As migrant children await placement in an immigration system that routinely stalls and breaks down, the unaccompanied minors become a vulnerable labor pool desperate for work to support themselves and their families abroad. Their age, economic need, and immigration status make immigrant children targets for labor traffickers and labor brokers. For example, PSSI allegedly relied on local labor brokers and staffing agencies in towns with large numbers of immigrant children. However, the employment of migrant children is not unique to PSSI.

Blame-Shifting and Constructing Barriers to Accountability

Through this fissured work structure, companies insulate themselves from accountability. Corporations can both condemn child labor broadly and do little to specifically address their corporate arrangements that produce it while also shifting the narrative down to focus only on the lower-tier staffing agency and labor broker. Blame-shifting thus becomes an essential feature of the organizational scheme—corporations achieve cost control and impose exacting production schedules while performing a willful ignorance as lower-level contractors cut corners and do whatever it takes to meet their objectives.

None of the major processing companies who contracted PSSI received fines alongside the cleaning service. In response to the investigation and subsequent fines, the major companies followed a typical script: denounce child labor and shift-blame downward to the contracted intermediary, PSSI.

Michael Koenig, chief ethics and compliance officer at JBS USA, said “JBS has zero tolerance for child labor, discrimination or unsafe working conditions for anyone working in our facilities. We expect and contractually require our partners to adhere to the highest ethical principles as outlined in our business associate code of conduct.”

Tyson Foods took a similar stance as Dan Turton, a senior vice president at Tyson, wrote in a letter to members of Congress about their child labor concerns, “Tyson Foods is committed to compliance with all labor laws and holding those we do business with to the highest standards of accountability.”

PSSI also followed a similar script: condemn child labor and shift-blame downward to individual actors as bad apples.

“Our company has a zero-tolerance policy against employing anyone under the age of 18 and fully shares the DOL’s objective of ensuring full compliance at all locations,” said a spokesperson for PSSI. Placing blame elsewhere, a PSSI spokesperson stated, “While rogue individuals could of course seek to engage in fraud or identity theft, we are confident in our company’s strict compliance policies and will defend ourselves vigorously against these claims.”

However, contrary to the PSSI statements, according to Wage and Hour Regional Administrator Michael Lazzeri in Chicago, the “investigation found Packers Sanitation Services’ systems flagged some young workers as minors, but the company ignored the flags. When the Wage and Hour Division arrived with warrants, the adults – who had recruited, hired and supervised these children – tried to derail our efforts to investigate their employment practices.”

In an interview with Adam Benforado, law professor at Drexel University Kline School of Law and author of A Minor Revolution: How Prioritizing Kids Benefits Us All, he said, “The script is simple but effective. It is easy to accept narratives of a few bad apples and so a company will pawn this blame off on evil actors as low on the food chain as possible so that the company itself is not implicated.” Benforado continued, “But the compelling story only targets a few bad apples, such that it is framed not as a system problem but as an individual actor problem. There is nothing broken in corporate law. There is nothing broken with the structure of private contractors. At most, maybe this one particular sanitation company will be framed as bad, but the underlying structures and systems that incentivized that company remains invisible.”

For the meat processing companies who own the facilities in which children as young as 13 were cleaning dangerous equipment with hazardous chemicals and working overnight, this is a story of a rogue contractor. For PSSI who employed the children and put them to work in these conditions, this is a story of rogue individuals. Ultimately, only PSSI faced fines. None of the major meat processing companies were punished.

“External auditors are also in the business of profit maximization. They are not in the business of catching labor violations.”

Although the meat processing companies cut ties with PSSI, the system and incentives remain the same. More recently, in February 2024, a second major slaughterhouse cleaning company was found by the Labor Department to have employed children. According to the DOL, Fayette Janitorial LLC illegally employed 15 children to clean a Perdue Farms poultry processing plant and 9 to clean a Seaboard Triumph Foods pork processing plant in Iowa. Similarly to the PSSI incident, children were employed to work overnight shifts using dangerous chemicals to clean killing floor equipment such as head splitters, jaw pullers, meat bandsaws, and neck clippers. At least one 14-year-old at the Perdue facility suffered severe injuries while employed by Fayette.

Despite the lack of direct accountability at the time of the PSSI investigation, in September 2023, the DOL opened specific investigations into child labor practices in the slaughterhouses of Tysons Foods and Perdue Farms—companies that account for one-third of chicken sold in the US. Among legal practitioners, the probe has been described as “unique,” reflecting the rarity of investigating major companies for the illegal acts of their subcontractors.

Source: Industrial Workers of the World.

The Limitation of Shareholders as Check on Corporate Practices

Following the typical script of condemnation and blame-shifting, a spokesperson for Perdue responded to the probe, stating that the company has “strict, longstanding policies in place for Perdue associates to prevent minors from working hazardous jobs in violation of the law” and announced the company was “conducting a comprehensive third-party audit of child labor prevention and protection procedures including a compliance audit of contractors.”

For Tyson Foods, a shareholder similarly proposed a third-party audit of labor practices within the company’s supply chain and asked the company to disclose more information detailing how it is making good on their stated no tolerance policy for illegal child labor. The proposal highlighted the fact that the Company does not disclose information on how its commitment to its no tolerance policy for the use of illegal child labor is implemented. Through a proxy statement, Tyson responded that the company has already “strengthened its policies and practices” including “a robust system of checks and audits.”

On February 8, 2024, headlines announced shareholders had rejected the proposal. For some observers, this result may seem like a democratic outcome in which shareholders came together to voice their interests for what is best for the company. However, Tyson has a dual-class stock structure in which insiders and Class B shareholders hold 10-votes-per-share stock while Class A publicly traded shares only have 1-vote-per-share stock. As a result, Tyson Limited Partnership (TLP) controls 70.63% of the company’s voting stock. Under this structure, there is effectively no chance of a majority vote opposed by management.

“But the compelling story only targets a few bad apples, such that it is framed not as a system problem but as an individual actor problem.”

“When we talk about shareholder primacy, we are not even talking about all shareholders. We’re really talking about the wealthiest of the wealthy—a very small subset of shareholders who really control American companies.” Benforado continued, “Even where shareholders think a practice is bad for society, controlling shareholders will still win.”

Among the Class A shareholders who only own publicly traded stock, the proposal to audit the companies labor practices received 52.32% of the vote. Despite this majority, the proposal still failed because of the dual-class stock structure.

“The vote shows again the weakness of shareholder as a check on the most powerful entities in society’s worst instincts,” Benforado said.

The shareholder proposal did not present radical reforms for the company, but rather, the proposal was only for disclosure of Tyson’s employment policies pertaining to child labor and a third-party audit. Third-party social compliance audits have become a norm in corporate governance. However, the use of these audits may increasingly prove self-serving. In addition to the deployment of work structures and intermediaries for insulation from accountability, companies have increasingly turned to private industry for self-regulation as an alternative to accountability arising from public institutions.

Private Markets for Self-Regulation: The Capture of Third-Party Auditors

Third-party audits are increasingly deployed and relied on by corporations as a privatized policing mechanism. The demand for third-party audits has created an $80 billion global industry in which firms perform hundreds of thousands of inspections every year. However, a recent New York Times review of confidential audits conducted by several large firms in the audit industry has revealed a captured private enforcement market that consistently misses child labor incidents.

Within the compliance audit industry, private auditors face barriers and disincentives to providing truthful and robust accounts of business practices.

The companies themselves can dictate the scope of the audit, determining when and where auditors conduct inspections as well as what documents the auditors review. Facility inspections are typically scheduled weeks in advance with auditors reporting that they avoid arriving earlier than scheduled as to not risk upsetting the factories.

“They know auditors don’t come back to see if the lights are on at the meatpacking plant at 3 a.m,” said Doug Cahn, a corporate compliance advisor who created the audit system for Reebok International. “If you tell them when you’re showing up, they can game it.”

Under these conditions, auditors can miss the shifts in which minors are employed or inspect facilities or parts of supply chains in which children do not work. During inspections, auditors may not have the opportunity to speak to employees at the job site. And, even where auditors can speak with workers directly, fear of retaliation and lack of translation services may prevent the truthful disclosure of worker experiences. Further, sub-contractors are rarely ever placed within the scope of compliance audits. Research has also found that third-party audits regularly rely on forged or false documents.

Auditors report being encouraged and pressured to have a light touch, limit their inquiries, and deliver favorable findings. Auditors experience multiple sources of influence that can skew the results of inspections—whether it be from the independent audit company that pays their salary, the corporations that impose the inspections on suppliers and lower-tiers on the supply chain, or the facilities themselves that often arrange and pay for the service. In fact, research has found that auditors report fewer violations when factories or facilities are paying for the audit service. Financial conflicts of interest define the private market of independent, third-party auditors.

“External auditors are also in the business of profit maximization. They are not in the business of catching labor violations. Companies want a clean bill of health and auditors want to maintain positive business relationships,” said Benforado.

“What these bills are seeking to do is to legalize the violations that they’re already committing in these industries.”

The Times’ review found that auditors regularly certified facilities as free of child labor but acknowledged in their reports that they could not attest to the truth of the determination. The review also included a specific investigation of one particular company, UL Solutions, which directs its auditors in the employee handbook that “The assessment is not meant to be a policing effort.”

According to UL Solutions, an audit “cannot and does not guarantee that an audited facility is in full compliance with requirements against which it was audited, and does not confirm or certify compliance with laws.”

However, despite these disclaimers relinquishing the guarantees of compliance, major companies adorn themselves with third-party audits as proof of their law-abiding stature and signal their commitment to certain social responsibilities such as commitments against the use of child labor.

“For companies, the beauty of the third-party audit is also that it reduces the apparent need for real oversight by scrutinizing third parties,” said Benforado. “The Department of Labor’s resources have been decimated, but companies can claim there is no need to ask Congress for more money because they are already being audited.”

In an interview with Nina Mast, an economic analyst with the Economic Policy Institute, she highlighted the fact that the expansion of compliance audits occurs in conjunction with the diminished enforcement capacity of the Labor Department.

“This parallel enforcement structure between the federal government and private actors, at a time when we are seeing such widespread violations, undermines public accountability.” Mast continued, “Rather than relying on these third-party private organizations to hold the corporations that hired them accountable, we should really be expanding the enforcement authority of the DOL while increasing its resources and staffing capabilities.”

The privatization of enforcement through captured auditors provides companies further insulation from meaningful public accountability. As captured third-party audits fail to catch violations of child labor laws and the very structure of companies provides insulation from accountability, business interests are also engaged in a coordinated legislative effort to roll-back existing child labor restrictions as part of the broader movement to privatize public institutions and deregulate employment.

“What these bills are seeking to do is to legalize the violations that they’re already committing in these industries,” said Mast. “These proposals are really just attempts to codify the illegal behavior that they’re already committing and shield themselves from the eventual harms they impose because of their behavior.”

State-Level Efforts to Loosen Child Labor Restrictions

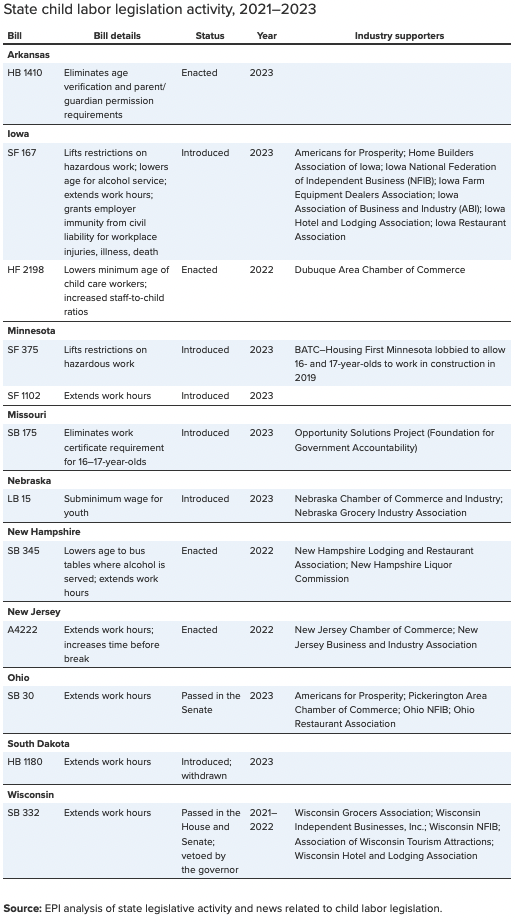

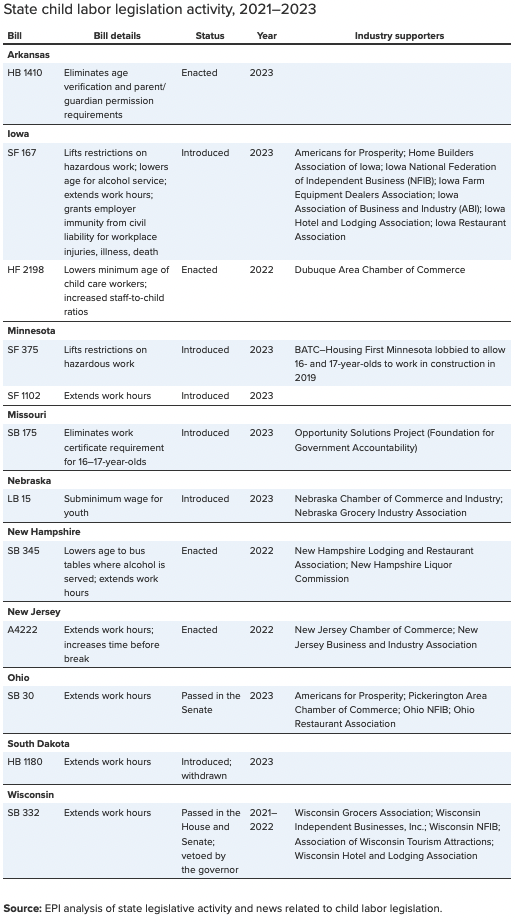

In 2023 alone, at least seven bills to undermine child labor protections were introduced and/or enacted in state legislatures across the country including Iowa, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, Ohio, South Dakota, and Arkansas. In the year prior, New Jersey and New Hampshire also enacted laws extending the permitted length of work hours for minors while providing some additional oversight and enforcement capacity of violations.

Many of the same states in which legislators and business interests are mobilizing to loosen restrictions are the same states in which the DOL continues to find egregious federal child labor violations. For example, fast-food franchisees with locations across these states and many others have recently been caught employing hundreds of children who were working excessive hours and performing prohibited tasks. In Chandler, Minnesota, a national food manufacturer illegally employed at least 11 children – nine of whom operated hazardous machinery – at its meatpacking and food processing facility.

The Economic Policy Institute recently released a report revealing the interests driving these state-level reform efforts. Mast, co-author of the report, described this widespread wave of legislation as “a coordinated, multi-industry effort to rollback standards that protect children from excessive or hazardous work led by a constellation of business industry lobbying groups as well as right wing think tanks as part of their broader agenda to deregulate employment, shrink the public sector, privatize our public institutions, and erode the social safety net.”

According to the report, the primary proponents mobilizing around this legislation are business-interest groups such as the National Federation of Independent Business, the Chamber of Commerce, and the National Restaurant Association. Other industry associations—like hotel, lodging, and tourism associations, grocery industry associations, home builders, and Americans for Prosperity—have also backed efforts to loosen restrictions through state legislation.

For Mast, these interest groups are pushing a “pro-business agenda that seeks to limit any guard rails that ensure the health and safety of workers as part of their the movement to erode the power of unions and relegate workers to low-wage, precarious work with few protections and little negotiating power.”

“The reason that they are interested in child labor is because this is a population that can be paid lower wages and is easier to exploit.” Mast continued, “At a time when we are seeing a tighter labor market and increased bargaining power among workers, instead of raising wages to recruit and retain a high-quality workforce, they would rather turn to youth who they can pay low wages, replace easily, and avoid the market pressures that force employers to pay higher wages.”

The coordinated effort to roll-back child labor protections is not constrained to simply extending the lawful amount of work hours for minors. This business-driven movement seeks to increase the scope of lawful child labor while also limiting employer liability for any injury or death that may occur as a result.

For example, the legislation first introduced in Iowa would have removed all civil liability from employers in the case of an injury or death of an employed minor. Because of a concerted, vocal opposition by advocates in the state, the provision eliminating liability entirely was removed. Nevertheless, the bill that passed still limits future liability for employers who are found to be in violation of the law.

The legislation in Iowa was not an isolated effort by business interests. A bill proposed in Indiana and passed by the state’s senate similarly would have eliminated all employer liability. That provision was also ultimately removed only after a strong response by child advocates.

Despite pushback, the movement to rollback child labor protections continues in 2024. In February, Republican lawmakers in Alabama introduced legislation hoping to further “eliminate barriers to employment” for 14- and 15-year-olds. The bill would eliminate safeguards that require children to receive permission from their parent or legal guardian, as well as an administrator, counselor, or teacher at the school they attend in order to work. The legislation mirrors a policy proposal written and advocated for by the conservative think tank Alabama Policy Institute in its 2024 policy agenda.

Similarly, in Wisconsin, the Republican controlled state assembly voted 62-34 along party lines, passing a bill that would eliminate work permit requirements for minors 16-years-old and under. For Republican lawmakers, the bill simply removes “bureaucracy” and “red tape,” providing children freedom to choose to work. For those opposed, like Rep. Katrina Shankland (D-Stevens Point), the legislation “takes away an important layer of transparency and accountability, ensuring that our employers are following all the laws related to ensuring our kids serve safety in the workplace.” Governor Tony Evers (D) intervened, vetoing the legislation.

The justification narratives deployed in support of legislative efforts often invoke similar notions of freedom of choice, consent, parental rights, and claims of improved child welfare. For example, in support of the Iowa legislation, Jessica Dunker, president and CEO of the Iowa Restaurant Association, argued that minors who want to work deserve the same freedom of choice as those who want to participate in typical after-school activities, framing the opportunity to work as “important” to child development.

However, in contradiction with the justifications, those same legislative efforts often remove requirements for parental consent, place children at greater risk of harm, and create the freedom to exploit minors rather than a freedom of choice. While children continue to be maimed and killed at work, instead of protecting minors, legislators and business interests are tirelessly working to legalize the unlawful behavior businesses are already committing, protect employers from liability, and ensure no accountability follows the predictable harms businesses inflict.

Not all states are capitulating to business interests. For example, on March 12, 2024, Oregon passed legislation increasing the fines for violating state child labor laws and empowering the state’s bureau of labor to pursue such violations.

The Path Forward: Children as the Future

Children need not remain alone and exploited in the American economy.

One underfunded, limited resourced federal agency discovered nearly 6,000 incidents of illegal child labor in 2023. Despite business interest groups’ frontal assault on existing child labor protections, the time to strengthen existing labor laws and their enforcement is now. The children who currently toil in the agricultural industry, whose employers enjoy exemptions from child labor regulations, should also not be forgotten.

Private markets and self-regulation will not correct the systemic mechanisms that produce child labor exploitation.

“The machine that we have set up with corporate law does exactly what it was designed to do. It is there to maximize shareholder profit regardless of harm.” Benforado continued, “If in fact you care as a society about more than profit maximization, you need to design a machine that has that output.”

For Benforado, the welfare of children should be the core concern of any system design, corporate or otherwise. He proposes replacing shareholder primacy and its relentless pursuit of profit maximization with a norm of child primacy and child prioritization in which the interests of children and our collective future is prioritized. According to Benforado, the law and our norms should reflect the fact that children are the canaries in the coal mines—“when we make them our focus, we all benefit.”

A corporate system of scapegoats and externalized costs rather than a system of oversight and accountability has emerged with child labor exploitation as a systemic feature, not a bug. The current status quo incentivizes a society in which children work overnight shifts and suffer severe chemical burns while cleaning skull splitters and brisket saws. Where such incentives exist and such outcomes become expected, a new system design is necessary.

On accountability, Laura Padin argued in an article, “If we really want to stop child labor abuses, responsibility must begin at the top of the supply chain.” She continued, “Big corporations have the power to ensure compliance with labor and employment laws among their labor contractors and prevent the exploitation of children within their supply chains.” For Padin, we “need laws that ensure large corporations with the power to eradicate child labor in their supply chains use that power.”

Accountability is best placed upon the entities that command power and exercise control in our dominant corporate systems. Whether by holding companies liable for violations within their supply chain or by establishing companies as joint employers in the fissured workplace, those with the power to define contract terms and define the race to the bottom must bear the burden of preventing the harms they produce. Freedom cannot be found in exploitation and profits prove hollow when earned at the cost of our future.

![[F]law School Episode 5: The Business of Boredom](https://theflaw.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/Reed_1-640x427.jpg)