The jockeys and the hatters both quickly discovered the potential financial cost of asserting their dignity and challenging their employer’s treatment in federal court. Federal courts have long placed the weight of the law on the scales of justice in favor of the employer and against the workers, protecting power imbalances rather than correcting them.

However, the final chapter of the jockeys’ legal saga did not end with the district court ruling and neither was a national effort required to ensure the jockeys’ homes were not seized by the racetrack.

The jockeys appealed the adverse decision to the Court of Appeals for the First Circuit, which is the appellate court for federal district courts in Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Puerto Rico, and Rhode Island. In a major break with the prevailing judicial view, on April 4, 2022, the First Circuit reversed the district court’s decision and ruled in favor of the jockeys.

The First Circuit’s decision stands in sharp contrast to a history of federal courts’ animosity to organizing workers.

Early in its history, the courts turned the Sherman Antitrust Act into a “savage weapon” against working people trying to organize soon after the Act’s passage in 1890. For example, the judiciary used the Sherman Act to quell the Pullman strike in 1894, which led to the Supreme Court infamously upholding the conviction of Eugene V. Debs who organized in defiance of a court-imposed injunction.

“Under the influence of judges who had no personal knowledge of industrial affairs, no sympathy with workers in industry, and no understanding of the difference between property rights and personal rights,” the courts issued injunctions that “transformed the agencies of justice into engines of injustice and oppression.”

Federal courts also deployed the Sherman Act against New Orleans longshoremen organizing in 1892. The longshoremen organized Black workers, white workers, “printers, hearse drivers . . . musicians and carpenters” into a 20,000-person strike. Even though the federal judge recognized that “the congressional debates show that the statute had its origin in the evils of massed capital,” the judge still upheld the injunction of the organizers. There, the federal judge admitted that the court’s imposition of Sherman Act liability against organizing workers contradicted congressional history and intent.

“Origin in the Evils of Massed Capital”

On March 24, 1890, Senator John Sherman, after whom the Act was named, stated that “the combinations of workingmen to promote their interests, promote their welfare, and increase their pay if you please, to get their fair share in the division of production, are not affected in the slightest degree, nor can they be included in the words or intent of the bill as now reported.” Senator Sherman was explicitly clear on the legislation’s target:

“a new form of combination… called trusts, that seeks to avoid competition by combining… corporations, partnerships, and individuals… The law of selfishness, uncontrolled by competition, compels it to disregard the interest of the consumer. It dictates terms to the transportation companies, it commands the price of labor without fear of strikes, for in its field it allows no competitors.”

In this pronouncement, Senator Sherman raises the specific concern that monopolistic firms can command the price of labor without fear of strikes. Nevertheless, courts interpreted the act in service of those corporate entities in command of the price of labor and in fear of strikes.

As Congress debated the passage of what would become an economic charter of liberty, Senators raised the concern that the legislation’s text could be read expansively to apply to workers. The version of the bill’s language at that point banned any combination that raised prices to consumers and raising wages or providing better working conditions for workers could be framed as having the effect of raising prices.

Senator James George of Mississippi warned that the bill could be turned against “farmers and laborers.” Senator George raised the issue that the language could be turned against “‘workingmen’ organizing for better wages since increased wages may increase the price of goods.” Senator Vest raised a similar concern that “[e]very organization which attempts to take control of the labor that it puts into the market to advance its price is interdicted by this bill.” Senator Stewart likewise warned that “it is very probable that if this bill were passed the very first prosecution would be against combinations of producers and laborers whose combinations tend to put up the cost of commodities to consumers.”

However, Senator Sherman directly addressed these concerns, asserting that organizing workers “are not affected in the slightest degree, nor can they be included in the words or intent of the bill.”

The bill was amended twice, adding language exempting workers to clarify that it would not apply to combinations of workers trying to reduce hours or increase pay before it was referred to the Judiciary Committee. There, the statute’s language around consumer price – again, the key language that had driven congress members to warn that the bill might be read to cover labor – was removed. Only after this text was removed then, by extension, did the committee drop the labor exemption language.

Despite this history and the explicit target of the Sherman Act, courts imposed the antitrust law against workers exactly as the Senators forewarned, issuing injunctions against striking workers, disrupting labor organizing efforts, and holding workers liable.

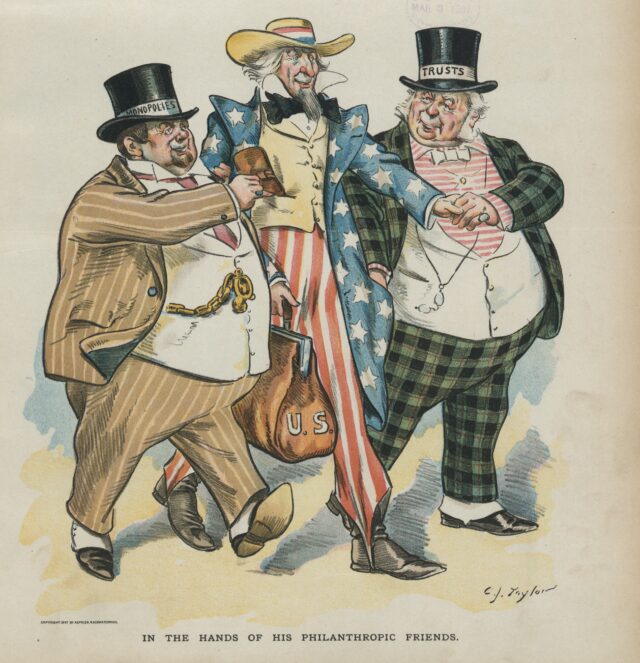

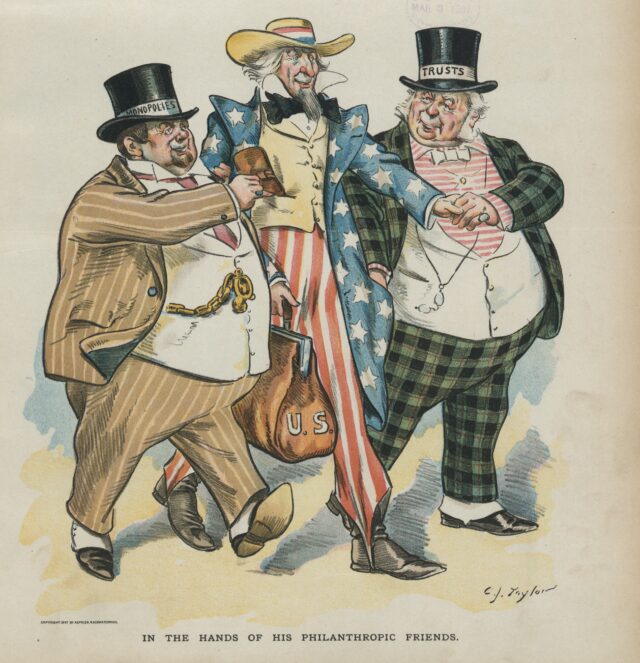

Source: https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2012647652/

Congress responded to the judiciary’s treatment of the Sherman Act, viewing the law as “tortured into a meaning” that transformed a law “intended for the relief of the plain people . . . into an instrument of oppression.”

Senator Hamlin asserted that “[u]nder the influence of judges who had no personal knowledge of industrial affairs, no sympathy with workers in industry, and no understanding of the difference between property rights and personal rights,” the courts issued injunctions that “transform[ed] the agencies of justice into engines of injustice and oppression.”

We are aiming at the dollars and not at men . . . Let us put the man above the dollar and exempt all associations of men for the betterment of their condition.”

Representative Graham of Illinois articulated the perceived imbalance of the courts who appeared to serve the interests of elites and employees, asserting that “[t]he acute struggle between organized wealth and organized labor has found its way to the courts, and there is some reason for believing that the courts, and more especially the Federal courts, consciously or unconsciously, have loaned too much to the side of organized wealth, to the side of property.”

By the 1910s, for members of Congress, it was clear that the legal system served elite, business interests and acted to subdue class discontent and workers’ attempts at building countervailing power. Congress’ outrage over the enforcement of antitrust laws through the judicial system drove the passage of the Clayton Act in 1914. Representative Thomas F. Konop described the intent of the legislation:

“We are aiming at the gigantic trusts and combinations of capital and not at associations of men for the betterment of their condition. We are aiming at the dollars and not at men . . . Let us put the man above the dollar and exempt all associations of men for the betterment of their condition.”

The federal courts’ misapplication of antitrust laws drove congressional animus and energized efforts to remove labor from the scope of antitrust enforcement.

Speaking in support of the Clayton Act, Senator Cummins elaborated:

“If we do not recognize the difference between the labor of a human being and the commodities that are produced by labor and capital … we have lost the main distinction which warrants, justifies, and demands that labor organizations coming together for the purpose of bettering the conditions under which they work, of lessening the hours which they work, and of increasing the wages for which they work shall not be reckoned to be within a statute which is intended to prevent restraints of trade and monopoly.”

Congress passed the Clayton Act with the profound proclamation that “[t]he labor of a human being is not a commodity or article of commerce.” The Act established protections for workers and expressly limited courts’ ability to impose antitrust injunctions on labor organizing and striking workers.

Despite congressional efforts, federal courts remained committed to the opposition of labor organizing. Federal courts read the Act’s labor exemptions so narrowly that they “effectively killed the Clayton Act by emasculating its basic labor exemption.” In 1930, one scholar concluded that the Clayton Act failed to prevent any injunctions from issuing under the Sherman Act as courts enjoined over 2,100 strikes in the 1920s.

The 1930 edition of the Annals of the American Academy of Political Science Foreword captured the discontent between the language of antitrust laws and the enforcement of the laws stating, “[s]ome regard them as the bulwark of industrial liberties, while others see them as a Procrustean bed to which only Labor is required to conform.” Although the antitrust laws were passed to advance industrial, economic liberties, captured legal institutions imposed the laws against labor organizing efforts seeking the realization of such freedoms.

Again, judicial system’s acts enraged members of congress. Congressman Fiorello LaGuardia denounced the “few . . . Federal judges” who had “willfully disobeyed the law.” He continued, “they emasculated it; they took out its meaning as intended by Congress; they made the law absolutely destructive of the very intent of Congress.”

In 1932, Congress passed the Norris-LaGuardia Act, broadly declaring that Act was aimed to restore “actual liberty of contract” to the “individual unorganized worker.” Section 104 of the Act expressly restriction courts’ capacity to issue injunctions against organizing workers.

The Act was passed explicitly to undo the courts’ narrowing of the Clayton Act’s labor exemption and expressly directs that the antitrust exemption for labor disputes applies “regardless of whether the disputants stand in the proximate relation of employer and employee.” Combined, the Norris-LaGuardia Act and the Clayton Act firmly established the statutory labor exemption, providing organized labor protection from antitrust liability.

The courts did not undermine the Norris-LaGuardia Act with the same contempt as it had with the Clayton Act. In United States v. Hutcheson, the Supreme Court recognized that the “underlying aim of the Norris-LaGuardia Act was to restore the broad purpose which Congress thought it had formulated in the Clayton Act but which was frustrated, so Congress believed, by ‘unduly restrictive judicial construction.’” However, the Supreme Court still narrowed the Act soon after its passage.

In Columbia River Packers Association v. Hinton, the Court excluded a group of fishermen from the labor exemption protections on the grounds that they were “independent businessmen” who went on strike over the price of the commodities (fish) they sold, not the price of their labor. Thus, the Supreme Court narrowed the labor exemption to exclude “independent businessmen, free from such control as an employer might exercise.”

Although this ruling does not apply to employees and unions that represent employees, courts would rely on this decision to exclude from the labor exemption a broad range of workers classified as independent contractors or gig workers even when they do not sell commodities.

While those classified as employees are protected to form unions, take collection action, and seek collective solutions, big businesses and employers have been enabled by the judicial system to use antitrust laws against workers classified as independent contractors or gig workers.

When the racetrack sent the letter reminding the Puerto Rican jockeys that they were independent contractors without the right to protection under the antitrust labor exemption, that was a threat to bring the force of the judicial system’s narrow interpretation down on the workers.

Reminding the jockeys to know their place, the letter “was a threat,” said Attorney Vizcarra Pellot.

For some scholars, such as Professor Samuel Estreicher, this is simply a continuation of judicial misapplication and misinterpretation since “[t]here is nothing in the Clayton Act or Supreme Court decisions on labor’s statutory antitrust exemption that hinges the applicability of the exemption on ‘employee’ status under federal labor relations law.” Regardless, this interpretation was the prevailing, dominant view among federal courts until the First Circuit’s ruling in favor of the jockeys.

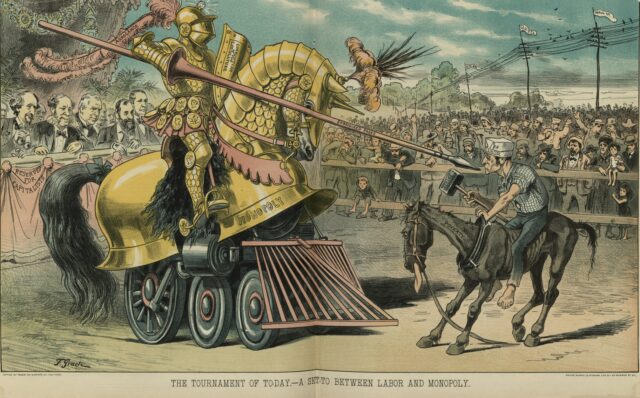

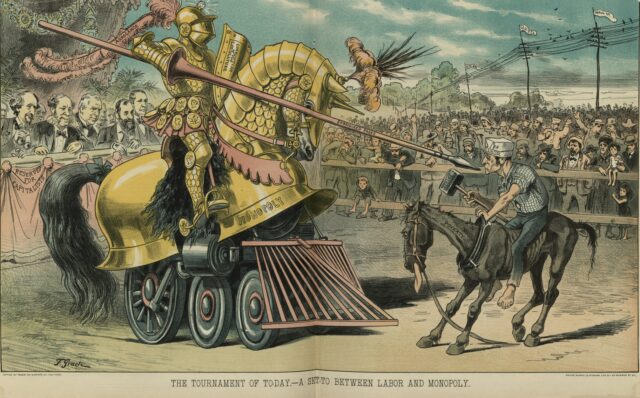

Source: https://www.loc.gov/pictures/resource/ppmsca.28412/

The First Circuit critically ruled that the jockeys’ concerted activity for better pay is exempt from antitrust liability. The court reviewed the intersection of the Clayton Act and the Norris-LaGuardia Act and concluded that antitrust law’s labor exemption protects strikes when they arise “(1) out of the actions of a labor organization and undertaken (2) during a labor dispute, (3) unilaterally, and (4) out of the self-interest of the labor organization.”

The court rejected the notion that independent contractors automatically commit an antitrust violation when they go on strike. Indeed, the judges held that the jockeys’ status as independent contractors is immaterial and noted that prior cases such as Superior Court Trial Lawyers Association had not directly addressed whether the labor exemption applies to independent contractors.

Instead, the Court held that the key question in deciding the applicability of the labor exemption is “whether what is at issue is compensation for [the workers’] labor.” Drawing boundaries around the labor exemption, the Court stated, “[d]isputes about wages for labor fall within the exemption but those over prices for goods do not.” Under the court’s decision, independent contractors can strike over wages and other terms of work without breaking the antitrust laws.

According to Vizcarro-Pellot, “The First Circuit clarified and put a stop to all the misconceptions of the precedent which have been used by courts to really oppress and keep workers at bay.”

On the sanctions imposed against the jockeys’ counsel, the First Circuit held that “[t]he record is barren of any findings to support the sanctions” and the “district court failed to explain on what basis it rested its authority to sanction [the jockey association] or its attorneys.”

Given the potential ramifications of the holding for worker power, the Chamber of Commerce filed a petition appealing the First Circuit ruling to the Supreme Court. The Chamber of Commerce’s interest in the case was cause for concern for the jockeys’ counsel.

Vizcarro-Pellot said, “Of course we had concerns. [The Chamber of Commerce] is one of the most powerful institutions in the United States going up against us and workers. But bring them on.”

The Chamber of Commerce’s petition framed the Circuit court’s decision as an impermissible, major break in accepted precedent—a precedent that has long ruled in favor of employers, not workers. Despite the interest groups attempt, on January 1, 2023, the Supreme Court denied certification, sustaining the First Circuit ruling for the jockeys in place.

“This case has been converted as a landmark decision,” said Porrata.

With the Supreme Court’s certification denial, the First Circuit’s holding is good law, ready to shield independent contractors from antitrust liability.

“The drum is beating and calls to action. Now [the decision] is in the record and waiting for the benefit of the people,” said Vizcarro-Pellot.

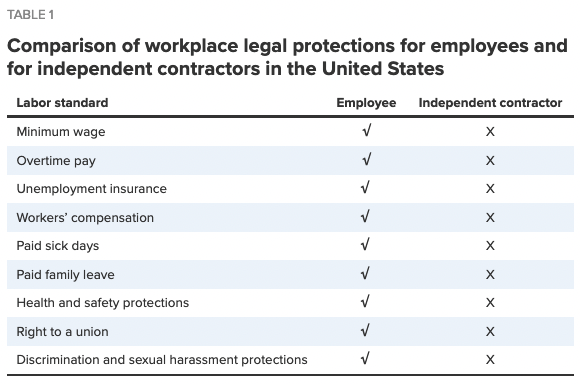

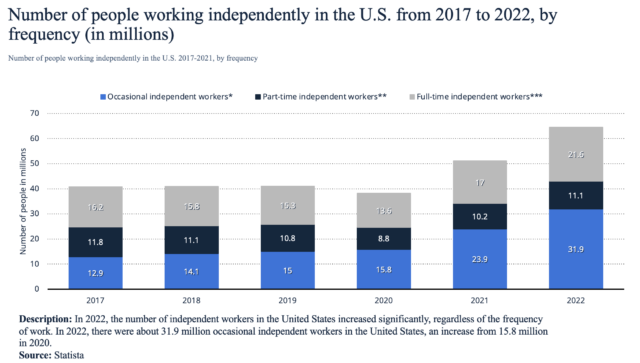

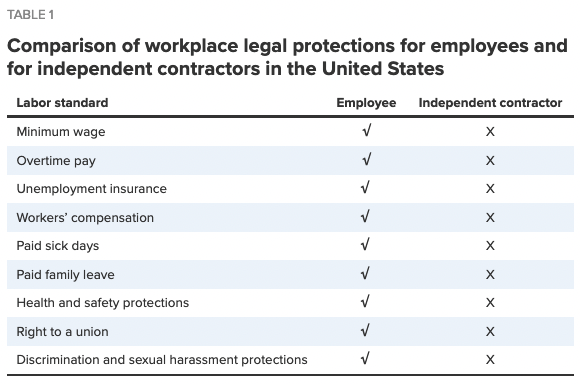

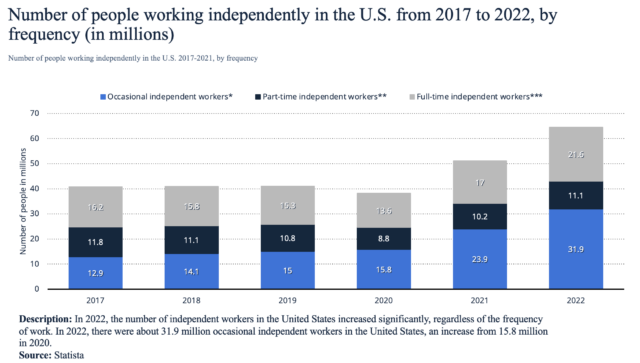

The legalization of certain strike activity for independent contractors is significant for the U.S. economy and U.S. employment law system in which corporations are permitted to classify, or rather misclassify, workers as independent contractors under federal law despite wielding employer-employee levels of control. For businesses, the distinction of employee versus independent contractor is critical to profit margins, cost-efficiency, and firm structure. For workers, the distinction is framed as benefiting financial freedom, flexibility, and independency but functions as a key determination for limitations on rights.

The independent contractor classification allows a company to avoid the obligations attached to employment like paying minimum wage, paying overtime, and providing benefits. And, until the First Circuit ruling, the independent contractor classification also ensured across the board that workers would not be able to exercise countervailing collective power to bargain for such pay and benefit obligations.

Source: Economic Policy Institute. Legal protections under federal law.

Although the notion of nontraditional, contract work based outside of the employer-employee relationship is not a recent phenomenon, the increasing number of workers classified as independent contractors and the prominent rise of gig-work platforms, such as Uber, DoorDash, Instacart, and TaskRabbit, give greater significance to how the law treats these workers. A national survey of independent contractors and gig workers reveals a picture of poor working conditions, low pay, and economic insecurity. The trend of hiring or misclassifying workers as independent contractors is disproportionately affecting lower paid and more dangerous jobs while rendering entire professions as impoverished fields of under-paid and under-protected workers.

While employment law allows corporations to wield control over independent contractors by dictating their prices, work operations, and wage without the legal responsibilities of employment, antitrust law is weaponized to ensure independent contractors endure the indignities, low-pay, and lack of control without the ability to join together to collectively negotiate and challenge their boss’ power. However, this status quo need not continue.

“Antitrust laws have a specific purpose, designed to exclude [from liability] workers who demand better pay and better labor conditions. It is not a question of controlling products but rather it is a question of controlling workers—it is about allowing workers to seek a better livelihood,” said Vizcarra Pellot.

Although the jockeys do not expect the racetrack and horse owners to capitulate to their demands without further disputes, the jockeys have leverage in their collective resolve and countervailing bargaining power to seek their first wage increase since the 1980s. They hope to earn an increase by early 2024.

The First Circuit’s ruling is one necessary step of many towards progress, opening the door for workers beyond the jockeys in Puerto Rico to organize and build power.

“Litigants and litigators should use this ruling to make justice for a lot of workers classified as independent contractors that are just abused by the power of companies.” Vizcarra Pellot continued, “It provides a tool for [independent contractors] to really fight back despite not having a union. As long as they follow the case, they have a shot at making a better living rather than being exploited.”

In Puerto Rico, 37 independent contractors refused to bend to the monopolistic power of their bosses. 37 workers refused to quietly endure the abuse and threats that are so regularly imposed. 37 jockeys fought to recognize their labor rights and won.

“37 jockeys can change the world and make history,” said Vizcarra Pellot.