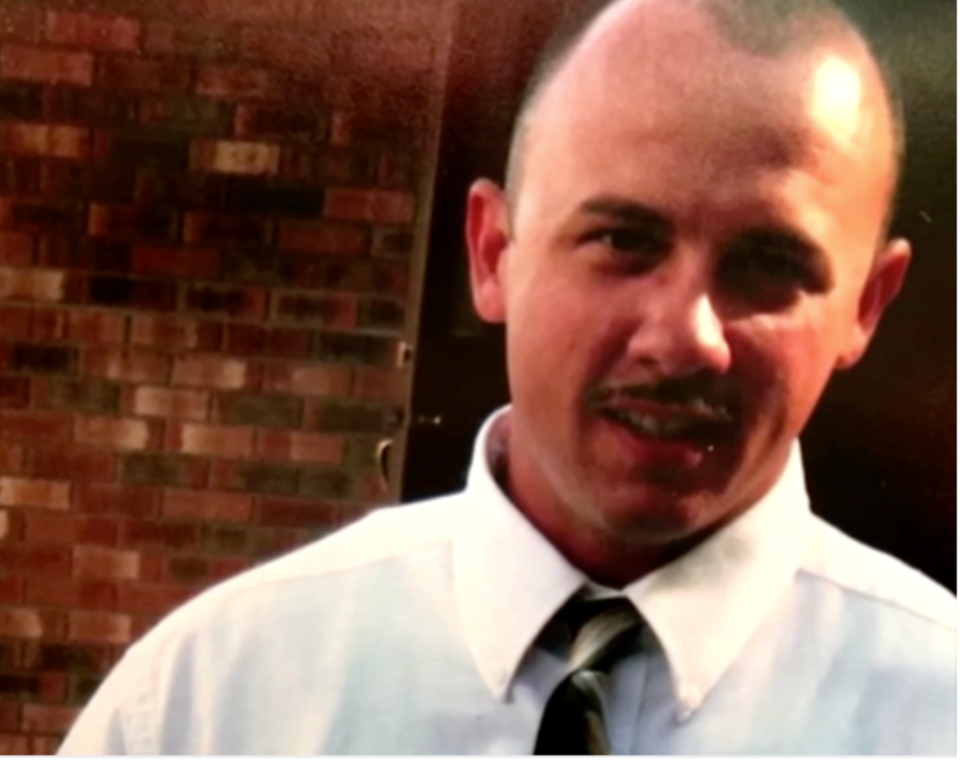

Five years ago, Wade Jones exited a grocery store in Kent County, Michigan after stealing four fifths of alcohol. He was caught and charged with retail fraud. His formal penalty was five days in jail starting April 24, 2018. What he received instead was medical neglect so egregious that he was fatally injured less than three days into his jail sentence.

Mr. Jones was, what his family’s lawyers called, a “functional alcoholic.” It’s what might have motivated his initial offense in the first place. When he was in jail, unable to access alcohol, he began to suffer the debilitating effects of withdrawal. On April 26, 2018, Mr. Jones began to hallucinate and pick at his skin, common signs of delirium tremens, a severe condition linked with alcohol withdrawal that can be fatal if left untreated. The medical staff at the jail did not even come close to meaningfully noticing the danger Mr. Jones was in, let alone treating him. His family’s attorneys claim that no doctor was summoned when Jones began exhibiting symptoms. On April 27, Jones lost consciousness over a toilet in a cell specifically intended for observation; afterwards, nobody checked on him for eight minutes. A defibrillator was then brought over, but allegedly turned off because the battery had not been changed. By the time Jones was finally taken to a hospital, he had suffered from cardiac arrest, a condition that contributed to his eventual death on May 2. Perhaps the most painful detail of this horrific episode is how preventable it was. Jones’s symptoms could have been alleviated early on with diazepam, commonly known as valium. In other words, a common anti-anxiety drug might have been the difference between life and death for Wade Jones, and those responsible for his care failed to act.

While justice never came for Mr. Jones during his lifetime, his family was eventually able to receive $6.4 million in damages against three employees of the private company, Corizon Health, whose staff (mis)handled Wade Jones during his time in jail. The Michigan-based plaintiff’s law firm Buckfire Law began the lawsuit in January 2020 alleging that Corizon violated Wade Jones’ Eight Amendment rights by failing to provide “humane conditions of confinement” and “take reasonable measures to guarantee the safety of the inmates.” According to Buckfire Law Attorney Jennifer Damico, “The Defendants had numerous chances to save [Wade Jones’s] life. They made conscious and repeated decisions to not act — and the Jury found their conduct to rise to the level of deliberate indifference.”

Wade Jones’s story is far from alone in the world of privatized carceral healthcare. Corizon alone has been sued for negligence and other issues over 660 times during the last eight years, with stories similar to Wade Jones’ being repeated over and over again in courts across the US. Corizon actually rebranded as YesCare in 2022 after complex bankruptcy maneuvering to help clear itself of debt and negative publicity. The corporation and its affiliates have had other names over the last names (for simplicity, YesCare will continue to be referred to here as Corizon since much of the legal action mentioned in this article started when YesCare was still Corizon). While the lawsuits caused Corizon to lose contracts with government corrections agencies in multiple states, including in Michigan, it still manages at least 139 facilities in 15 states as of December 2022, with likely tens of thousands of inmates under its care. In 2021, Corizon succeeded in renewing a substantial contract with the Wyoming Department of Corrections to serve multiple facilities across the state for up to five more years. Ironically, the rationale given by the Wyoming Department of Corrections for the renewal was Corizon’s professional effectiveness and “high level of medical services,” even though the plethora of aforementioned litigation (including Jones’s) was exposing the company’s healthcare management problems at that time.

“The Defendants had numerous chances to save [Wade Jones’s] life. They made conscious and repeated decisions to not act — and the Jury found their conduct to rise to the level of deliberate indifference.”

So how do companies like Corizon remain operational, even after such poor care and the associated attempts to hold them accountable? The answer lies in the dominant economic narrative surrounding private contracting in American carceral healthcare. Since the 1970s, a multitude of state and local governments began enlisting private companies as a relatively cheap way to provide legally required health services to inmates, while protecting the government from direct liability and related litigation costs, since the government would no longer be the primary care provider. According to Bianca Tylek, Executive Director of the carceral welfare advocacy group Worth Rises, “a large reason why states are moving to privatized care is because they get promised the idea of lower-cost healthcare” since healthcare costs “[are] the second-largest budget line item for correctional facilities.”

“The way in which they provide cheaper care is by cutting costs in [care] provision, and therefore cutting, in many cases, quality.”

However, the economics here has major issues. According to Ian Cross, another Michigan attorney who is suing Corizon for malpractice contravening the Eight Amendment, instead of directly expending resources on carceral healthcare, states or local jurisdictions grant contracts to private companies in at-times competitive bidding processes. The winner is very often the company who promises to provide care for inmates at the lowest possible cost. Once the contract is won, the state or local government will frequently pay these companies on what is known as a capitated basis, where the contractor is paid a fixed sum of money in advance per inmate with that money being intended to cover all of the inmate’s healthcare needs. This process of capitation creates a very large perverse incentive for carceral healthcare companies to spend as little as possible on actual inmate healthcare and pocket the rest of that fixed sum as profit. As Ms. Tylek makes clear, “the way in which they provide cheaper care is by cutting costs in [care] provision, and therefore cutting, in many cases, quality.” While one might argue that such a focus on financial efficiency happens in all insurance industries, unlike free people, incarcerated people cannot choose healthcare plans, so carceral providers have little countervailing incentive to keep customers happy. This makes their tendency to neglect quality more problematic.

Another issue with the economic analysis behind carceral healthcare privatization is that it might be more cost-shifting than cost-cutting. Private companies failing to properly implement effective solutions to inmates’ health issues may lead to those issues becoming significantly worse when those people are released. Since they have just been released from prison, former inmates are frequently “indigent” and qualify for Medicaid. This means that “Medicaid has to pay for the healthcare that was never provided during…. incarceration.” In other words, taxpayers might not really be saving that much money, since Medicaid is another publicly funded program (albeit partly by the federal government this time). In fact, taxpayers might have to pay more because the exacerbation of health issues due to lack of care in jail or prison often makes treatment more “more expensive” later. So why does privatization through capitation persist? Perhaps it’s a good way to states to avoid political accountability since having the federal government help pay for healthcare gives the impression that the state governments are being more fiscally responsible even if taxpayers themselves aren’t saving much.

Capitation has contributed to immense success for these private carceral healthcare corporations, with total national revenue for provider companies estimated to be around $4 billion a year in recent years. However, in an apparent race-to-the-bottom for healthcare costs and quality, this substantial income often motivates companies to get even more frugal to make sure they don’t lose out on this revenue. The aforementioned bidding process appears to encourage private companies themselves to aggressively compete against one another in terms of internal cost-cutting to get those coveted government contracts by appearing as cheap as possible to prospective clients. In 2011, one of Corizon’s predecessors managing carceral healthcare for the Chatham County Detention Center in Georgia, Prison Health Services, spent approximately $113,000 per month on sending inmates in need to the hospital for medical care. In 2012, when Corizon won that contract, they cut such costs by 53%. This not only made them look more economical and attractive to future clients, but it also helped augment Corizon’s profit margins for that facility from 14.6% in 2011 to 24.2% in 2013, a sizable increase in net income considering that Corizon is trying to similarly boost profits across all its operations in this multi-billion dollar industry.

Matthew Loflin died from a cardiac-related medical emergency in Georgia after Corizon senior management at the Chatham County Detention Center initially opposed his transfer to a hospital. Three medical staff who tried to hospitalize him as soon as possible later “accused Corizon of prioritizing profits over lives.”

Contributing to incidents nationwide like the one that claimed Wade Jones’s life, cheaper, less qualified staff are among the negative consequences of slanted cost-benefit analyses in favor of financial efficiency over inmate wellbeing. In Alabama for instance, a 2012 state Department of Corrections “Request for Proposal” for new healthcare contracts scored competing bids on a 3,000 point scale. The price that a bid would cost the state was weighed at 1,350 points, while relevant qualifications and experience were weighed at only 100 points. A former mental healthcare professional who worked in the prison system in California, and wishes to remain anonymous (from here on known as Ashley), has recounted how some of her privately contracted colleagues were often hired in with less relevant experience and qualifications than she had. Many private prison employees had “less of an idea of… what they were getting into” and this contributed to them being overwhelmed, or simply unprepared, to address their professional duties. Like Cross, Ashley also blames harmful cost-cutting incentives, stating that the “state [prison] bureaucracy is incapable of caring” for inmates more than finances.

“state [prison] bureaucracy is incapable of caring” for inmates more than finances.

Ashley worked for the state of California, not for a private company. While carceral healthcare run by the government is far from ideal, a significant amount of academic research has indicated that public healthcare can often be better for inmates than private healthcare and that many of the healthcare issues facing inmates today were exacerbated by privatization. Take Arizona for example. In 2012, the state switched from a government-operated carceral medical system to a private system (where Corizon was one of the contractors) in order to save money. Since then, expert witnesses for a class action lawsuit concerning inadequate care relating to undiagnosed illnesses, poorly treated chronic conditions, and more, testified that conditions may have worsened soon after private companies took over. The number of carceral medical employees decreased by 11% from 2012 to 2019, leaving facilities with healthcare staff populations hundreds fewer than what was necessary. The prioritization of profit and cost-cutting has again been cited as a significant factor in such decline. Corizon, Centurion, and other private companies in Arizona operate on a similar capitated basis as was the case in Michigan, so the malignant presence of perverse incentives to skimp on diligent care to minimize expenses looms large. According to Michele Deitch, a faculty member at the University of Texas at Austin Law School who commented on the state of Arizona prisons, “there are questions about whether private health care [is] capable of providing appropriate services, given that the profit motive is going to interfere with the provision of care.”

Dustin Brislan, a plaintiff in a lawsuit against prison healthcare companies and the Arizona Department of Corrections, who alleged that doctors changed his anti-psychotic medication to save money, which nearly led to his death by self-injury. Source: The Marshall Project (Courtesy of the Brislan Family)

In addition to profiteering, oppressive legislation is also another impediment to properly disrupting these companies’ business models. The 1996 Prison Litigation Reform Act (PLRA) makes it significantly harder for current inmates to file lawsuits in federal court for improper care by, among other obstacles, requiring inmates to exhaust all administrative grievance procedures. If these administrative remedies have not been exhausted, then the legal counsel representing the healthcare companies can get these suits dismissed. This makes it very difficult for many inmates, without proper legal support of their own, to get any help from the judicial system unless they have phenomenal skills at prison administrative law, which is often not the case.

“there are questions about whether private health care [is] capable of providing appropriate services, given that the profit motive is going to interfere with the provision of care.”

For those who do eventually succeed at getting a lawsuit off the ground, usually former inmates no longer covered by the PLRA, their struggles are far from over. According to Cross, who is currently suing Corizon, lawyers for Corizon and other private healthcare providers frequently take advantage of existing procedural obstacles for low-income plaintiffs and “never settle, regardless of whether they are at fault or not” until the “eve of trial,” if they choose to settle at all. This can substantially elongate litigation timelines, driving up costs in the process, which in turn discourages legal action for plaintiffs who often don’t have the wealth to finance a protracted court battle. Few victims and their families have access to high-powered plaintiff’s lawyers like Wade Jones’s did. While Corizon and companies like it may have been sued many times, Cross believes that the final number of lawsuits that make it to the stage where these companies might have to pay money damages is so low that it makes little impact on the cost-benefit analysis that informs privatized carceral healthcare contracting. In other words, it is often cheaper for these companies to face lawsuits than to provide adequate care. Therefore, the status quo of inadequate healthcare and its risks, ranging from untreated chronic ailments to outright life-threatening emergencies, can continue relatively unimpeded. Wyoming’s perception of professional effectiveness does not seem so ironic anymore. It apparently does not really matter how well a private prison healthcare provider does their job. As long as they can be cheap for governments, and can bog down meaningful attempts for accountability, they can keep doing what they are doing.

Corizon is far from alone when it comes to perpetuating this inhumane system. Just because one private company loses a contract for negligence, malpractice, or any other reason is no cause for celebration, another company will likely just take its place. The company that succeeded Corizon in much of Michigan, Wellpath (one of Corizon’s largest competitors), is another multistate corporation with another problematic track record on inmate care. According to Stephanie Perez, a third-year law student and a student attorney for the Harvard Prison Legal Assistance Project (PLAP), Wellpath’s mental healthcare practices in Massachusetts prisons are concerning. One of her clients had a mental health crisis while in custody within a facility using Wellpath’s services and “nobody knew how to handle” the matter effectively. Her client spent at least 51 days in isolation for observation within the facility, a process once supported by the Massachusetts Department of Corrections and known as “mental health watch.” Ms. Perez described mental health watch as something that “wasn’t helpful” and may have worsened her client’s mental health. Just like Cross and Ashley, Ms. Perez attributes at least part of the blame for poor private healthcare practices in prison to questionable public sector oversight, stating that regulatory oversight “doesn’t have to be very good,” so it often is not.

It apparently does not really matter how well a private prison healthcare provider does their job. As long as they can be cheap for governments, and can bog down meaningful attempts for accountability, they can keep doing what they are doing.

Mental health watch was alleged to be unconstitutional last year by the US Department of Justice, and a settlement agreement compels the Massachusetts Department of Corrections to “improve policies and training related to mental health care for incarcerated individuals.” Staff are now expected to make regular contact with inmates suffering from mental health issues, not isolate them. However, while progress is being made, when all reforms will be fully implemented is unclear.

What can be done about the issue of private carceral healthcare? The stories out of Arizona, Michigan, and so many other states indicate that cost cutting and profit seeking present substantial obstacles to reform. Meanwhile, what is happening with Massachusetts, and the PLRA, demonstrate that many governments, oftentimes relating to an interest to protect their low-cost private contracting opportunities, implement or endorse regulatory schemes that harm inmates further and/or erect barriers to accountability. According to Lucy Litt, a former inmate welfare advocate with Just Detention International, a guiding principle for any solution here should be to “rais[e] public awareness” so that voters can find out what exactly their elected officials are up to when they act to save money on corrections. After all, these politicians are elected by the public and help fund and otherwise control the apathetic bureaucracies in the first place. Indeed, advocacy groups like the Brennan Center for Justice favor regulatory oversight of incarceration policies, in addition to law enforcement oversight like what the DOJ did with mental healthcare in Massachusetts, to increase accountability via heightening “external scrutiny” and attracting “legislative attention” to inmate rights abuses.

However, others are more skeptical of increased regulation. Ashley thought that increased administration and regulation often caused administrators to worry more about liability and “lose sight of” the personal aspects of caring for inmates by prioritizing strict adherence to quantitative policy requirements to preclude future liability. Instead, she wants to see a fundamental change in the attitudes displayed towards incarcerated individuals. Ashley treated her patients with unconditional positive regard and worked on their behalf to create the feeling that “the world is a safer place.” She does not think that that positive sentiment is anywhere near as common as it should be in carceral healthcare, public or private. Perez seems to agree; staff may “wait a really long time” before giving care to inmates in need because they think that an inmate might be lying to get special treatment. Clearly, changing attributional biases and reducing the prevalence of dehumanizing suspicion may be vital in achieving much-needed reform. However, this is easier said than done, and everyone seems to acknowledge that the specifics of how to accomplish such perception changes are far from clear.

Photograph of J. Myron Thompson. Source: Jackson Free Press

Another option for reform and rebuking the cost-cutting, profit-first narrative is injunctive relief, or having a judge issue an order during litigation mandating that private carceral healthcare providers improve their policies and practices. A recent example of this came from the federal lawsuit Braggs v. Dunn, litigated between the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) (and other public interest legal organizations representing many plaintiffs) and the Alabama Department of Corrections (ADOC). Filed in 2014, this was yet another lawsuit involving neglect so egregious that the 8th Amendment was implicated. The case concerned many systemic/widespread failures in both physical and mental healthcare. At that time, Corizon was contracted by ADOC to provide physical healthcare, and MHM Correctional Services provided mental healthcare. During April 2014, 2,280 ADOC inmates had been diagnosed with hepatitis C; only seven were receiving treatment. The SPLC has reported that, while ADOC has a “policy and practice of not treating” the condition, ”many incarcerated people in Alabama have died of complications from hepatitis C.” Similar to what went on under Wellpath’s care in Massachusetts, according to the SPLC, “severely mentally ill prisoners [were] housed in solitary confinement” with little treatment. Some of the prisoners committed suicide while under this solitary confinement.

![[F]law School Episode 10: Mass Incarceration, Inc.](https://theflaw.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/RICHARDS_PHOTO_Protest2-640x427.png)