From Individual Failing to Corporate Crisis

How the U.S. Identified the Cause of the Opioid Epidemic

Megan Corrigan

February 9, 2022

The Opioid Epidemic

February 9, 2022

America has been rocked by the opioid crisis. From New York to Massachusetts, from the heartland to the coasts, the opioid crisis has wreaked havoc. Consider the story of Journalist Masha Gessen. Gessen lives in New York and has been covering the opioid crisis for years. Their son, a college student, was prescribed opioids after attempting to climb a wall and breaking his ankle in 2019. Gessen’s son went back to college after the injury, and a few months later was placed on medical leave. He had not been attending classes, and Gessen did not know why. Shortly after coming home, Gessen’s daughter found her brother unresponsive. He had overdosed on OxyContin. Gessen wrote in the New Yorker last year that their son has since “got clean, relapsed, got clean again, relapsed again, flunked out of college, and destroyed his relationships with many of the people who love him, including me.” Even if he stays sober, his life is forever altered by his addiction. “He has told me that not an hour of his life passes when he doesn’t think about opioids,” wrote Gessen.1

Five hours away, in Cape Cod, Massachusetts, so many parents have been lost to the opioid crisis that schools have specialized counselors to deal with addiction-related trauma.2 PBS’s Frontline has a section of its website dedicated to “Heroin & Opioid Addiction, In Your Own Words.” Kyle from Fort Worth, Texas wrote in: “the people that use it ain’t bad people, it’s just that the drug itself is bad. It’ll grab you and never let you go.” Pam from New Smyrna Beach, Florida said: “We are not bad people trying to be good. We are sick people trying to get well.”3

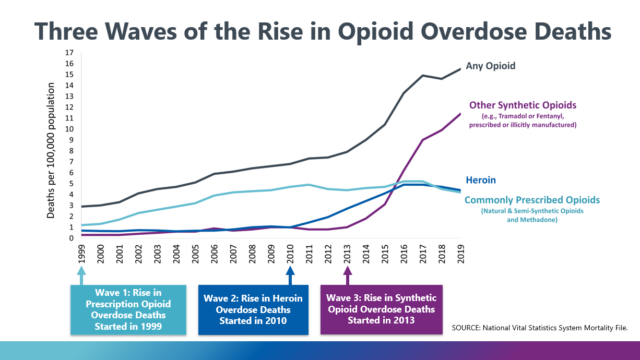

Opioid overdose deaths in the United States have increased sixfold since 1999.4 The Center for Disease Control and Prevention ties the massive increase to the proliferation of prescription opioids in the 1990s.5 Specifically, OxyContin, an opioid created by Purdue Pharmaceuticals, drove the large increase in opioid use. After Purdue’s aggressive marketing campaigns, use of opioids increased, and overdose deaths increased steadily in the first decade of the 21st century. Although Purdue changed OxyContin’s formula to make the drug harder to abuse in 2010,6 death rates increased sharply after the reformulation and numerous studies have tied it to an increase in illicit drug use. In one such study, one third of those who struggled with addiction to the original OxyContin replaced it with other drugs after it was reformulated. The vast majority moved to heroin.7

Graph from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/epidemic/index.html

There are more stories behind these numbers than any article could contain, and fatality statistics account for only the most extreme cases. Countless families have been impacted by the effects of addiction. In a 2018 Gallup Poll, 30% of Americans said that drug abuse was an issue in their families, and 72% said prescription pain killers were an issue in their communities.8

Their only motivation, and their only justification, was prescribed by the free-market bias in American law—the pursuit of profit.

As this crisis swept the country, it devastated National Book Award-winning parents in New York and kids on Cape Cod. Its impact was harshly felt across the heartland and on the coasts. But unlike previous drug crises, American attitudes towards opioid addictions have changed, and victims like Pam and Kyle are treated as such. Most Americans now believe that opioid abusers should be met with treatment, not incarceration.9 Many understand that the prescription drug crisis was brought about by Purdue Pharmaceuticals, a closely held corporation of the Sackler family. Their only motivation, and their only justification, was prescribed by the free-market bias in American law—the pursuit of profit.

Substance abuse has historically been criminalized in the United States, and previous drug epidemics have been attributed not to systemic problems, but to drug users’ dispositions. The crack cocaine crisis of the 1980s and 1990s serves as a salient example. The government’s policy response was to punish individuals, particularly Black and Latino drug users, rather than treat the crisis as a public health issue. The federal government passed laws that were not only tough on drug use, but were also specifically aimed at drugs more commonly used by people of color.10 Until recently, possession of crack cocaine, more commonly used by Black people, was punished 100 times more harshly than possession of powder cocaine, more commonly used by white people. Nowadays, it is still punished 18 times more harshly.11 These unequal sentences have been handed down for decades despite both drugs having essentially the same chemical makeup.

Comparing the crack and opioid epidemics side by side illuminates how the race of victims affects the government’s response. In effect, the dominant narrative of the crack epidemic painted those struggling with addiction as criminals rather than seeing them as victims in need of assistance. This outcome was a racialized choice by policymakers and media, as crack disproportionately harmed people of color. However, as the opioid epidemic swept through wealthier, whiter, and more educated communities, the narrative of drug addiction changed. The dominant story, as told by the media, policymakers, and popular culture, began to portray addiction as a disease. The blame shifted away from those using drugs and towards those profiting from them. Substance abusers came to be seen as victims and the corporate law mechanisms and greed that facilitated the epidemic were brought to light. By the mid-2010s, these factors brought an urgency to the crisis that led politicians to act and journalists to cover the story.12 But the opioid crisis was only able to reach so many because of the boundless and unregulated greed of those who produced it.

The proliferation of prescription opioids in America can be tied to one company and one family: Purdue Pharmaceuticals, owned by the Sackler family. The Sacklers made billions from the sales of Oxycontin, an opioid with powerful addictive properties that was marketed and sold to doctors as a safe drug.

Opioid treatments existed before Oxycontin, but doctors were aware of the addictive properties and prescribed them more cautiously. Purdue’s advertising claimed that OxyContin was not as addictive as other opioids, and that it would solve serious issues with pain across the country.13 Purdue’s marketing warned physicians of an “epidemic of pain,” and pitched OxyContin as the solution. The company told doctors that less than 1% of patients would become addicted to OxyContin and promoted the prescription of opioids for a long list of less serious conditions.14

Testimonials from the advertising materials showed happy and pain-free patients working, exercising, and enjoying life. Several of the patients featured in the promotional materials later became addicted to OxyContin. Stills taken from Milwaukee Journal Sentinel’s retrospective on Purdue’s original marketing campaign. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pkeQifzvSNE

In marketing to the public, Purdue paid for messages promoting the idea that ibuprofen and acetaminophen, better known as Advil and Tylenol, were unsafe, but opioids were “the gold standard of pain medication.”15 Purdue’s funded messages, designed to look independent from the company, said that these common household pain relievers had “life-threatening side effects” if taken in high doses.16

America’s preference for free markets effectively puts health in the hands of the highest bidder.

This type of pharmaceutical marketing is a uniquely American phenomenon. To start, the United States does not regulate drug prices—while other countries exert control on the market, the United States allows pharmaceutical companies to set their own prices. American law governing drug marketing is also highly permissive compared to other developed countries. This belief in the power of markets, when extended to healthcare, creates incentives for pharmaceutical companies to run massive marketing campaigns targeting both consumers and physicians. The United States is one of only two countries which allows direct-to-consumer drug advertising,17 but the majority of marketing spending promotes prescription drugs to the prescribers.18 America’s preference for free markets effectively puts health in the hands of the highest bidder. Despite being 4% of the world’s population, 42% of global prescription drug spending takes place in the United States.19 The permissive marketing structure, combined with the permissive pricing structure, creates the incentive and opportunity for bad actors to downplay the negative effects of a new prescription drug.

In this case, American law’s permission slip for profit-motivated corporate activity led directly to the opioid crisis. The FDA Scientist who evaluated OxyContin, Curtis Wright, wrote in his initial review that “[c]are should be taken to limit competitive promotion” of the drug, meaning that Purdue’s marketing could pose a danger to patients.20 Unfortunately, this recommendation was non-binding. American law has no such regulation of competitive drug marketing, and evidence suggests a direct link between the marketing of OxyContin and overdose rates today.21

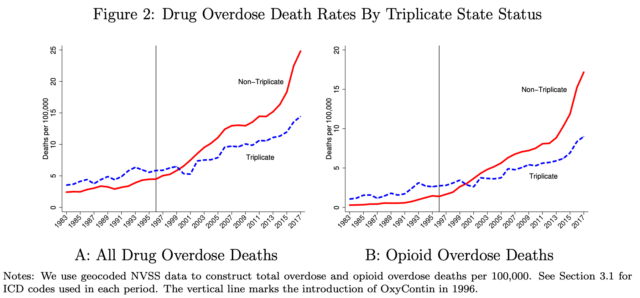

Evidence from the effects of prior attempts at opioid regulation suggests that it could have saved many lives. Prior to the introduction of OxyContin, some states had already suffered problems with prescription drug abuse. These states had introduced regulations which monitored prescriptions, requiring physicians to alert the state when potentially addictive opioids were dispensed. The programs were intended to make sure that patients did not receive multiple opioid prescriptions from multiple doctors. Today, many states have implemented similar programs in attempts to control the flow of opioids to individuals.22 When Purdue began pushing OxyContin, the company evaluated these regulated states as less fertile markets for their drug. The regulations, designed to curb opioid abuse, were seen as an obstacle to profits. Despite the company’s claims that the drug was safe, Purdue viewed attempts to control this controlled substance as interfering with their bottom line.

The regulations, designed to curb opioid abuse, were seen as an obstacle to profits. Despite the company’s claims that the drug was safe, Purdue viewed attempts to control this controlled substance as interfering with their bottom line.

As a result, the company invested less time and money in marketing to states with monitoring programs, opting to focus their efforts on the unregulated states instead. An internal report noted that, of physicians in states with these programs, “only a few would ever use the product, and for them it would be on a very infrequent basis.”23 Their internal report ultimately concluded that OxyContin “should only be positioned [marketed] to physicians in non-triplicate [regulated] states.”24 Since the opioid crisis has swept the entire country, regulated states have experienced significantly less growth in their overdose rate, a fact that remains true today.

Continuing effects of prescription regulations implemented in the 1990s. “Triplicate” states are states with monitoring regulations.

Massachusetts did not monitor opioid prescriptions prior to the introduction of OxyContin, and Purdue’s marketing team targeted doctors in Boston, southeastern Massachusetts, and Cape Cod. Some doctors received daily visits from sales representatives. When Purdue became aware that two doctors in Massachusetts were prescribing OxyContin inappropriately, they reported the incident to the board of the company, which included many members of the Sackler family. These doctors had made Purdue $823,000 in two years, and the company did not immediately report their excesses to licensing officials.25

Some corporate-caused crises get public relations benefits from complicated narratives. A faceless corporate entity pushing a product for the opaque master of shareholder profit through boring and confusing mechanisms is hard to hold accountable. However, that was not the case with OxyContin. A clear line can be drawn between specific actors and the corporation at issue, namely, the Sackler family, the owners of Purdue Pharmaceuticals who made over ten billion dollars from OxyContin and continued pushing the drug well after the crisis was in full swing.26

The Sacklers had a strong hand in the management of the company and pushed both the marketing of the drug in the 1990s and its continued growth even once its addictive properties were fully known to the company. The Sacklers were personally involved in the marketing plan to push opioids as safe starting in 1995 and continued to aggressively market opioids even while paying out settlements to families harmed by opioids. In 1997, the Sacklers considered marketing OxyContin as a non-controlled substance to increase prescriptions in some countries. The inventor of the drug objected, writing in an email to Richard Sackler, “I don’t believe we have a sufficiently strong case to argue that OxyContin has minimal or no abuse liability. . .oxycodone-containing products are still among the most abused opioids in the U.S.” Sackler ignored the report of risks and responded, “How substantially would it improve your sales?”27

The details of the Sackler’s relentless pursuit of profit over public health came to light in lawsuits, but the family’s notoriety arose from the work of activist artists who sought to draw attention to the opioid crisis and the family’s culpability. With their immense wealth, the Sacklers had engaged in philanthropy, financing museum and hospital wings with their names prominently displayed. Prominent museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and Harvard Art Museums, had wings or buildings named for the Sackler family. Artists affected by the opioid crisis used these endowments as an opportunity to draw attention to the Sackler’s profiteering off others’ suffering, demanding that their name be stricken from these cultural institutions. Nan Goldin, a photographer who struggles with opioid addiction, has led the protest movement to get the Sacklers’ names removed from museums and medical centers. Goldin hosted a “die-in” at the Guggenheim Museum to highlight the human cost of the Sacklers’ greed. She spread the message using hashtags like #ShameonSacklers. Goldin stated her aim in a 2018 editorial for ArtForum: “To get their ear we will target their philanthropy,” Goldin wrote. “They have washed their blood money through the halls of museums and universities around the world.”28 The Sacklers, in their family group chat, told each other that Goldin was “crazy” and “pulling a stunt,” but several recipients of Sackler philanthropy pulled the family‘s name from their buildings and institutes following her efforts.29

The Sacklers should have been held accountable sooner; it only took as long as it did for their role in the epidemic to come to light because of the interventions of very powerful people. In 2006, U.S. Attorneys working for the Department of Justice were prepared to prosecute Purdue Pharmaceuticals, along with their CEO, general counsel, and chief medical officer for the fraud perpetuated on the American public.41 According to the prosecution memo (a document prepared for the purpose of seeking approval from higher-ups to proceed with the indictment), executives at Purdue Pharmaceuticals were aware that the claims made in their 1990s marketing materials were false. The memo further alleges that the company was aware that OxyContin had addictive properties and that they had lied to physicians in their marketing materials to encourage them to write prescriptions for it freely. Privately, the Sacklers sought to blame those who became addicted to the drug for their struggles. In an email to a friend in 2001, Richard Sackler wrote, “[a]busers [of OxyContin] aren’t victims, they’re the victimizers.”42 In another email, he described this victim-blaming attitude as a public relations strategy. “We have to hammer on the abusers in every way possible. They are the culprits and the problem. They are reckless criminals.”43

But before that evidence could reach the public, Purdue’s powerful attorneys, including Rudy Giuliani, former mayor of New York City, met with top officials at President Bush’s justice department and the case was quashed. The attorneys were not permitted to proceed with the indictment and instead a guilty plea was negotiated for Purdue’s corporate entity. 15 years later, no Department of Justice official will own up to the decision to quash the case. The U.S. Attorney from Virginia who spearheaded the investigation faced political repercussions and was placed on a list of lawyers to be fired. One of the Justice officials involved in the decision to end the case was later indicted himself, for a separate incident of corruption.44

This backroom deal let Purdue off easy. Three executives pled to misdemeanors and served no time behind bars. Purdue’s corporation pled guilty and paid a $600 million dollar settlement, which amounted to just six months of the company’s OxyContin revenue, a fraction of the company’s earnings.45 The executives paid fines and the company continued using the marketing practices that led to the government investigation in the first place. The government celebrated the guilty plea as a win, and the more damning results of the investigation by the Department of Justice never saw the light of day—it was only in 2019 that the New York Times obtained a copy of the prosecution memo.46 Because influential people intervened, Purdue was let off the hook, and its executives were protected from the truth revealed by the investigation. The fraudulent behavior was not made public, and the lawsuit did not come close to the ultimate beneficiaries of that behavior: the Sacklers.

Because influential people intervened, Purdue was let off the hook, and its executives were protected from the truth revealed by the investigation.

Despite the company’s settlement with the Department of Justice in 2006, the Sacklers continued to make decisions based on profit rather than public health. In 2010, when executives reported a lower predicted growth rate for OxyContin sales than the Sacklers wanted, Richard Sackler responded, “I’m disappointed and don’t agree with you. This is a matter that the Board will have to take up and give you a settled direction.47 Richard and Mortimer Sackler discussed the issue and encouraged management to push the drug to more prescribers. Sales declined anyway. According to Purdue’s internal studies, this was due to a decrease in medically unnecessary prescriptions.48 The company was aware of problematic prescribers who doled out more than recommended amounts of OxyContin, and the decrease in doctors willing to do so caused much of the decline. The Sacklers were made aware of these findings by December 1, 2010.49 After expressing concern over the declining sales, regardless of the public health reasons behind them, Mortimer Sackler recommended searching for a new CEO and replacing the head of sales and marketing.50

After decades of pain and effort, Purdue Pharmaceuticals declared bankruptcy in the face of thousands of lawsuits. In 2021, Purdue Pharmaceuticals and the Sacklers reached a proposed settlement with the federal government and several states for massive sums of money, including over 4.5 billion dollars from the Sacklers’ family wealth.51 That settlement was thrown out by a federal judge in December because it shielded the Sackler family from future opioid litigation and, as of this writing, the parties have yet to reach an agreement.

Purdue’s role in and response to the addiction crisis they caused offers several lessons and priorities for change. Purdue didn’t change course when presented with evidence the addictive nature of OxyContin. Instead, they fought to keep aggressively marketing it despite its known risks. Drug marketing should be tightly regulated in America, as it is internationally. No doctor should get visits every day from a pharmaceutical representative, as some did in Massachusetts. Further, the profit motive in healthcare must be carefully studied and hemmed in where it leads to excesses. Drug pricing may not need to be regulated exactly as it is abroad, as some argue that pharmaceutical prices in the United States may be important to incentivizing the development of new drugs.52 However, the current regulatory framework treats healthcare companies far too similarly to companies selling consumer goods. Healthcare has never been a real “market,” as any American turned away from a doctor’s office for lack of insurance coverage can tell you. The incentives here are not balanced between a seller and customer, who can walk away or shop elsewhere, in the classic economic model. Rather, decisions are made between a patient with limited information and her doctor, her insurance company, her pharmacist, her government, pharmaceutical companies, and the shareholders of those pharmaceutical companies. And the stakes are life and death. America has previously decided that some things are too important to commodify and has accordingly treated them as public goods, regulated separately from the market. Healthcare should be added to that list.

America has previously decided that some things are too important to commodify and has accordingly treated them as public goods, regulated separately from the market. Healthcare should be added to that list.

Furthermore, policymakers shouldn’t moralize when planning the path forward for those in the grips of the opioid crisis. Two successful harm-reduction strategies—medication-assisted treatment and supervised injection sites—face opposition because of concerns about condoning drug use. Despite being highly successful at helping those with addiction get back to their normal lives, medication-assisted treatment programs for addiction are hard to access because policies are designed to keep users away from any kind of drug. Supervised injection sites, while proven to reduce deaths, have yet to be established in the United States because of similar concerns about enabling drug use.53 Finally, profit motives have followed the crisis even into treatment for addiction. At one point, Kathe Sackler suggested getting into the business of Suboxone, a drug that treats addiction, to continue profiting off those drawn into Oxycontin’s vicious cycle.54

With so many lives lost and altered, it is hard to know what justice would look like in the wake of the pain caused by Purdue. Even if the Sacklers were incarcerated and forced to return all of the billions of dollars they earned, it would not cure addiction for those suffering from it or undo the deaths from overdoses. However, we could repair the incentives for pharmaceutical companies and others to prioritize human health over profit before another pharmaceutical company starts the cycle anew.

Commodifying Culture

How much is a museum willing to sacrifice for the soul of a nation?

McDonalds Food Safety Disparities

Business of College Admissions

How Private Tutors Profit Off Asian Immigrant Anxieties.

Social Media Harms

In Pursuit of Accountability for Social Media’s Mental Health Impacts

Transgender Justice

How Profit-Driven Media Outlets Empowered the Anti-Trans Movement

Protest Surveillance Technology

Protest Movements and the Corporate Surveillers Profiting Off Fear

Public Interest Washing

How public interest messaging paints a misleading picture of HLS

Capturing Nonprofits

The Corporatization of Drag

“Drag used to be ‘fuck the system’ and now drag is the system.”