Homeless in America: 40 Years of Crisis

The Role of Corporate Interests in “Contemporary Homelessness”

Chris Lester

February 23, 2024

Homelessness has become an accepted part of American life. For those of us living in densely populated cities, it’s a given that you will likely encounter someone experiencing homelessness on your walk to the store, on your way to work, or even outside your building. For those in suburbs or rural areas, homelessness may be less visible but is likely no less pervasive. As a society, it seems that we have admitted that unsheltered individuals and families are just a part of life in the richest country in the world.

This is not to say we haven’t made efforts to address this crisis. Nearly every candidate running for office in a major city or on the national stage has made at least some mention of the need to address homelessness, though their plans to do so can vary dramatically. From initiating campaigns to engage with landlords to encourage them to accept tenants with federal rent subsidies to complete criminalization of homelessness, elected officials have proposed plans that demonstrate a political will to get people off the streets (even if the alternative is to funnel them into jails). Unlike many of our current social and political issues, there seems to be agreement that efforts should be made to reduce or attempt to end homelessness. However, the issue remains more prevalent than ever.

While there are no doubt innumerable factors in our current society that contribute to the number of homeless individuals, including rising cost of living, wage stagnation, and the lingering effects of the Covid-19 pandemic, this crisis is not a new phenomenon and should not be treated as such. To make genuine efforts to address homelessness in the United States, we must understand its current status and our existing responses as well as how and why we got to this point. This article will examine these factors with an eye towards the influence of corporate interests on governmental policies at the time our modern homelessness crisis began.

The United States Department of Housing and Urban Development’s (HUD) 2022 Annual Homeless Assessment Report found that 582,462 people were experiencing homelessness on a single night in January 2022. This was a 0.3% increase compared to the 2020 count, though this figure is likely underinclusive as the HUD’s estimate is only representative of a single night and may exclude those not in the shelter system or easily found. In an effort to address this crisis, hundreds of millions of dollars of major city’s annual budgets are allocated to homeless services: $2.2 billion forecasted to NYCs Department of Homeless Services in 2023, $609.7 million to the Los Angeles County Homeless Initiative in 2023, $111.4 million to Seattle’s Human Services Department in 2023 for the purpose of addressing homelessness. This money goes to providing temporary emergency shelters, funding employment and job training programs, and offering other services essential to providing aid to homeless individuals. Despite these investments, homelessness remains a pervasive problem in many major cities. These figures and their effects indicate a well-known fact: our responses to the homelessness crisis aren’t working.

When beginning my research into this topic, I intended to examine how the funds of homeless service departments were allocated to understand why such large investments were failing to substantially impact the number of homeless individuals. My initial theory was that elements of the homeless services system had been captured by some corporate interests, leading to upcharges on contracts for supplies and services necessary to run shelters and other essential programs. However, as I continued my research and spoke to those with experience working within and around shelter systems, it became apparent that the ways in which these departments used their budgets was a less important factor than why these departments were receiving this funding to begin with. Understanding the origins of and history behind this seemingly outsized funding is essential to determining how we got to this point.

“People see the money and think the money should naturally reduce homelessness, and the sector is housing more people than ever before, but they cannot keep up because homelessness is a symptom, not a cause.”

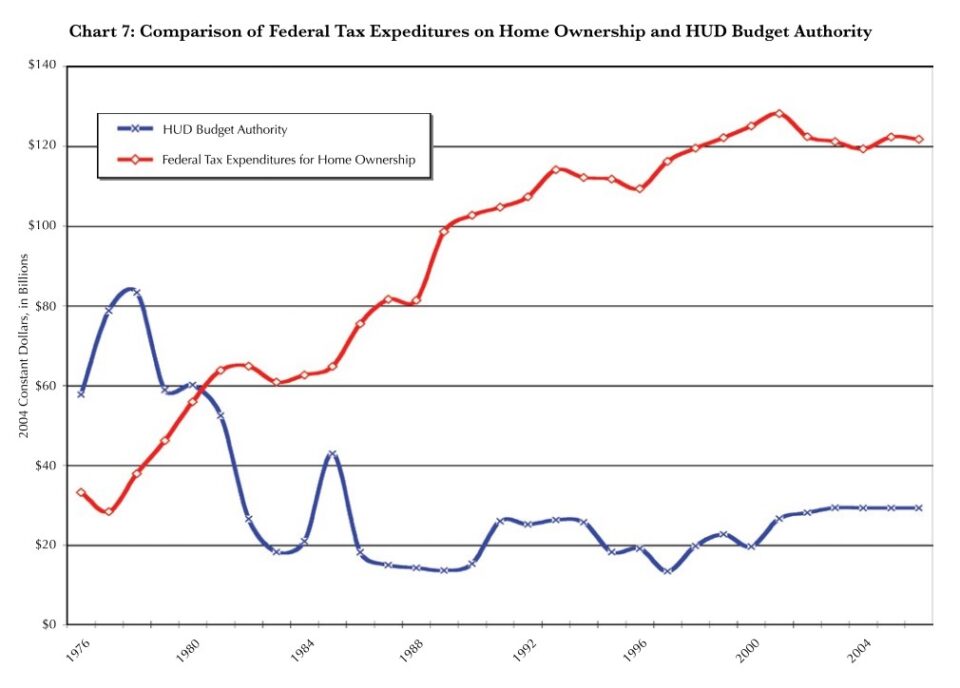

The effect of this history on the current state of homelessness was first brought to my attention in my interview with Mark Hovath, the founder of Invisible People, a nonprofit “dedicated to educating the public about homelessness through innovative storytelling, news and advocacy.” Mark launched Invisible People in 2008 after the financial crisis because of his belief in the importance of narrative change. During our conversation, we discussed the perceptions around the amount of funds being allocated to homeless services and his response to those that question their lack of effectiveness. “People see the money and think the money should naturally reduce homelessness, and the sector is housing more people than ever before, but they cannot keep up because homelessness is a symptom, not a cause.” This concept of homelessness as a symptom of other social and political factors was a common theme throughout the interview, with Mark seeming to focus less on the practices of those in homeless services departments and more on why they have to operate in the ways that they do. According to Mark, many of the factors that helped to cause our current homelessness crisis began in the 1980s with the “Reagan revolution” and the new housing priorities and policies it introduced.