Over Zoom last spring, I asked economist and geographer Silvia Secchi about whether land access is a barrier to entry for young farmers in Iowa. She laughed wryly “It’s a big-ass problem. If you don’t inherit the land, it’s hard to start farming.” Her colleague at the University of Iowa, environmental scientist Chris Jones, jumps in, “Someone right out of college can’t move to Manhattan and buy a house, and someone who wants to start a farm shouldn’t move to Iowa — it’s the Manhattan of farming. I’d love to see more young farmers in Iowa, but people in Hell want ice water, too.” Jones adds, “If your dad or grandfather farms, you ask them to give you five acres, and you put a hog barn on it. That’s your entry point, the livestock industry.”

“I’d love to see more young farmers in Iowa, but people in Hell want ice water, too.”

Iowa, notably, is home to one of the country’s few anti-corporate farming laws, which restricts the ownership of farmland to individuals, or certain types of family-scale LLCs or trusts. Even so, Iowa’s corn and hog-heavy farm economy churns out some of the worst environmental, community, and animal welfare harms in the country. Secchi tells me, “It’s kind of a moot distinction if the ‘non-corporate’ farmers are Tyson contract growers. What does it mean if the farm’s ownership structure is complicated, in an effort to minimize taxes and maximize gains? It means more accountants and lawyers getting involved. How is that not corporate? To me, that’s corporate.”

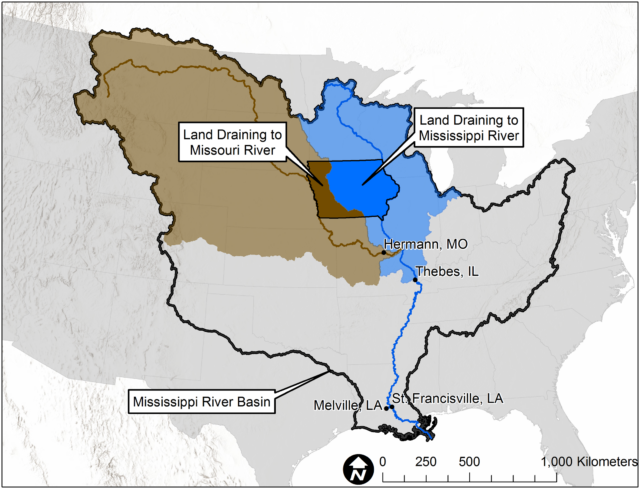

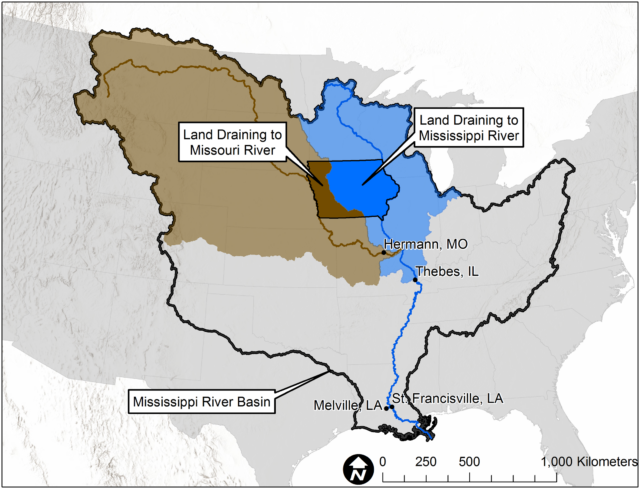

Even with the protection of the anti-corporate farming law, entry-level farmers and sustainable agriculture are effectively shut out of Iowa farming – by the same “family farmers” you may have heard are under threat. “Land is a bank account,” Jones told me bluntly. He studies the devastating effects that Iowa’s brand of family farming — most notably the combination of Iowa’s two biggest commodities, corn and hogs — have on the environment, especially the Mississippi River and Missouri River watersheds. He and Secchi also co-host a podcast, We All Want Clean H20, which explores these impacts and the policies behind them. “There’s more money in agriculture than there’s ever been.” Secchi chimes in.

I had reached out to Jones and Secchi hoping to get their perspective on a phenomenon that had become my latest bugbear – skyrocketing farmland prices, and the growth of farmland as an investment class, especially its increasing popularity among private equity firms, pension funds, and individual high-wealth investors, Bill Gates most famous among them (although investment guru and chairman of Berkshire Hathaway Warren Buffet has long touted farmland investment as part of his “value investing” philosophy).

The data shows a real increase in this type of investment, with particular uptick after the financial crisis of 2008. Between 2010 and 2014, over 100 agriculture and farmland-focused funds closed, directing more than $22 billion in investment capital into the sector. At the same time, a global food crisis caused by drought and other climate-related crop failures drove food prices up; in response to these catalysts, the price of farmland has shot up, climbing from an average price of $2010 per acre in 2007 to $3030 in 2017. Farmland, long considered to be merely a conservative investment backstop, a safe harbor for wealth, has drawn new interest as an investment class that offered significant, reliable gains over a relatively short term.

The price of farmland has shot up, climbing from an average price of $2010 per acre in 2007 to $3030 in 2017

The contemporary wave of farmland investment is led by institutional actors, particularly pension funds (most notably TIAA) and investment-focused subsidiaries of insurance firms like UBS and Prudential. Foreign investment in U.S. farmland has also doubled between 2009 and 2019; foreign holdings of American farmland are currently over 35 million acres. Crowdfunding-style farmland investment platforms have even opened up, granting investors access to a fraction of a farm property at a lower investment threshold. Companies like AcreTrader and FarmFundr offer investment minimums in the low five figures, making direct farmland investments much more accessible for a broader swath of investors.

Both AcreTrader and FarmFundr are founded by farming scions; Carter Malloy of AcreTrader is part of a farming family from Arkansas, while Brandon Silveira comes from “three generations of California farmers.” These platforms advertise accessibility and convenience – for the passive investor. As Malloy explained on the podcast We Study Billionaires, if you’re an average investor who wants to get started in farmland investment:

While investment firms may not be causing the surge in prices, they are certainly finding new ways to profit from it.

“You’ve got to go out to a county you’ve probably never heard of, meet with a broker you certainly never met, pop down a million dollars, oh, and now you get to manage a farm… So on our platform, it’s easy. It takes a few minutes to do it all electronically… We take care of the investment, the management payments, facilitation of leasing, insurance, in the end, we are there to support the investors and farmers both to reduce the load to near zero for those investors.”

In short, while investment firms may not be causing the surge in prices, they are certainly finding new ways to profit from it.

The percentage of American farmland held this way, as a pure investment, is still quite small. However, the sharp and continuous increase in investor ownership of agricultural property has many troubling implications for the American food system and the future sustainability of rural and agricultural economies. My supposition was that this uptick in farmland investment might have something to do with the land access challenges my “right kind of farmers” were facing.

I floated this hypothesis to Nathan Rosenberg, a visiting scholar at Harvard Law School’s Food Law and Policy Clinic, who was skeptical. “These types of corporate investors don’t have as much of an impact on prices as something like the uptick in renewable energy uses. Other factors like crop insurance, other [USDA] subsidies, programs like the Conservation Reserve Program [CRP] – that’s tens of millions of acres that provide very little environmental benefit that farmers are being paid, as a subsidy, not to do anything with.”

Silvia Secchi agreed that USDA subsidy programs help attract savvy investors. “[USDA] subsidies used to be counter-cyclical, but now they’re built so that farmers get them whether the market is high or low. They’re a baked-in component that gets capitalized in the value of the land. There’s no downside risk. Even during the trade wars, soy farmers were given more money than they were losing. This is the set of incentives, plus complete lack of regulation.”

[USDA subsidies] are a baked-in component that gets capitalized in the value of the land. There’s no downside risk.

As Secchi indicated, farmland is an appealing investment for more than just the land’s anticipated appreciation. Agriculture is both propped up by government subsidies and is also among the least regulated industries in the United States; farms are largely exempt from workplace safety regulations, labor relations laws, and environmental laws, for example. These exemptions have allowed agriculture to become the United States’ leading cause of water pollution, a prime source of air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions, and to boast some of the highest rates of workplace injury and death combined with some of the lowest average wages. A complex web of farm labor contracting and a growing reliance on temporary guestworkers or undocumented farm laborers further enables many of the exploitative labor practices that are already widespread in the agricultural industry.

Farms are largely exempt from workplace safety regulations, labor relations laws, and environmental laws

In many ways, buying productive farmland in the United States is comparable to investing in any industrialized manufacturing property – except farm operators don’t have to worry about their employees unionizing; don’t need to filter the pollutants coming out of their smokestacks, and aren’t likely to have OSHA stop by to make sure the dust levels on the factory floor are up to spec. They benefit from lower agricultural tax rates, and ten years down the line, the “factory building” — the farmland itself — will be worth more than it was at the time of the initial investment. And in case that wasn’t a friendly enough proposition, the government will send the “factory” owner a check every year to keep part of the operation shut down, guarantees a fair price for the widgets the “factory” produces, and allows the owner to keep many of their most valuable assets, including the land itself, should the business go bankrupt.

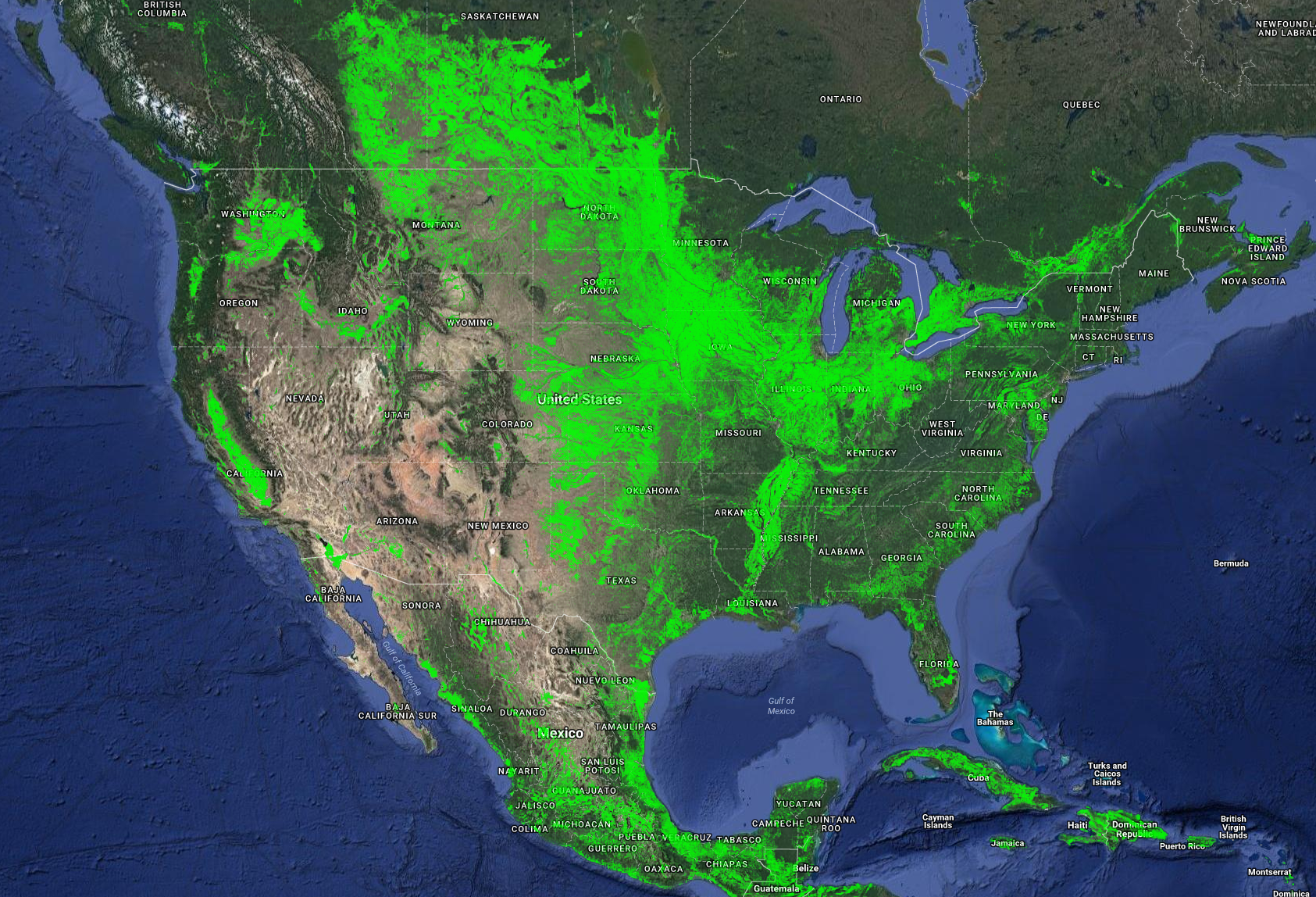

And about those widgets: close to half of the 400 million acres of cropland in the U.S. are devoted to corn or soy; about 90 million to each. Of the corn, about 60% is fed to livestock, and the other 40% is refined into ethanol; almost all the soy goes to livestock feed. As has been well publicized, the U.S. livestock industry is heavily, and increasingly, reliant on Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs), which tend to have a reduced standard of animal welfare, a heavier reliance on antibiotics, and higher outputs of air and water pollution than other methods of livestock production. As for ethanol, new research has come out suggesting that the corn-based fuel is actually more carbon-intensive than traditional gasoline.

__________

The body that is most responsible for the shape of American agricultural policy, and thus American farming, is the United States Department of Agriculture. The USDA was founded in 1862 as the federal agency responsible for conducting agricultural research and education, with the goal of improving the United States’ crop quality and yield. Its mandate was greatly expanded during the New Deal era, with a suite of new nutritional assistance, rural development and farm financing sub-agencies added to help lift the country’s agricultural regions out of crisis.

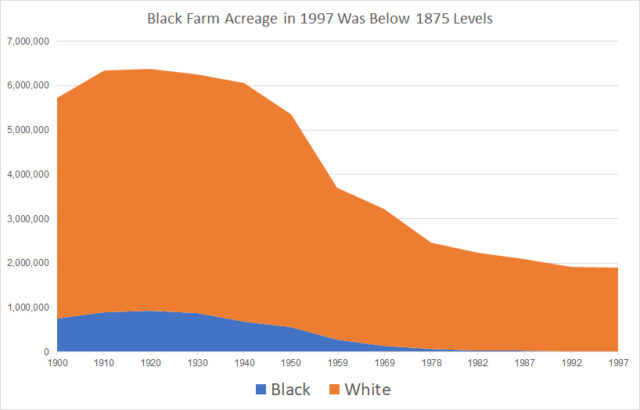

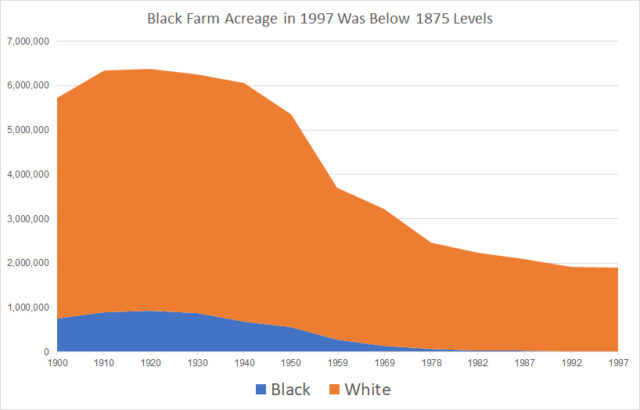

Since its founding, the USDA’s programs have largely perpetuated the United States’ foundational agriculture dynamic of wealthy white landowners profiting from the labor of (disproportionately) Black and brown farmworkers – Jefferson’s idealized “small landholders” were white, of course. The agency has been the subject of several extensive federal civil rights investigations since the middle of the 20th century, each successive report uncovering ongoing widespread, systematic discrimination throughout the agency’s programs. Some critics go so far as to refer to the USDA as “The Last Plantation” for its long history of favoritism toward white farmers to the detriment of Black farmers in particular. Black farmland ownership peaked in the early 1900s; in the hundred years since, Black farmers have lost close to 90% of that acreage, largely as a result of discrimination in USDA lending programs, an estimated loss of hundreds of billions of dollars of wealth.

Chart of 20th century farm ownership courtesy of the Duke World Food Policy Center. See more at wfpc.sanford.duke.edu.

The USDA fulfills the dual mandate of promoting American agricultural products and regulating their producers, and is known to have a revolving door for agribusiness executives. Because of the permeable membrane between agribusiness and the USDA, the agency has long served as an advocate for and ally of agribusiness and industrialized agriculture, an attitude best embodied in Nixon-era Secretary of Agriculture, Earl Butz, who urged farmers to “get big or get out” (perhaps unsurprisingly, Butz resigned after making an incredibly racist joke in front of a reporter). As Secchi told me, “The distribution of wealth that this system of subsidies has created is concentrated in fewer hands – and just like we don’t tax Jeff Bezos, we don’t tax Iowa farmers.”

The agency has long served as an advocate for and ally of agribusiness and industrialized agriculture

In addition to administering the federal crop subsidies Secchi and Rosenberg evoked in our conversations, the USDA’s “conservation” funding largely goes to incentivize taking farmland out of production, updating irrigation systems, and building manure management facilities. These practices often provide some marginal benefit to the environment, but largely serve as a boon to Big Corn and factory-scale animal agriculture. A recent investigation by the nonprofit Environmental Working Group found that only a fraction of the funding for the USDA’s biggest conservation programs goes to support practices that the agency itself has designated “climate smart,” and some of the practices funded by conservation grants actually increase greenhouse gas emissions.

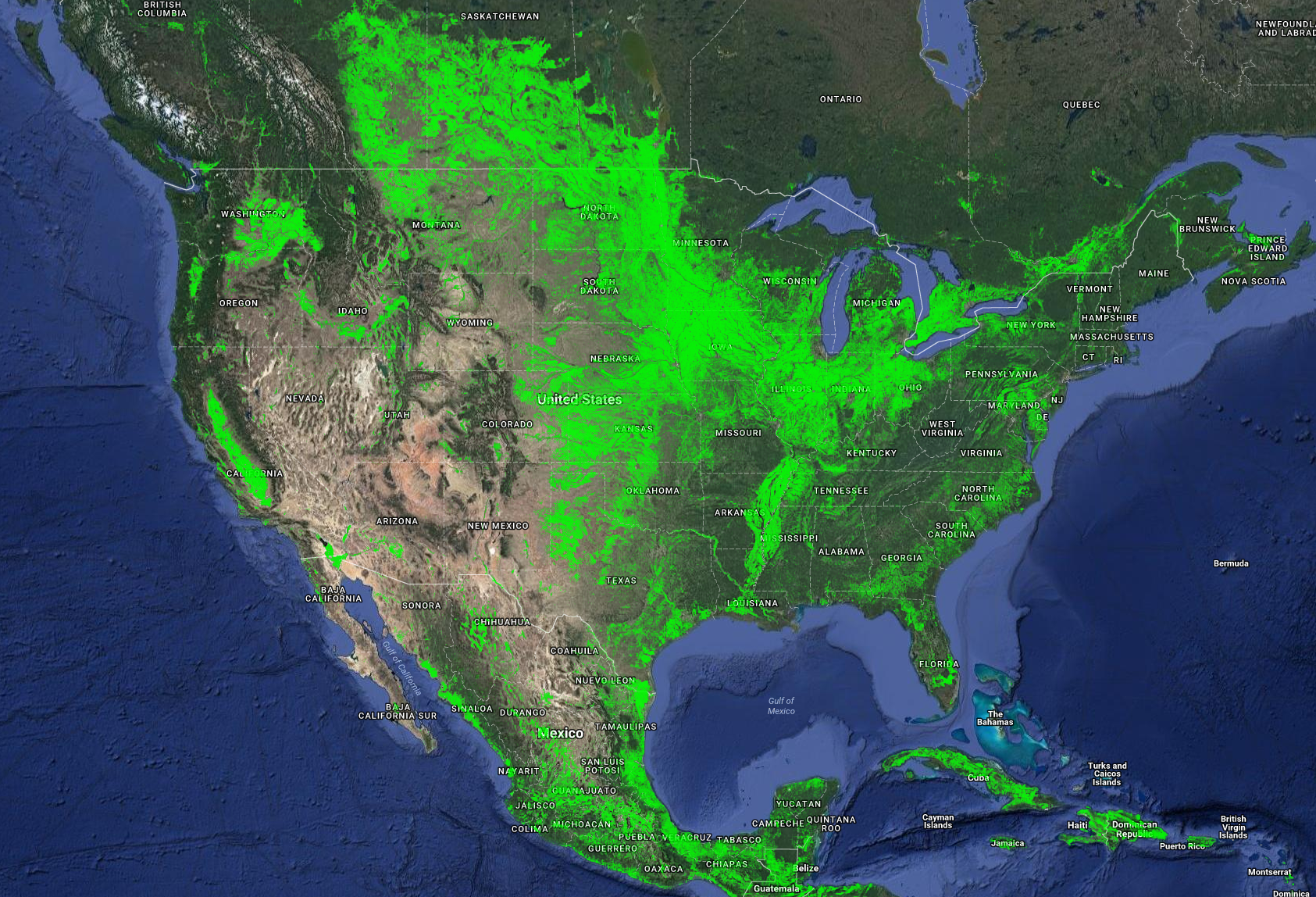

As a result of more than a century of disparate treatment by policymakers, individual and family owners of American farmland these days are not a particularly diverse group. White people own 98% of farmland in the United States and operate 94% of farms on that land. 63% are male, and 62% are over the age of 55. In Iowa, the numbers are even more extreme: 99.7% of farmers are white, 70% are male, and their average age is close to 60.

A map of American cropland, courtesy of USGS. Available at usgs.gov.

Nearly half of the landmass of the United States, or about 911 million acres, is devoted to agricultural production, and the USDA identifies almost 98% of farms on those acres as “family farms.” Average farm size varies wildly by state, from 55 acres in diminutive Rhode Island to sprawling 2500 acre ranches in Wyoming. In Iowa, the average farm size is 360 acres, or roughly half a “section,” one square mile of land.

Nearly half of the landmass of the United States, or about 911 million acres, is devoted to agricultural production, and the USDA identifies almost 98% of farms on those acres as “family farms.

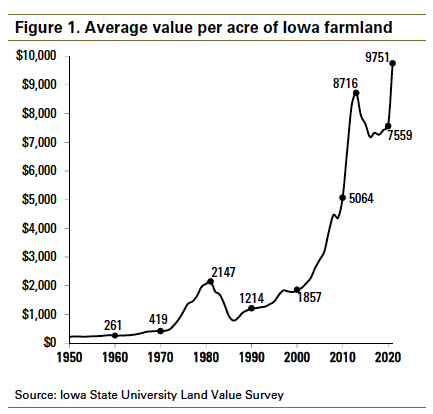

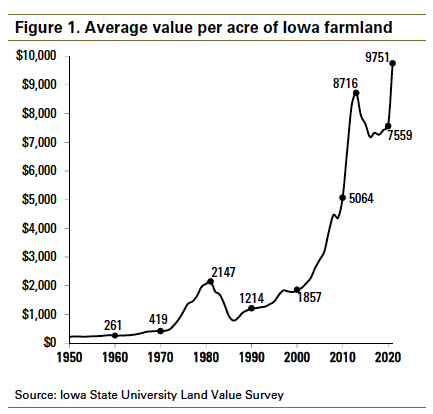

Agricultural land value falls along a similarly broad spectrum, with western states’ grazing range prices per acre falling far below the national average, and large tracts of agricultural land near northeastern cities carrying a premium associated with their development potential. Iowa has some of the richest agricultural soil in the world, and correspondingly high land values; at the end of 2021, the average price per acre was closing in on $10,000, about three times the national average.

Chart of farmland prices courtesy of Iowa State University. Available at extension.iastate.edu.

Leaving aside, for now, the addition of deep-pocketed financial investors into the farmland market, what may be counterintuitive to most is that the farmers who are engaging in “industrial agriculture” and the archetypal “family farmers” that are evoked in Congressional committee hearings and on the campaign trail are largely the same people. “The vast majority of farm families are incredibly wealthy, even aside from fixed farm assets like land, barns, and tractors. Maybe not in the top 1-5%, but they’re very wealthy, especially compared to the surrounding communities,” Rosenberg told me. “Both the data and anecdata are pretty overwhelming — farming in this country is almost entirely conducted by wealthy business owners.” Secchi agrees, and reminds me that most of the farms in this country are owned by these wealthy farmers. “Farmers are flush with cash and don’t know where to spend it, so they’re just piling dollars and dollars into these land assets.”

When I explained my evolving fascination with land access for small farmers intent on farming the “right way,” Rosenberg counters, “There are a couple of problems to that approach — one is that the assumptions it makes about farmland and farmers are incorrect — it posits a rural America that doesn’t exist. The data say that there are a lot of ‘small farmers,’ but most of those small farmers are wealthy landowners who produce food as a hobby.”

The data say that there are a lot of ‘small farmers,’ but most of those small farmers are wealthy landowners who produce food as a hobby.

Rosenberg asked me, “Do you know what the minimum amount of money a farm needs to make to be classified as a farm by the USDA?” I tried to remember some section of the Census of Agriculture I had looked at for a project the previous summer – a thousand dollars?

“Nothing. Zero dollars. When the USDA took over the Census of Agriculture in 1996, they created a category of farms called ‘point farms.’ The language is that these farms produce $1000 in agricultural goods annually, ‘or normally would.’ Some farms sell literally nothing, and almost 25% of farms in the Census of Ag are zero-sale. So, maybe you have a half-acre vegetable garden and some berry bushes for your family – theoretically, you could sell those veggies for more than $1000 a year. The USDA would include that as a farm that produces ‘specialty crops’ with zero or negative net income.”

Rosenberg speculates that this may, in part, be a way to help preserve the USDA’s funding and institutional power. “USDA has been subsidizing and encouraging the conditions under which the number of farmers has fallen drastically over the years — and with it, the USDA’s stakeholders. When the USDA goes before Congress and appeals for funding, one of the ways it makes its case is to tell them how many farmers exist and why they should help them. Everyone likes the narrative — the right wing likes how it helps maintain subsidies; Democrats get it both ways – they seek the Farm Bureau imprimatur and work with the more liberal groups, who support small-scale, often alternative farmers.” By evoking the idealized family farmer, everybody wins.

In addition to the agribusiness-friendly federal regulatory environment, Iowa has passed several state laws that ensure the status quo goes unchallenged, agricultural businesses continue to boom, and land values continue to trend upward. Iowa has become the Delaware of agribusiness, with a state government that has deep ties to – and accepts big money from – the state’s agribusiness interests, largely wealthy privately held family businesses like Iowa Select Farms. The Iowa state legislature has passed four so-called “ag-gag” laws since 2012 (all of which have been at least partially struck down by federal courts) which limit the protections granted to whistleblowers in the agriculture industry, most commonly workers documenting animal abuse in CAFOs.

“There are now more than 13,000 known confinement operations in Iowa, an estimated 400% increase from the beginning of the 21st century”

Iowa has had a “right-to-farm” law on the books since 1982, updated in 2017, which restricts the ability of Iowa residents to file “nuisance” suits against farm operations – a key legal accountability mechanism, given the agriculture loopholes in environmental regulations, for agriculture-adjacent communities suffering from eye-watering manure odor, high rates of respiratory disease, and contaminated drinking water due to agricultural pollution. Additionally, in 1995, the state legislature passed H.F. 519, which stripped county development boards of the ability to deny construction permits for new CAFOs, leaving those decisions to state officials who are less directly accountable to their constituents.

Following the passage of H.F. 519, the CAFO industry boomed – there are now more than 13,000 known confinement operations in Iowa, an estimated 400% increase from the beginning of the 21st century. The most significant CAFO construction boom happened between 2002 and 2006, under the oversight of then-Governor Tom Vilsack, a Democrat, who would go on to serve as the Secretary of Agriculture in both the Obama and Biden administrations.

A 1908 artist’s rendering of Iowa’s corn culture: “Our County Fair contest on Iowa corn” by W. H. Martin, born 1865-died 1940, marked with CC0 1.0.

In Iowa, corn, soy, and hogs exist in a particularly close relationship to each other, all on some of the richest agricultural soils in the world. Federal commodity supports for hogs and corn have been supplemented by the additional market and higher prices for corn driven by the federal government’s Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS) which requires, among other programs, that most gasoline sold be a minimum 10% ethanol. Chris Jones explained to me that in a traditional system, with hogs out on fields or more dispersed feedlots, the manure generated would be solid and easier to transport, or integrated into a closed-loop fertility system on the farm. With the rise of confinement agriculture, hogs are now raised by the thousands in enclosed sheds, and their manure and urine are mixed into a liquid form that is difficult to transport farther than a few miles, but needs to be trucked out to surrounding fields.

Per Chris Jones’s research, Iowa contributes 29% of the nitrate runoff, and only 4.5% of the water, to the Gulf of Mexico’s 6,000 square mile hypoxic “dead zone” at the mouth of the Mississippi-Atchafalaya River Basin. Image from Christopher S. Jones et. al., Iowa stream nitrate and the Gulf of Mexico, Plos One (April 12, 2018).

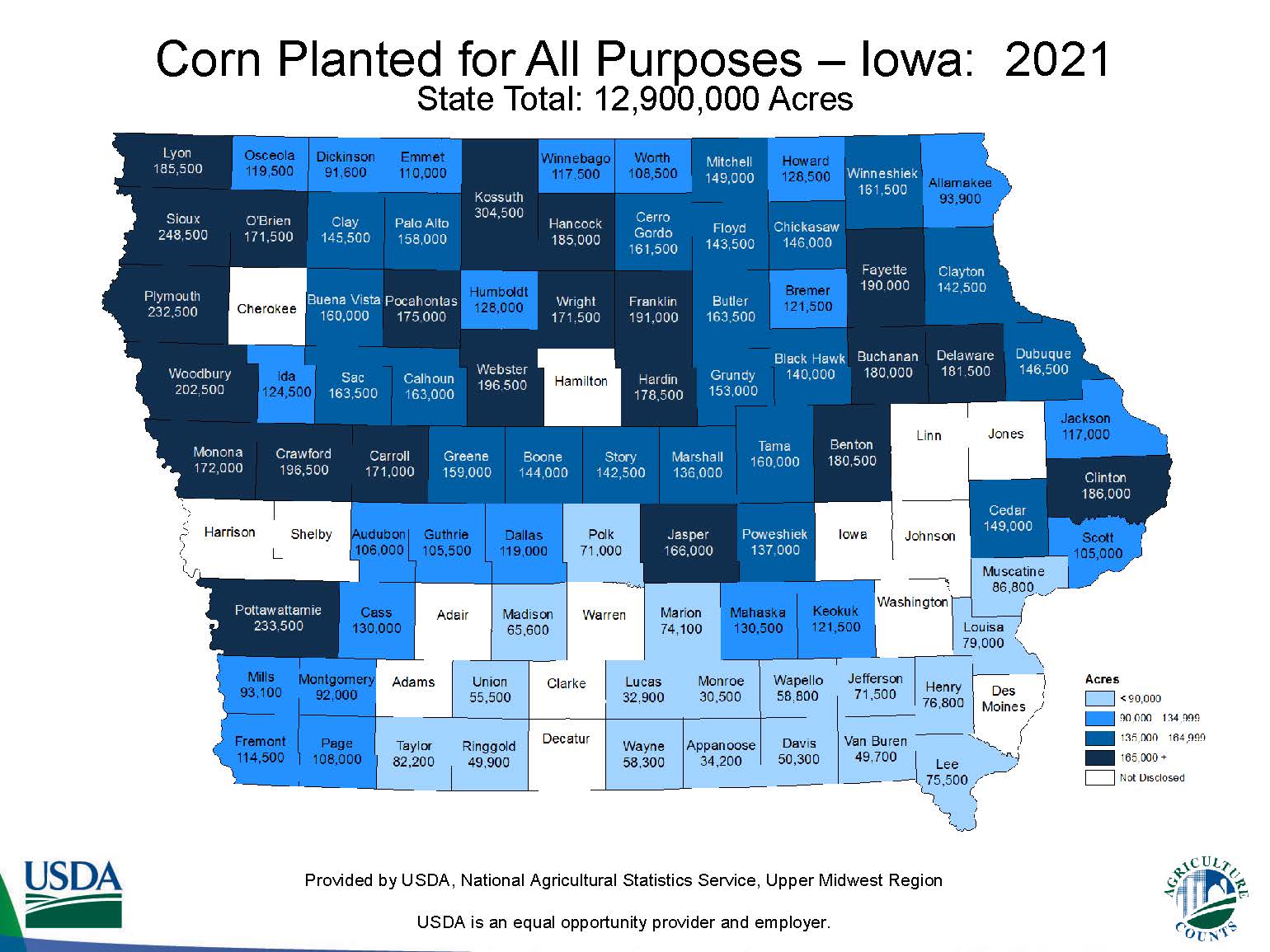

Each CAFO, under the terms of its permit, is required to follow a “Nutrient Management Plan,” detailing how they will dispense with the copious amounts of manure that hogs generate — in Iowa, the state’s 23 million (or so) hogs generate about the same amount of waste as 84 million people. As Jones explained, “Livestock operations need [corn]fields for manure distribution. Corn is the crop of choice because it can eat up more nitrogen than soy. There are areas in Iowa where close to 100% of the crop plantings are based on how much manure is being generated in that county.” He goes on, “Now hog production and [manure] fertilizer is decoupled from agricultural production — you have to move it from point A to point B to use it. You should almost consider the liquid manure more like artificial fertilizer.”

In Iowa, the state’s 23 million (or so) hogs generate about the same amount of waste as 84 million people.

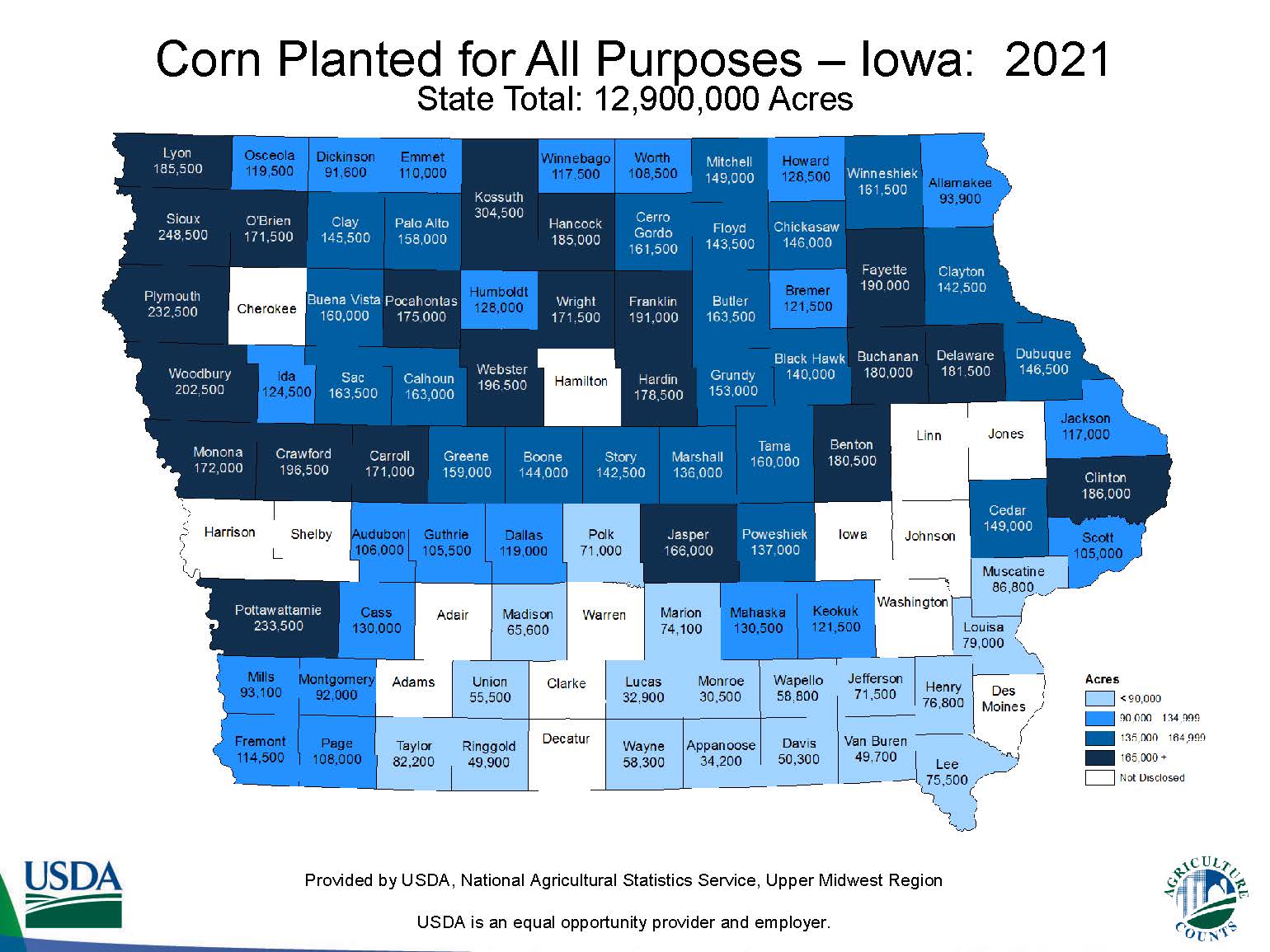

This new production system of hogs and corn and ethanol has transformed the face of Iowa agriculture. As Jones told me, “There’s always been a lot of corn here, but then soybeans opened the door to confinement agriculture, especially hogs. Before soybeans, we had a more diverse suite of crops — oats, barley, alfalfa — all displaced by soy. And now, even soy is starting to be displaced by corn.”

Map of corn plantings in Iowa provided by the National Agriculture Statistics Service. More at nass.usda.gov.

These days, nearly all of the cropland in Iowa is devoted to corn or soy. Although some fruits and vegetables are still grown in the state, the acreage devoted to them is no longer significant enough to rate on state agricultural reporting. As Jones pointed out in a recent blog post, it’s mind-boggling to think about what else could grow on the 7 million acres of agricultural land in Iowa currently used to produce corn for ethanol alone. “What else could we do with that 11,000 square miles… you might ask? Let me think for a minute…: 1.1 million acres: grow enough dried beans for every person in the United States; 360,000 acres: grow enough potatoes for every person in the United States; 220,000 acres: grow enough apples for every person in the United States; 150,000 acres: grow enough canned sweet corn for every person in the United States . . . .” Jones continues to name additional food crops that Iowa could supply within ethanol’s footprint and asks, “Iowa has the good fortune to be the best place on earth to growth stuff, including annual crops… Why are we wasting this place on ethanol?

It’s mind-boggling to think about what else could grow on the 7 million acres of agricultural land in Iowa currently used to produce corn for ethanol alone.

Although the number of farmers in the U.S. continues to decline, the size of farms, farm businesses, and farm incomes climbs steadily upward. In Iowa, the number of hog farms has decreased by more than 80% over the last 30 years, while the hog population has increased by about 50% . One “family farm,” Iowa Select Farms, raises 15% of Iowa’s pork production – around a billion pounds of pork per year – in confinement sheds scattered throughout half of Iowa’s counties. In 2022, 24,000 fewer farms grew 1 billion more bushels of corn on half a million more acres than they did in 1992. “Get big or get out,” indeed.

One “family farm,” Iowa Select Farms, raises 15% of Iowa’s pork production – around a billion pounds of pork per year – in confinement sheds scattered throughout half of Iowa’s counties.

![[F]law School Episode 13: The Migrant Trap](https://theflaw.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Drury_FB2-e1742192209662-640x427.png)