Denial and Defense: The NFL’s Greatest Play

A look into the playbook that industry scientists used to generate profit for corporations

Deepika Singh

September 27, 2023

“The Autopsy that Changed Football”

As 2002 stretched to a close, the Pittsburgh Steelers battled game after game at Heinz Field while the brain of NFL star Mike Webster lay in a condo just miles away. Webster’s brain tissue rested on a cutting board next to a microscope and knife after having been transported in a plastic tub to Dr. Bennet Omalu’s home in the small borough of Churchill, Pittsburgh. For months, the physician woke up at 2 A.M to pore over images of Webster’s brain slivers, even paying for dozens of microscope slides out-of-pocket. What he discovered late one night in Webster’s brain would catalyze years of research on concussions, spur book deals, and propel his name into headlines all over the country. Dr. Omalu’s examination of Mike Webster’s body would soon be known as “the autopsy that changed football.”

![]()

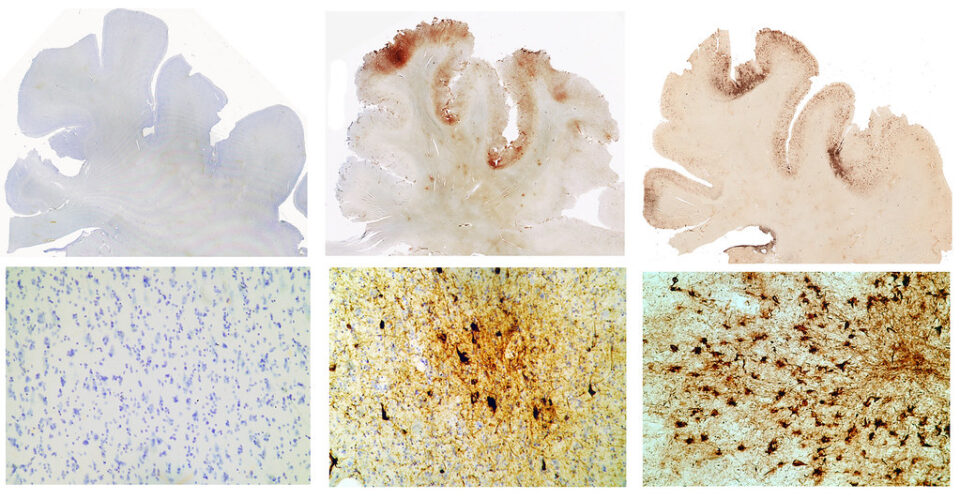

In Webster’s brain tissue, Omalu encountered a progressive and fatal disease no one had ever seen before; one in which buildups of a protein called “tau” form clumps in the brain called neurofibrillary tangles. These clumps kill healthy cells that regulate “mood, emotions and executive functioning.” After consulting his colleagues, Omalu published his research in a top science journal Neurosurgery, titling his paper “Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy in a National Football League Player.” The paper detailed a disease now commonly known as CTE amongst serious scientists and football fanatics alike.

Omalu thought NFL doctors would embrace his startling discovery on catastrophic brain injuries sustained by professional football players and use it to enhance the safety of athletes that generate billions of dollars in revenue every year. “I thought they were gonna call me and embrace me and say, ‘Motherf*cker, you’re such a hero,” he remarked. Soon, Omalu would realize how naïve his sentiment was.

Dr. Omalu’s examination of Mike Webster’s body would soon be known as “the autopsy that changed football.”

Rather than thank Omalu for his CTE discovery, the NFL adopted an insidious playbook that corporations have executed repeatedly for decades: the league denied the allegations, dismissed the research, and generated doubt with alternative studies.

In the weeks following Dr. Omalu’s publication, the NFL pushed for retraction of his paper. However, this attempted obfuscation couldn’t triumph against the mounting evidence of head trauma in retired pro-footballers. Michael “Iron Mike” Webster had not been the only football player with a progressive brain disease. Terry Long, Andre Walker, Justin Strzelczyk: Just like Webster, these players’ bodies donned the black-yellow uniform of the Steelers during their lives, and just like Webster, their brain tissue bore the brown-red splotches of irreversible CTE after their death.

![]()

In 1994, NFL commissioner Paul Tagliabue realized that outright denial of the link between football and brain damage was no longer a winning strategy; there was too much evidence pointing to the contrary. He cobbled together the Mild Traumatic Brain Injuries (MTBI) Committee, a research group with a mandate “to scientifically investigate concussion and means to reduce injury risks in football.” This seemingly innocuous committee was stacked with many doctors and experts who had financial ties to the NFL.

Equipped with the legitimacy of the MTBI, the League executed step-by-step the same playbook that Big Tobacco had used decades prior, and that meat, dairy, chemical, and oil industries are carrying out today:

Rather than thank Omalu for his CTE discovery, the NFL adopted an insidious playbook that corporations have executed repeatedly for decades: the league denied the allegations, dismissed the research, and generated doubt with alternative studies.

First, they denied the connection between football and brain injuries by delegitimizing Omalu’s initial damning study, citing “serious flaws” and “complete misunderstanding.”

Second, they pumped out their own research, using biased science and motivated reasoning to affirm the findings most favorable to them. In the years following its genesis, the MBTI committee published 16 papers in the Oxford Journal of Medicine’s book on the brain, Neuropsychology. Study after study minimized the danger of head trauma in football players who continue to compete after suffering concussions.

Lastly, having sown enough doubt about CTE, they sat back and cashed in on revenue at the expense of the Terry Longs, Andre Walkers, and Mike Websters of the league.

Frontal cortex slides from CTE study. From Left to Right:

(1): A normal brain from a 65 year old

(2): The brain of a former NFL linebacker, John Grimsley (who suffered 8 concussions and died at age 45)

(3): The brain of a 73 year old boxer who suffered from an extreme form of dementia pugilistica

Credit: https://www.flickr.com/photos/wbur/2984426778. WBUR Boston

The Playbook

The NFL’s strategy to discredit unfavorable scientific research is not an original one. The league’s instinctual reaction of denial and defense when faced with profit-threatening science runs deep in the hidden disposition of almost every corporation spanning across the decades.

The giants at the top of corporate structures are bound by one goal: generate profit for stakeholders. This goal is threatened when emerging evidence suggests that certain products and behaviors of the corporation inflict damage upon society and the environment. Corporations evade liability by enlisting dozens of “specialists” to undermine the evidence, confuse the public, and prolong regulatory action. At a moment’s notice, companies are able to hire toxicologists, physicians, epidemiologists, attorneys, public relations specialists, and other experts required to produce reports favorable to the corporation.

Dr. Bennet Omalu remembers one encounter with a prominent NFL physician shortly after publishing his groundbreaking paper on CTE:

“…the NFL doctor at some point said to me, ‘Bennet, do you know the implications of what you are doing?…Your work suggests that football is a dangerous sport, and if ten percent of mothers in this country would begin to perceive football as a dangerous sport, that is the end of football…’”

Faced with the looming possibility of declining profit, the NFL became “merchants of doubt”, a term coined by epidemiologist and professor David Michaels. Michaels devotes his career to exposing the product defense industry – companies and experts whose purpose is to use bad science to produce favorable results to corporate giants. Using the same playbook, the product defense companies sow doubt and confusion about the hidden dangers of corporate activities.

The Playbook to Manufacturing Doubt:

A flattened carton of Marlboro cigarettes, an American brand of cigarettes owned and manufactured by Philip Morris

Credit: Photo by Giorgio Trovato from Unsplash

STEP ONE: Denial – Tobacco

By the time NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell was being questioned in front of the House Judiciary Committee on October 28th, 2009, step one of the playbook was already fifteen years in motion.

For 15 years, the MBTI Committee had been countering and denying the evidence establishing the link between football and brain-injuries. The Committee’s function was to confuse the public about the dangers in the football industry.

Yet, evidence suggesting otherwise mounted through the years, and a frustrated Congress finally summoned Goodell to testify about cognitive impairment in retired NFL players.

Present at the day-long hearing were lawmakers, former players, and former team executives. Mr. Goodell remained evasive when pressed on whether he thought football collisions lead to cognitive decline in his NFL players.

Referencing the MBTI Committee, Goodell asserted defensively, “We have published every piece of data in the N.F.L. We have published it publicly, we have given to medical journals, it has been part of peer review. We don’t control those doctors. They are medical professionals. They’re scientists. They do this for a living.”

Goodell’s defense ignored a glaring truth. Even in its conception the MBTI was shrouded with controversy: Rather than turn to independent, renowned researchers and doctors, then-Commissioner Paul Tagliabue inserted staff members that puzzlingly lacked expertise of the brain. The committee was lead not by a neurologist, but a rheumatologist with no background in brain research. Much of the MBTI staff also had financial ties to the NFL and to specific teams; Tagliabue had flooded the committee with representatives from the NFL Team Physicians Society, the Professional Football Athletic Trainers Society, and NFL equipment managers.

“much like the tobacco companies, the NFL had used its power and vast resources to try to discredit scientists it disagreed with and bury their work, cherry-picked data to make selective arguments about concussions, and elevated its own flawed research.”

The fact that doctors with financial ties to the NFL might have ulterior motives to protect the sports league was not lost on Los Angeles Democrat Linda Sanchez. Her emphatic words voicing this concern rang through the packed hearing on that October day in 2009:

“I’m a little concerned that the NFL sort of has this kind of blanket denial or minimizing of the fact that there may be this link. And it sort of reminds me of the tobacco companies pre-1990s.” When Goodell spoke of research refuting any connection between brain trauma and football players, Sanchez fought back, “You are talking about one study, and that is the NFL’s study. You are not talking about the independent studies that have been concluded by other researchers.”

This nightmare comparison with Big Tobacco is one the NFL would have trouble fighting off in the years to come; the similarities were evident. As the book League of Denial highlights, “much like the tobacco companies, the NFL had used its power and vast resources to try to discredit scientists it disagreed with and bury their work, cherry-picked data to make selective arguments about concussions, and elevated its own flawed research.”

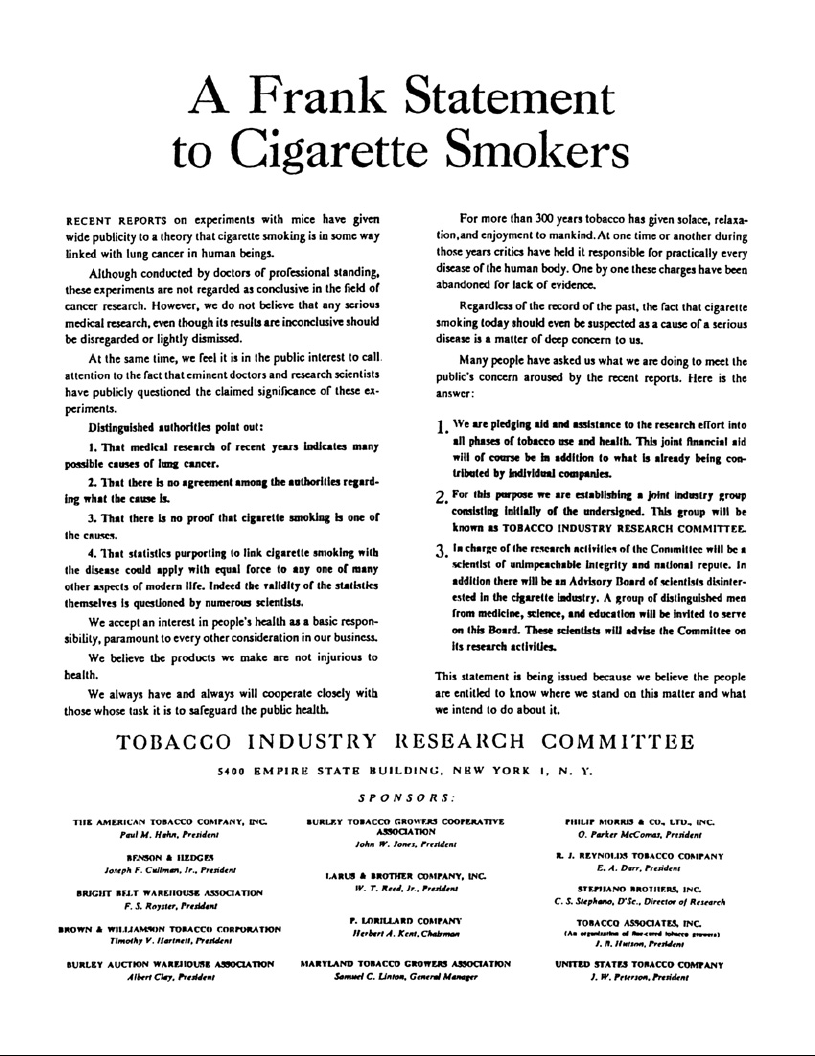

![]()

What the MBTI was for the NFL, Hill & Knowlton did for the tobacco industry. When corporations are confronted with bad press and potential lost profits, they often need to recruit outside help to deny the unfavorable science. Clothed with the authority of their degrees and credentials, toxicologists, epidemiologists, scientists and PR experts all work together to produce favorable evidence for corporations under threat of declining profits and incoming lawsuits.

In 1953, the public was just awakening to the dangers of smoking and tobacco stocks started steadily declining. Alarmed by this trend, six leading cigarette makers called for “drastic action” and held a historic secret meeting with the public-relations firm Hill & Knowlton. Under the recommendation of Hill & Knowlton, the manufacturers formed the Tobacco Industry Research Committee and mandated the committee to “aid and assist research into tobacco use and health, and particularly into the alleged relationship between the use of tobacco and lung cancer…” Just like the MBTI for the NFL, the Tobacco Industry Research Committee published pro-corporation articles and studies to counterattack the negative press they were facing.

The articles boasted titles such as:

“Go Ahead and Smoke Moderately”

“Phony Lung Cancer Scare”

“Who Says Smoking Gives Men Lung Cancer?”

“Smoke Without Fear”

In a dual-hit maneuver, the Tobacco Industry Research Committee both endorsed smoking and also criticized anti-smoking science by “bombarding” them with skeptical language:

“Fails to support . . . tenuous and inconclusive . . . still quite obscure . . . little evidence at present . . . no clear picture has emerged . . . lacked adequate controls . . . misdiagnosis . . . still no assurance . . . lend little to support . . . did not sustain any claims . . . suggest attention to the smoker rather than the smoke . . . speculative . . . baffling . . . superficial . . . unanswered . . . masked . . . overdiagnosis . . . fictitious . . . does not duplicate real life situations . . . still little is understood . . . many anomalous and contradictory aspects . . . no firm evidence . . . problems of diagnosis and nomenclature . . . misstated or overstated . . . an impressive failure . . . still remain to be explored . . . cannot be concluded . . . dubious accuracy . . . confusion of contradictory findings . . . welter of fragmentary, confusing and inconclusive observations.”

This language mirrors that used by the NFL-founded research committee when discrediting Dr. Bennet Omalu’s initial findings of CTE:

“we disagree…serious flaws…complete misunderstanding…”

By casting doubt on the accuracy of existing studies, both the MBTI and the Tobacco Industry Research Committee successfully executed step one of the playbook and manufactured what appears to be reasonable skepticism about the dangers of the industry.

STEP TWO: Deceit – Sugar

Though step one of the playbook is a counterattack, step two is more proactive: generate “bad science” that is favorable to the corporation.

When questioning Goodell in the 2009 hearing, Rep. Linda Sanchez chose Big Tobacco as the analogy to criticize the NFL’s behavior. Yet, the corporate strategy of denial and defense actually predates Big Tobacco to another giant industry who knowingly deceive consumers: sugar corporations.

Advertisement published in response to evidence that smoking causes lung cancer

Credit: [source: Tobacco Industry Research Committee – http://tobaccotimeline.files.wordpress.com/2012/01/frankstatementimage815.png]

Hockett had been the former chief of the Sugar Research Foundation (SRF), the scientific arm of the sugar industry (think MBTI and the NFL, or Tobacco Industry Research Committee and Big Tobacco). The Sugar Research Foundation was formed to investigate the emerging science that suggested sugar caused diabetes, tooth decay, obesity, and vitamin deficiencies, among other diseases. Yet, just like other industry-funded committees that conduct “research”, the SRF ran a disinformation campaign that manufactured doubt on profit-threatening science.

In his letter to tobacco executives, Hockett aggressively marketed himself by listing his previous work for sugar companies and noted the comparison between the sugar and tobacco industries. He boasted, “I organized and directed research projects …which exonerated sugar of most of the charges that had been laid against it…I am tempted now to suggest that my experience and background may be useful to the new Tobacco Industry Research Committee.”

Cigarette executives quickly hired Hockett to apply his framework for the sugar industry, now on behalf of the tobacco industry. The techniques the sugar industry used to cherry-pick data and generate dishonest science were many. The industry spent a fortune directing attention away from sugar into fats, or pumping out the myth that sugar consumption was easily counteracted by exercise.

Perhaps the most successful industry-sponsored science was that produced by Coca-Cola. The beverage giant shoveled money to scientists and university professors that declared Coke consumption had no deleterious effects on human health. Joined by Pepsi-Co, Dr Pepper, and other beverage companies, Coca-Cola funded sugar studies that flooded academic journals – the same sorts of journals that the tobacco and football industries would publish in years later.

This deceit tactic foreshadowed the playbook that Big Tobacco and the NFL would execute. As epidemiologist David Michael’s notes, “Although Big Tobacco is now the iconic industry for the dishonest use of science, Big Sugar’s subterfuge actually predates that of the more notorious industry. It can now be plausibly argued that rather than merely imitating Big Tobacco’s game plan, it was in fact Big Sugar that provided the first full-scale model.”

STEP THREE: The Waiting Game

Credit: [Source: Chris Leboutillier/Unsplash]

It’s been eighteen years since Bennet Omalu first published the paper based on the discovery he made in the living room of his condo in Churchill, Pittsburgh. In this time, seventeen seasons of professional football have been played, generating over 100 billion dollars in revenue. Dozens of players have been inducted into the NFL, and thousands of middle-school and high-school college kids have picked up the game that Mike Webster started playing at 16.

Yet, no other profession outranks professional football in terms of causing life-altering injuries.

In 2011, professional NFL player Shane Dronett shot himself in his house, leaving a final request on a handwritten note: “Please, see that my brain is given to the N.F.L. brain bank.”

Chargers linebacker Junior Seau shot himself in the chest in his home in San Diego at the age of 43. The National Institutes of Health would declare a year later that his brain showed “cellular changes consistent with CTE.”

In 2017, Patriot’s player Aaron Hernandez hanged himself with a bedsheet in a Massachusetts prison at the age of 27, after being charged with first-degree murder. For months, Hernandez had struggled with impulses for aggression, rage behavior, and emotional volatility. Researchers at Boston University revealed that Aaron Hernandez “suffered the most severe case of chronic traumatic encephalopathy ever discovered in a person his age.”

It took eleven years from the publishing date of Omalu’s paper for the NFL to finally concede there was a connection between football and the degenerative brain disorder CTE. But for victims like Dronett, Seau, and Hernandez, it was already too late.

Football Jersey worn by Mike Webster for the Steelers (right)

Source: Wikimedia Commons

During Roger Goodell’s hearing in front of the House Judiciary Committee, American neuroscientist Christopher Nowinski spoke on behalf of past and future victims of NFL’s corporate denial and defense strategy:

“So much of this crisis has mirrored big tobacco and the link between smoking and lung cancer. And I ask you if you were able to create all the smoking laws and awareness we have today back in the 1950’s when the first conclusive pathological research was done linking smoking to lung cancer, would you save those millions of people who smoked without understanding the risks?…the choice these men made to play football was made when they were just children…think about what you are willing to do to ensure this doesn’t happen to future generations.”

Eventually, even tobacco executives couldn’t deny the causal relationship between smokers and lung cancer. But the irreversible damage had already been done. Since a “Frank Statement to Cigarette Smokers” was published, an estimated 18 million Americans have died from smoking-related causes.

After denying the research and generating doubt in the public with dishonest science, in the third step of the playbook, industry giants sit back and rake in revenue. By the time the corporation’s studies are debunked, it’s already too late for the consumer. The product defense campaigns buy the corporations enough time to thrive while sowing irreparable damage in society. In the case of CTE, doctors explain, “these men are damaged beyond repair: no cast, no surgery, no medicine, no rehab can change their fates.”

As for the product defense industry?

They simply move on to the next disingenuous play. David Michaels grimly explains, “There’s always another opportunity to manipulate the vulnerabilities at the intersection of science and money.”

Some companies like The Weinberg Group or Exponent Inc. exist just to produce litigation documents and deceptive studies for corporations to present to judges and juries. The Weinberg Group, who defended Big Tobacco, later served DuPont when whistleblowers revealed a toxic compound used by DuPont to produce Teflon contaminated drinking water. Exponent, the company that denied the link between secondhand smoke and lung cancer, was hired to investigate Deflate Gate in 2014. These companies recycle the playbook over and over skillfully, exiting industries when the lies are no longer plausible, and entering new ones where the grounds for generating doubt are fertile.

There’s always another opportunity to manipulate the vulnerabilities at the intersection of science and money.”

So what can be done to prevent the public from this phenomenon of deceit by the product defense industry? David Michaels provides the first step of safeguarding our health and environment: “We must ensure the production and application of the best science possible, produced by independent, unconflicted scientists.”

Michaels suggests we can protect society from corporate manipulation through measures such as mandating complete disclosure of funding for scientific studies, having unconflicted scientists decide what the evidence means, and spreading awareness of the corporate playbook on manufacturing doubt. He posits that it is only when regulation curtails corporate malintent that we can live in a society that is free of looming health and environmental degradation. Indeed, the lives of the Mike Websters of the world depend on it.

![[F]law School Episode 9: Profits Over Patients](https://theflaw.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/danie-franco-CeZypKDceQc-unsplash-scaled-e1735518825718-640x427.jpg)