Big Law’s Capture of Students of Color

How and Why Harvard Law students of color are being funneled into Big Law

Rosie Kaur

November 13, 2022

Azucena Marquez went to Harvard Law School wanting to be an immigration attorney. Her family immigrated to the United States from Mexico, and faced significant adversity, from difficulties crossing the border to struggling to find decent work once in America. “I wanted to be in a position where I could help people who have struggled through the immigration system as my family has,” she says. But her immediate career ambitions quickly changed as soon as she stepped onto Harvard Law School’s campus. “I feel like that is a very common experience. A lot of us lose why we came to law school in the first place as soon as stepping into [these] doors.”

Students enter Harvard Law School (HLS) with big, idealistic dreams. Their personal statements are full of rhetoric about changing the world through the tools of law. However, those same students leave law school deciding to work at large, multinational corporate law firms (otherwise known as “big law”), firms that work against the very efforts that inspired students to go to law school, to begin with. Big law firms have historically had a deep capture over Harvard Law School’s culture and curriculum. HLS encourages and prepares students for a career in big law over a public interest one.

While Harvard Law students generally face a strong current to work in big law, students of color from marginalized backgrounds like Azucena face this current at an even greater intensity. This is an outcome that is speculated amongst Harvard Law students and faculty, yet an understanding of the deeper, systemic casual mechanisms are seldom explored. As a student of color attending Harvard Law who personally has experienced the deep capture of law firms, I feel particularly equipped to explore this topic.

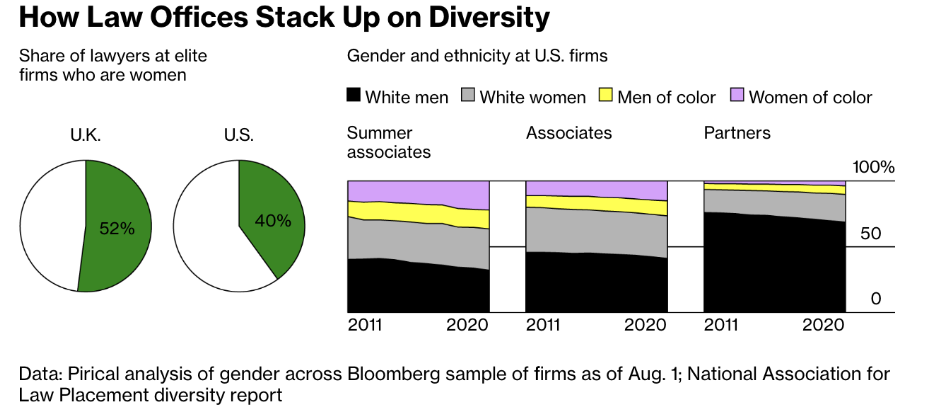

HLS is ranked among the 10 most racially and ethnically diverse law schools in this country, which further emphasizes the need to explore the vocational patterns of its students. Although there is, unsurprisingly, a lack of institutional data from Harvard Law on the percentage of students of color going into big law and the reasons for this phenomenon, a study conducted by Harvard Law School Professor David Wilkins on the vocational decisions of black HLS students shows that 72% of black Harvard Law graduates start their career in the private practice, primarily at large law firms. This is a greater percentage than that of all HLS alumni. According to a Harvard Law School Career Study (HLSCS), 61% of the general student population goes into private practice as their first job out of law school.

Additionally, only 40% of black Harvard Law students reported that they intended to start a career in big law before entering law school, a number that jumped by over 30% upon graduation. This number signifies that the law school journey has a significant influence on the career decisions of students of color.

Law firms have put in a considerable amount of work to target marginalized students, increasing the likelihood that students of color will go into big law. Students of color at elite institutions like Harvard Law are introduced to big law the summer before law school, through a firm internship designed to prepare underrepresented students for law school. They are offered financial incentives for working in big law their first-year summer through a Diversity Fellowship, while their peers spend the same summer exploring their public interest passions. Finally, race-based affinity group funding comes primarily from law firms, obligating students to prioritize law firm events over other professional activities such as public interest events.

Harvard Law also relies a great deal on law firms’ corporate power and funding, thus influencing the way its legal education is taught. Professors tell their students, time and again, that their personal experiences with race and the law is not primary to their core legal education, thus numbing student passions.

Law firms’ efforts to recruit more students of color stem from the rise in the importance of diversity in the corporate space: diversity is now part of the profit-maximizing scheme that corporate investors value. This corporate hunt to maximize profit seeps into the experiences of students of color on their law school professional journey.

When law firms open their doors to increase their diversity, they often, though certainly not always, are working with students who are especially vulnerable, due to their experience with race and its ties to socioeconomic status. Azucena, for example, had to decide between working in the career she was passionate about, and taking a big law job that would help her support her family. Her decision to go into big law ultimately stemmed from pressure to pay off her loans quickly to help her family, and build the inter-generational wealth she entered law school lacking.

Law firms’ efforts to recruit more students of color stem from the rise in the importance of diversity in the corporate space: diversity is now part of the profit-maximizing scheme that corporate investors value.

When asked why she felt pressure to work in big law, Azucena said: “For one, the huge amount of debt that I saw…I was like, oh my gosh if I become an immigration attorney, there is absolutely no way I will be able to pay this off and I will not be in a position where I will be able to help my family.”

Rather than working to really solve the systemic issues at play, law schools and law firms have created a band-aid solution: help students of color create wealth for themselves through a career in big law. Yet, this solution moves students of color, those who are in the best position to understand and fight for justice, to use their skills to perpetuate the systemic issues that brought them to a place of disadvantage to begin with.

Law firms have historically contributed to causing and perpetuating gentrification, increasing the wealth gap, taking resources away from the poor, creating environmental damage primarily in communities of color, and so much more. The band-aid diversity solution causes internal friction, dissonance, and discomfort amongst students of color. It furthers the injustice they face, depriving them of opportunities to really make the change they wish to see.

Students begin to see themselves as bad players in the good versus bad student dichotomy, rather than as people living in a world of capitalistic, systemic injustice.

“I feel like a bad person oftentimes, especially because I know a lot of the law firm job that we are doing is going to be hurting the communities that I come from,” says Azucena.

If viewed solely from an individualistic level, diversity initiatives appear to be a strong solution to confronting the issue of the lack of access people of color face in elite spaces like big law firms. Students who are playing in the field as it is set are able to get more access to resources to build their wealth in a workplace that has historically been white. However, the individual perspective gives the illusion of meaningful progress. When we zoom out and see groups of students of color all being funneled into an institution that harms their communities at a higher level of intensity than their peers, we see that inequity is not being resolved through diversity.

![[F]law School Episode 8: Selling Harvard Law Students](https://theflaw.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/Screenshot-2024-09-08-at-9.59.54 AM-640x427.png)