The Pink Tax is not an actual tax. Instead, the World Economic Forum explains that Pink Tax describes the phenomenon where:

Men and women [] buy similar day-to-day products. But research shows that consumer products targeted and advertised to women are sometimes more expensive than comparable products marketed to men. This disparity is referred to as a so-called pink tax.

The Balance Money explains that “[i]f a company believes a consumer will still buy a product even though it’s more expensive than others just like it, it may choose to do so.” Companies, however, do not simply have an option to do so—they do.

The reason: men’s razors are sharper. Too sharp for women’s legs but just right for men’s faces. . . . “Venus is owned by Gillette, which makes the men’s razors that so many of us are using.”

The mascot of the Pink Tax is the pink razor. Michelle Chang, a student at the Drexel University College of Medicine, studied the cost of disposable razors from Amazon, Walmart, and Target, and found that women’s four-bladed razors were priced sixty-six percent higher than four-bladed razors marketed to men and women’s five-bladed razors were priced forty-seven percent higher.

The price difference may make perfect sense—maybe razors made for women are really better than those made for men. But in the 2010s, women started doubting this presumption and encouraged others to buy men’s razors. This was so pervasive that Venus reported that about a third of women were using men’s razors. Why? The company reported that women found that men’s razors were “sleek, shiny, and silver”—not about price. In response, Cosmopolitan, using Venus’s data, cautioned women against using men’s razors. The reason: men’s razors are sharper. Too sharp for women’s legs but just right for men’s faces. One might wonder if Venus is simply looking out for their bottom line. Not so—Cosmopolitan dispels any concerns about bias, saying to the skeptics, “know that Venus is owned by Gillette, which makes the men’s razors that so many of us are using.”

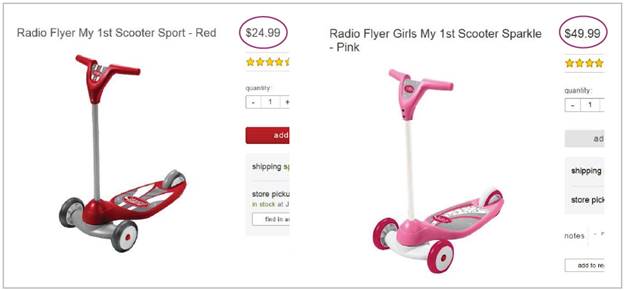

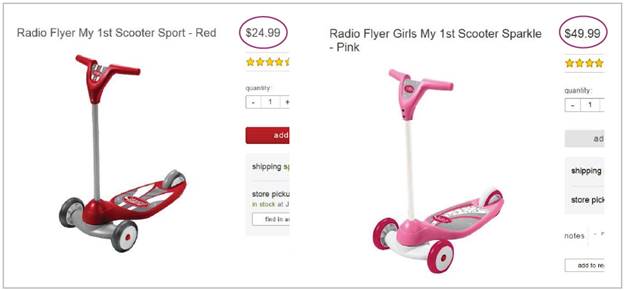

The Pink Tax bleeds beyond the beauty industry and throughout the market. In 2015, Target listed these two scooters, exactly the same in all respects besides their color and design. “My 1st Scooter,” presumably marketed towards boys, was half the price of the “Girls My 1st Scooter Sparkle.” Even the helmets to protect girls as they ride on their more expensive scooters cost nearly twice the amount as helmets marketed towards boys.

Scooters listed on Target

In 2015, the New York City Department of Consumer Affairs produced a report comparing the prices for various personal-care products and found a clear premium on products marketed to women: 48 percent more for shampoo and conditioners, 11 percent more for razors, and 15 percent more for shirts. The California Senate Committee on Judiciary and Senate Select Committee on Women, Work & Families found that women in California pay an average of $2,381 more than men per year for the same goods and services.

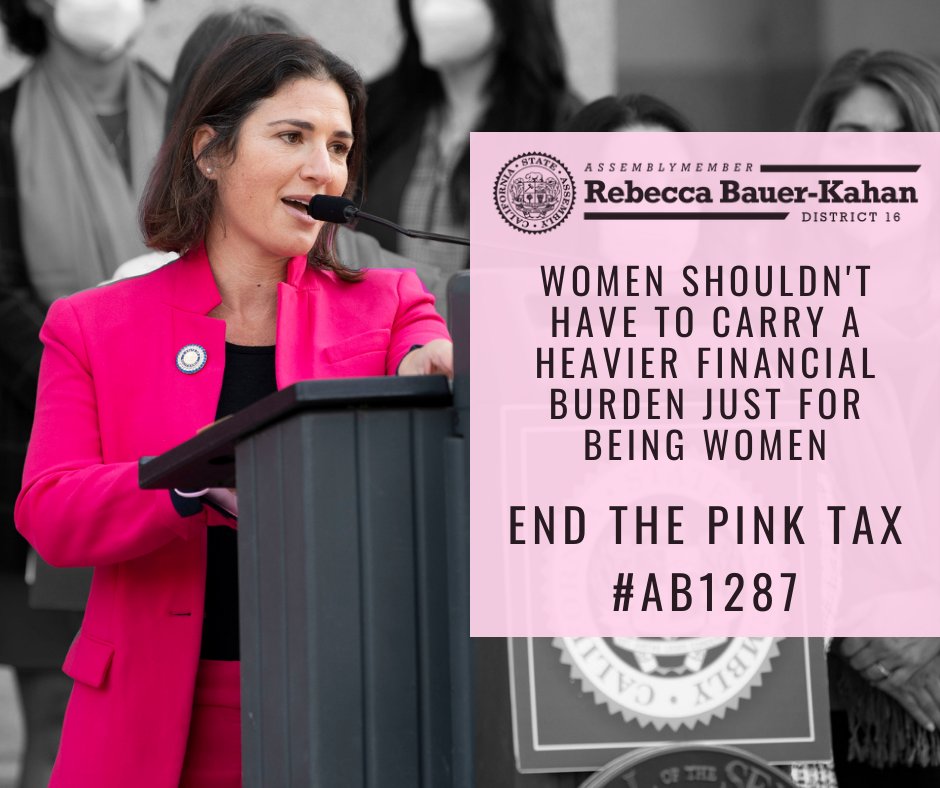

State governments are axing the pink tax by assessing penalties against businesses that charge a differentiated price for essentially the same product. For example, California’s businesses face a $10,000 penalty for charging more for the “women’s” version of essentially the same product, and $1,000 for each subsequent violation. Specifically, when the products do not have substantial differences in materials used in production, are intended for similar use, have similar functional design and features, and have the same brand or parent company, businesses are not allowed to charge different prices. However, there is still room for pricing products differently based on the following factors:

-

- The amount of time it took to manufacture the goods.

- The difficulty in manufacturing those goods.

- The cost incurred in manufacturing those goods.

- The labor used in manufacturing those goods.

- The materials used in manufacturing those goods.

- Any other gender-neutral reason for charging a different price for those goods.

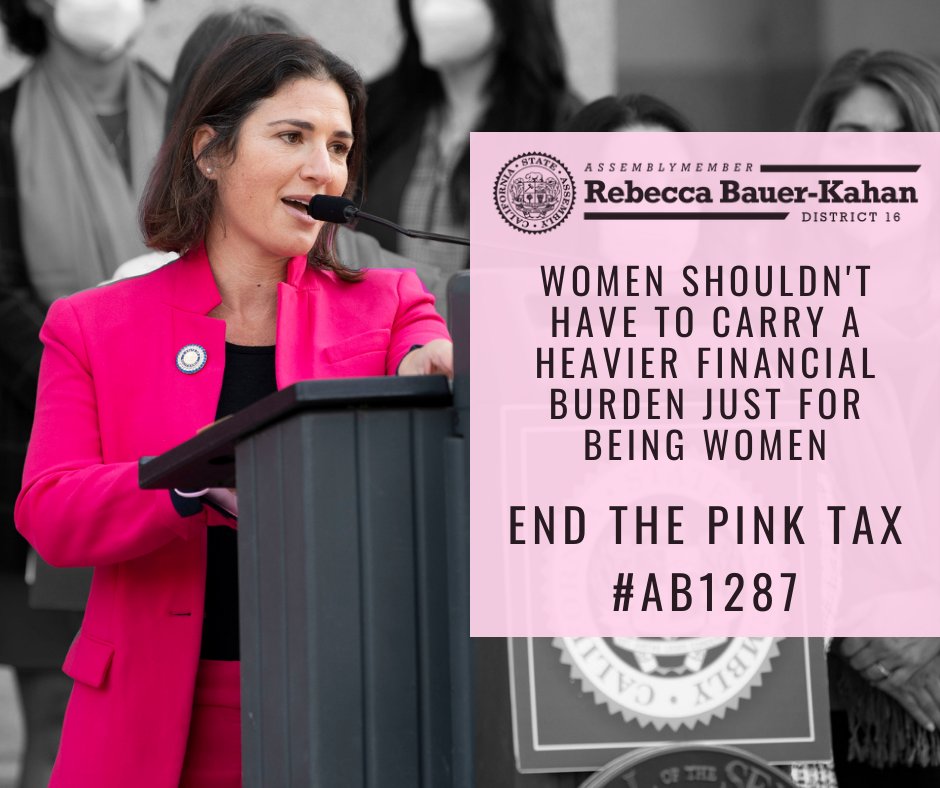

Assemblymember Rebecca Bauer-Kahan, the sponsor of California’s Pink Tax Bill

This is nearly identical to New York’s rule but has higher penalties. Even with a $10,000 initial penalty, many experts are skeptical of the effectiveness of these bans. Sociologist Liz Grauerholz says:

It is almost impossible to make a side-by-side comparison. And I honestly believe that manufacturers have gotten pretty wise to the pink tax, so they make them [men’s and women’s items] look like completely different products to make those side-by-side comparisons really difficult.

A legislative aide who worked on California’s bill explains that:

[G]endering of products is really subjective…. And you can get out of the enforcement of this bill if you just prove that you manufactured something differently. The color of something doesn’t count as manufacturing differently, but a lot of other things can. So really the only thing you’ll see this in is like the most egregious violations where it’s literally the same product, but it’s pink.

In the face of these state bans, a study published in March warns politicians like Representative Jackie Speier, who has introduced the Pink Tax Repeal Act in Congress four times, against aggressively pursuing the issue: “our findings call into question the role of government intervention to reduce the pink tax.” The authors did not cite the limited scope of these bans, but instead echoed Venus and Cosmopolitan’s claims that pink tax does not exist: “In an apples-to-apples comparison of women’s and men’s products with similar ingredients,… we do not find evidence of a systematic price premium for women’s goods.” The authors explain that, although the pink tax is a seductive issue:

[I]f there is a social norm that pressures consumers to purchase and/or use products that align with their gender presentation, a firm could segment consumers simply by adding gender labels or color cues to their products. Alternatively, if consumers are uninformed or misinformed about product ingredients, they could mistake the differences between men’s and women’s products.

But this could not be possible. Dispelling the myth of the pink tax, the authors point out that “information about ingredients is readily available on product packaging” and pricing for personal care products are posted “where a woman can typically observe shelf prices of products aimed at men.” What stops a woman from switching her Secret Real Lavender for Axe when the prices and ingredients are right in front of them? After all, “there is no rule barring her from buying a men’s product.”

Instead, the authors explain that we are confusing “second degree price discrimination” for actual discrimination, where “the consumer type with a higher taste for quality buys a more expensive, higher-quality product and enjoys higher consumer surplus.” Although these differences may seem “unfair if they are sustained through frivolous or spurious attributes,” the authors clarify that “firms may set markups in personal care to reflect differences in product performance that bring real value to customers.”

What stops a woman from switching her Secret Real Lavender for Axe when the prices and ingredients are right in front of them? After all, “there is no rule barring her from buying a men’s product.”

In the article’s feature by the Cato Institute, the authors once again caution against overeagerness on the part of legislators and policymakers where “[u]nfortunately, there is a dearth of evidence on the pink tax to guide legislative action.”

The authors are correct in that there has been a marked increase in the number of women who check ingredient labels before purchasing beauty products. Driven by concerns from the growing number of reports of toxins in beauty and personal care products, 59 percent of women now check their product labels. But they “often do not recognize ingredients on the labels.” 81 percent of women surveyed by Label Insight did not recognize ingredients on labels of personal care products. In contrast, only 2 percent of women reported that they always understand the ingredients on product labels.

For one of the authors, educating overeager policymakers seems to be part of her repertoire. Anna Tuchman is an associate professor of marketing at the Northwestern Kellogg School of Management, where her work has also warned of the ineffectiveness of the soda taxes and bans on e-cigarette advertising. In fact, she cautions that such bans on e-cigarette advertising actually increase the use of e-cigarettes. Numerous studies have found the exact opposite impact and the American Medical Association supports a ban on e-cigarette advertising.

“If my finances suddenly changed, I’d stop buying new clothes before I’d stop buying skincare.” Dee, a woman who spends $6,000 a year on skincare, shares that “[f]eeling good, regardless of how I look, means more to me than keeping out of my overdraft.”

Women are not only hypothetically willing to sacrifice financial security for the sake of beauty—they do.

“If my finances suddenly changed, I’d stop buying new clothes before I’d stop buying skincare.” Dee, a woman who spends $6,000 a year on skincare, shares that “[f]eeling good, regardless of how I look, means more to me than keeping out of my overdraft.”

For Ayesha, this is her reality: “At the moment, I’m on maternity leave, which means that I don’t have much income. Since having a baby I feel like my confidence has taken a hit and I want to look fresh and awake… I just can’t seem to get enough. I always want more and more. I do feel down when I use credit to buy these things, but I get influenced a lot by Tik Tok beauty trends and I feel like I need everything I see.”

Dee and Ayesha are not alone. Groupon, the company with the tagline “Save Up to $100 a Week on What You Do Every Day,” reported that women routinely spend an average of $3,756 a year on their appearance. Without accounting for inflation, this amounts to $232,872 over a lifetime. In contrast, men report that they spend an average of $2,928 per year, about one-fourth less than women. As the online beauty and style publication Byrdie puts it, “[t]he Average Cost of Beauty Maintenance Could Put You Through Harvard.”

The Pink Tax bill has been introduced in the California legislature every year for over two decades. What has killed this bill in one of the most progressive states in the U.S.? The private right of action. Every legislative cycle, the California Retailers Association and the California Chamber of Commerce effectively guaranteed the failure of any pink tax bill that contained a private right of action.

“It’s not the small businesses saying it. It’s Cal Chamber saying: our small businesses will die.”

Private right of action or not, a ban on the Pink Tax would likely have no impact on small businesses. To recover penalties or damages sufficient to justify civil enforcement or litigation, there would need to be a high number of infringements that only the largest retailers can provide.

In a 2017 press release, the California Chamber of Commerce explains that “CalChamber has identified AB 1576 as a job killer because the legislation will create the same type of litigation environment that has plagued the business community with respect to disability access.” To be clear, the right to sue a retailer for charging women more is seen as a “job killer.”