Similarly, DPH inspectors cited Prospect Medical’s hospitals in Connecticut for rusty operating room equipment, furniture that was being held together with tape and couldn’t be cleaned, and other deteriorating facilities.

One of the CEOs of Prospect, Sam Lee, was living in grander facilities: an $8.5 million Beverly Hills home, an Aspen estate assessed at $16.5 million, and a 10,000-square-foot, $3.5 million home in Santa Monica.

In November 2023, Rockville General and Manchester Memorial Hospitals owed $5.9 million to local vendors and $5.18 million to physicians for uncompensated care. In a recent lawsuit filed by Yale New Haven Hospital against Prospect, the complaint alleged that Waterbury Hospital had not paid its vendors over $40 million owed.

Some unpaid vendors claimed they would have to declare bankruptcy due to the nonpayment. Other vendors, like the elevator supplier at Waterbury and Manchester hospitals, refused to maintain the elevators without payment. As a result, the complaint alleges that hospital staff has been forced to carry patients up and down stairs.

“The cafeteria is now self-serve, consisting of vending machines. Gone is the fresh food and the employees who served it. Even the friendly cashier was replaced by a kiosk.”

According to Batt, this picture of disinvestment “contradicts what private equity says all the time” about their willingness to invest and improve in hospitals.

Glen Maloney has been a mechanic within the engineering department of Rockville General Hospital since 2001 and was the president of local Manchester union. Testifying at the OHS public hearing, he noted that wings of the Rockville General Hospital remained closed, with equipment removed and employees displaced. Even the gift shop closed, since there were no longer visitors.

“The cafeteria is now self-serve, consisting of vending machines. Gone is the fresh food and the employees who served it. Even the friendly cashier was replaced by a kiosk.” Without the people that made the hospital a community hub, Maloney pondered that with so many services cut, “perhaps RGH is no longer considered a hospital.”

Staffing: While staffing cuts are a normal part of hospital cost containment strategies, private equity-backed hospitals take it to dangerous extremes. Research indicates that hospitals acquired by private equity funds go on to have staffing reductions.

Connecticut DPH reports across all three Prospect hospitals cited them for inadequate staffing levels, leading to high patient to staff ratios. Ellis noted that the Rockville General Hospital “started off with roughly 100 nurses, and now there is maybe about 20 left.”

Reductions in staffing, combined with deteriorating facilities and fewer resources to care for patients, can also make it more difficult to retain well-trained staff. Allegations of patient abuse emerged after unannounced visits by the Connecticut Department of Public Health to Waterbury and Manchester Memorial Hospital in 2023.

At Manchester Memorial, internal staff communications in 2023 detailed disturbing claims against a nurse “having intimate relations with patients both while admitted at the hospital and after discharge.” According to the DPH inspection report, the nurse was accused of “kissing and touching” a patient’s private area while the individual was being treated for paranoia and anxiety.

Text messages obtained as part of the investigation revealed the nurse sent money to the patient. Despite hospital leadership receiving reports of the alleged abuse, the nurse remained on duty for nearly three months in violation of hospital policy.

At Waterbury Hospital, another DPH report contains allegations that a hospital employee verbally abused patients and “roughly handled” them. The employee continued to work with patients for months after reports of the mistreatment surfaced.

DPH inspection reports across the three hospitals also show a pattern of staff inappropriately using restraining devices on patients when less restrictive means of care was required.

Image taken by Frederic Köberl and provided by Unsplash under a creative commons license.

Breaking Community Ties

For hospitals like Manchester Memorial and Rockville General Hospital, where both facilities are over 100 years old and have deep ties with the surrounding community, these changes are devastating blows. Similarly, Waterbury Hospital was founded from donations given in church collection baskets in the nineteenth century and is the town’s largest employer. When private equity disinvests from care and devalues essential labor, the impact ripples through communities.

“The community spirit once thriving throughout its hallways has diminished. It struggles to survive as its resources and services are removed one by one.”

In 2023, nearly a quarter of health care companies that filed for bankruptcy were owned by private equity funds. Rural communities are more vulnerable to reductions in health care services, and a closure or service disruption may mean that a community no longer has access to basic services.

Commenting on Rockville General’s decline, Glen Maloney noted “the community spirit once thriving throughout its hallways has diminished. It struggles to survive as its resources and services are removed one by one.”

The Narrative of Private Equity: Value Creation and Transformation

Health care is an attractive sector for private equity firms—health care needs are expected to increase with an aging population and there is a stable flow of income through government insurance programs like Medicare. As a result, private equity buyouts account for nearly half of all mergers in the health care sector.

But what justifies the intensity of private equity activity in health care? Recent analysis by finance economists have shown that the overall performance of private equity funds has been declining, and the median buyout has matched the performance of the stock market since 2006. Private equity isn’t offering better returns than more regulated forms of investment.

Powerful narratives from private equity firms and seemingly endless private equity funds help bolster claims of the value and legitimacy private equity practices.

Three pillars—investment, patient care, and efficiency—form the foundation of the value that PE firms allege to provide in the health care context. These promises can look like a panacea in health care systems dealing with high costs and heavy regulatory burdens. Hospitals like Rockville and Manchester, for example, struggled financially even before the deal with Prospect.

Investment: Private equity firms will often make promises to invest in capital improvements to improve facilities and expand services. When Prospect Medical purchased two hospitals in Rhode Island, they committed to investing $50 million in long-term contributions within four years. An investigation by ProPublica uncovered that Prospect did not honor this contractual commitment.

Prospect Medical also actively disinvested from its hospitals, engaging in a dividend recapitalization that paid owners $457 million. This happened only four years after assuring regulators they would not.

Patient Care: Batt explained that private equity firms will “say they’re going to help improve processes and patient care. But there’s no evidence to that effect.”

In a statement written by a crisis PR firm to ProPublica, Leornard Green and Prospect asserted “Prospect Medical Holdings is a healthcare system that provides compassionate, accessible, quality healthcare and physician services.”

Quality ratings by the federal government scored Prospect hospitals with the lowest possible value of one or two stars—a rating only given to the bottom 17% of hospitals.

Efficiency: Private equity firms claim they bring management expertise that streamlines operations and lets providers spend more time on patient care while private equity-backed ownership takes care of administrative responsibilities and “burdensome paperwork.”

In a confidential memorandum obtained by ProPublica for prospective purchasers of Prospect Medical in 2015, Leonard Green promoted the hospitals’ efficiency—including a “cost-effective care” model, “flex” management of hospital staffing, high-profit mental health program, and low-cost sources for medical supplies.

Meanwhile, the number of beds at Rockville General Hospital’s surgical and intensive care units decreased by over 50% while state officials cited Prospect-owned hospitals in Connecticut for inadequate staffing, deteriorating equipment, and inappropriate use of restraints for mental health patients.

This portrayal is critical to maintaining the legitimacy of private equity activities, since they are effectively shielded from public scrutiny and largely outside the scope of regulatory bodies. The secrecy surrounding private equity makes this narrative challenging to disrupt.

But the story private equity firms weave tells a story at odds with the realities of private equity-backed health care facilities like Waterbury Hospital. The limited data available suggests private equity activity leads to worse access, lower quality of care, higher prices, and poorer conditions for health care providers.

The Business Model of Private Equity

The structure of private equity transactions starts to show the cracks at the foundation of private equity’s narrative, one that demonstrates how private equity funds are constructed to benefit the private equity firm above all by shielding them from risk, liability, and public scrutiny. Private equity is structured to redistribute wealth from working class communities to the private equity firm itself, relying on minimal regulatory oversight to maintain secrecy.

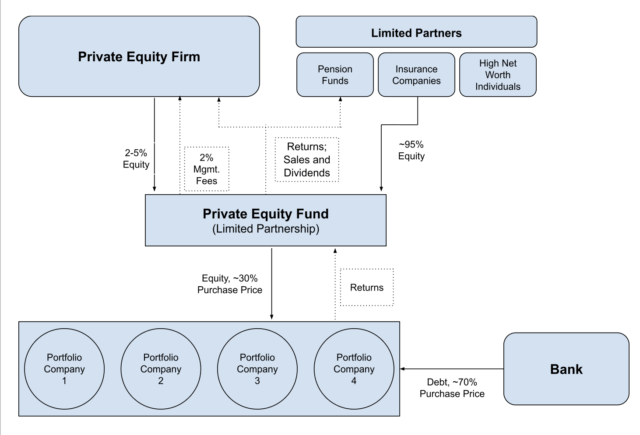

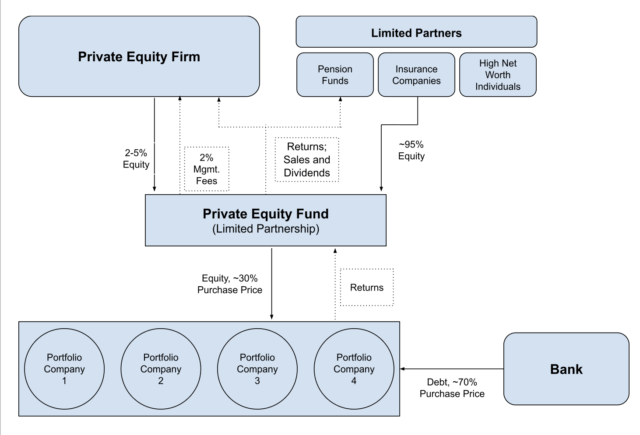

Private equity activity begins when a private equity firm like Leonard Green raises funds from outside investors to aggregate into a large pool of money, known as a private equity fund. Not everyone, however, is not allowed to participate. The federal government restricts participation in private equity funds to certain types of wealthy investors. This makes the returns private equity purports to provide generally inaccessible to the average American.

The structure of private equity transactions starts to show the cracks at the foundation of private equity’s narrative, one that demonstrates how private equity funds are constructed to benefit the private equity firm above all by shielding them from risk, liability, and public scrutiny.

The government is not the only restriction limiting participation. Each fund has a minimum investment amount that can range anywhere from $100,000 to $10 million. Private equity funds raised an average of $1 billion in 2021, but now almost a third of all private equity deals were mega-funds valued above $5 billion.

A private equity fund is managed by the private equity firm in a legal structure known as a limited partnership. This allows private equity firms to have full control over the fund as a “general partner,” while the other entities that contribute to the fund have little to no management involvement. They are known as “limited partners.”

This legal set up allows private equity funds to be black box for limited partners: once a limited partner decides to put money into a fund, they generally cannot remove their contribution or realize returns for a period of ten years. Limited partners are only given minimal information about what companies the fund is purchasing or the financial status of the fund.

Graphic adapted and simplified from private equity organizational chart found at source.

Limited partners provide approximately 95% of the money in an investment fund, while the private equity firm itself only contributes the remaining 2-5% of the total fund. Private equity firms also charge a 2% annual management fee of the capital in the fund, a figure that ranges from tens to hundreds of millions of dollars. Over the lifespan of a private equity fund, this equates to 20% of the entire fund taken as a management fee by the private equity firm.

Regardless of whether the fund performs well, the private equity firm always makes a return. This incentivizes reckless behavior to the point where it can be more profitable for a private equity firm if the portfolio company goes bankrupt.

Private equity firms manage an average of 4.5 of these funds at any given time. This structure—where the private equity firm provides a negligible contribution and charges an equivalent annual management fee—essentially absolves PE firms of any risk for a fund’s performance. Regardless of whether the fund performs well, the private equity firm always makes a return. This incentivizes reckless behavior to the point where it can be more profitable for a private equity firm if the portfolio company goes bankrupt.

How Private Equity Plunders Our Hospitals

The central strategy of private equity firms in health care is the leveraged buy-out. Once the private equity firm has amassed a large enough fund, the firm will use the fund to buy companies to build out a portfolio of businesses.

In a leveraged buyout, a private equity fund will first buy a hospital. The private equity firm will use borrowed funds to finance about 70% of the purchase, using the hospital’s assets as collateral for the debt used to buy the company. The acquired hospital then becomes responsible for generating revenue to repay the debt—not the private fund that purchased the company or the private equity firm that managed the acquisition.

When the private equity fund owns the portfolio company, the PE firm seeks to extract as much value as possible before offloading the company within three to seven years. In the Connecticut case, Leonard Green purchased the hospital chain Prospect Medical, who then purchased the three Connecticut hospitals. Leonard Green and other private equity firms maintain control of their purchases by appointing new leadership to implement their goals.

There are a few main strategies private equity firms use to financially engineer guaranteed returns.

Dividend Recapitalization: Private equity firms will often engage in dividend recapitalization to get quick cash when a portfolio company is not generating enough revenue. In 2018, Prospect Medical took on additional debt worth $1.1 billion. The hospitals’ assets were used as collateral, similar to the initial purchase. The proceeds of that debt were used to pay Leonard Green $457 million cash as profit.

Prospect Medical and its hospitals were then responsible for generating enough revenue to pay off the debt and the interest—but the initial debt was taken out because the hospitals weren’t generating enough revenue. As a result, hospitals had less cash available to pay staff, improve patient care, or maintain facilities, leaving them vulnerable to shifts in the market or unable to meet their debt obligations.

Rhode Island AG Peter Neronha wrote of the dividend recapitalization “When it was paid, the $457 million represented approximately 60 days of PMH’s operating expenses. And it came at a time when PMH had only 1 day’s worth of cash on hand.”

Sale Leasebacks: Prospect was only able to pay off the debt from the dividend recapitalization with a sale leaseback, another method private equity firms use to extract even more value. The tactic entails selling a hospital’s real estate to a third party. Where the hospital previously owned the land or other assets, it must now lease the same property from the new owner. The profit is then funneled to the private equity owners.

“A for-profit hospital would never sell its property because they need the property as collateral to take out loans to get loans for construction, or for a facility maintenance or technology. They need that for long-term sustainability” said Batt, distinguishing private equity activities from other types of hospital owners.

Hospital-Specific Tactics: Private equity firms will also use other hospital specific strategies to raise revenue and decrease costs.

In addition to raising prices, hospital systems will engage in surprise billing, which occurs when patients are billed for services during an in-network visit that are unexpectedly and unavoidably out-of-network—such as being assigned an out-of-network anesthesiologist during surgery. Hospital systems will also “upcode,” which occurs when hospitals bill insurance for a more expensive service than was actually provided to the patient.

Destabilizing Care for Communities

After a private equity firm leverages mountains of debt against a hospital, it’s nearly impossible for hospitals to meet their debt obligations while serving patients. The debt layered onto community hospitals have destabilizing effects that result in lost access to care, disruption in treatment, and lower quality services.

During the second year of Prospect’s ownership, Rockville and Manchester hospitals generated a combined net income of $2.8 million in 2017. The downward trend began the following year, with a net loss of $3.1 million. By 2021, after extracting profit from the three hospitals through a dividend recapitalization and a sale leaseback, Leonard Green quietly sold its stake in Prospect Medical in 2021—avoiding any financial responsibility while leaving Prospect Medical, patients, and communities in a sinking ship. By 2023, Rockville and Manchester hospitals had a net loss of $49.8 million.

By 2024, the hospitals were on the brink of closure. Prospect owed $67 million in state taxes, over $20 million in local personal and property taxes, and tens of millions to vendors. Federal liens filed against Prospect alleged that the health system failed to pay into the pension plan for employees, as required by state law. The situation sparked a Senate investigation that found Leonard Green had used the Connecticut hospitals as their “personal piggy banks.”

Prospect signed an agreement with another hospital chain, Yale New Haven Hospital System, to acquire the three Connecticut hospitals. This deal fell apart once Prospect Medical filed for bankruptcy in early 2025 and is now being litigated.

“There is a fundamental tension here between the short-term gains that these firms need with the long-term hope of what these health systems are supposed to provide,”

Private equity firms, aware that states have incentives to keep essential hospitals operational, rely on subsidies from state government and taxpayers to fund their debt. Prospect chose not to pay state or local taxes, eventually leading to a settlement agreement that Prospect still refused to pay. Yale New Haven Hospital even requested that the state subsidize their purchase of the three hospitals, which the state denied.

In the midst of all of this, patients and employees existed in limbo where it was unclear how their hospitals would survive, who would own them, or if resources would be available to treat patients and pay employees. “There is a fundamental tension here between the short-term gains that these firms need with the long-term hope of what these health systems are supposed to provide,” said Joseph Bruch.

What was clear, however, was that Leonard Green and Prospect Medical’s involvement in Connecticut’s health care systems did not appear to be providing the value they promised to taxpayers, vendors, patients, employees, or communities. Rather, private equity’s maneuvers actively harmed those it claimed to support by plundering Connecticut’s community health care.

The Misdirection of Private Equity

The intensification of private equity activity in health care only amplifies the negative effects. PE activity currently accounts for over half of all mergers in healthcare. As private equity buys more and more health care facilities through leveraged buyouts, more hospitals are loaded with debt they can’t pay off and are vulnerable to permanent closures as a result.

While consolidation is not limited to private equity, the speed at which PE firms consolidate and extract assets from health care facilities is unique.

But unlike other large hospital systems or insurance companies that purchase health care entities, the ownership and management of private equity firms are not subject to substantive government oversight. Because the path of ownership can be obscured, the failure of a safety net hospital like Rockville General Hospital can simply look like the result of financial struggles that existed before private equity acquired it.

“Private equity goes after the companies that have really solid fundamentals but are undervalued,” said Rosemay Batt. “If you take the Steward case, they were struggling hospitals, but they were in solid communities that had really good hospitals and good staff.” The foundation of all these hospitals was sound, and Batt noted that many hospitals acquired in the 2010s were struggling financially because they were coming out of the Great Recession. That solid foundation, however, crumbles once private equity arrives.

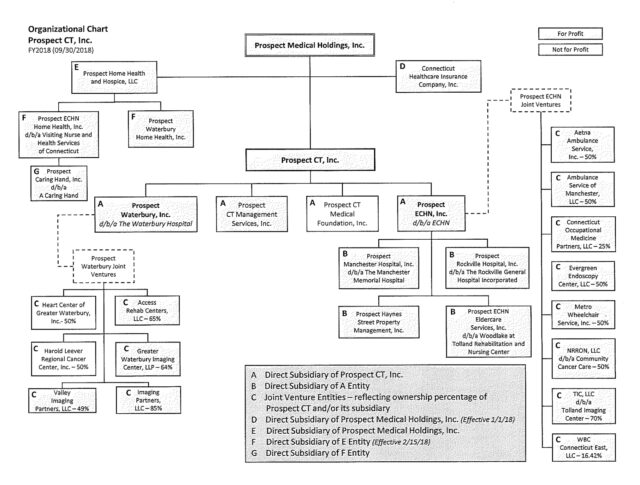

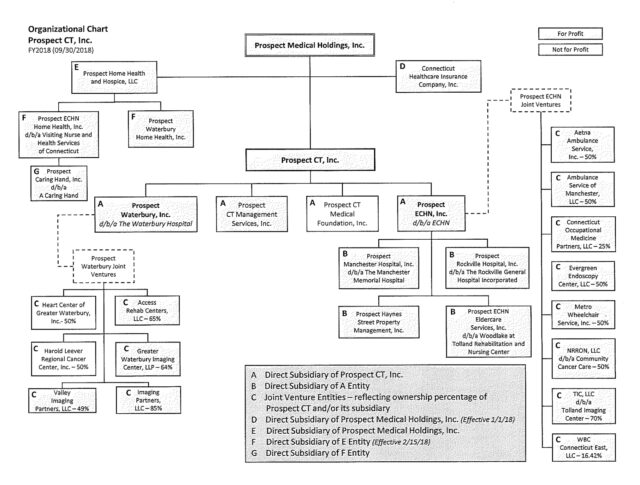

It can also look like the blame rests entirely on the mismanagement from the hospital chain owner, despite the private equity firm’s ultimate ownership and control. Required financial filings submitted to the state shows a complex organizational chart that only includes Prospect, not its private equity owner Leonard Green.

Public record provided by Connecticut’s Office of Health Strategy under the Hospital Reporting.

It is easy to single out individual facilities as individual failures rather than being the product of the structure of private equity ownership and management. While economic conditions or poor management can contribute, the real culprits are the strategies private equity firms use in dangerous and excessive ways—from leveraged buyouts, dividend recapitalization, and sale leasebacks.

How Private is Private Equity?

The “private” distinction is the foundation of private equity’s ability to control the narrative without outside interference from the government and investors. Being private gives private equity firms legal permission to keep financial information hidden. Being private justifies keeping investors and the public in the dark about their activities. But pensions funds and endowments invest funds on behalf of millions of workers and students, just as public companies do.

The secrecy that PE firms purport to require to protect trade secrets and maximize efficiency for limited partners also helps avoid disclosure laws that would cause the public, the government, and investors to question the value private equity provides.

It is easy to single out individual facilities as individual failures rather than being the product of the structure of private equity ownership and management. While economic conditions or poor management can contribute, the real culprits are the strategies private equity firms use in dangerous and excessive ways—from leveraged buyouts, dividend recapitalization, and sale leasebacks.

Health care is unique for private equity investment because patients have constrained choices—there are often few options but to be treated at a local community hospital, especially for disabled, low-income or other vulnerable patients. Health care is essential and unavoidable.

But when private equity firms are able to layer hospitals with debt, extract cash from a hospital with a dividend recapitalization, or redistribute a hospital’s assets with a sale leaseback, private equity activity transforms hospitals into financial products that can be sold and traded to accumulate capital. Suddenly, a complex financial maneuver that destabilizes patient care and reduces the financial health of essential medical facilities can be characterized by private equity firms as creating “value” and “gains.”

“Health care firms have increasingly started to mirror the logics of the financial firms. So you don’t just have hospitals delivering care to patients,” stated Bruch. “Here you have hospitals with venture capital arms. You have hospitals that now offer financial products in the form of medical credit cards to patients. You have hospitals that increasingly reliant on their investment portfolios.”

Through this process, the high levels of debt and reduced access and quality of care threaten to become normalized while the damage is absorbed by patients and employees at places like Rockville General Hospital. The private equity model redirects pressure, shifting insecurity to workers, patients, and communities, while simultaneously obscuring its actions from public scrutiny. At its core, putting hospitals into debt is the main reason private equity offers any return to investors at all.

Suddenly, a complex financial maneuver that destabilizes patient care and reduces the financial health of essential medical facilities can be characterized by private equity firms as creating “value” and “gains.”

But the situation is not inevitable. “The law allows it,” stated Batt. “This idea that it’s inevitable, I think assumes that people are totally passive.” Connecticut legislators are currently considering bills to help curb private equity’s influence in health care. “There are always creative alternatives. The state can create alternatives. The state can create legislation, localities can create alternatives.”

Equity for Whom?

In the end, for whom does private equity activity create value? Private equity achieves efficiency in creating returns for private equity firms with minimal risk and oversight. Private equity invests in its own financial gain by leveraging debt to extract the value of critical health care facilities. Private equity diminishes patient care quality in favor of financial engineering that lines their pockets and harms communities. “All I hear from them is about cost savings to them. It sounds more to be profits over patients,” said Christen Ellis.

“They have dismantled our Rockville family, patients, doctors, staff and community, leaving us fractured.”

![[F]law School Episode 9: Profits Over Patients](https://theflaw.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/danie-franco-CeZypKDceQc-unsplash-scaled-e1735518825718-640x427.jpg)