But priceless experiences obviously do not pay the bills. Fortunately, in recent years, a select few law schools have started programs that help fund students’ summer employment in public interest work. Over 25 years ago, HLS started the Summer Public Interest Funding (SPIF) program under the tenure of Alexis Shabecoff, then Assistant Dean for Public Service. In an interview, Shabecoff explained that with guaranteed funding under SPIF, HLS students are significantly less burdened when pursuing summer internships compared to other law students. This past summer, 56% of first year HLS students relied on SPIF to help fund a summer public interest internship. Various law schools have too since attempted to duplicate the SPIF model to fund public interest students’ summer work.

Nevertheless, even for those receiving at least $20,500 in financial aid, SPIF’s funding is capped at $9,000 for twelve weeks of summer work, and the grant maxes out at $4,200 for students not receiving aid, like the 30% of those that participated in the program in 2023. Notably, many internships require relocation, travel, and other expenses, meaning school summer funding frequently fails to allow students to fully make ends meet while pursuing public interest work. 54% of respondents in an informal survey reported that financial stipends were insufficient and they had to rely on other sources for financial assistance.

As students fight for the chance to toil away at a summer internship while not being compensated by their employer, they quickly internalize that public interest work is not a financially viable career path.

Unpaid and insufficiently funded internships perpetuate inequalities and privilege by gatekeeping seemingly necessary career experiences. Shabecoff acknowledges that even the proliferation of programs like SPIF disincentivizes public interest employers from paying students, instead relying on law schools to pick up the tab. However, this disadvantages students at non-elite law schools that do not have the ability to fund summer employment, closing off many opportunities for public interest minded students. Shabecoff describes, “So now there are [students at] fancy schools that can afford to volunteer and [students at] unfancy [schools] that can’t because they don’t have guaranteed summer funding.”

As students fight for the chance to toil away at a summer internship while not being compensated by their employer, they quickly internalize that public interest work is not a financially viable career path. While the empirics and data on the finances of an actual postgraduate public interest job prove that this is simply not true, the push away from public interest begins in law school where this message is propagated through the cold indifference of unpaid internships. Whether by virtue of not attending an elite law school that can partially fund a summer job, or simply because they cannot stretch limited funding to cover an expensive summer of volunteering, many students face a reality where unpaid summer internships are the first impassable obstacle on their way to a career in public service.

4. The True Price of Service

In addition to the finances, another factor that pushes law students away from public interest is the chronic perception that finding a public interest job is time consuming, rife with uncertainty, and arduous. Alas, this insight is not entirely unfounded. Even if a student who is interested in public interest law is able to get past the difficulties of the unpaid internship, little is guaranteed in terms of future job prospects. For example, while nearly 75% of college students who completed paid internships in the private sector got job offers before graduation, less than 45% of their unpaid counterparts secured employment. Many students at even elite law schools believe that the path to public interest is a competitive and unreliable one, with some comparing it to wanting to become a professional sports player.

Whereas on campus recruiting for Big Law firms at law schools across the country offers students a centralized, streamlined, and exceedingly early path to a summer internship and future career in corporate law, no such experience in public interest compares. Big Law recruiting typically consists of students interviewing with numerous firms in a single week, emerging from the university organized programing with job offers in hand. For HLS’ recruiting week, the Early Interview Program (EIP), students do not even need to submit cover letters and firms will not see their grades before interviews.

HLS Early Interview Program firm sponsors poster. Source: Harvard Law School Office of Career Services Facebook.

On the other hand, public interest students are told to expect months of waiting, numerous rejections, and a general disorganization in their pursuit of a career. Even the valiant attempt of HLS to recreate Big Law on-campus recruiting with V-PIIP has faced struggles. For example, I first sent in my application materials to public interest employers through V-PIIP in August. Presently, over four months later, after multiple ghostings and countless pushed back timelines, I am still waiting to hear back from potential employers I interviewed with and to accept a job offer.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the culture and rhetoric around the public interest job search matches this difficulty with an unwelcoming and unnecessarily exclusionary ethos. Public interest students are repeatedly told that their “commitment” is paramount and will be frequently tested throughout their application process. Students are warned that taking internships at large firms can damage their resumes and that employers are weeding students out in search of “true believers.” As a student interested in public defense, I have been told on multiple occasions that even past work experience in a prosecutor’s office could lead me to being “black-listed” from potential employers. Students interested in public interest careers can expect to go through multiple rounds of interviews and are warned of the regularly combative nature of questioning, often labeled “hostile interviews,” where allegedly the wheat is separated from the chaff. Through this messaging, students adopt the belief that public interest work is indeed only for the select few.

One major driver of this public interest culture comes from the “eliticization” of various public interest careers. As the public interest employment space has struggled to replicate the efficient Big Law recruitment model, it has unfortunately begun to mimic Big Law’s toxic culture of exclusion and prestige. In conjunction with the financial privilege that is maximized through unpaid internships, multiple public interest organizations have started marketing themselves as hyper-elite institutions reserved for the select few.

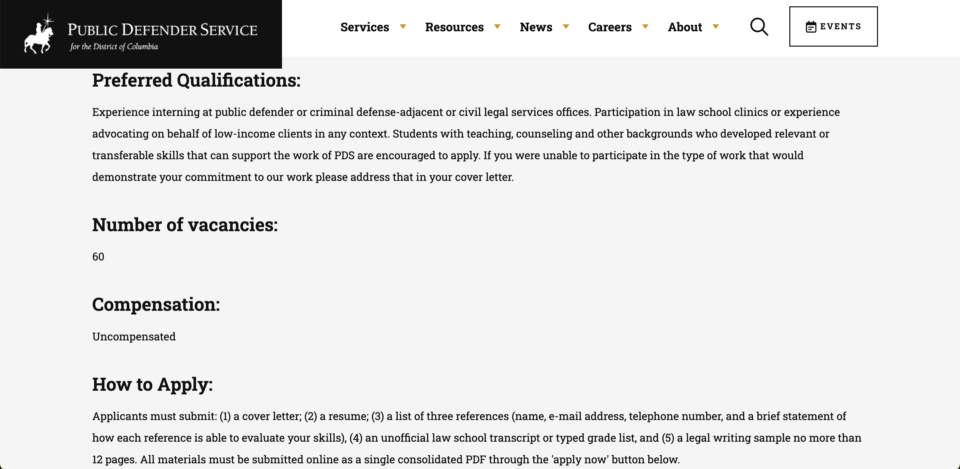

For example, prestigious public interest organizations ask applicants interested in their unpaid internship to submit a resume, cover letter, transcript, references, legal writing sample, and show relevant past experience that demonstrates their commitment. Some employers even leverage prestige to force students into difficult decisions, like choosing between a paid internship, or having a say in assigned office location in exchange for an unpaid position.

Unpaid summer internship job posting for a prestigious public defender’s office. Source: Public Defender Service for the District of Columbia website.

Of course, there are certainly various public interest jobs available to students, perhaps not all at “prestigious” organizations or in geographic markets that elite students prioritize. Mere comparisons to other law schools show that HLS’ flagging public interest numbers are not indicative of a job supply problem. 37% of non-clerking Class of 2015 Northeastern graduates took up public interest employment and a whopping 75% of CUNY graduates pursued those careers. Davis summarized in an interview, “they always say, there’s the scarcity of public interest jobs…but like there’s a scarcity of elite, prestigious public interest and elite prestige is a mirage. It’s a lie.”

Nonetheless, at places like HLS, the public interest legal field has fallen into the same exclusionary prestige trap that Big Law firms represent, but all without the pull incentives a private career can compensate for. Centering public interest hiring around the reputation of an employer or the law school standing of its applicants not only cuts out many who might otherwise make dedicated public servants, but also clearly distorts the motivations of the work in the first place.

Of course, it is worth noting that public interest work is undeniably taxing and difficult work. Public interest attorneys are often overworked, experience vicarious trauma through the emotionally taxing client work they perform, and seem to be disproportionately affected by burnout. Given these facts, it is understandable that a potential public interest employer would want to interrogate potential lawyers as to their level of commitment and ability to stay the course.

At places like HLS, the public interest legal field has fallen into the same exclusionary prestige trap that Big Law firms represent, but all without the pull incentives a private career can compensate for. Centering public interest hiring around the reputation of an employer or the law school standing of its applicants not only cuts out many who might otherwise make dedicated public servants, but also clearly distorts the motivations of the work in the first place.

Yet, is an extended application process or even a tough grilling during an interview the best way to test for commitment to the cause? Perhaps a student slogging through an arduous application process or even their willingness to accept an unpaid internship in the first place is the best and only evidence of dedication that an employer should need. For students who have never experienced such work before, an internship might be their only opportunity to interact with vulnerable clients, an opportunity that might be invaluable regardless of their future career path.

Davis argues that public interest jobs could benefit from doing more “moral formation.” Instead of attempting to divine the students with bonafide commitments to the work, organizations could be honest with applicants about the difficulties of the career path, but still meet them halfway and assist interested students in transforming themselves into the type of passionate lawyers they so desire to be. “The most important thing is…your commitment to the future work, not your past.” Davis concludes that the single worst line during his time at HLS came during the first week of law school when students were told that it was the “saints” of the class that did public interest. But this message that “morally radical people are the only people that do public interest” is simply not true. Requiring such unflinching dedication from inexperienced students is not only an unrealistic charade, but also generates an unhelpful stigma around the work.

The public interest field must recognize its own complicit part in pushing law students away. Admittedly, securing multiple paid internships from one week of centralized interviewing and then having a job offer over a year in advance from a Big Law firm is luxurious. But for the large proportion of students who enter law school passionate about public interest, this might not be all they care about or are influenced by. Far more of a turn-off comes from months of unanswered emails and unrealistic commitment expectations that push students away from their aspirations of service. After a point, regardless of the allure of the Big Law recruitment process, an onerous public interest hiring system becomes prohibitive for all but the most passionate and privileged.

This does not have to be the case, as Shabecoff explains that public interest jobs could do better about managing the recruitment process. While for many public interest employers anticipating hiring needs is difficult, others have well documented lawyer attrition rates and could accordingly hire on a more stable timeline. Furthermore, unpaid internships are definitionally budget independent and hiring could be organized into a more reliable system. Other features like responsiveness and recruitment culture might also be less a product of budgetary constraints than victims of deprioritization.

Even once students begin working in a summer internship or postgraduate job, it is essential for employers to continue their dedication to respecting and nurturing those passionately interested in the work they do. Shabecoff points out that yet another deterrent for students who make it this far in their public interest search is poor supervision, feedback, and training. Shabecoff remarks, “even if you’re really really really busy, and a lot of public interest lawyers are really really really busy…it is incumbent upon you to mentor and care for the next generation so that they are good lawyers, so they’re not deterred.”

Giving students the benefit of the doubt when they say they are committed to public interest and then providing them with an enriching and meaningful summer internship may be the best way to foster their commitments and grow them into dedicated and passionate public servants. The impact of the summer internship cannot be understated as McGill finds that students who work in government and public interest jobs after their second year of law school are five times more likely to take a similar job after graduation. Similarly, for students in California, participating in a public interest internship reduced their likelihood of public interest drift by 34 percentage points, the biggest single variable mitigating drift. Such momentous career experiences should be made more accessible, not less.

5. The Institutional Thumb on the Scale

Of course, various structural factors beyond the mere culture and configuration of hiring contribute to the push away from public interest. Beginning the minute 1L students enter the classroom at law schools, they are taught to distance their normative values and passions for justice from the “black letter” of the law. At HLS, a stifling starting course load of 18 credits (the maximum allowable credit load for successive semesters is 16), enforced competition through curves, and a curriculum that focuses on appellate work leave students little time for reflection on why the law is the way it is, and how they can work to make it more just. Law school quickly turns into far more of a game of parroting the right answers and climbing the academic hierarchy than an education in critical and moral reasoning.

Giving students the benefit of the doubt when they say they are committed to public interest and then providing them with an enriching and meaningful summer internship may be the best way to foster their commitments and grow them into dedicated and passionate public servants.

Immediately after this repressive experience of 1L, and crucially before students have any opportunity to explore their actual interest in the law, Big Law recruiting tears through campus. The vast majority of HLS students participate in EIP before their 2L year, where they interview with dozens of corporate employers whose work is discussed in genericized and abstract terms. The pressure to participate in the program is immense as students who do not register have been contacted personally to reconsider. Even HLS’ website on EIP encourages students to, “consider the larger opportunity cost incurred by not participating in EIP.” 76% of students receive at least one summer job offer from the first wave of EIP alone, with many more waking up from the dizzying fog of Big Law recruiting with an internship opportunity that often turns into a return offer after graduation.

Perhaps predictably, no such equal preferential treatment is given for public interest career recruitment. At HLS, public interest advising has had to fight for its place at the table, and constantly faces an uphill institutional battle. While students pursuing Big Law go to the universal “Office of Career Services” (OCS), those wanting a career in public service must seek help from the “Bernard Koteen Office of Public Interest Advising” (OPIA). I myself, once a naïve 1L, wanted resume help for summer job applications and made an appointment with the confusingly named OCS, who once they found out I was interested in public interest, would not answer my questions, and recommended I instead seek the aid of OPIA. In fact, when using the HLS online recruitment platform CSM, when students select from the drop-down menu of interview programs, EIP is literally the default option, while students must scroll to the bottom to access the public interest counterpart V-PIIP.

![[F]law School Episode 8: Selling Harvard Law Students](https://theflaw.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/Screenshot-2024-09-08-at-9.59.54 AM-640x427.png)