Though only one of many neighborhoods that have experienced the threat of displacement brought forth by urban renewal, Roxbury represents one of the most significant and radical efforts by a neighborhood to challenge corporate power. Roxbury was one of the first settlements founded by English colonists in the 17th century. Originally an independent city, Roxbury was annexed by Boston in 1868. The neighborhood has historically hosted working-class communities and was a hub for mainly Jewish and Italian immigrants in the late 19th century. During the Great Migration in the early 20th century, thousands of Black Americans from the South re-established themselves in Roxbury to chart new lives in the rapidly industrializing North. Today, Roxbury is known as the “heart of Black culture in Boston.”

In the 1960s and ‘70s the neighborhood became a center for grassroots activism that targeted issues such as land use, education, and unemployment. Land use, however, was especially important to residents due to the large-scale urban renewal projects undertaken by the Boston Redevelopment Authority (BRA), the predecessor of the BPDA and pejoratively called the ‘Boston Removal Authority’ by activists. For example, the agency was responsible for one of America’s largest urban renewal projects, which displaced over 7500 working-class residents from Boston’s West End neighborhood. Homes, schools, and small businesses were demolished to make room for luxury housing, highways, and commercial and government offices. One of Roxbury’s greatest economic resources is land since relatively few open spaces for physical investment remain in the rest of Boston, making the area ripe for urban gentrification. With this history and context in mind, the residents of Roxbury were determined to deter the same fate as their West End neighbors.

Black activists in Boston became increasingly organized in the wave of political activism triggered by the Civil Rights Movement and the deteriorating social and economic situation in their city. After repeated failures by the city government to desegregate the city and the BRA’s unchecked power and expanding reach, Roxbury residents identified Black liberation as the key to ensuring the continuity of their community. Many realized their relationship with the city mirrored the colonial relationship seen in much of the Global South, noting that “the economic relations of the ghetto to white America closely parallel [the relations] between third world nations and the industrially advanced countries.” As such, many activists compared their struggle to the anticolonial struggles of the colonized world. It was at this point the first ruminations of a new city guided by self-determination rose to prominence in the Black communities of Roxbury.

West End Demolition for Urban Renewal: Before and After.

The Greater Roxbury Incorporation Project (GRIP), also known as the Mandela Initiative, organized in the 1980s in response to the city’s role in the destruction of Roxbury. Activists contended that land control was crucial, as “land control is the key to self-determination.” Radical economists argued that “if community control can help poor Blacks empower themselves and alter some of the ‘colonial’ economic mechanisms that marginalize them, then in the long run the community control strategy may offer a great deal of promise for economic development.” Black communities were growing extremely frustrated with their repeated failed attempts to influence local government policy, especially after the failure of Mel King to secure a mayoral election win despite winning the Black vote by nearly 99%. As Byron Rushing, a Black Massachusetts state legislature member, put it, “why should we go out and kill ourselves, marching up and down to register to vote for a mayor of a city which is only 20-25 percent black? Why not break our backs to elect our own Mayor, who would appoint a chief of police…our own city council, instead of using energy to try to be a part of a system with very little sympathy for us; use it [energy] to be independent.”

Andrew Jones and Curtis Davis echoed the state legislature member’s sentiments, stating in their official Greater Roxbury Incorporation that “we have tried every means, except incorporation, to solve our many serious problems. We have been individually and collectively frustrated by not having the internal tools to exterminate the conditions which have blighted our neighborhoods. The time has come for us to assume full legal control over our community. Nothing short of total enfranchisement will do.”

“We have tried every means, except incorporation, to solve our many serious problems. We have been individually and collectively frustrated by not having the internal tools to exterminate the conditions which have blighted our neighborhoods. The time has come for us to assume full legal control over our community. Nothing short of total enfranchisement will do.”

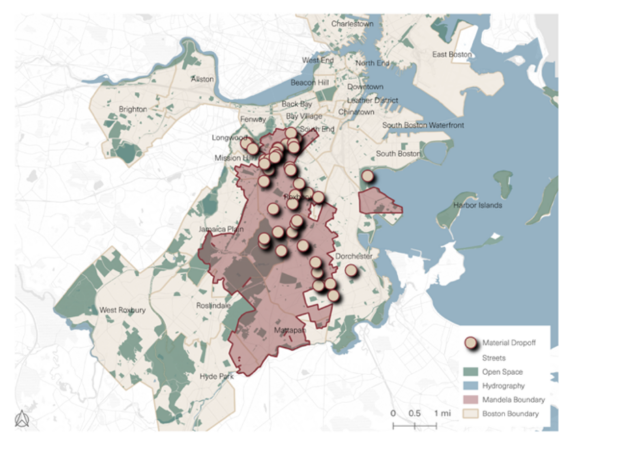

In their plan they set out to separate Roxbury, as well as parts of Dorchester, Mattapan, Jamaica Plain, South End, and Fenway, from Boston and create a new Black-majority municipality to push for more community-control. Here, they argued that “the most meaningful, if not powerful, form of government is local government. Since municipalities have no obligations, except to residents, they are able to focus efforts on internal priorities undiluted by outside interference.” Furthermore, in contrast to the white-dominated Boston, Roxbury’s “residents from all walks of life and every ethnicity” recognize that “the principles of government lie in enfranchisement and not colonization.” Though they recognized that “access/representation is not enough” they contended that “a community must be free to run its own affairs unhindered by outside interests. Government is not a glamorous process. It is the means by which ordinary people make the most out of their sacrifices, their principles.”

They sought to propose a referendum that would call for the legislature to vote on the separation of these neighborhoods. Progressive politicians and Black residents supported the plan enthusiastically in what was seen as a move to redress decades of racist treatment and a shift to a more accountable local government. Opposition to the movement, however, was strong. Critics assailed the project as one that would “re-entrench segregation” and as “counterproductive and polarizing in its attempt to divide Boston,” pejoratively calling the project “Separatist City.”

Establishment media was also harsh. The Boston Globe, in what was described as “near-hysterical outpouring not seen since the 1970s racial violence associated with busing,” ran a sweep of articles charging Mandela advocates with “deceitfulness,” “negativism, untruths, and confusion,” and making “loud, angry charges,” as well as being “hostile and divisive” and “promot[ing] racial segregation.” Non-local newspapers, like the New York Times and The Los Angeles Times also published articles with titles like, “Separatist City of Mandela: Boston Voting to Let Black Area Secede” and “Irate Blacks Pushing for Secession in Boston.” The referendum on GRIP failed to pass after it was brought forth in both 1986 and 1988.

![[F]law School Episode 7: Profit Over People](https://theflaw.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/Housing-Podcast-Episode-hero-image-640x427.webp)