Gig Economy and the Future of Work

Uber & Lyft’s race to the bottom–an opportunity to redefine work

Shao Chang

July 11, 2022

Kevin found Lyft in 2013 after losing his job in the Recession. Initially, the job was exactly what it promised to be. The wages were good and he was able to spend more time with his daughter by only driving when she was in school. After a few months, Uber and Lyft recruited more and more drivers; and, once the hurdle of getting sufficient drivers was surpassed, the companies dropped their driver commissions.

In 2014, Uber claimed that UberX drivers working at least 40 hours a week made $90,766 a year in New York and $74,191 in San Francisco. A contemporaneous Washington Post article, comparing these numbers to the average $30,000 that cab drivers made in the same year, marveled at the “power of Uber” and its “mastery of technology.” Even in 2018, Uber was promising a $2,100 minimum in the first month of driving, and Lyft was promising a $2,500 minimum a month in Los Angeles.

A study by J.P. Morgan Chase & Co Institute found that, between 2013 and 2017, earnings from rideshare fell by 53 percent. The study attributed the decrease to the “rapid growth in the number of drivers” on the roads. Additionally, companies’ ever-changing compensation structure resulted in unpredictable but gradually decreasing wages. According to Adam, a rideshare driver, companies told drivers that the rate cuts would be a temporary promotion to entice more customers:

“They told us something like it was summer, and they were going to cut rates as a promotion for riders. And they just ended up keeping those rates. And then they did it again and again and again. Their explanation for drivers was: Hey, you get more rides, you get more money. Well, of course, if you work more, you make more. But you have to work like twice as much to make what you made before.”

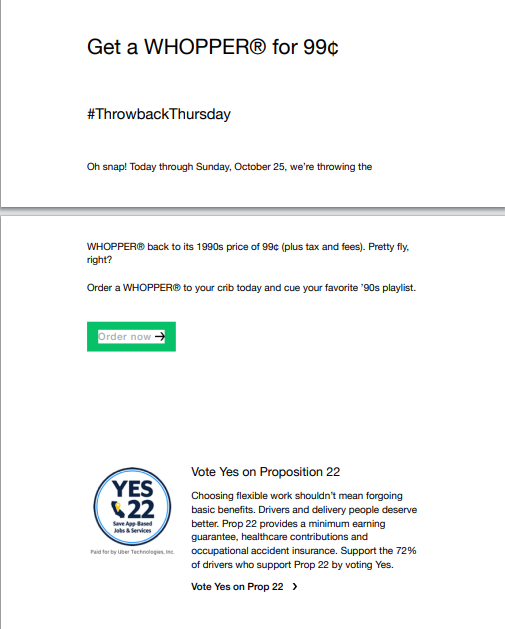

The change to upfront fares in 2016 did not help drivers either. Since their introduction, drivers have called what Uber has claimed to be a rate-transparency measure nothing but a maneuver to take a larger share of the profits. “They’re doing it to keep you in the blind, the driver in the blind,” said Michael, an original SideCar driver in 2017, “It seems like [the rider is] paying more, but it also seems like the driver is receiving less…. Uber [keeps] the difference.”

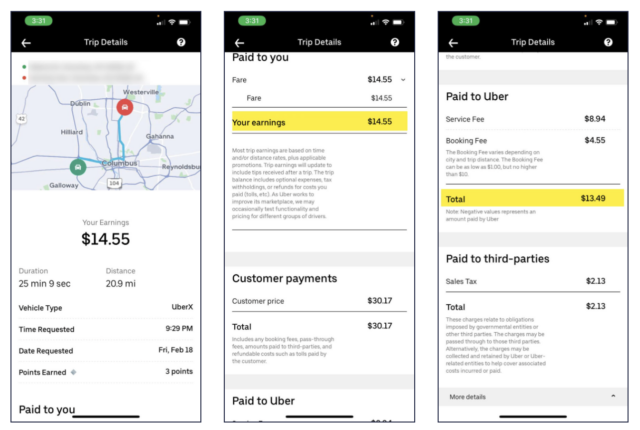

A change within the past two months in Uber’s algorithm decreased the transparency even further. The fares are based on “several [unspecified] factors.” A Columbus-based Uber driver, Vance shared two recent trips he made. On one $30-trip, he received $14 and $13 went to Uber. For another $22-trip, Vance received $6 and $9 went to Uber. The remainder went to fees and sales taxes. Although these are only two trips, this is a far cry from the 20 to 25 percent Uber had always claimed to take as a service fee.

Screenshots from an Uber trip in Columbus, Ohio, show how much the customer paid (center), how much the driver earned (left), and how much was paid to Uber (right). Source: Uber

Factoring in expenses–gas, insurance premiums, maintenance costs, and depreciation costs–the MIT Center for Energy and Environmental Policy Research has found that, on average, drivers make $661 a month. The authors also found that, after all relevant expenses were considered, 74 percent of drivers earn less than the minimum wage in their respective states, almost half of the drivers surveyed could legally declare a loss on their tax returns, and nearly 30 percent of drivers are losing money every mile they drive.

Although these findings are currently under revision to fine-tune the driver revenue used to calculate net profits (which Uber believes is too low of an estimate), these figures represent many drivers’ struggle to be profitable. Another study by the Economic Policy Institute calculates that, after Uber fees and vehicle expenses, a driver earns around $11.77 an hour. After deducting fees, vehicle expenses, and a modest benefits package, earnings fall to about $9.21 an hour.

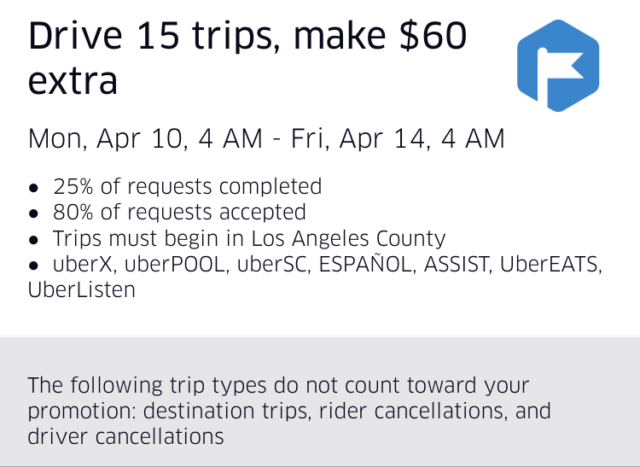

Some drivers recognize that driving depending on base fares alone is unsustainable. In response to a question about whether he could live without bonuses, promotions, and surge pricing, Adam responded, “Hell no.”

Some drivers recognize that driving depending on base fares alone is unsustainable. In response to a question about whether he could live without bonuses, promotions, and surge pricing, Adam responded, “Hell no.” He explained that “[i]f there’s no incentives, no bonuses, we would lose money. We would be forced to quit.”

Uber Quest example. Source: Uber, The Rideshare Guy

“The surge is psychological… It’s designed, it’s like Pavlov’s Dog,” Michael explains. “When a driver sees surge, they’re salivating.” Another driver explained his daily routine: “I’ll wake up in the morning. I’ll check my driver app to see if there’s any sort of surge in my area. And I’ll usually tak[e] a ride if it’s about a 2.0 surge.”

Drivers are dependent on higher fares to turn a profit, especially drivers that have financial need. Some become attuned to responding to surge pricing–a cue for where and when to drive. Even a study by Uber employees found that seeing a surge map attracts drivers to areas with surge pricing.

However, some drivers find the surge pricing off-putting for several reasons. First, the “fleeting nature” means that, by the time a driver arrives in the area, enough drivers may have satisfied the demand to eliminate the need for surge pricing. Surge pricing also may not last for very long for the same reasons. Lastly, being in the surge area does not guarantee that a driver will receive a ride from the surging neighborhood. Instead, drivers are attuned to when fares are generally higher, such as during rush hour or on Saturday nights, and they make their driving decisions based on this schedule.

Drivers are also reliant on tips to make up for the deficiency in pay. Articles, such as Slate’s “You need to Tip Your Uber Driver More Often,” ask customers to consider tipping Uber drivers since drivers cannot afford to live on such low wages. One driver shared that he depends on receiving around $100 a week from tips: “[a]s long as people give us tip, we okay.”

Not only are drivers chasing selective opportunities to make a profit, but many drivers are also tied to gig work since they are perpetually digging themselves out of setback after setback. Peter is “driving to pay his car-repair bills”–he spent $5,000 on repairs in six months, bought new tires, and was putting off the impending $23,000 he needed for a new car, as his current car was about to fail at any time.

Peter is “driving to pay his car-repair bills”–he spent $5,000 on repairs in six months, bought new tires, and was putting off the impending $23,000 he needed for a new car, as his current car was about to fail at any time.

Sakhr, an immigrant from Yemen, quit his job at Little Caesar’s for the promise of a higher paying job with Uber. Because his car did not meet the age requirements and out of fear that an older car would hurt his ratings, he bought a new Toyota Camry, putting him $25,000 in debt. “You think it’s going to be a great job, and it’s good, but it’s not as great as it sounds.”

He wants to go back to school but was driving to pay off his car and healthcare debt since he is able to work for more hours than a comparable job would allow.

Drivers are tied to the next ride, to the next surge pricing, to the new promotions, and to Uber and Lyft–all in the hopes of paying off expenses and making an income. If companies lower rates to bolster their bottom line, drivers have to work more to make up the difference.

Wages are also confusing because drivers are neither paid for their time waiting for a ride nor the time they spend picking up a rider. They also do not receive paid meal times or breaks. In other words, any hourly wage estimate is misleading as it does not represent the amount a driver can earn for each hour they are logged into the app–only the earnings per hour with an actual rider in the car.

__________

Thomas Liu, a former San Diego-based Uber driver, identifies as Asian and speaks with a slight accent. He says that riders often canceled requests after he accepted the ride and they could see his picture. He also reported that riders would also question where he was from in an unfriendly way.

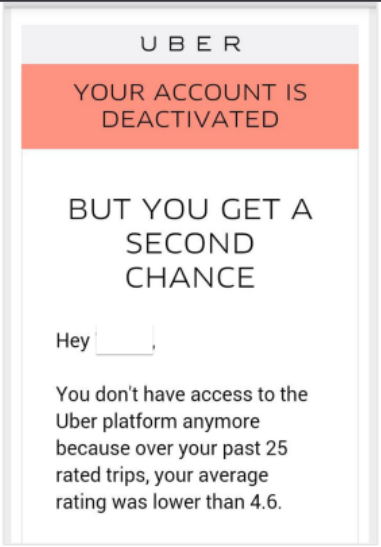

Sample deactivation notice. Source: Alex Rosenblat, K. Levy, Solon Barocas, & Tim Hwang, “Discriminating Tastes: Customer Ratings as Vehicle Bias”

Michael has been driving since the inception of rideshare and has built up a network of drivers. He reports the same with the drivers he knows: “the individuals who have the lowest ratings are . . . individuals where English is their second language.”

“the individuals who have the lowest ratings are . . . individuals where English is their second language.”

He notes that immigrants on the platform “are the ones that are most susceptible to the discriminatory potentiality of the system.”

Thomas Liu brought a lawsuit against Uber, alleging the star ratings had a discriminatory impact. During the hearing for Liu’s suit, the district court judge agreed that the research indicates online marketplaces tying employment to consumers’ ratings causes discriminatory results.

Michael believes that Uber should have been aware of the discriminatory impact of the rating system and pointed out that the reason why Uber initially disallowed tips was because of the bias involved in tipping. A working paper by the National Bureau of Economic Research confirmed this expectation. The researchers analyzed 40 million Uber trips and found drivers using the app in a different language received tips 30 percent lower than those using it in English.

Although not parallel, star ratings work in tandem with tipping for riders as a conduit to express their perception of the ride and the service. Drivers depend on every avenue of revenue to maintain positive earnings. By maintaining a system where drivers rely on tips, the rideshare companies are solidifying the role that bias plays in the driver-compensation system.

Not only do drivers face penalties such as deactivation and significantly lower earnings if their ratings are low, but they are also excluded from benefiting from perks that highly-rated drivers receive. Masked in merit, Uber Pro “recognizes outstanding drivers” who consistently maintain over a 4.85 rating through a point-system to unlock rewards, such as higher earnings per ride, 5 percent cash back at gas stations with an Uber Visa Debit Card, discounts on auto maintenance, free dent repairs, and so on.

Uber also reportedly offers select drivers the opportunity to participate in higher-earning shifts. Similarly, when drivers keep the “ driving score high” and drive when the need is the highest, Lyft offers highly-rated drivers exclusive features in the app, such as seeing additional trip details before accepting a ride and free or discounted auto expenses.

Rideshare companies not only incorporate rider bias into job security and earning potential through tips, cancellations, and ratings, but they also entrench the bias by conditioning further earnings and savings benefits on driver ratings. If drivers are not employees, employee antidiscrimination protection cannot protect drivers from this ingrained and encouraged discrimination.

__________

Introduced by then-Assemblywoman Lorena Gonzalez, California Assembly Bill 5 (AB 5) was hailed as an effort to correct the ongoing worker misclassification, that was benefiting companies and harming workers. “[W]e will not in good conscience allow free-riding businesses to continue to pass their own business costs on to taxpayers and workers,” Assemblywoman Gonzalez stated in her press release after the passage of AB 5.

AB 5 was meant to codify, clarify, and make uniform the California Supreme Court decision in Dynamex Operations West, Inc. v. Superior Court. Previously, the Court followed the Borello test, a multi-factor test considering specific factors and all relevant circumstances as spelled out in S.G. Borello & Sons, Inc. v. Dept. of Industrial Relations that produced non-uniform and unpredictable decisions. The Dynamex decision first introduced the ABC test for claims arising under a California wage order. The test established that to be considered an independent contractor, it must be established:

(A) that the worker is free from the control and direction of the hiring entity in connection with the performance of the work, both under the contract for the performance of the work and in fact; and

(B) that the worker performs work that is outside the usual course of the hiring entity’s business; and

(C) that the worker is customarily engaged in an independently established trade, occupation, or business of the same nature as the work performed.

AB 5 expanded the applicability of the ABC test, which became the default test under the California Labor Code and Unemployment Insurance Code. Although aimed at the California workforce generally, it was targeted at misclassification within the gig economy.

Many employers of independent contractors run into difficulty with prong (B) because their workers form an integral part of their business, including gig companies.