20-Packs of Interviews

How BigLaw Pays for Earlier and Earlier Access to Harvard Students

Samara Trilling

July 24, 2024

My aunt Meredith recalls walking into her first day of 1L at Harvard Law School in September 1979 and seeing students wearing suits. She asked one student why. Was he solemnizing his first day with formal fashion? No, the student said. “I’ve got an interview with a firm today.”

This was the first day of 1L. The firm didn’t care if this student knew anything about the law; they just knew he went to Harvard, and were willing to offer him a job on his first day of law school. The race to recruit had begun.

In the 1950s, law students got jobs at the end of 3L year. But the 1960s brought new popularity to the legal profession, and law firms started recruiting before graduation to nab the best talent. When my aunt began law school in 1979, the National Association of Law Placement, or NALP, had just promulgated their first “Principles and Standards for Law Placement and Recruitment Activities” outlining voluntary guidelines for when large law firms (collectively and colloquially known as Biglaw) could begin recruiting students.

NALP began working on guidelines including “a statement of ethics for students and employers” in 1975.

NALP, an association of law school career offices and law firms who purchase membership so they can recruit from the law schools, had been founded eight years earlier in 1971 “during a period of rapid change in both the legal profession and legal education, in response to a perceived need by many law schools and legal employers for a common forum to discuss issues involving placement and recruitment.” NALP’s board pulled together law school administrators (the current board boasts representatives from Penn, UC Davis, William and Mary, University of Georgia and a half dozen other law schools) and representatives from the largest Biglaw firms in the country (including Jenner & Block, Sullivan & Cromwell, Latham and Watkins) to coordinate recruitment

NALP promulgated the first version of the Principles and Standards for Law Placement and Recruitment Activities in 1979.

In 1979, NALP’s recruiting standards hadn’t been widely adopted yet, but they would soon effectively govern the entry-level job application process for most American law students. Over the following decades, member law schools began enforcing the recruitment guidelines, establishing a shared schedule that helped mitigate the problems of so-called “pre-cruiting”: beginning the interview process before the school’s official on-campus interview program.

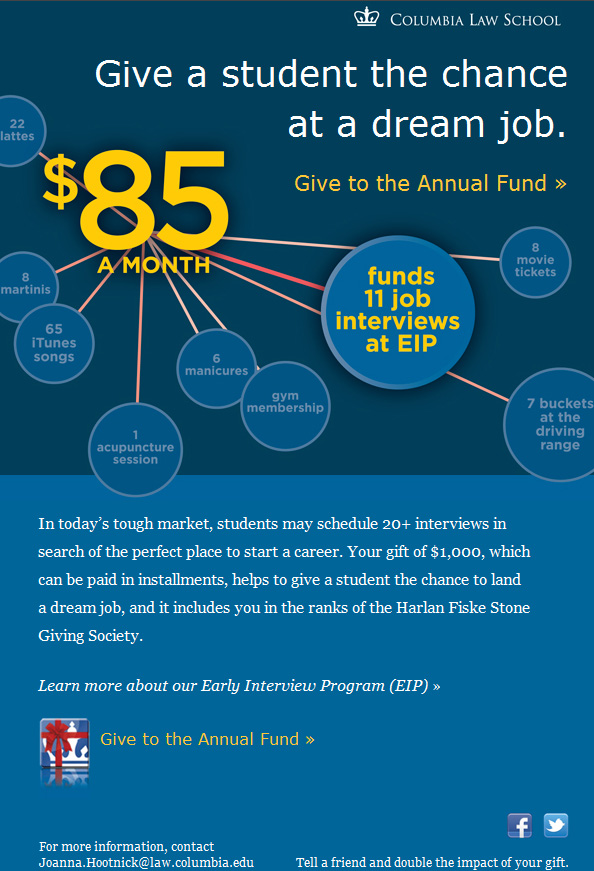

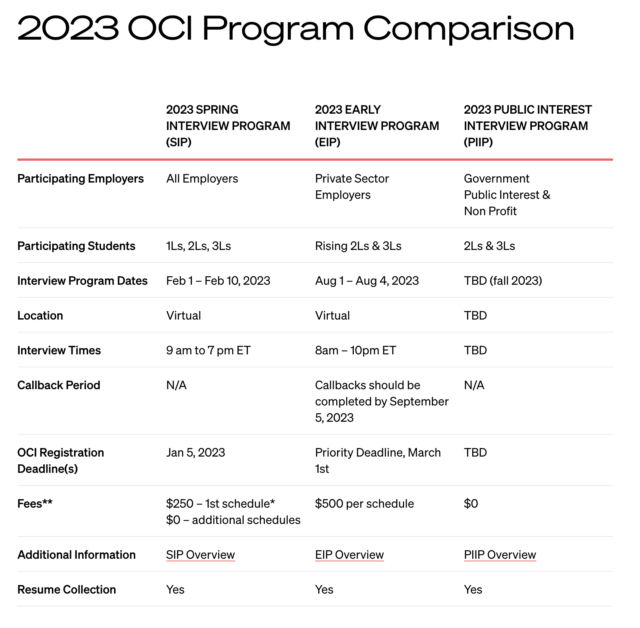

Under NALP guidelines, 1Ls were not allowed to begin career advising until October 15 of their first year, and Biglaw firms couldn’t start recruiting until December 1. Harvard’s Office of Career Services (OCS) centralized most Biglaw interviewing in a three-day interview marathon in the early fall of 2L year, called Early Interview Program, or EIP, as did many other schools (though other schools called their program OCI, On Campus Interviews).

EIP is structured similarly to fraternity and sorority recruitment. Students participate in multiple interview rounds, after which hopefuls submit their bids and firms decide who will make it to the next round. It’s always a stressful time, but NALP’s centralization of the process calmed competition amongst law schools and employers, allowing students to focus on their studies instead of interviewing during class time, and protecting students from feeling the crush of Biglaw interest before they had even decided what kind of law they wanted to practice.

students will again confront pressure to join law firms before their law careers have even really begun

However, after years of a roughly stable detente under these common-sense rules, NALP officially withdrew its guidance in 2018 and abandoned the field entirely to free competition in 2023, citing litigation risk from antitrust rules. In the coming years, students will again confront pressure to join law firms before their law careers have even really begun.

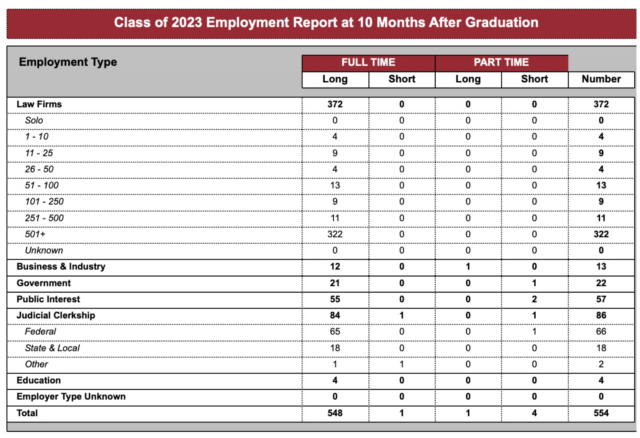

And while individual OCS staffers work hard to make sure students reach their own goals and get the career outcome they want, the school is also subject to structural incentives under which law firms purchase access to law students during EIP, paying Harvard based on the number of students the firm gets to interview. If the fees exceed EIP costs, this dynamic could create a profit motive for the school to encourage more students to do EIP and to do more interviews within EIP. The more EIP interviews with Harvard students firms buy, the more fees Harvard collects.

This combination of ever-earlier interview timing and Harvard’s reliance on law firms for financial support makes it increasingly difficult for students to make free and reasoned choices about their careers after law school. And if any law firm with enough resources can begin recruiting whenever it wants, it’s unclear whether a centralized EIP would continue to have value. The “new EIP” might once again become the first day of 1L.

Competition Unleashed

Harvard’s EIP used to be in September, just as 2L year began. Firms would send “screener” interviewers to Harvard during the first month of school, and fly students to their offices for interviews in October. Other schools had earlier dates, but Harvard’s prestige helped it stay above the competitive fray: firms usually held spots open for Harvard students. This privilege ended with the financial crisis in 2008, when Lehman Brothers collapsed in September right before EIP was due to start. There was a 20 percent drop in the number of law firms participating in EIP. Schools with earlier EIPs could keep the offers they had, but the spots usually held open for Harvard disappeared. Although postgrad employment rates generally remained high, Harvard didn’t want to take any chances the next year. The school moved up its EIP dates in 2009 (to August 24-28) and again in 2011 (to August 15-19) to match other schools’ and avoid being the odd school out.

NALP’s 2018 withdrawal of its guidance didn’t come out of nowhere. With no enforcement mechanisms attached to the guidelines even while they were in place, firms and law schools sometimes cheated the rules. Schools allowed pre-cruiting to get their students early access to Biglaw summer associate spots before they filled up, and law firms competed to recruit earlier so they could get their first pick of students.

Law-abiding law schools had little recourse. They could ban cheating firms from EIP to deprive them of the logistical benefits of a consolidated interview process, but the biggest law firms had enough resources to coordinate their own logistics. And banning firms from EIP would simply exempt them from the consolidated interview scheduling, leaving students on their own while juggling competing job offers and deadlines.

But it was antitrust concerns that NALP cited in 2018 when it removed even the nominal remaining bulwarks against Biglaw pressure. NALP, the argument goes, is a trade association of law firms that compete with each other for talent. If NALP members all agree not to compete for students until a certain date, that’s collusion. The shared schedule prevents law firms from competing with each other on salient employment features, like how early the firm is willing to make offers to students.

![NALP’s website says it “retire[d]” the Principles and Standards for Law Placement and Recruiting Activities, including the “Timing Guidelines,” in 2018.](https://theflaw.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/IT3-2018-NALP-retires-its-guidelines-960x884.png)

NALP’s website says it “retire[d]” the Principles and Standards for Law Placement and Recruiting Activities, including the “Timing Guidelines,” in 2018.

With the guidelines abolished and competition unleashed, Harvard, NYU and Columbia created EIP Preview, an even earlier program that allows students to apply to five law firms in June.

In 2023, NALP acknowledged that law schools, feeling squeezed into moving EIP earlier each year to compete with other schools for Biglaw spots, kept requesting a reinstatement of the guidelines. But, NALP said, “we cannot provide unilateral direction on this issue.” Nor can law schools agree amongst themselves to stop jockeying for position. “We would also caution members that working among themselves to try to limit pre‐OCI recruiting activities could similarly raise antitrust risks.”

A Race to the Bottom

There are now no externally-imposed restrictions on how early law firms can reach out to students. Each school gets to set their own guidelines, with the knowledge that other schools could easily swoop in earlier and take spots from their students. For now, Harvard maintains a unilateral recruiting policy that forbids firms from contacting 1Ls before November 15 and from accepting 1L applications until December 1, but it’s unclear how much longer this will be tenable. Meanwhile, EIP continues to move earlier. In 2024, Preview will begin in mid-June and EIP will happen from July 30-August 1. Stanford and Yale already do their OCI in June, before students have even received their 1L grades.

No one likes this state of affairs. It’s stressful for students to finish 1L finals and immediately begin postgrad recruiting. Earlier EIP means counselors at OCS and its public interest counterpart, the Office of Public Interest Advising (OPIA), have to juggle inquiries from frantic 3Ls about to graduate with anxious 1Ls unsure about their direction at the same time. One Harvard administrator described EIP schedule creep as the thing that keeps them up at night. Law firms generally dislike the early dates, because it requires them to commit to staffing needs sometimes three years in advance. “The fact that it has become this terrible race to the bottom in terms of who can go earliest is good for no one,” said a former HLS administrator.

“The fact that it has become this terrible race to the bottom in terms of who can go earliest is good for no one.”

But it’s a collective action problem: if any one law firm tries to buck the trend and begin recruiting later, they risk losing top students who already have jobs elsewhere. Similarly, if any one school tried to delay Biglaw recruitment, they’d risk all the associate spots being taken by students from schools with earlier recruitment. And if schools tried to end the madness by agreeing on a date to begin recruiting, they’d risk antitrust legal action being brought against them as an illegal cartel — at least according to NALP. As a result, students feel increasing pressure to make a decision about their post-law school careers before they’ve even taken law school classes of their own choosing, which only begin in the second semester of 1L. This virtually eliminates even the illusion of career choice for students, which Harvard insists it protects, a dynamic well-documented in previous issues of The [F]law.

![[F]law School Episode 8: Selling Harvard Law Students](https://theflaw.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/Screenshot-2024-09-08-at-9.59.54 AM-640x427.png)