In addition to private equity firms benefiting from limited liability corporate protections, there are two more layers of separation between private equity firms and the companies they oversee. Private equity firms oversee legally independent funds that use acquisition vehicles, generally independent corporations, to buy target businesses.

There are about 4,500 private equity firms in the U.S., but there are over 18,000 private equity funds. KKR, for example, has 146 funds, and Carlyle Group has 290. Funds typically “live” for only up to 10 years. Funds are separate legal entities from firms, generally in the form of limited liability companies or a limited partnerships.

Funds differ in size and are responsible for raising capital individually. Smaller, more niche funds set capital goals around $500 million; mega-funds may raise as much as $10 billion. In contrast to publicly traded companies, not just anyone can invest in private equity funds. Firms have different minimums, but on the low end, at least $250,000 is required to invest in a fund. Because bars to entry are so high, most capital is sourced from pension funds, endowments, high net-worth individuals, and sovereign wealth funds. When such entities invest, they become limited partners. The private equity firm and its executives serves as general partners for funds.

Private equity firms oversee legally independent funds that use acquisition vehicles, generally independent corporations, to buy target businesses.

Theoretically, general partners may face personal liability for losses. But in reality, there are layers of legal protections that insulate private equity firms and executives. In particular, firm executives benefit from the use of exculpation and indemnification clauses. Exculpation, under Delaware law, frees corporate directors and officers from facing personal liability if they are found to breached their duty of care. Executives are also generally protected by indemnification agreements with the portfolio company, meaning that the company can be held financially responsible for breaches by firm executives controlling company decisions. As the law firm Proskauer Rose LLP explains, “Typically, the [private equity executive] has indemnity rights on multiple levels, including the portfolio company level, the fund level, and potentially the management company/sponsor level.”

As author Brendan Ballou puts it, the success of a private equity firm “does not always depend on the success of the companies that they own.”

In traditional private ownership contexts, lawsuits and bankruptcy have the potential to significantly affect investors. Even for limited liability corporations, investors stand to lose significant amounts of money invested in the company. Not so for private equity firms that use debt to buy companies, which then goes on the company’s balance sheet. So long as the fund has recouped their initial investment—which can be as low as 10 percent of the overall cost of the buyout—firms don’t lose a penny during bankruptcy. Even when companies are doing very poorly, private equity funds profit from management fees and dividend recapitalizations (i.e. required bonuses paid to the firms regardless of company performance).

As author Brendan Ballou puts it, the success of a private equity firm “does not always depend on the success of the companies that they own.” In part because of the absence of meaningful liability concerns, and also because private equity firms focus on short-term maximization rather than long-term stability, there is often a fundamental misalignment between the priorities of firms and other stakeholders, including the portfolio companies themselves and employees.

The biggest U.S. employers you’ve never heard of

Private equity firms own companies that employ almost 12 million workers in the U.S., in industries ranging from coal and manufacturing to health care and technology. Roark Capital, a private equity firm headquartered in Atlanta and named after the main character in Ayn Rand’s book The Fountainhead, owns companies that employ around 1.4 million people, including Dunkin Donuts, Arby’s, Subway, and other fast-food chains, among other businesses. In comparison, Walmart, the biggest U.S. employer, employs 2.3 million people. On the list of the biggest U.S. employers on the Fortune 500, Roark would land third—right after Amazon and right before FedEx—if employees at the companies it managed were attributable to the firm.

Roark Capital is not the only private equity company that is, in effect, a huge-scale employer. KKR, one of the world’s biggest private equity firms, owns companies that manage over 800,000 people, which would put it fourth on the list of U.S. employers, right after Roark. Carlyle, another firm, owns companies that manage 650,000, and Blackstone 550,000.

Roark Capital owns companies that employ 1.4 million people

Of course, you won’t find any of these firms on the lists of the largest American employers—because based on legal definitions, they aren’t. According to the Cornell Legal Information Institute, “[a]n employer is an individual (a person, company, or organization) that hires another individual (an employee), pays the employee a salary or wage, and has the power to control the employee’s work duties; an individual who employs and supervises an employee.” Unsurprisingly, companies remain independent legal entities when they are acquired by private equity funds. But unlike in other investment contexts, where investors take a more passive role, private equity executives become highly involved in company decisions. Such executives often play key roles in decisions about employment matters.

When a private equity fund buys out a company, the fund generally installs a new board and new management. As one Wharton Business School student studying private equity explained, the firm becomes the “puppet master” behind nearly all of the decisions of the company they acquire. Fortune estimates that in 70 percent of LBOs, the private equity firm installs a new CEO. “New management is installed by the private equity firm, and the new CEO is beholden to the board, which is controlled by the firm. So, the management plan is largely in accordance with the goals of the private equity firm,” he said.

Employment decisions commandeered by the firm do not end with the C-suite. In most LBOs, private equity firms make employment decisions that touch nearly every worker in an effort to increase profit margins. Such decisions can include slashing paid holidays, eliminating employer-match pension programs, changing employees’ insurance plans and benefits, and laying off workers. Studies have shown that employee job satisfaction, work-life balance, and positivity about corporate culture all decline after LBOs. Private equity firms claim that employees benefit from increased opportunities and job prospects, but because most restructuring comes from outside rather than from within, that is generally not the case.

Firm ownership of companies is often intentionally opaque. Roy spoke to this directly, commenting that he and his coworkers “never really knew who the owners were, it was all hidden behind a bunch of companies . . . They did their best to hide all this stuff from us, for what reason I can’t tell you why, but they must have had one.”

This obfuscation was likely a result of a couple things, including shifting management structures after the Generating Station was sold to various private equity firms and the desire to maintain distance from stakeholders due to liability concerns.

Studies have shown that employee job satisfaction, work-life balance, and positivity about corporate culture all decline after leveraged buyouts.

Despite the layers of corporate protection fund executives benefit from, lawyers advising private equity firms are highly cognizant of the need to keep legal distance between private equity executives and the portfolio companies they manage. Dechert LLP writes that private equity firms should make sure that employment decisions “are made in accordance with existing protocols and are well documented” to avoid liability concerns. In other words, at least on paper, private equity executives should maintain arms-length distance from employment decisions. The risk is that the private equity firm would have to undergo “millions of dollars in motion practice, invasive (and, at times, potentially embarrassing) discovery into the relationship between the PE firm and the portfolio company, settlements and judgments,” the website of the law firm Schulte Roth & Zabel writes.

The “puppet master” behind portfolio company decisions

Private equity firms play huge roles in strategic decisions after LBOs, including employment decisions and at times mass lay-offs. But, for the most part, they aren’t legally accountable for such decisions because they aren’t considered workers’ “employer.” Sometimes, they aren’t even considered owners of the company itself.

One distressing example of that is the case of Annie Salley, who was a long-time resident at a ManorCare nursing home in South Carolina. When ManorCare was acquired by Carlyle Group in 2007, it laid off workers and reduced the quality of its services to cut costs. Because of staffing reductions, Salley had to walk to the restroom by herself despite mobility impairments, and in doing so she fell and hit her head. She died of brain bleeding after the nursing home failed to report her fall to a physician. When her family sued Carlyle Group, the case was dismissed. Despite Carlyle being responsible the changes that caused the accident, such as the staffing shortages, and despite the fact that Carlyle was the sole shareholder of the company, Carlyle did not own ManorCare, legally speaking. In the opinion dismissing her claim, Judge David C. Norton stated that “stock ownership is insufficient to confer personal jurisdiction” over a corporate defendant, and that the corporate veil could not be pierced because “this court is not required to draw ‘farfetched inferences’” about why certain corporate decisions were made.

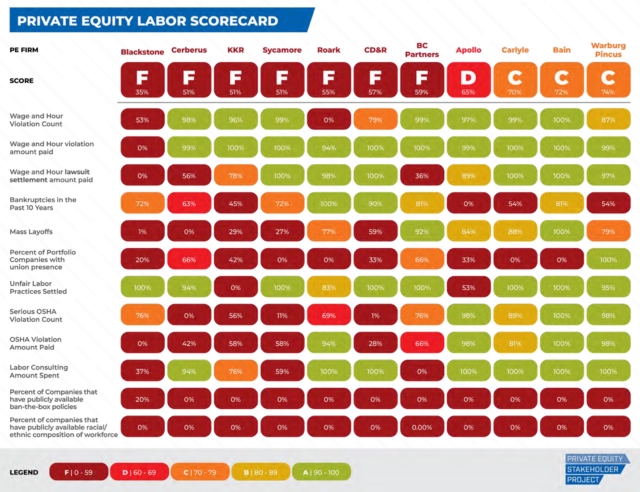

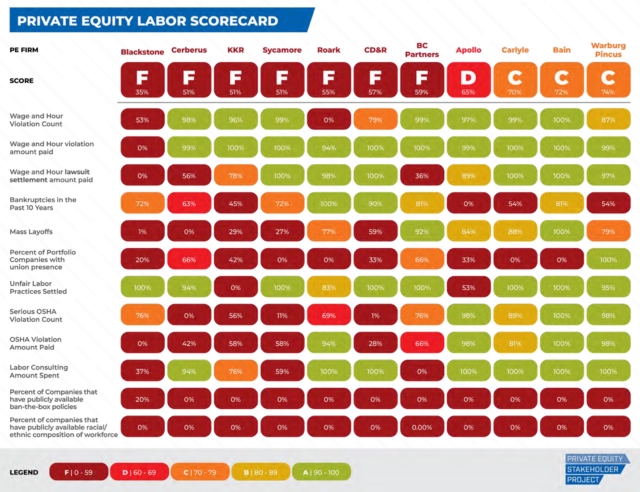

Clients and customers are not the only ones who suffer. For professional corporate problem-solvers, labor and employment law violations by private equity owned companies are shockingly common. In November 2023, the Private Equity Stakeholder Project issued “scorecards” to the largest private equity firms along various labor and employment dimensions, such as wage-and-hour violations, Occupational Safety and Hazard Act (OSHA) violations, number of bankruptcies, and number of portfolio companies with unions. Blackstone, which oversees over $1 trillion in assets and is the largest private equity firm in the world, scored worst amongst peers.

Source: The Private Equity Stakeholder Project

In addition to high rates of wage-and-hour violations, Blackstone was fined $1.5 million by the Department of Labor (DOL) in February 2023 for three years of child labor violations at a meat-packing plant in Wisconsin. The spokesperson for the DOL commented that the violations were a “no clerical error” but rather “a systemic failure” across the portfolio company’s operations. The investigation resulted in a $1.5 million fine for Blackstone’s portfolio company, Packers Sanitation Services Inc. No action was taken directly against Blackstone, and, as the Wall Street Journal reported, Blackstone “faced little public blowback from investors” as a result of the incident.

The declaration of bankruptcy is another tool that can be leveraged against employees by private equity firms. Bankruptcy provides various forms of legal protection for firm, and it allows companies and firms to evade some creditors.

“Employee claims come last during bankruptcies,” stated Steve Churchill, the founder of employee-advocacy law firm Fair Work P.C. and the head of the Employment Law Clinic at Harvard Law School. One former Toys “R” Us employee echoed this sentiment, saying that after the company declared bankruptcy, “[e]mployees were told there’s not enough money left after paying the company’s creditors, bankruptcy attorneys and consultants” for them to get severance pay.

One employment attorney, who spoke on conditions of anonymity, dealt with this directly when he represented a class of former Papa Gino’s pizza delivery drivers. The company had not been paying them for transit costs during deliveries, which under Massachusetts law, was required of the company. While Churchill was preparing to file a class action lawsuit on behalf of the drivers, Papa Gino’s, which had been bought by the private equity firm Wynnchurch Capital, filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy. In other circumstances, that might have been the end of the lawsuit—court permission is often needed to file a civil suit against a company in bankruptcy. But it wasn’t the end of the case here.

Holding the “puppet master” accountable

Using the Massachusetts wage law, the lawyer filed against the principals of the company instead of the company itself. As it so happened, one of the private equity firm’s partners had been appointed to serve as president of the Papa Gino’s corporation, which, due to indemnification provisions, functionally provided a hook for plaintiffs to hold Wynnchurch Capital liable.

On the state level, there are varied standards when it comes to imposing liability on employers. The Massachusetts Wage Act, G.L. c. 149 § 148, states that the president, treasurer, and “any officers or agents having the management of [a] corporation shall be deemed to be the employers of the employees of the corporation.” Other states, such as Nevada and Colorado, have decided that managers and corporate executives cannot be held individually liable for wage violations.

In Massachusetts, the Supreme Judicial Court held that managers of a limited liability company could be held individually liable for state wage law violations. The court noted that “[n]o reasonable legislative purpose would be served by holding ‘any officers or agents having the management of [a] corporation’ accountable for violations of the Wage Act, but not the managers of other limited liability business entities who similarly control policies and practices related to the timely payment of employees.”

Even in a worker-friendly jurisdictions like Massachusetts, though, Professor Steve Churchill explained that it’s incredibly rare for private equity firms to face liability for employment violations. “When employment violations arise at a company managed by a private equity firm. Even if the private equity firm mandated the decision, only the company itself would be financially liable for it.”

In recent years, there have also been attempts at the federal level to hold private equity firms accountable for employment law violations. One of the first opinions that suggested that private equity funds may face some liability for actions of their portfolio companies was an opinion out of the Eastern District of Michigan in 2010. In Board of Trustees, Sheet Metal Workers’ National Pension Fund v. Palladium Equity Partners, the district court held that it was a genuine issue of material fact whether three private equity firms were joint employers and therefore subject to abide by ERISA.

A year later, the Fifth Circuit said in Oaktree Capital Management, L.P. v. National Labor Relations Board that private equity firms may face liability for unfair labor practices under National Labor Relations Act. And in 2013, a Second Circuit panel determined that private equity funds could potentially be held liable for violations of the WARN Act, which requires employers to give employees at least 60 day’s notice before termination. All of these are still relatively open questions. The private equity firms involved likely settled the cases after their initial motions to dismiss were rejected in order to avoid bad case law.

In light of these decisions, one law firm advised its private equity clients to respect “corporate formalities,” warning that if they don’t, “courts likely will look past the company’s separate corporate form and hold deep-pocket investors liable for its employment-related decisions.”

Policymakers are also paying attention. The Biden Administration has launched an inquiry into private equity companies trying to acquire companies in the health care space. And after multiple reports came out about abhorrent standards of care in nursing homes owned by private equity firms, the Biden Administration finalized a rule requiring disclosure of ownership of nursing homes. It has also urged pension funds to divest from private equity funds.

On the legislative side, Senators Elizabeth Warren, Tammy Baldwin, and Ed Markey have been some of private equity’s toughest opponents. But other policymakers, on both side of the aisle, are invested in private equity. Republican Florida Senator Rick Scott is the highest investor in Congress, with $76.5 million in private equity. He’s followed by Senator Mark Warner of Virginia, a Democrat, who has $30.8 million in private equity. Still, there is increased awareness of private equity’s role in our economy and society today than even a couple of years ago.