Broken American Dreams

On Uber’s destruction of the taxi industry

Rosie Kaur

July 31, 2023

“What breaks me most is imagining my father leave the house at the crack of dawn to take the day on. Bag of water and fruit in hand, he probably just paused in disbelief that the moment was there. After 25 years of blood, sweat and tears, he was back to where he started.” Mandeep Singh.

Mandeep’s dad was a New York taxi driver. After working tirelessly for 25 years, he saved enough money to purchase a taxi medallion. Because of the infiltration of app-based ride share driving services such as Uber and Lyft that drove the taxi industry out of business, Mandeep’s dad, along with thousands of other immigrant and taxi drivers of color, had to file for bankruptcy.

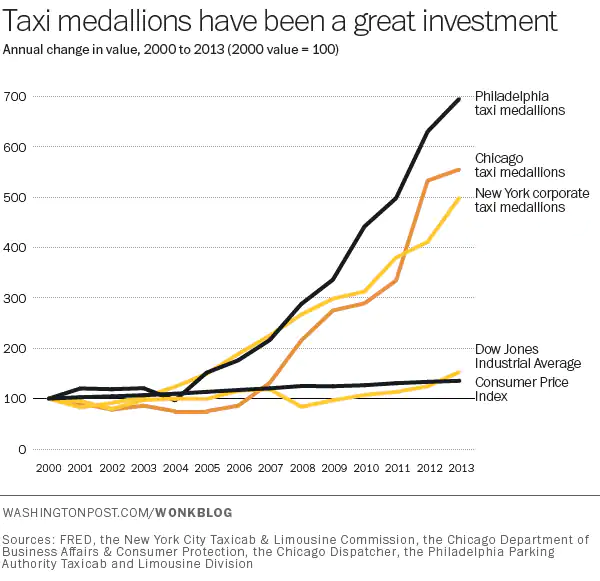

From the 1940s to 2014, taxi medallions were considered to be a successful investment for taxi drivers. Approximately 90% of taxi drivers in New York are immigrants. Many immigrant taxi drivers who had been driving taxi since moving to the United States saw owning a taxi medallion as their way into the middle class. In fact, beginning in 2004, the Bloomberg administration begun placing ads to purchase taxi medallions in immigrant newspapers. They promised drivers it was a way to buy into the American dream. And before Uber came to being, it was.

Chart by the Washington Post

At their height in 2014, yellow taxi medallions were selling for $1 million in New York City. Since the proliferation of Uber, Lyft, and other rideshare apps beginning in 2011, the medallion value decreased significantly. By 2018, a New York taxi medallion was only worth $170,000. Suddenly, the American Dream that taxi drivers believed they finally had access to was slipping from their fingertips.

“Being the optimist he is, [my father] valued the role that drivers played. On top of a world class public transportation system, taxis were an iconic part of both the aesthetic and the underbelly of the economy. It all changed in 2015. Uber and Lyft, and other ride share companies proliferated the market. The reason why medallion prices were so high is because there was a limited supply but high demand. That model broke when ride sharing apps came to be.”

“My father had to file for bankruptcy because he was not making the money to pay off the medallion. The bank whose loan I defaulted on came to our taxi, parked outside our house and took off the medallion…rendering the car useless and putting my father out of an immediate job. I called [my dad] after to see how he was doing. He was cleaning the taxi that properly looks naked now. Picking up loose change left in between seats, the broken shards of a three-decade long American Dream. He said he knew it was coming, but it’s hard. It was $100K and a lot of time not spent with my family so that he could chase his dream.”

This situation was not limited to Mandeep’s family. Unfortunately, his family did not face the worst of the brunt of the crash of the taxi industry. Thousands of taxi drivers across the United States, with New York at the epicenter, were losing their jobs and filing for bankruptcy on their taxi medallions. Taxi drivers also faced foreclosures and evictions.

Additionally, at least nine taxi drivers in New York City alone are believed to have died by suicide because of the downfall of the taxi industry. In May 2014, taxi driver Yu Mein Chow was found dead in New York’s East River. He had taken out a loan in 2011 to buy a $700,000 taxi medallion. After the disruption of Uber, he felt hopeless about his ability to pay the taxi medallion loan, his wife’s medical bills, and his daughter’s college education. His death followed the heartbreaking suicide of many other taxi drivers, including driver Doug Schifter, who died by suicide in front of New York City Hall.

Picking up loose change left in between seats, the broken shards of a three-decade long American Dream.

While many blamed the New York government for their lack of ability to support taxi drivers, the taxicab industry was operating on a unlevel playing field. The taxicab industry had limited capital investment in vehicles and employees, and was limited by city regulations. For example, New York City had limited the number of yellow cabs available to about 13,500. Uber, however, had no such limits. Rather, the number of rideshare vehicles on the streets tripled between 2010 and 2019, from 40,000 vehicles to over 120,000 vehicles.

Uber ultimately was able to destroy the taxi industry by using a ridiculous amount of investor money, skirting local regulations through political connections, and bribing academics to purport a narrative that Uber was helping consumers and drivers alike.

Uber’s rise to power

Uber was founded in 2009 in San Francisco by Travis Kalanick and Garrett Camp. They were attending an annual tech conference The Economist describes as “where revolutionaries gather to plot the future.” Both men had previously sold startups that they co-founded for large sums. Kalanick sold Red Swoosh to Akamai Technologies for $19 million, and Camp sold StumbleUpon to eBay for $75 million.

Uber was founded on the idea of “disrupting” the ride sharing industry. In the tech world, “disruption” is viewed as something that will positively benefit society by changing the status quo. It is a response to a failure on the part of industry leaders to innovate fast enough to survive. Uber espoused the narrative that the taxi industry was doing something wrong because of its high prices, and that Uber was doing something right by offering unrealistically low prices and evading local regulations to promulgate its services. Uber hired policymakers and academics as part of its public relations strategy to use one-sided rhetoric to convince authorities, tech elites, and the public that Uber was a positive disruption to the taxi industry.

According to Hubert Horan, an expert on the economics of transport competition, Uber was the first company to promote corporate narratives through press and the academia from its very onset. “There are lots of companies that have [public relation] armies after they’re big and established. But [Uber] was the very first company where this was a strategic priority from day one. They were the first to use…techniques to bamboozle politicians and investors from the get-go.”

Uber started its public relations strategy guns blazing, hiring Head of Public Relations, David Plouffe, Barack Obama’s former campaign manager, and Jim Messina, Plouffe’s deputy, to convince politicians to legitimize Uber, despite it openly flouting regulations and laws, such as labor laws, local drop-off and pick-up regulations, the American Disabilities Act, and many more. They sold the narrative that flouting such regulations would ultimately be more beneficial for drivers and consumers alike. Uber was above the law. A leaked memo from Uber titled “Leveraging the US government to support Uber’s international business,” showed that sitting and former US government officials were key to Uber’s expansion plans.

Uber also maintained a close relationship with academic economists and used their false research to spread narratives of Uber’s predicted success. In fact, Uber’s employees co-authored academic papers with brand name scholars that were used to back up the company’s public relations strategy. One of the writers, Alex Krueger, admitted to having had worked as an Uber consultant while he was also writing the initial draft of his paper on Uber. According to the Guardian, high profile professors in the United States and in Europe were paid six-figure sums for media research that Uber “created well-paid jobs, delivered cheap transport to consumers and boosted productivity”. The academic papers championed the idea that Uber’s drivers had higher earnings and greater job satisfaction than traditional taxi drivers, and that Uber’s growth was driven by a major productivity advantage.

One of the papers gave credibility to the claim that Uber had a huge productivity advantage (38 percent overall; 66 percent in some cities) over traditional taxis thanks to its cutting-edge technological innovations and its evasion of traditional regulations. The paper made it seem as if drivers were able to be more efficient (make more money in less time) when using Uber versus taxi. However, the authors missed key data points. “The paper significantly overstated its Uber vs taxi utilization advantage by using incompatible measures of total work hours—total shift hours for taxis, time with the app on for Uber. Taxi drivers have a huge incentive to drive very long shifts in order to cover daily vehicle lease and fuel costs, while Uber drivers have incentives to drive short shifts during demand peaks, and have incentives not to turn their app on unless prepared to immediately accept ride requests. The paper concealed this by not presenting any of the actual data (hours/miles with passengers, total hours/miles worked) used in the utilization comparison,” says Horan.

Uber also maintained a close relationship with academic economists and used their false research to spread narratives of Uber’s predicted success.

Additionally, this data did not consider the damage to the supply and demand of drivers and consumers, repercussions of which drivers faced on the ground. “So many Uber drivers and Lyft drivers joined [the ride service industry] that the supply and demand got massively misaligned…Because of the lack of regulation, there was less money to go around for drivers…there were a lot of drivers competing for the same rides, which made it challenging for both taxi drivers and Uber drivers,” says Mandeep.

Despite what Uber’s paid researchers and politicians say, Uber has not been a positive switch for all drivers. According to Mandeep, his family members made much less money when driving Uber versus when driving taxi. He said that on average, they used to make $300 to $500 a day driving taxi; with Uber, however, they made $150 to $250 on a really good day.

“People who have done both [taxi and Uber] would acknowledge that the hourly rate that you make is probably lower because Uber takes so much. I took an Uber to the airport. I got charged 20 dollars, and the Uber driver was getting 9 or 10 dollars…there is a very frustrating and clear cut that Uber is taking at the expense of drivers themselves. Uber drivers feel that and understand that,” says Mandeep.

Broken Promises

After pricing out the taxi industry, eight years later, Uber is still making negative profit, has increased its ride prices beyond what it initially advertised to the public, and is now even striking deals to list all New York City taxis on its ride-share app. Behind the prevailing narrative of Uber being a successful, innovative business, is a corporation in debt that has destroyed the lives of hard working, immigrant families around the world.

Despite its economic failures, people still view Uber as an incredibly successfully company. Uber manages to promote its corporate narrative through press and academia, explain away its losses, and conceal the unsustainable nature of its business model. But when are they going to make money? How can they make money?

Uber, like hundreds of other tech companies, has always been hopelessly uneconomic. It offers ride sharing prices that the market is not willing or able pay. It can do so because it has the investor money to back its operations, allowing Uber to price out the taxi industry while still making negative profit. Uber has lost $31 billion in their actual ongoing car service and delivery businesses as of the end of 2021, and has yet to produce even $1 of positive cash flow.

“[D]espite its $31 billion in losses and the fact that they’ve never generated even $1 of positive cash flow, conventional wisdom still says that this was a wonderfully innovative company that was smart and successful and greatly improved urban transit. It’s currently valued at something north of $40 billion—ostensibly, a viable business that people should invest in based on its future earning potential,” says Horan.

According to Horan, Uber manipulated its accounting to deceive the public about how much money they were actually making. They mixed untradeable equity from businesses that failed and are no longer part of their ongoing business with the results from the business they are operating. For example, Uber had to shut down its operations in China, Southeast Asian, and Russia because the business was failing there. They lost billions of dollars there, but “sold” their work “to the incumbent that had driven them out of business,” netting money they could show as profit. Uber ultimately included forms of equity that were not tradeable (and thus not relevant) in their financial reports, which made the company look like its services were more successful than they were. Uber used this tactic right before it went public.

Photo by charlesdeluvio on Unsplash

Uber not only disrupted the taxi industry, but it also completely changed the way we, as a society, think about the infrastructure of our travel. We have changed our habits based on the assumption that we can be driven around conveniently, and for cheap. One CNBC article tells the tale of a woman who has become addicted to Uber and is trying to stop. She spent almost $700 on Uber in one month because she got used to the convenience. What she may not have recognized, is that Uber has increased its prices since the onset of the app. Uber has created a human reliance on the convenience of its application based on the assumption that the rides are affordable, all while dramatically increasing its prices.

Uber has created a human reliance on the convenience of its application based on the assumption that the rides are affordable, all while dramatically increasing its prices.

While many were angry about what Uber did to taxi drivers, those who were pro-Uber and are pro-tech believed the disruption was necessary for the betterment of society – that betterment involved being able to travel for a cost much lower than what taxis charged. However, Uber has not been able to keep its promise of low prices. According to data from Rakuten, Uber prices rose 92% between 2018 and 2021. According to a separate analysis report, Uber prices rose 45% from 2019 to 2022.

Why is this happening? Uber has lost over $30 billion since becoming public, and has relied enormously on investor subsidies to continue fueling “America’s ride-hailing habit”. In short, Uber created a societal reliance that it could not afford. It used investor cash to corner the private transportation market, destroyed the taxi industry, and then stopped charging riders less than it was paying drivers to try to make some profit. These days, an Uber from Manhattan to JFK Airport costs around $100, which is very similar to the price of a taxi.

It is doubtful that Uber will be able to reach profitability without increasing its prices more than it already has. “Uber has always said it would reach profitability at scale, thanks to network effects, etc.,” journalist Alison Griswold writes, “but what is scale if not a company that operates in 72 countries and more than 10,500 cities, which last year had 118 million active users every month and completed 6.3 billion rides/trips/deliveries? Uber is the definition of scale, yet it is still nowhere near consistent and reliable profitability.”

Uber drove out existing taxi drivers and systems that were working efficiently, under the guise that it had a seamless business model that would be profitable and benefit society.

Striking Deals with New York City Taxis

Uber’s original narrative was that the taxi industry is awful — taxis are inconvenient, too expensive, and the drivers do not care about their customers. Ubers are convenient for both customers and drivers, and will allow drivers to make more money. “[Taxis] hate their passengers, they don’t like technology, you can’t get a cab on Saturday night or when it rains, and look at all these middle-class and poor neighborhoods that get awful service.”

Now, eight years later, Uber has altered its narrative from being anti-taxi to pro-taxi. Uber’s goal is to have “every taxi in the world on the Uber app.” Uber is striking deals to list all New York City taxis on its ride-share app, disregarding its former vow to disrupt the problematic taxi industry.

“After its business model has shown the failures to protect drivers from ridership downturns and rising gas prices, Uber is returning to its roots: yellow cabs,” Bhairavi Desai, the executive director of the New York City Taxi Workers Alliance.

In New York City, Uber is teaming with tech platforms Creative Mobile Technologies (CMT) and Curb to eventually have all New York City taxi cabs available on its app. Anyone with the Uber app will have access to thousands of yellow taxis that operate on the CMT or Curb platform. Taxi drivers will see Uber-originated fares on their driver monitors, which they already use to service e-hails from taxi apps.

Uber has, of course, made it appear as if its efforts to partner with the taxi industry are good-willed. “Uber has a long history of partnering with the taxi industry to provide drivers with more ways to earn and riders with another transportation option. Our partnerships with taxis look different around the world, and we’re excited to team up with taxi software companies CMT and Curb, which will benefit taxi drivers and all New Yorkers,” Andrew Macdonald, senior vice-president, Mobility and Business Operations, at Uber, said in a statement.

“After its business model has shown the failures to protect drivers from ridership downturns and rising gas prices, Uber is returning to its roots: yellow cabs.”

When I asked Mandeep what he thought about Uber partnering with the taxi industry, he said: “[I]f I can be frank, I am absolutely not for it…[T]he damage is done…we are talking six to seven years of loans for these medallions…hundreds and thousands of dollars of impact to people and livelihood lost…it is very, very late.” Mandeep said his father, with all his resilience, has already found ways to make his taxi career work (though he is not as successful as he once was). He would not be interested in partnering with Uber through taxi driving and does not see a benefit in it.

“Where does our accountability come in…when do we stand up to these corporations and massive organizations that have taken over our lives? The taxi medallion market and system in New York is one of the best, and it exists and is robust and operational…when we say that Uber is going to swallow these drivers, Uber ultimately wins.”

“You are essentially giving two entities (Uber and Lyft) massive power to control all drivers in the city of New York…I think that is pretty scary. I think a lot of taxi drivers are like we should have given Uber less power, and instead with these statutes and actions, we are giving Uber more power in the macro. We are essentially forsaking more regulation in this industry. As a student of this space, that is frightening,” says Mandeep.

The pursuit of profit does not consider the impact on the lives of real people. In the name of a bright new idea and disrupting new spaces, Uber destructed a sustainable path for immigrant families to achieve their American Dream. Uber also created a societal dependance on convenient, affordable rides that it is incapable of continuing to offer while also being profitable. To make matters worse, Uber is going back to the taxi industry that it spent years destroying and espousing as problematic, likely for the purpose of using the supply of taxi drivers and the existing relationships that taxis have with the city to drive revenue.

“I just fundamentally do not believe . . . a lot of new young immigrant families can do what my dad did with the way that the current Uber and Lyft system is set up.”

“We are grateful [that my dad] still has his house and we are grateful for where we are, but at the same time, the taxi world and the ways taxis operated prior to Uber and Lyft being there allowed for him to raise four kids and buy a house being a new immigrant to this country. I just fundamentally do not believe…a lot of new young immigrant families can do what my dad did with the way that the current Uber and Lyft system is set up,” says Mandeep.

When I asked Mandeep what he thinks his life would have looked like for him if Uber didn’t enter the market, I was heartbroken by the answer: “I imagine life would look a lot more wonderful for us. We would be in the middle class. My dad would feel a lot more confident about himself. I wouldn’t have to still be working to provide for my family…[T]hings would be very different.”